"In 70mm and 6-track Dolby Stereo" |

This article first appeared in |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Written by: Thomas Hauerslev from Dolby's material | Issue 62 - September 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Further in 70mm reading: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Most

famous tagline of top-of-the-line cinemas through the 1980s Most

famous tagline of top-of-the-line cinemas through the 1980sThe original 6 discrete uncompressed channels were reconfigured into a left, center and right screen channel plus a surround channel (renamed from effects channel). Except for a few rare 70mm show-prints (that used the original 5 discrete channels behind the screen with directional dialogue) used in major first run cinemas in Los Angeles, New York and London, the sound was now "folded in" in such a way that most dialogue came from the center channel. The tag line "In 70mm and 6-Track Dolby Stereo" was a clever marketing gimmick that for 20 years and nearly 250 films secured the best possible sound reproduction in the cinema. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A

Brief History of Dolby Laboratories

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby's Business Philosophy |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Design

Excellence, Responsive Service, Long-Term Results. Design

Excellence, Responsive Service, Long-Term Results. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Worldwide Facilities |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby

Presentation Cinema in San Francisco Dolby

Presentation Cinema in San FranciscoDolby Laboratories' corporate headquarters, housing research and development, marketing, licensing and administrative staff, is located in San Francisco's historic Potrero Hill district, in a renovated brick warehouse dating from the early 1900s. The facility includes a state-of-the-art film screening room and listening and testing facilities for the wide range of consumer products incorporating Dolby technology. North American manufacturing operations, using the latest in surface mount and other current manufacturing processes, are housed a short distance away in Brisbane, California. This site serves customers throughout the Americas, Japan and Korea. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby

Laboratories' office in San Francisco, USA Dolby

Laboratories' office in San Francisco, USADolby Laboratories' European base, in the Wiltshire, England countryside, is home to marketing, licensing, administrative and manufacturing staff serving customers in Europe and Asia. This facility, constructed to Dolby's specifications, includes a screening room and full-scale manufacturing operations which also use the latest in surface mount and other current manufacturing processes. Additionally, Dolby Laboratories maintains two film division offices, located in New York and Los Angeles, to provide on-site, responsive service to filmmakers and recording professionals working on Dolby sound mixes. Both offices host frequent technical seminars and other events of interest to the behind-the-scenes film and audio community. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby Investigates Film Sound |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In

the late 1960s, even as home stereo B-type noise reduction was coming to

market, Dolby began to look further a field for applications of its noise

reduction technology. One area that looked promising was film sound, in

particular, the photographic or "optical" soundtrack, introduced

in the late 1920s. Thanks in great part to Dolby's efforts, that analog

optical track is still by far and away the most popular way of providing

sound with film. In

the late 1960s, even as home stereo B-type noise reduction was coming to

market, Dolby began to look further a field for applications of its noise

reduction technology. One area that looked promising was film sound, in

particular, the photographic or "optical" soundtrack, introduced

in the late 1920s. Thanks in great part to Dolby's efforts, that analog

optical track is still by far and away the most popular way of providing

sound with film.The optical soundtrack has many advantages, including economy, reliability, and relatively long print life. Equally as important, 35 mm film with optical sound is a truly universal medium: a film made in the U.S., for example, can play in theaters the world over. This universality, however, had its downside. To forestall compatibility problems after a decade of theaters racing to install differing sound equipment and filmmakers rushing "talkies" into production, in the late 1930s the film industry adopted a standardized theater playback response that today is called the "Academy" characteristic. While this resulted in a relatively uniform system of recording and playback that made it possible for just about any film to sound acceptable in any theater in the world, it lacked the flexibility to incorporate improvements beyond the limitations that existed in the 1930s. Indeed, well into the 1970s conventional optical sound reproduction in film theatres had a frequency response little wider than a telephone's. Upon investigation, Dolby found that the many of the limitations in optical sound stemmed directly from its significantly high background noise. Essentially to filter this noise, the high-frequency response of theater playback systems was deliberately curtailed (the "Academy" characteristic). To make matters worse, in order to increase dialogue intelligibility over such systems, sound mixers were recording soundtracks with so much high-frequency pre-emphasis that high distortion resulted. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Slow Start |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"IN

70MM Dolby Stereo" was a major tagline on any respectable release during the

1980s. Here's an example with "Amadeus" which ran more than a year in the

same cinema in London's West End "IN

70MM Dolby Stereo" was a major tagline on any respectable release during the

1980s. Here's an example with "Amadeus" which ran more than a year in the

same cinema in London's West EndDolby conjectured that applying Dolby A-type noise reduction to the optical sound track would make it possible for wider frequency response in the theater on the one hand, and for mixers to record "flatter," less distorted soundtracks on the other. The result would be - as experiments ultimately proved - significantly higher fidelity optical sound. Dolby then went on to develop an A-type noise reduction unit specifically for use in movie theaters, which incorporated a special equalizer to widen the response of theater speakers without their having to be replaced. The compatibility of movie prints with A-type encoded soundtracks heard in theaters without a Dolby decoder was tested and judged acceptable, much as B-type encoded cassettes were being accepted as compatible when played on non-Dolbyized players. Thus, when lobbying with the film industry to produce encoded films, Dolby could argue that only one type of release print would be needed for all theaters. This first attempt at involvement with film sound met with only modest success, however. While the improvement in fidelity was unquestionable, optical sound was still mono. By this time, superior hi-fi stereo systems had been installed in so many homes that a significant proportion of the movie-going public was accustomed to better sound at home than could be heard in the theater. And since the 1950s, the movie industry had had at its disposal a different soundtrack method that provided multi channel stereo sound. With this alternative method, narrow stripes of iron oxide material similar to the coating on magnetic recording tape are applied to the finished release print. The sound is then recorded on the magnetic stripes in real time. The film is played back on projectors equipped with magnetic heads similar to those on a tape recorder. While many theaters had been equipped for magnetic sound in the 1950s, however, by the 1970s the expense of magnetic release prints (more than 10 times that of optical prints), their comparatively short life compared to optical prints, and the high cost of maintaining theater magnetic equipment led to a massive reduction in the number of magnetic releases and theaters capable of playing them. Magnetic stereo sound came to be reserved for a only handful of first-run engagements of "big" releases each year. By the time Dolby came on the scene, movie-goers were again usually hearing low fidelity, mono optical releases, with only an occasional multitrack stereo magnetic release. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The formula for film sound success |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby

Laboratories CP50 cinema processor for 35mm optical sound playback Dolby

Laboratories CP50 cinema processor for 35mm optical sound playbackRecognizing that the film industry was not eager for an improved mono format, Dolby Laboratories went on develop a true breakthrough: a highly practical 35 mm stereo optical release print format originally identified as Dolby Stereo and introduced in 1975. In the space allotted to the conventional mono optical soundtrack were two soundtracks that carry not only left and right information as in home stereo sound, but also, by means of a matrix encoding process, information for a third, center-screen channel and a fourth surround channel for ambient sound and special effects. Yet the new track was configured to be entirely compatible with mono playback, requiring the issuance of only one kind of release print. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby

Laboratories CP100 cinema processor for 70mm magnetic 6-track playback Dolby

Laboratories CP100 cinema processor for 70mm magnetic 6-track playbackThis format not only enabled multi channel stereo sound from optical soundtracks, but also higher quality sound. As with the original mono format, Dolby noise reduction was used to lower the hissing and popping associated with optical soundtracks, and loudspeaker equalization was provided to adjust the theater sound system to a new, wide-range standard response curve. An important advantage of the Dolby optical four-channel stereo format was that prints cost no more to make than mono prints, unlike expensive magnetic prints. What's more, conversion to Dolby optical was relatively simple and once the equipment was installed, very little maintenance was required, particularly when compared to magnetic stereo playback systems. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Dolby film program |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

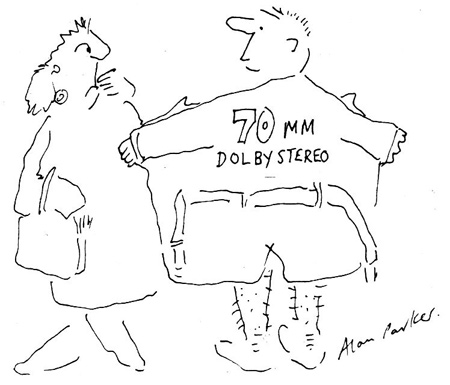

Director

Alan Parker's cartoon Director

Alan Parker's cartoon Although the potential for the new stereo optical format was far greater than the original mono Dolby format, success did not come overnight. Whereas Dolby noise reduction for professional tape recording was a relatively straightforward add-on and could be marketed as such, Dolby's new film format required significant changes throughout the film sound record/reproduce chain, and thus throughout the film industry. Dolby's ultimate goal seemed simple enough: to profit from the manufacture and sales of a new range of theater sound processing equipment. However, for that to happen, film producers had to be educated in the benefits of the new format. Sound mixers had to be brought on stream with new techniques. Distributors had to be reassured that stereo release prints were compatible with mono theaters. Theater equipment suppliers had to be educated in system requirements and installation procedures. And theater owners had to be convinced that investing in the new equipment would pay off at the box office. As a result, it was necessary to implement and staff a film sound program, not unlike the licensing program, that could reach out to all these disparate segments of the film industry. The multi-faceted, international program that resulted incorporates several key elements. These include Dolby film sound consultants who assist at the mix of films slated for release with soundtracks utilizing Dolby technology (today there are Dolby consultants in every film production center in the world). Dolby has also established offices in New York and Los Angeles to further assist the U.S. film industry, and it regularly conducts training courses to train equipment installers and technicians in the ins and outs of Dolby theater sound equipment. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

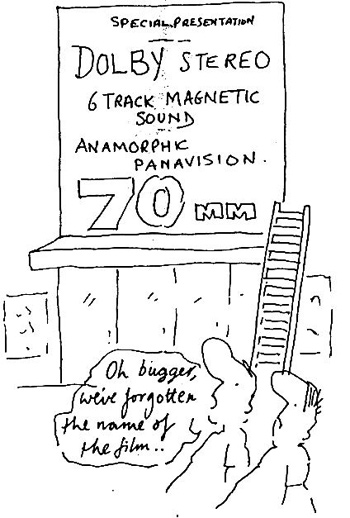

Director

Alan Parker's cartoon Director

Alan Parker's cartoonAs with other software, Dolby builds the encoding equipment necessary to produce soundtracks incorporating Dolby advances. This equipment is not sold outright, but is leased to film companies and studios, with Dolby Laboratories maintaining title. This policy, along with the quality control applied to film soundtracks by Dolby consultants, Dolby's manufacturing theater sound processors to the same standard as the encoding equipment, and the various Dolby training programs, helps to ensure the high quality presentation audiences have come to expect from "Dolby" on the marquee. While this program was being developed, one further element was needed to ensure Dolby's lasting presence in the film sound field: audience awareness. The watershed year was 1977, with the release of two immensely popular films that were recorded with the new Dolby technology: "Star Wars" and "Close Encounters of the Third Kind". These blockbusters were exhibited in just enough theaters that had invested in the new Dolby equipment for audiences and industry alike to sit up and take notice. Marketing research soon began to show that audiences would go out of their way to theaters exhibiting in the Dolby stereo format, and avoid mono presentations of the same films. While "big" films were the early adopters of the new Dolby technology, it wasn't too long before films of all types began to be released with stereo optical soundtracks. The result was a profound change in the movie-going experience. In 1976, when you went to a movie, chances were that it would have low-fidelity, mono sound; multi channel hi-fi stereo was a rarity. Today, however, when you go to the movies, chances are it will be presented with multi channel stereo sound. That is attributable directly to Dolby Laboratories and its film sound program. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

July

1987: First Dolby Stereo SR films released, "Innerspace" and

"Robocop". July

1987: First Dolby Stereo SR films released, "Innerspace" and

"Robocop".

November 1986: Release of 1000th Dolby Stereo film, "Heartbreak Ridge". November 1979: "Apocalypse Now" is first Dolby Stereo 70 mm film exhibited commercially with stereo surround (in 15 theatres). December 1978: "Superman", 50th film with soundtracks encoded with Dolby A-type, opens simultaneously in over 200 theatres; also used in first experiments with 70 mm stereo surround. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

May

1977: Opening of "Star Wars" in 46 U.S. theatres equipped

for Dolby Stereo, plus release of "Close Encounters of the Third

Kind" later in year, greatly increase public awareness of Dolby

Stereo and trigger further theatre installations. Spring 1976: First 35 mm Dolby Stereo optical film with encoded surround effects, "A Star Is Born", released.  September 1975: First feature film for general

release with Dolby Stereo optical soundtrack, "Lisztomania",

completed. September 1975: First feature film for general

release with Dolby Stereo optical soundtrack, "Lisztomania",

completed. May 1974: "Callan", first film with optical soundtrack (mono) encoded with A-type noise reduction, shown at Cannes film festival. December 1971: "A Clockwork Orange", first film to use Dolby noise reduction on all pre-mixes and masters, released with conventional mono optical soundtrack. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby Cinema Processors |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby

Laboratories CP200 cinema processor for 70mm magnetic 6-track playback Dolby

Laboratories CP200 cinema processor for 70mm magnetic 6-track playbackCP200, comprehensive theatre unit incorporating for the first time Optical Bass Extension and format programming. Introduced May 1980. CP50, economical theatre unit for reproduction of 35 mm Dolby Stereo optical releases. Introduced October 1975. CP100 introduced for reproduction of Dolby Stereo magnetic and optical soundtracks. First units installed for London premiere of film "Tommy" in March 1975. Model 364 unit for decoding mono optical soundtracks encoded with A-type noise reduction. Introduced February 1972. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby Technologies |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dolby

B-type noise reduction, providing about 10 dB of noise reduction at high

frequencies, was a simplification of A-type. It extended the use of Dolby

technology into the consumer environment, giving consumer electronic

companies the ability to make cassette tapes and players which gave the

consumer quiet recordings. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby

Stereo. After introducing the use of A-type noise reduction to the film

industry, Dolby's next major contribution was Dolby Stereo. This

contribution allowed movie makers to put 4 channels of sound information

(left, right, center, surround) on motion picture release prints using

matrix technology, and gave theaters the ability to replay this 4-channel

format for the movie going public. Dolby

Stereo. After introducing the use of A-type noise reduction to the film

industry, Dolby's next major contribution was Dolby Stereo. This

contribution allowed movie makers to put 4 channels of sound information

(left, right, center, surround) on motion picture release prints using

matrix technology, and gave theaters the ability to replay this 4-channel

format for the movie going public.Dolby Surround is the home embodiment of Dolby Stereo. Dolby Pro Logic is Dolby's second generation licensed home surround system. A major advantage of Dolby Pro Logic is the use of an active center channel with its own speaker. AC-1 was Dolby's first digital audio coding scheme. First adopted by systems providers in 1984 when bit rate reduction was in its infancy, AC-1 is a refined form of adaptive delta modulation (ADM), whereby changes in the signal amplitude from moment to moment are transmitted, rather than absolute values. AC-2 is a perceptually based adaptive transform coding algorithm that combines very high audio quality with a low bit rate, thus substantially reducing the data capacity required in such applications as satellite and terrestrial links and digital audio storage media. Dolby Digital (AC-3) is an advanced perceptual coding technology for transmission and storage of up to five full-range channels, plus a supplemental bass-only effects channel (referred to as a .1 channel due to the smaller number of bits needed for the information), in less space than is required for one linear PCM coded channel on a compact disc. Dolby E is an audio coding technology that allows a single AES/EBU audio pair, or a single pair of digital VTR audio tracks, to carry up to eight channels of broadcast-quality audio for post-production and distribution purposes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dolby Stereo Format Codes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 21-01-24 |

Ray

Dolby (1933-2013), founder of Dolby Laboratories. Image from dolby.com

Ray

Dolby (1933-2013), founder of Dolby Laboratories. Image from dolby.com

Dolby

Laboratories'

Dolby

Laboratories'

3

3