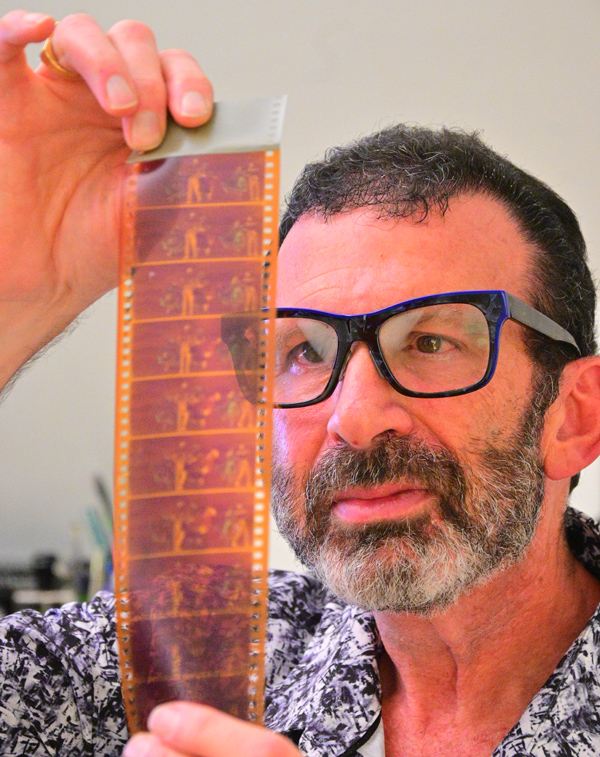

Theo Gluck and the Interest in Movies |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Interviewed by: Thomas Hauerslev, Tuesday, October 3, 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark. Edited by Mark Lyndon, in70mm.com, London | Date: 01.01.2024 |

Thomas Hauerslev: How did you become

interested in movies? Thomas Hauerslev: How did you become

interested in movies?Theodore E Gluck: I became interested in movies at a very young age. Growing up in New York City, there were tremendous opportunities at specialty cinemas like the Thalia which was only about 10 blocks from where I grew up. Both of my parents were university professors and rather schooled and aware of all the arts. And they were big movie fans themselves. Many films I originally saw for the first time, I was introduced to by my parents. My love of Tom and Jerry cartoons came from my father's love of them. My mother was an art historian and art professor. Visiting the Museum of Modern Art and seeing German expressionist films and a lot of Dadaist and surrealist films from the 1920s, when I was 10-11 years old, was not out of the realm of possibility. So, from a very early age, I was made aware of not only what the art form can do, but I was also intrigued by the technology to create that art. How did they do what they did? THa: And in your early years, were you involved in cinemas as a projectionist? Theo: Ever since I was a boy, I was always fascinated by the notion of projection. I always wanted to try to get to a booth to see how it worked. In 1977, I had the opportunity to meet Robert Endres, who was the Chief Projectionist at Radio City Music Hall. My twin brother and I were at the Hall to see, of all things, a four-track mag print of "Fantasia". We approached the manager that was on-call that day and said, "Is there any chance we could see the projection booth?" And He looked at us like, "OK, you're just a couple of high school kids, but OK, sure". Went upstairs and met Bob. We started asking him questions and Bob was like "These are really informed questions. Who the hell are you guys?" Through him, I met another fellow named Michael DiCosimo, who ran the Dolby HQ in New York for many years. Both of these men were mentors, teachers, and scholars and were very giving and generous of their time answering my questions. Nearly 50 years later, we’re still friends. I also learned from them both the important notion of “paying it forward.” I am presently a mentor through the Academy’s Gold Rising Program. My philosophy with those interns is that I want to be a resource for them that I wish I had when I was them. I think that's the most noble calling any of us who find a love of this kind of technology and this aspect of the cinema needs to continue to do. • Go to The Cinerama Archaeologists • Go to Die Cinerama-Archäologen • Go to Kevin Brownlow & "Napoleon" THa: Did you become a projectionist? Theo. Ah yes, I did. I was a projectionist in New York City, Local 306 of IATSE, a proud card-carrying member. I want to say I became a member like 1983, 1984 and I continued until I left and moved to Los Angeles in 1991. Primarily, I did a lot of work at, of all places, the Todd-AO film mixing facility which is a recording facility for mixing movie sound. So it was a great thrill to work at a Todd-AO branded installation even though we did not have vintage DP70s. We did have 35/70mm (Simplex if I recall correctly). I also went to other cinemas around Manhattan. I learned on carbon arcs as they were still quite common in New York cinemas at that time. And actually, by the time I left, platters were a thing, but not as huge as they became. I never learned on, or was ever certified as a platter operator. I only knew reel to reel changeover. THa: How did you become involved in movies and cinema when you moved to Los Angeles, in 1991? Theo: I had been working in New York. Both at Todd-AO and other cinemas, all through the Projectionist Union. I was also reviewing cinemas and their performance for the Lucasfilm Theater Alignment Program. Someone at Disney reached out to the Lucasfilm Alignment people (with whom he dealt with for the Disney product) and said "I need someone for my team who knows film, not video, but understands film. Help me find someone in Los Angeles". Lucasfilm told him:

So Lucasfilm calls me that evening and says

"Someone at Disney asked us for a recommendation for his team. Relax, it's

not you, but can you do us a favor and just fax us your resumé?", which in

February of 1991 meant finding a stationary store that will charge me $1.50

a page to fax a two-page resume. And I told myself, you know what? I'm going

to wait two months. I will call Lucasfilm back and say "I'm just curious.

Whatever happened with that?". And absolutely I faxed my resume. Two hours

later, Disney called. One week later, I'm in Burbank being interviewed, and

25 days after that interview, with all the clean clothes I could muster

under my left arm, my cat under my right arm, a moving van with the rest,

and with a one-way plane ticket from Disney, I moved to California. On April

1st, 1991, I started work as Manager of Film Operations for the [Disney]

company. As I like to say, spending 25 hours a day, eight days a week at

Technicolor on printing assets and printing issues. Within five or six

months of starting, I had meetings in Technicolor London and Technicolor

Rome, and on that trip detoured to Frankfurt to look at a cinema

installation to see about running a double system version of "The Beauty

and the Beast", work in progress version. Talk about baptism by fire.

For the next 30 years I was involved in a myriad of projects at the Studio,

and in 2004 I was asked to head up the restoration and preservation team.

|

More in 70mm reading: Kevin Brownlow & "Napoleon" Cinerama, David Strohmaier and the "We have all seen it as a kid" thing The Cinerama Archaeologists Die Cinerama-Archäologen History of Technirama in70mm.com's Library “Sleeping Beauty”: The North American 70mm Engagements “The Black Cauldron”: The North American 70mm Engagements “The Big Fisherman”: The North American 70mm Engagements Presented on the big screen in 7OMM Peripheral Vision, Scopes, Dimensions and Panoramas |

THa: What does the

Director of Library Restoration and Preservation do? THa: What does the

Director of Library Restoration and Preservation do? Theo: What a preservation and restoration person in the studio does, I think, depends on what the studio feels is important for them to restore and preserve. The Studio Operations group has a great team in the vaults, and they also built an amazing new film archive on the lot that opened in 2014. On the restoration side, especially with the classic features, it was done in collaboration with Disney Feature Animation for creative guidance, as well as with Home Video, because they knew what they needed to sell, so we knew what films to start with. We didn't really start with the A's and work our way through the Alphabet. As I like to say, the mantra of any restoration project is first "do no aesthetic harm". What you think you should do doesn't mean you should do. In the days of HDR (high dynamic range) and Dolby Vision just because you can “turn it up to 11”, doesn't mean you should. You can make "Snow White", “Bambi” and “Pinocchio" look iridescent, look neon but that was not the artistic values within the film to begin with. Aside from the fact that the color palette of the film never exceeded those values that had that kind of chroma in it. Also, there was no way to view it and to present it in a way that no one actually filmed for that, and that's why you consult with feature animation artists and scholars. We used to work with the sound department as well, because if they want to do a new restoration, say of “The Godfather" titles, Francis Ford Coppola can weigh in. You can get Gordon Willis to give his advice and thoughts on it. But who speaks for "Bambi"? Who speaks for "Singing in the Rain"? Who speaks for "The Wizard of Oz"? I like to say you “triangulate” amongst the best extant copies you have, all the research you can possibly do, and then understand that personal opinion that is foisted as fact accomplishes nothing. It was a collaborative effort to make these films and it is a collaborative effort to save them. Ensuring that they look as best as they possibly can and present them as they looked on the first day of release, is what they should look like when restored. THa: What's the difference between restoring and preserving a film? David Strohmaier also has an expression for what he does and that is remastering the film. Theo: The three main pillars for me are: restoration, preservation and reconstruction. Remastering falls under that as well. When I started in this business, remastering invariably meant a new standard def telecine of an interpositive (IP) to a “newer” video format such as D2 or DigiBeta. The advent of HD telecines required yet another “remaster,” and with these transfers destined for HD displays now (finally) in their correct aspect ratio and not a pan-scan 4x3. The introduction of precision film scanners which can gently accommodate original camera negatives and capture their inherent image energy and integrity have ushered in the new generation of digital restorations. In many cases, preservation can be the simultaneous byproduct of a restoration. Take a Disney project like "Bambi" for example. The project started with 4K scans of the original nitrate successive exposure (SE) camera negative, so right from the start the project yielded a digital preservation of the negative. Additionally, a new successive exposure, black and white safety negative was rendered from those aforementioned preservation scans, so that is now an analog/celluloid back-up of the negative. It should be noted that this new safety SE negative is a “raw” element and is a true record of the SE original without any image manipulation or dirt removal. Extraordinary advances in digital restoration tools and color correction platforms have brought about amazing results. I am continually amazed whenever I see “before and after” examples of what heretofore would have been considered irreparably damaged frames. There are two issues unique to SE cel animation restoration. First and foremost is tackling the dirt and dust that are on the backgrounds, the cels, and even the animation stand platen to hold the set-up steady under the camera. Every time you move a cel, the dirt and dust that are on the background will move. As a result, and given the clarity afford by the digital scans, you get stop motion animation (think "King Kong" or any Harryhausen film) of that dirt and dust that was captured during the original photography. Remember that the original Technicolor dye-transfer “IB” prints shown in a cinema were by their nature multiple generations away from the camera negative. I like to refer to them as a sprocketed, flexible, moving lithograph. As a result, those prints could never showcase the detail held by the negative, hence the dirt levels were less noticeable on-screen. 4K scans of the negative changed that dynamic as there’s nowhere to mitigate those flaws. The second issue is addressing the artifacts from physical distress on the SE (or YCM) negatives themselves. With a “single ribbon” negative, be it black and white or color, any physical dirt on the actual negative manifests itself as white specs on screen. Physical dirt on SE/YCM separations reveals itself as either red, green, or blue issues on the screen, depending upon which record has the dirt. Given that SE/YCM negatives were used only to generate printing elements but were not used to make release prints means that those film elements remain in fairly decent shape. For cel animation restoration, the greater challenge is wrestling with what has been captured during photography (and now far for more visible in the scans) and not the condition of the negative itself. |

|

Thomas

and Theo with the "Bio" sign from the 3 Falke Bio in Copenhagen.

The first Todd-AO cinema in Scandinavia (1958). Picture by: Charlotte Hauerslev Thomas

and Theo with the "Bio" sign from the 3 Falke Bio in Copenhagen.

The first Todd-AO cinema in Scandinavia (1958). Picture by: Charlotte HauerslevTHa: How are negative and sound elements for large format stored? Theo: Well, in theory, Ideally, all film negatives, regardless of gauge from Super 8 to IMAX, and their attendant sound assets should be stored with great attention to both the humidity and temperature levels of the vault. Light, moisture, and heat can affect color dye stability. Kodak recommends that negatives should be stored just above freezing at 2°C (36°F) with relative humidity levels at around 20 to 30 percent. I know some people advocate freezing negatives and that's certainly one approach, but extra care needs to be used when acclimating those elements to ambient room temperature to avoid any excessive moisture from thawing that could impact the film. My best advice is to dress warmly if you’re going to spend any time in any time in a proper film vault. Sound elements must also be kept under the aforementioned environmental controls. That would certainly apply to nitrate optical sound film elements. Older magnetic oxide formulations will shed if improperly stored, and in many cases mag reels have to be ‘baked” to re-adhere the oxide to the base to get an archival playback pass. So, the SE nitrate 35mm original camera negative for "Snow White" for example, is at the Library of Congress in their nitrate storage facility. But safety single ribbon color duplicate negatives or printing elements would be stored elsewhere. Geographic separation of your original assets and their protection elements is always a smart idea. THa: But is it, as an example, the "Sleeping Beauty" negatives and the sound elements that are stored in the same vault or is it separate? Theo: No, they will be separate housed in separate locations. The original Technirama negative for "Sleeping Beauty" would be housed in the Disney studio lot in their new film vault. THa: Are there copies of those negatives, I mean it's printed like successive exposures? Would there be copies of that stored elsewhere in case you need that? Theo: Yes, there are because there was also work done before I came on board with that restoration, and 65mm protection IPs were done as well. Remember that for either 70mm or 35mm prints of "Sleeping Beauty", there was the on-camera 1.25x anamorph [squeeze] you had to correct for. Either blow it up/un-squeeze to accommodate the 70mm frame or full anamorphic 2:1 squeeze for 35mm CinemaScope prints. The good news is that you can correct for the anamorphic distortion digitally without the added optical steps when working photochemically. THa: Do you think that the studios actually go back and look at all restorations again with new tools? Theo: Certainly. Disney recently premiered a new 4K UHD HDR restoration of "Cinderella” on Disney+. Better scanning opportunities, wider color gamut, improved restoration tools, and UHD home monitors all make for a better experience. THa: Can you describe what's it like to go into the vaults to actually look for the necessary elements? Is everything clearly labelled? Was that you who did that, or did you have some staff to assist you? Theo: When searching for the materials, the studio has a very robust Inventory system and a very knowledgeable staff, so we would let them know what we were looking for. In some cases, we were quite lucky. Perfect example is ... and again this research would have been done by the Library of Congress because they had the nitrate ... is when, in 1953, the Studio left RKO for distribution and began Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, the original title sequences were revised/re-filmed to remove the RKO references changed over the years. And "Snow White" is a perfect example. The Studio had removed the original RKO branded title sequence from the SE nitrate negative for the early 1950s re-issue. Luckily it had been saved and was with the other assets for the film at the Library of Congress. So the original “as released” opening for "Snow White" was seen for the first time in over 50 years. |

|

Thomas

and Theo in front of the Grand Theatre (1913) - oldest cinema of

Copenhagen. Picture by: Cindy Goldberg Thomas

and Theo in front of the Grand Theatre (1913) - oldest cinema of

Copenhagen. Picture by: Cindy GoldbergTHa: Have you yourself been to these vaults at Disney? What was it like for you to see all those huge shelves? Theo: I like to say that for most men in America, it's a trip to Cooperstown and the Baseball Hall of Fame. For me, it's a trip to the nitrate vaults at the Library of Congress. The fact that I was able to see the original camera negative for "The Great Train Robbery" or hold the YCM cans for "Flowers and trees", which is Disney's first Technicolor short. That's an absolute thrill. I never tire of going to the any vault and seeing what is on the shelves. I would drive film labs crazy when might be in their vaults on my own project, but see something else in there and ask "Hey, why do you have these cans of film here on this project?" Like maybe I was not supposed to know they were working on it, but I always love to see what's in progress. So yes, it's always a thrill to go to those archives. THa: That goes back to your beginning of being interested in movies and go into the Hall and ask clever questions ... Theo: Another source for forensics fun is looking at leaders. I love film leaders. Some of the leaders on the early Disney three strip Technicolor shorts (before they switched over to SE photography in 1936/1937) are actually slugged with old two-color leader for just filler. Some amazing images show up on those leaders because we scanned the entire full length of the negative. I found a few frames of someone holding a framing and resolution chart. I just thought it was so cool. THa: You read about lost film and sound elements. "Lawrence of Arabia" is an example where the entire soundtrack was missing and he [Robert A Harris] had to pick that up from existing 70mm prints. Theo: Or in other cases, have the actors re-record their dialog. Tony Curtis came in to loop his missing dialog from the infamous “oysters and snails” sequence in ("Spartacus"). It was then pitched up a slightly so he would sound younger. Anthony Hopkins re-voiced the missing Laurence Olivier dialog. They even had to resupply the score and all the missing sound effects. That represents the extreme type of work that might need to be done, and I absolutely applaud the results. I rather do something to support the film rather than do nothing at all. THa: Is that normal that elements for a film like "Lawrence of Arabia" are missing? Theo: Unfortunately, it can be. You always want the original negative, but there are many, restoration projects where they needed to use any combination of interpositive, internegative or even separation elements that were made for protection on a color element if the original negative has just decayed or it's too damaged. So, it's not unheard of. My philosophy has long been that I never blame anyone or ever point any fingers because "Oh my God, you couldn't find it?". I know the effort it takes to do rescue and resuscitate these titles. I totally support my comrades in arms who do this type of work. THa: My last question in that chapter, where are all these things we briefly talked about it in Library of Congress and locally at Disney. But you also mentioned Iron Mountain. What is Iron Mountain? Theo: Iron Mountain is a global company that does secure and climate controlled deep storage and preservation of everything from paper records/documents to film, video, and audio assets. Many of the studios keep safety elements and for both picture and sound with Iron Mountain. UV&S (Underground Vault and Storage) in Kansas City is another key strategic partner for the Studios when safeguarding assets. THa: So those vaults would be where all the movie companies store their assets? Theo: Yes. Certainly, some strategic safety assets would likely be there. Walking through the state-of-the-art nitrate vaults in Culpeper, VA, at the new NAVCC - The National Audiovisual Conservation Center, is breathtaking. Behind one door is could be “The Best Years of Our Lives”. Another door has "How Green Was My Valley" and "The Grapes of Wrath". Another door has "Pinocchio", "Snow White", "Dumbo". The level of fire suppression and combustion prevention that's in place in that facility is a staggering. |

|

THa:

How did you decide if a film needed to be restored? Was that your

responsibility? THa:

How did you decide if a film needed to be restored? Was that your

responsibility? Theo: It was a collective responsibility for determining how a Disney film was restored, or what, more importantly, when it needed restoration, was primarily on usage alone. If a film was having a specific anniversary, then budgets would be put together to determine the costs and time required. When Home Video decide to celebrate the 50th anniversary of "Mary Poppins” that was the first time we scanned the negative and went back to the original stereo mag elements. For "Sleeping Beauty", the studio decided to use that film as their first Blu-ray release of a classic animated feature. Having been photographed in Technirama the film was the perfect candidate for Blu-ray release, which is why we scanned the original SE camera negative, which incidentally is over 7.5 miles long. The musical score is an integral part of the film so we were able to locate the original 3-track stereo music recordings that were done in Berlin. Prior video masters would use the “sounding master” which was a the LCRS four-track mag element that would be used to dub (copy) sound onto the 35mm CinemaScope mag stereo and 70mm release prints. We found the original music masters and brought in a music editor to ensure that we're using the correct takes. We did a demonstration for the head of Home Video to show him what it had sounded like and what it now could sound like. He gave us his blessing as well as the time and funding to fully remaster the audio. Titles such as "20,000 Leagues Under The Sea" (the Studio’s first CinemaScope feature), "Swiss Family Robinson" and “Pollyanna” had color negatives in various stages of fading (as do all color negatives of that era) so these were given priority as well. THa: How do you approach a restoration? Theo: The best way to approach a project and again, I'm speaking from my experience and uniquely with animated features, would be to first review prior video masters to see what challenges they faced without modern digital restoration tools. These could be color fringing problems as the prior master sourced an interpositive where you couldn’t optically realign the color records with the exacting precision you can now. Additionally you can discern where there will be issues with dust and dirt that again, were beyond the reach of some earlier image clean-up tools. Equally important is a full physical inspection of the negative to confirm it can be safely placed on a scanner. Ideally you should not be putting an 85-years old nitrate camera negative on an optical printer. But a scanner that slowly advances the film a frame at a time and be watched like a hawk is where it belongs now. Once you have the scans, and in the case of color separation film, be it SE or YCM, you can put those together with a rudimentary color grade. Essentially, a one-light pass so you can see what you've got to deal with. Then you can really start looking at what the issues are. The scratches, the weave, the dirt. And really at that point it's much like a composer might spot a film for where the cues will go. That's when you really understand, "Oh boy, we got our work cut out for us". THa: What about the sound for "Sleeping Beauty"? It was presented in wonderful Super Technirama 70 and six track stereo. Was it really recorded in six track stereo in those days? Theo: I think a lot of films that heralded themselves as 6 track were really not bona fide 5 discrete channels (Todd-AO Ortho-Sonic) behind the screen. In the case of "Sleeping Beauty", some of the documentation we found clearly spelled out an LCRS [left, center, right, surround] 4-track mix. However, we had a vintage 70mm print that we played back in the main theater and brought it into ProTools for analysis, and you could see quite readily how it sloped off from the center. So when Todd-AO sounded the 70mm prints using the 4-track master, they blended channels 1 and 3 into 2 and channels 3 and 5 into 4 behind the screen. At that time, 70mm houses still likely had five channels behind the screen, but "Sleeping Beauty" was never not designed that way. It was never a true discrete 5 channel on-screen mix and only had a mono surround. THa: What about “The Black Cauldron” in Technirama. Any work done on that one? Theo: Yes. There was a new restoration of “The Black Cauldron” done in 2017 (if I recall correctly). We did access the original SE Technirama negative. The 4K 16-bit scans totaled 36TB. THa: Was the "The Black Cauldron" also photographed in successive exposures, in multiplane and everything? Theo: It was, yes. All of the successive exposure films have had multiplane sequences, starting with "Snow White" and certainly the whole opening of "Bambi" is amazing, and then the beginning of reel two in "Pinocchio". THa: "The Black Cauldron" was a mid '80s film. Did they still use the multiplane in those days? Theo: Yes, but to a far lesser extent than in the early films. The Camera Department in Feature Animation told me that “The Rescuers Down Under" (1990), was the last feature to utilize the multiplane camera on a couple of shots. THa: How about “The Big Fisherman” in Super Panavision 70? Theo: It was discussed, but not much ever came of it under my time there. Everyone knows it's there, but it was never deemed a priority during my time there. THa: How do you see restorations in the next years? How will that evolve in your opinion? Theo: I think restoration will continue to evolve and continue to grow greater because studios realize that viewing audiences have become more sophisticated and more demanding over time. And they want to see these titles and I think any studio, let's not kid ourselves, wants to monetize what they have. And the way you get more people's eyeballs back on them is to clean them up. So I'd like to think that studios will continue to recognize the importance of these films and whether you will ever see them on film in the cinema seems more doubtful every day; but I'd rather see them presented somehow to audiences, much like the Cinerama travelogues, than never see them at all. THa: Thank you |

|

• Go to Theo Gluck and the Interest in Movies |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 21-01-24 |