Sir Sydney Samuelson and Real Picture Quality | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Interviewed by: Thomas Hauerslev. Transcribed for in70mm.com by Brian Guckian. Proofread by Sir Sydney Samuelson and Mark Lyndon for accuracy. Images by Thomas Hauerslev, unless otherwise noted | Date: 26.08.2013 |

Sir

Sydney Samuelson in his garden. Click the image to see enlargement. Sir

Sydney Samuelson in his garden. Click the image to see enlargement.TH: We’re sitting in Sydney Samuelson’s living room...it’s Monday October 17 2011, around 3.30pm, and here we go – So Sydney, tell me about how you entered the industry – was your interest originally to work with movies and cinema? Sir Sydney: Well my interest actually came from my father, who was an eminent producer, if I may say so, in the British silent film industry. He was born in Southport, Lancashire from immigrant parents – his father came from what was then called Prussia and his mother came from Poland. And he set up virtually at the beginning of cinema in the UK – a rinky-dink cinema in a church hall in Southport. He must have borrowed a hand cranked projector from someone – he used to show a programme of films. Whether it was the first cinema in Southport, I don’t know, but in those days, you obtained – if you were showing films for money – entertainment films. You bought yourself a complete programme and then, when there was nobody left who had not seen your programme – if you lived in Southport, as my father did, you sold that programme to an even smaller cinema somewhere in your area and bought a new programme, and then showed that. And in fact, legend has it in our family that my grandmother, who was, as I said, this immigrant lady with very little English, it was she who said, “Why don’t you change things; instead of people having to buy a programme and then sell it when nobody around wants to see it anymore, wouldn’t it be better if they could rent a programme, say for a week, and for much less than it would cost to buy it outright? Then, every week, the cinema owner could put a new programme of films on and the customers would want to be coming and seeing films on a weekly basis”. |

CHAPTERS • Home: A Conversation with Sir Sydney Samuelson • Panavision, Bob Gottschalk and The Answering Machine • Stanley Kubrick, "Tom Jones" and one point • Dickie Dickenson, David Lean and British Quota Film • Stanley, Joe and "2001: A Space Odyssey" • Takuo Miyagishima, Robert Gottschalk and a 20:1 Zoom • David Lean and The Friese-Greene Award • Thunderball, Zhivago, Techniscope, and Fogging a roll of film • Ken Annakin, "Grand Prix", James Bond, Helicopters • How lucky can you be More in 70mm reading: • The Importance of Panavision • A Message from Freddie A. Young • Stanley Kubrick • Shooting "Lawrence of Arabia" • Memories of Ryan's Daughter • Joe Dunton • Ken Annakin • 70mm in London 1958 - 2012 • The editor Receives BKSTS award |

The First To Rent Out Film | |

Sir

Sydney's parents, photographed in November 1946. Marjorie

Vint (1901–1989) and George Berthold "Bertie"

Samuelson (1889-1947). Private image Sir

Sydney's parents, photographed in November 1946. Marjorie

Vint (1901–1989) and George Berthold "Bertie"

Samuelson (1889-1947). Private imageAnd I think the records have it that the first person to rent out films in Britain was my father, who was known as Bertie, short for Berthold – GB Samuelson was his professional name. Now I mention all this because I was always in an environment of cinema. My parents always talked about cinema; my mother worked as an actress in films – she had a professional name, even. One of the few films of my father’s of which we have a complete copy is a drama called “She”, written by Rider Haggard, quite a famous English author. And for my father it was one of his last silent films. Made in Berlin, it was a German-British co-production, and I think the deal was probably that my father’s company provided the script, the actors, the crew, all the technicians – and the German partner supplied the studio, which was an old – sometimes we’re told it was an old tram garage, other times that it was where Zeppelins were built – but it was certainly in Berlin. The German partner probably supplied the craft grade people of the production crew. It was 1925. I know that, because we’ve got a production still of the whole crew and all the actors and actresses and, in the corner, are my mother and my father, the producer. I like to say that as it was in the middle of 1925 when that photo was taken, and as I was born in December 1925, I reckon I’m somewhere in that picture as well! |

Internet link: • George Berthold "Bertie" Samuelson (1889 - 1947) (PDF) • Samuelson Film Service (reunion) • samuelson.la • The Argus • British Film Industry Salute • Wikipedia YouTube/Vimeo • 'Strictly Sydney' • Clapper Board Part 1 • Clapper Board Part 2 • St. Mary's 1963 |

Talking Pictures | |

|

So that’s why I know the dates, but by the

time I was old enough to leave school, which was in 1939 – when I became 14

– my father had lost everything in his business life. The first disaster for my father was when, virtually overnight, talking pictures came in, and whatever capital my father possessed was in the form of some of the pictures he’d made, which became somewhat obsolete overnight. First there were only silent movies, and then "The Jazz Singer" came from Hollywood, complete with sound. After this, who wanted to see silent pictures anymore? And if your capital was tied up in a string of silent pictures, suddenly – your capital, whatever it was – was no longer there. That was the first time my father had a major financial disaster I think. Anyway, by the time I was fourteen, at the end of 1939, my elder brother had already left school, and I was ready to leave. I think a lot about 14-year olds today, like my grandchildren aged 14 – I consider them still to be children! | |

Hard Times for my Father | |

The

four Samuelson Brothers. L to R – Sydney, David, Tony,

Michael.

Private picture. The

four Samuelson Brothers. L to R – Sydney, David, Tony,

Michael.

Private picture. The fact that I was working in the local cinema when I was just 14 is, in today’s terms, an amazement to me. But at the time, my parents had no money. My mother ran a little shop and we all somehow survived out of it, but with difficulty. We just about managed with my father unable to get work of any kind. I explain the situation in that it would be like if, say, Richard Attenborough came on hard times and needed a job. Nobody would give him an ordinary job – how would you be able to say to Dickie Attenborough, “I could give you a job as a clerk in my distribution office”...you couldn’t do that. My father had had such senior positions, and was so respected (and had made over a hundred feature films) it was not that he was simply unemployed; he was unemployable! Nobody would give him a job. My father, if he could have managed to get a job earning – and I’m talking about the late ´30s – five pounds a week – he would have been so pleased to have five pounds a week coming in. As it was, my mother ran this shop six days a week, came home – her day off was Sunday, when she did all the laundry for the family of six because we were four brothers. And she did all the cleaning of the house on that one day. And my father used to look at her down on her knees scrubbing the floor in the kitchen. And there he was, once a great figure in our industry, unable to provide for his wife and children. And seeing his wife, his darling wife, on her knees scrubbing the floor. It was a very hard time for my father. So there was no question, as soon as my older brother, David, who’s 17 months older than I am – as soon as he was 14 he got a job. And as soon as I was 14, I too got a job. And I was lucky, because while I was still at school, in the latter part of 1939, they were building a new cinema in our little town which was called Lancing, on the South Coast of England – near Brighton, Sussex, if you know anywhere around there. I called in when they were still building, and managed to see, not the Manager, but the Managing Director, sort of the owner of this new cinema, called the Luxor, Lancing. And I said, “I just wondered, Sir, if you will be needing a boy in your projection box because I’ll be leaving school once I’m 14”. And he said, “When will you be 14?” And I said, “On December the 7th”. And he said, “Well we haven’t taken anybody on yet, it’s a bit too early. We’re not going to be opening until the end of the year – late December – we hope to open in time for Christmas. But I will speak to the Chief Projectionist, who is coming to us from the Plaza, Worthing”. The Plaza, Worthing, was about 3 miles away – part of a big circuit called ABC and it was their flagship cinema in Worthing, probably 15-, 16-, 1700 seats – a newish cinema, built in the mid-1930s. And the Chief had been attracted to come to be the Chief at the brand new, but smaller, cinema in Lancing – I think we were a thousand seats. Anyway, sure enough, I got that job, Rewind Boy at the Luxor Lancing. That answers your question – I’m afraid a bit of a long rigmarole! | |

Cinema was always in my Family | |

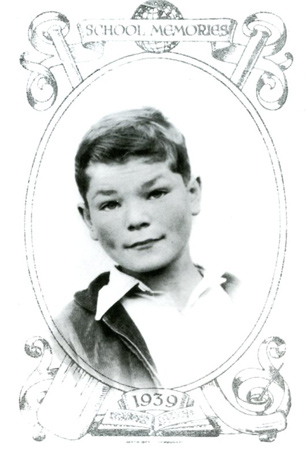

Sir

Sydney in 1939, age 13. Private image Sir

Sydney in 1939, age 13. Private imageBut Cinema was always in my family, in my mind. My parents always talked about films, although we actually hardly ever went to the cinema from when I was about 7 or 8, simply because my parents couldn’t afford it. They never went to the cinema, I never went to the cinema, my three brothers didn’t go to the cinema – we didn’t have the money. We were not an unhappy family; we were lucky, we were a close, loving family – but we’d no money. Anyway, perhaps I could just tell you a story – when "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" appeared – I think it was 1937 – it came to the other big cinema – the Odeon in Worthing, because Odeon released all the Disney product – and although there was a little Odeon cinema already in Lancing, my mother must have said to herself, “I’m not going to have my four being the only children in the school who have not seen "Snow White"”. Because when it came out, the first full-length cartoon, ever – and a very good movie as well – everybody wanted to see it. And so one Wednesday – because the shop by law had to close on one half day a week; it was called “early closing day” – it was the law to give the staff half a day off a week, because they worked on Saturdays; if they worked in a shop they had to work on Saturdays, so Wednesday afternoon and all day Sunday were their time off – so my mother, instead of doing household chores, or whatever it was, one Wednesday afternoon – early closing day in Shoreham-by-Sea, which is where my mother’s little shop was – she actually took us on the bus to Worthing to see "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs". And I remember every word of the following conversation – she went up to the box office and said to the girl, “One and four halves” (this was at about 2 o’clock in the afternoon – we call it the Matinée performance) and the girl in the box office said, “No half price for "Snow White"!” And do you know, Thomas, that made the difference between us going to see "Snow White" and not going to see "Snow White"! The best my mother could do – and I still think about it, the humiliation: how could that poor woman have felt – we were virtually in the cinema – to say, “No, we were not going, let’s see what is on at The Plaza”. And so we went, and because the disappointment was so momentous, I remember every item of the Plaza show. We went to see Robert Taylor and Wallace Beery in "Stand Up and Fight". The second feature, the “B” film, had a young comedy actress called Jane Withers and that was called (I think) "Always in Trouble". And we saw the Pathé News, also a black-and-white cartoon, and the trailer for the film “coming next week”. And the man came up on the Wurlitzer organ and played “Oh I do like to be beside the seaside”, because Worthing was a famous seaside resort and that was his signature tune. So if nothing else, Thomas, it’s an example of how impoverished we were. | |

Sir

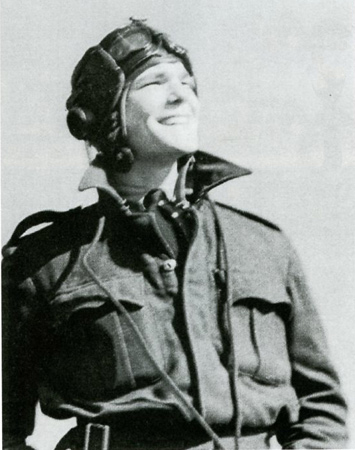

Sydney in the British air force. Private image Sir

Sydney in the British air force. Private imageMany years later, when Bob Gottschalk, the President of Panavision said, “While you’re over here Sydney, I want us to go to the Disney Studio; they are always asking me to have lunch”, and I thought, “I don’t like having lunch with them because they never use our lenses and cameras. They never use our gear because they’ve got all their own old stuff, and Disney doesn’t particularly like me, they never give us any business at all, and they’ve got all this out-of-date equipment which they insist on using”. I’m sure you know, Disney have their own studio at Burbank. So we went and had lunch there. Bob used to take me as – I know this will sound awful – as his kind of gentlemanly English friend...so unlike the rough and tough Hollywood people! [Laughs] I think that was why he used to like me go with him, and he would introduce me as the Panavision representative in Europe, and so on. Now we’re jumping on a little bit – but years and years after that, when I was the British Film Commissioner, I used to go regularly to Los Angeles because that was my job – to say to people like Spielberg, “I know you’re investigating and doing reconnaissances for a new picture...I believe it’s called "Saving Private Ryan"...and I know that you’re going to be looking for a location in Europe to reproduce the D-Day landings, and we’ve got the beaches that you can use for Normandy and we’ve got all the equipment you could ever want by way of cameras and everything else, and we’ve got the best technicians certainly in Europe, arguably in the world”. And that was really the job of British Film Commissioner – to promote the British film production sector. I met all the top production people from all the studios. I was sitting privately with the then Chief Exec at Disney, who happened to be an Anglophile (when I was later invited to have dinner in his home he had a flagpole outside, flying the Union Jack, he was that much of an Anglophile), and I was able to tell him about "Snow White" in Worthing all those years earlier. And I always remember because he said, “No half price for "Snow White"...My God!” It was for children, that film, but not for me, my mum and my brothers. I was trying to tell you how my interests came in cinema in the first place – now if I could just go back to my earliest days, at the Luxor Lancing. I did get the job, round about September 1939, when I was still at school, with about three more months to go until my 14th birthday. The British Parliament changed the law and they said, “14 is too young; children should be at school until they are 15”. And it was changed; as from January 1940, the school minimum school-leaving age would hence be 15. I was absolutely devastated! Because I wanted to leave school, not only because it would be more enjoyable - “It must be more lovely to be working in a cinema than to be sitting at school!” was how I thought, aged 13. But what happened was the War started in September (1939). And so they didn’t change the school leaving law – they left it at minimum age 14 because so many young fellows were being called up into the Army, Airforce, Navy and everything. I hate to say it, but it was probably the only good deed Hitler ever did! Certainly for me, because he enabled me to leave school when I was 14 instead of having to – as I probably thought – “waste another year”. | |

The Rewind Boy | |

|

So I went to the Luxor Lancing because the

Managing Director had interviewed me a few months earlier. But I remember

well a problem I had – a kind of a problem – it was that the Chief

Projectionist resented the fact that he wasn’t the one who’d interviewed

this boy and given him a job. He felt – and I now sort of understand it – he

felt that to select and hire the Rewind Boy was the job of the Chief

Projectionist and not of the Managing Director. So to him that didn’t make

me, as we say, the flavour of the month. I had some difficult times. And the

way I describe it is that I felt that my boss – Frank Chipperfield his name

was, with an impeccable reputation as a Chief Projectionist; he’d had the

top job in the area, at The Plaza Worthing – I felt that, in later years,

when I’d been much involved in the training of young people coming into our

industry, I felt that Frank Chipperfield seemed to believe that if he didn’t

make the boy cry at least once a week he was failing in his training

schedule! Not only that, for the first weeks – not days – weeks – I never

touched a frame of film, let alone rewind a reel of it. I only did cleaning

and polishing, making the tea, running errands, going and getting cigarettes

for the other projectionists. Eventually I was scheduled to actually begin

training as a rewind boy. Now there are many who will say, “Well isn’t it just – doing that, rewinding film from one spool to another?” But there was more to it than that, with this Chief. First of all, you had to do exactly that of course, but you had to run the film through thumb and first finger to identify any old joins that were coming undone, or any tears, or anything rough. You didn’t just rewind from one spool to the other. And you had to get used to holding one edge of the film, just one edge, against the inside of the spool flange, so that, on the other side, you could run your fingers down the reel to ensure it was absolutely flat, that there was no ridging, no risk one piece of film was sticking out halfway down the reel which could get bent over and tear at the sprocket holes. I was given a practice reel of film and it wasn’t until I could rewind it and deliver it for the Chief to inspect it that I was allowed to actually rewind. The films came in ten-minute reels (900 – 1000 feet), and we always joined them together in pairs. A spool for a projector was 2000ft; two ten-minute rolls joined together. You cut off the leader of Part Two and the end of Part One and joined them together. And a cement overlap join was made (as there were no plastic joiners in those days). So it was a very unhappy time for this lad, but I learned my standards as a projectionist from that man because he didn’t allow any mistakes. We used to show six feature films a week, because there were three different programmes. Each programme had a first and a second feature – Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday was one programme, Thursday, Friday, Saturday was another programme. On Sundays it was old films, usually very old copies as well. But they were like – what would you call them – nostalgic archive films, mostly not that old, but they would be films perhaps that people had enjoyed seeing years ago – such were the Sunday presentations at the Luxor. Anyway, my life was a bit of a misery. I remember one of my weekly jobs was to clean the floor in the battery room, a separate room with huge lead acid batteries for the emergency cinema lighting circuits. Next door were the two rectifiers for the projectors. They were all there, floors to be kept clean by me. There were also fumes wafting around, I suppose off those big batteries. I used to hide in there when I needed to have a cry! [Laughs] I would pull myself together and go back and get on with whatever I had to do. But that man Chipperfield, he taught me so much. I think for every new programme he used to sit in the back of the Circle with a notepad and note the sound levels on all the reel changeovers. Sometimes, in the film laboratory, the density of a new print would vary from reel to reel. The lab outputs were not necessarily consistent. I don’t think it was a problem with variable area sound, but it affected variable density tracks. And so Chief used to list if there was a change in sound level when they went say, from reels 1 and 2 to 3 and 4. He would make a note of that and would produce a cue sheet for every film that was shown. It would have from the end of Part 6 to the beginning of 7, “Up 2 points on the fader of the incoming machine”. He was that meticulous, and of course if he was sitting there, and there was a changeover and the incoming arc had not been accurately trimmed so the overall colour of the light varied – it was mostly black-and-white films so you’d notice whether it was a bit blue or a bit yellow; it would be a bit yellow if the carbon arcs were not trimmed properly – the Chief would go crazy and want to know how did it happen? He was a hard taskmaster. I think he came to feel that I wasn’t such a bad kid after all, and that was probably because I was an enthusiast – I was fascinated by the movies and the machines which showed them.  Sir

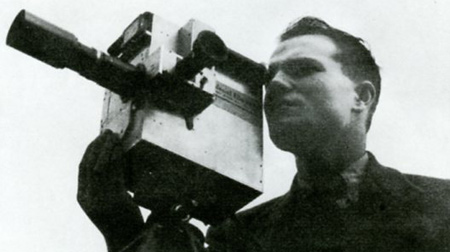

Sydney with a camera. Private image. Sir

Sydney with a camera. Private image.The law in those days was that if you were age 14 and working, you couldn’t work after 9 o’clock at night – you had to leave by 9 o’clock. So at 9, even though the main Feature would have just about started – the third and last running of the day – I would be dismissed. After I had delivered the first two parts of the main feature, and it would have been laced up, ready to go, usually around about 9 o’clock, I said farewell. But I would go and sit in the cinema and watch the main film every night. So I saw, probably, three main features and sometimes three “B” pictures every week! And so I got to know a bit about movies. I don’t think in those days I was ever aware of who the Cameraman was; I would know one or two Directors – every few months we would show a film by Alfred Hitchcock – I don’t think I knew probably the name of any Cameraman of any nationality in those days. Then, on my day off – I think it was Tuesday, so I could work on Sunday – I used to go on the bus all over Sussex – East Sussex, West Sussex, little bit into Hampshire, little bit into Surrey. And I used to go to the local cinemas and request at the box office, “Could you ask the Chief if he would let me see the ‘box?’” So the strange thing was that I knew all the projection equipment that there was around. Because I would go to a town like Brighton – it had magnificent newish cinemas – the Odeon, the Astoria was the big ABC house, and they had another big one as well, the Savoy, up the road – but they also had little cinemas, and some were what we call “fleapits” – does that expression mean anything to you? – Good! Because it describes them – maybe very old live theatres that had at sometime been made into cinemas. Nothing much done, except two projectors put in, plus a sound system and a screen. But I got to know all the makes well. I’ve always felt that the trouble with British projector manufacturers was their product was too good! They never wore out...the only things it seems to me one ever had to occasionally change were the sprockets and the exciter lamps. The intermittent sprockets, that had the hard work to do, their teeth used to wear down...and then you could hear that they were just catching the film and clicking a bit. You then had to change the intermittent – but that was about all! And so these very old fleapit cinemas still had the same projectors that had been put in when they first became cinemas. Some of them were the systems that had been put in when talkies – sound – came along in the late 1920s. Often installed was what was called the Western Electric Universal Base. It was a base that the sound people supplied to carry the projector, regardless of make. Western themselves made the sound – they didn’t make the projectors or the arc lamps, but they made the base that it was all assembled on. And they made the motor. The base had a disc player as well as their own “Wide Range” sound-on-film system - the discs for “talkies” were about 18 inches diameter. It was big. They designed the soundhead, photo-electric cell and so on, and some of those projectors, on the original Western Electric bases, were still there...but then I thought, “They’re so ancient, yet they’re still using that equipment”. But I’m talking about when I started working and going around to look at other people’s gear. That was 1940. Talkies came out in 1928, so that was only 12 years before. In my childlike imagination it was as if it were 50 years ago that they’d had installed those projectors, but it was really only 12 years earlier since talkies had come in, before the period I’m talking about. And why I remember them, the Western Electric bases, so well – it was a fine piece of engineering, with its dual sound system, because at first some talkies were “sound-on-disc”. Then, particularly from Fox – their sound process was called Fox Movietone and they were only sound-on-film, variable density – but a cinema had to be able to play sound-on-disc or sound-on-film – they didn’t know till they got the copy from the distributor whether the print also had a box of discs with it, or whether the sound would be on a track on the same piece of film as the picture! And so they had to have the dual sound system, but not for very long, because the disc sound system was so unsatisfactory. I never worked with sound-on-disc – but when you think of it, sound-on-film, if you have a break, you lose two frames when you’re doing a cement overlap join – you had to take the two ends, scrape the emulsion off one of them, add acetone and put them together, so you lost at least two frames. When you think of it, every time you joined the end of Part One onto the beginning of Part Two, you lost two frames! And then, when you were sending the film back after you’d finished with it, you lost two more frames! One from the end, and one from the beginning, so every time it went to a cinema, two frames were lost, which meant a total of four frames, and so the sound jumped, and the picture jumped! And the older the copy was, the worse it was! So that was one thing, but it was much worse with disc, and that is, if you got a break in your picture, and your sound was on disc, OK, you could cut the break out and do a cement join. There’d be a tiny picture jump at first, and if you had to re-do the join there’d be a bigger jump. But how do you remove the equivalent amount of sound from the disc? You can’t – so they used to have to put black spacing into the film to make up the fact that the disc would be the same length, even though you were cutting bits of film out all the time. You were supposed to – if you cut out two frames, you had to compensate with two black frames in – imagine! You’re watching the film and two black frames – what’s that, a twelfth of a second – doesn’t sound like much, but you can see a twelfth of a second. So it must have been that the quicker they could get rid of discs and go completely onto sound-on-film, the better. So I don’t think discs were in place for more than a couple of years, if that, and I should think if the film was any good, once sound-on-film was available they would do a new copy with sound-on-film and throw away the discs because they were so difficult. And I think the actual sound quality was terrible as well. Of course, if somebody bumped into the pick-up arm, you could never find the place! [Laughs] You know, there was nothing you could do to get back into sync; it was a terrible system. | |

Bertie

Samuelson, Sir Sydney's

father. Private image Bertie

Samuelson, Sir Sydney's

father. Private imageHowever, there was a hangover for me in that when my father eventually got work, it was up in the Midlands. It was an awful job – what had happened was that all the distributors’ Birmingham branches, with all the copies of all their films, were all on nitrate stock. And so the Fire Department in the City of Birmingham said, “We don’t care what you do, but if one incendiary hits John Bright Street (the street that more or less had all the distributors’ places in it – like Wardour Street in London), if one incendiary hits one stock of films, if it hits Paramount, the whole street will go! So you’ve got to get out”. So all except Warner Bros. and MGM, who made their own arrangements in their own disused country houses out in the country, in the suburbs of Birmingham, all the other distributors took one great big old house in a place between Birmingham and Walsall. And all the distributors moved in, some of them put up temporary buildings to store their copies. And then, on the main changeover day, which was Sunday morning – because every cinema changed their programme after Saturday night; whether they showed their film for a week or only three days it always ended on Saturday night – all the films used to be collected during the night and taken to this “film dump” as it was called, where, if I can just suggest, you only have to think of the shortage of manpower during the war, what kind of characters from the social community were left to man the film dumps, humping these great cans of film and loading them onto trucks: what kind of women were there left, who weren’t working in factories making shells and tanks, armoured cars, things like that – what type of women were left to be doing the repairs of the old, and older, copies of films, which were all kept at the film dump as well? You had – I know it sounds awful – the lowest level members of the community working at the film dumps and therefore what was going on doesn’t even bear speaking about, what with the fighting of the men and the behaviour of the men to the women. In the end, the KRS – the Kinematograph Renters’ Society – had to do something about it. So they had to appoint a Supervisor...and that was the job that my Dad got. It didn’t pay very much, but it did two things: it meant at least he was self-sufficient, and that included the fact that as he had always been an employer, he had no State benefits – he had no dole (“dole” is a government payment when you’re out of work – we call it “being on the dole”). There was nothing – he had no right to any dole because he’d always been an employer and therefore had not paid his weekly amount of what we call National Insurance, which was where the dole money came from, and he was severely diabetic and his insulin had to be bought. So at least this awful job in the Midlands meant that he was not a financial drag on his beloved wife and, also, it enabled the shop, which had been getting into financial difficulties – because the South Coast had been a defence area – any time the Germans were expected to invade, the result of that was you could move out of that area and go and live somewhere else, but you couldn’t move into it – the government, the war office, whoever it was, they didn’t want civilians down there – they would have cleared it all out of civilians altogether if they could have done, but where would they put everybody? – it enabled the shop not to close down. | |

|

• Go to next chapter:

Panavision, Bob

Gottschalk and The Answering Machine • Go to previous chapter: A Conversation with Sir Sydney Samuelson • Go to full text: Sir Sydney Samuelson and Real Picture Quality • Go to home page: A Conversation with Sir Sydney Samuelson | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 21-01-24 |