A Visit With Miklós Rózsa | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Jeffrey Dane, New York, NY USA | Date: 16.09.2011 |

Miklos Rozsa, at left, in his living room, talking with author Tony

Thomas.

According to Juliet Rozsa, her father is in his favorite chair. Miklos Rozsa, at left, in his living room, talking with author Tony

Thomas.

According to Juliet Rozsa, her father is in his favorite chair.I recently saw personal photos taken in the home of Miklós Rózsa in Los Angeles, California in 1985. These snapshots stirred within me the marvelous memories of my own visits there with Dr. Rózsa on two occasions three years later. The color photos herewith presented are from the personal collection of Mr. Scott Dawes of Austin, Texas USA, and appear here with his permission and through his kindness and courtesy. The numerous times on which I had the pleasure, the honor, of spending time with composer Miklós Rózsa represent significant moments for me. I’d have been a different person if I hadn’t come to know Leonard Bernstein during my student days, and then to study his work. With Rózsa, however, I knew his music for years before I finally got the opportunity to meet the man himself in 1972, for the first time – thirteen years late but certainly none the worse for it. I saw and spent time with him frequently throughout the ensuing years, but I relate here this meeting here because it was the last time I saw him. And I’m glad it was at his home. | More in 70mm reading: Remembering Miklós Rózsa Remembering Dimitri Tiomkin Internet link: The Miklos Rszsa Society Miklós Rózsa's 70mm Film Soundtracks El Cid King of Kings Ben-Hur |

Another view of the living room. The chair will look familiar to some Rozsa aficionados:

it’s the one in which the composer is sitting in the photo used on the cover

of the RCA Stereo

LP recording LSC-2802, “Rozsa Conducts Rozsa,” containing the Theme,

Variations & Finale,

Three Hungarian Sketches, Concert Overture, and the Notturno Ungherese

(Hungarian Nocturne). Another view of the living room. The chair will look familiar to some Rozsa aficionados:

it’s the one in which the composer is sitting in the photo used on the cover

of the RCA Stereo

LP recording LSC-2802, “Rozsa Conducts Rozsa,” containing the Theme,

Variations & Finale,

Three Hungarian Sketches, Concert Overture, and the Notturno Ungherese

(Hungarian Nocturne).In 1988 I traveled to California for the rehearsals and West Coast USA premiére in Los Angeles of Rózsa’s Viola Concerto. I was there for eight days (for a New Yorker it’s strange to walk about outdoors in shirtsleeves in January), and twice during that week Dr. Rózsa invited me to his home. Over the years countless people attended his concerts and many had the pleasure of personally making his acquaintance – but only the select have been privileged to enter the sanctuary of Rózsa’s magnificent home. I’m very thankful I’m one of them. It would be understatement epitomized to say it was not the home of the average musician. | |

Miklos Rozsa with friend Scott Dawes (to whom all of us should be

indebted for providing these photos). Scott is holding an LP recording of

one of Dr. Rozsa’s soundtracks: "King of Kings".

The display case near the window contains miniature ancient Greek, Etruscan

and Roman sculptures. Miklos Rozsa with friend Scott Dawes (to whom all of us should be

indebted for providing these photos). Scott is holding an LP recording of

one of Dr. Rozsa’s soundtracks: "King of Kings".

The display case near the window contains miniature ancient Greek, Etruscan

and Roman sculptures.Dr. Rózsa had asked me to phone him when I arrived in Los Angeles. When I called, the very first thing he said to me was, “The son of a b**** gave an interview – in which he compared my concerto to the music of Bartok and Hindemith!” Dr. Rózsa was, I soon learned, referring to the soloist in the approaching performances, and I may have been the first person he had spoken with after he had read that interview, the effects of which were still perceptible in his mind, palpable in his voice, and which explain his vivid reaction and explicit but understandable choice of language. (It was the only time I ever heard him use a “dirty” word). I envisioned an interesting headline in the next issue of the local papers had Dr. Rózsa been thirty years younger and in better health. Tranquility soon returned and he invited me to his house, and added, “But I can’t offer you dinner this time.” I assured him that it was only a visit I wanted, not his food, and that the privilege of spending some time with him would be all I’d ask. I expected nothing and I asked for little, but everyone has the right to hope. I was ultimately graced with a good deal more than what I or anyone might have expected. | |

The three Academy Awards (for

"Spellbound", "Double Life", and "Ben-Hur"),

among other honors, including the Abraham Lincoln Award. The three Academy Awards (for

"Spellbound", "Double Life", and "Ben-Hur"),

among other honors, including the Abraham Lincoln Award.The composer was unable to attend any of the rehearsals but he was at the first performance of the concerto, held on Thursday evening, January 14th, 1988, at the Los Angeles Music Center’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (for years the site of the Academy Award ceremonies). André Previn conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic with Pinchas Zukerman as viola soloist. During the intermission, I was talking with Dr. Rózsa. A grey-haired, distinguished-looking bespectacled man in a powder-blue blazer approached the composer and spoke with him about the concerto. The composer interrupted the gentleman for a moment, looked at me, and, pointing to the man, said to me, “Jeffrey, meet David Raksin.” On my second visit to Dr. Rózsa’s home that week, I met for the second time the late film historian and author Tony Thomas, whom I later learned was a frequent visitor to the Rózsa home. It was Tony Thomas who wrote in Music for the Movies, one of his many books, that among all the convoluted film folk in Hollywood, the composers were among the sanest and most enlightened. | |

Some

of the composer’s many Dutch, Flemish and Hungarian paintings that grace the

living room. The house was purchased in the 1940s from actor Richard Green

and his wife, actress Patricia Medina. The home was built in the 1920s for

John Bowers, whose tragic death prompted the story,"A Star Is Born". Some

of the composer’s many Dutch, Flemish and Hungarian paintings that grace the

living room. The house was purchased in the 1940s from actor Richard Green

and his wife, actress Patricia Medina. The home was built in the 1920s for

John Bowers, whose tragic death prompted the story,"A Star Is Born".On my first visit to the Rózsa home, however, I had a totally “private audience” with the composer for several hours. I also had a repeat-performance of this kind of experience the following year in Michigan, when a man named Elmer Bernstein invited me for what turned out to be a chat between the two of us in his hotel suite for the better part of an hour, and then dinner the following evening with him and his wife, Eve. I certainly knew what Dr. Rozsa meant when on my arrival at his home he offered me “. . . something more fiery” than tea, though it was only much later that I learned he’d offer guests an apricot brandy that could have taken the varnish off the coffee-table in front of me. “After drinking this, you’ll be speaking in Hungarian,” he’s reported to have said. I told him alcohol has never agreed with me, but that I once tasted Slivovitz, a brandy-type drink made from fermented plums my paternal grandfather used to enjoy (but which never, ever, seemed to be strong enough for him), and that I was glowing for weeks afterward. Dr. Rózsa served me tea & cookies. I had already been told by his son, Nicholas (who had given me driving directions for my taxi to the Rózsa home) that this was a long-standing tradition in the Rózsa household, and since then I’ve heard the same thing from a number of different sources, independently of each other, who had the same experience when visiting the composer at his home. We’re creatures of habit. Dr. Rózsa was as loyal to his tea & cookies tradition for his guests as he was to imitative writing, one of his favorite compositional tools. | |

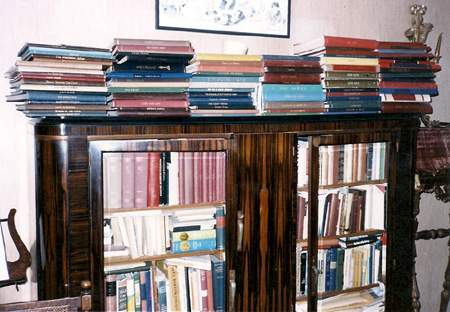

Resting atop this bookcase in the composer’s studio are the bound film

scores, nearly 100 in number. Resting atop this bookcase in the composer’s studio are the bound film

scores, nearly 100 in number.The cups & saucers were Wedgwood – real antique Wedgwood – and the teapot was evidently solid silver. (The lid was loose and the composer told me to be very careful when pouring). The spoons, also silver, seemed to have weighed a pound each and I was convinced that had I dropped one on my foot I’d have broken a toe. The thought occurred to me at the time that the beauty and worth of the teapot and the heft of the spoons corresponded fittingly to the substance of the composer’s music. We know from his memoirs that he had his family with him while he was in Spain during the composition of the score for "El Cid" – but I later had the pleasure of hearing from his daughter, Juliet, who told me that the tea service was purchased there at that time. | |

The hallway entrance to the studio. One day three years after these

photos were taken (see below), I sat with Dr. Rozsa on that seat at the left

while he asked me to remove a number of those letters and manuscripts from

the walls, one at a time, and told me the story behind each of them. The hallway entrance to the studio. One day three years after these

photos were taken (see below), I sat with Dr. Rozsa on that seat at the left

while he asked me to remove a number of those letters and manuscripts from

the walls, one at a time, and told me the story behind each of them.Near the entrance to his living room I saw the official Vatican document he had received, signed by Pope John Paul in honor of the composer’s 80th birthday the year before. I examined the large book containing the congratulatory letters (most of them hand-written) which he had received in that milestone year from dozens of people, including, to name but two, Gregory Peck and Elmer Bernstein. I held and examined his Oscars, I sat in the very chair in which he was photographed, holding & reading a score, for the RCA LP album (remember those?!) of the first recording of the Notturno Ungherese, on which he conducted the RCA Italiana Orchestra; that photo is one of the best I’ve ever seen of him and the image seems to capture his character. He sent me upstairs – the house is built on five levels around a central spiral staircase – where I met Mrs. Rozsa briefly. She told me I had given her a start because for an instant she thought I was her brother. Visiting her at that moment was Mrs. Abraham Marcus, widow of Dr. Rózsa’s long-time friend and lawyer. Dr. Rózsa also took me into that place in his home which interested me more than any other: his studio, his sanctum sanctorum, where I saw, among myriad other delectables, his Bechstein piano. The connection between Rózsa and his fellow-countryman Franz Liszt – the Leonard Bernstein of his day – wasn’t just one of nationality: the piano in Liszt’s house on Marienstrasse in Weimar, Germany, is also a Bechstein – a massive concert grand – on view there even today. Conspicuous in his studio was an electronic enlarger, similar in appearance, function and purpose to the type of machine used years ago to keep score in a bowling alley. It was the composer’s now seriously failing eyesight that necessitated the acquisition of this apparatus, which enabled him to see the music he was writing down. By its use he endowed us with at least one more work for solo instrument. | |

Taken in January, 1988: Yours truly with Dr. Rozsa in his living room.

This is the last photograph

of the two of us in each others’ company. The original snapshot was in color

but had to be

rendered in black & white for reproduction as the Frontispiece of my book,

A Composer’s Notes: Remembering Miklós Rózsa (iUniverse, 2006). Taken in January, 1988: Yours truly with Dr. Rozsa in his living room.

This is the last photograph

of the two of us in each others’ company. The original snapshot was in color

but had to be

rendered in black & white for reproduction as the Frontispiece of my book,

A Composer’s Notes: Remembering Miklós Rózsa (iUniverse, 2006).The film scores, all bound, were in plain view, but at the time of my visit were scattered helter-skelter atop a large credenza. The whereabouts of his original manuscripts of his abstract (i.e., non-film) music, however, were not as evident. When I asked him where he kept them, he pointed to a file cabinet in a corner of the studio. It seemed very apt that his film scores, being more conventional than his orchestral, piano, chamber and other works intended for recital or concert performance, were more “accessible” even here in the composer’s own studio, than his orchestral and other scores, which he kept hidden from view. If only there had been more time, I’d have asked to see, even if only briefly, his holograph score of the Notturno Ungherese, one of my favorites among all his works. His studio was reached through a narrow hallway. It seemed almost every square foot of wall space was lined with autograph letters (and some manuscript pages) of the composers, mounted in special frames so that when turned around the overside of each letter could also be read. The only major composers not represented, he told me, were Bach and Beethoven. Name any other representative composer and at least one example of his letterhand could be found there. Dr. Rózsa even had a letter written by Robert Schumann’s mother. Brahms, Wagner, Chopin, Liszt – name them, and there they were. As a music historian, researcher, author, and charter member of the Miklós Rózsa Society I’ve learned and remembered many things during the years. One of them is the pride in life and fulfillment in living that music inspires in many of us. Miklós Rózsa believed in this concept, and in me his music reinforces these sentiments. I’ve been called by some a real idealist and by others an ideal realist. Both views have merit. What I will never forget is what Dr. Rózsa said to me, before I left his home on that memorable day: “Thank you for coming to see me. May God bless you, Jeffrey.” Indeed He has. | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 21-01-24 |