Liner notes for "The Wonderful World of Brothers Grimm" 2-CD soundtrack | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Jim Lochner | Date: 30.04.2010 |

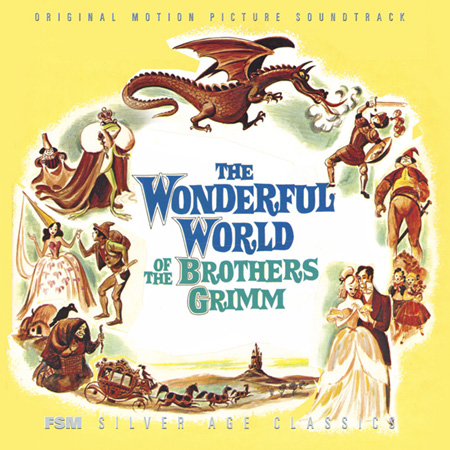

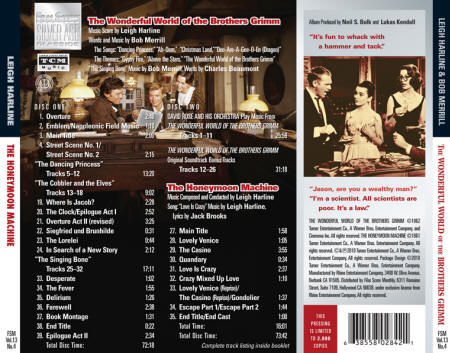

"The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm" "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm"The following article was written as "online liner notes" for Film Score Monthly's first-ever CD release of the original soundtrack recording to "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm". It is reprinted here with permission. For more information and sound clips on the CD-and to buy a copy-please see Film Score Monthly Once upon a time, Hollywood panicked due to the new phenomenon known as television. Between 1949 and 1952, the number of television sets in the country rose from 950,000 to 11 million. At the same time, attendance at the movies dropped sharply, from 90 million a week in 1948 to 56 million in 1952. Just as Hollywood was looking for a new way to entice moviegoers into theaters, along came Cinerama. The new Cinerama process mounted three camera magazines as one. Its 27-millimeter lenses, which filmed three separate images with a single shutter, together possessed the same focal length as the human eye and curved at the same radius as the retina. Projecting those three images onto a mammoth, 146-degree louvered screen formed one giant picture. Cinerama was the brainchild of Hollywood special effects technician Fred Waller (1886–1954), perhaps better known for his invention of modern water skis. Cinerama grew out of Vitarama, an even more cumbersome 11-camera system designed for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, in which the cameras created a single image on a huge domed screen. In 1941, Waller received a government contract to use Viterama to shoot training films for aircraft gunners. By the end of World War II, an estimated one million soldiers had practiced on the Waller Gunnery Trainers. Despite backing from Laurance Rockefeller and Henry Luce during the 1940s, Cinerama did not get off the ground until well-known adventurer and radio newscaster Lowell Thomas and legendary Broadway showman Mike Todd came on board in 1950. Along with Merian C. Cooper (King Kong), Thomas and Todd produced the first Cinerama feature: This Is Cinerama. The film, which premiered on September 30, 1952, at New York’s Broadway Theatre, opened with a heart-stopping rollercoaster ride that thrilled audiences. As a travelogue, the film showed off the camera’s unique capabilities with splendid vistas of the Grand Canyon, a gondola ride in Venice, and a production of the Act II finale from Verdi’s Aida at La Scala. A Cinerama showing was an event. Each ticket holder received a specific seat number, audience members dressed up, and the theater did not sell concessions. A sound mixer ran the board for the seven-track stereophonic sound system designed by Hazard Reeves, adjusting the levels for each individual performance. The result was an experience that, according to publicity materials, “could literally wrap the world around a theater seat.” Over the next several years, Cinerama films delighted audiences with their unique cinematic experiences, whether riding the rapids or flying over the mouth of an active volcano. Each successive travelogue, however, saw diminishing returns at the box office. Now the time came to use Cinerama to tell a dramatic story. | More in 70mm reading: "The Wonderful World of Brothers Grimm" soundtrack released by Film Score Monthly Cinerama Film Internet link: Film Score Monthly Screen Archives Entertainment Brothers Grimm Liner notes Liner notes reprinted with permission from Lukas Kendall, Film Score Monthly The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm Music Score by Leigh Harline Words and Music by Bob Merrill DISC ONE Overture 2:46 Emblem/Napoleonic Field Music 1:19 Main Title 2:00 Street Scene No. 1/Street Scene No. 2 2:15 “The Dancing Princess” Once Upon a Time 2:51 Pursuit 1:34 Gypsy Rhapsody 3:02 Gypsy Camp Bridge/Princess Waltz (Dream Sequence) 1:30 Remembrance 1:00 The Tumbler 0:46 The Bridge 1:11 Dancing Princess 1:09 “The Cobbler and the Elves” Once Upon a Second Time 0:57 The Old Cobbler/Christmas Land 1:30 Go Home 0:40 Ah-Oom 2:36 Good Luck Elves 1:29 The Old Cobbler/Christmas Land 1:39 Where Is Jacob? 2:28 The Clock/Epilogue Act I 2:52 Overture Act II (Revised) 3:25 Siegfried und Brunnhilde 0:31 The Lorelei 0:44 In Search of a New Story 2:12 |

.jpg) In 1958, Cinerama teamed up with M-G-M to produce dramatic motion

pictures. As part of this unique agreement, both studios would share

equally in the production costs as well as the profits. But, as Roger

Mayer, president of Turner Entertainment, pointed out in the documentary

Cinerama Adventure, “It was considered a tremendous risk.” Within weeks

of the announcement, Cinerama packed up more than $3 million in cameras

and special equipment, moving its offices from Oyster Bay, New York, to

the Forum Theater in Los Angeles, redesigning that facility and

equipping it as a research center aimed at perfecting proven Cinerama

techniques and developing new ones. Nicholas Reisini, president of

Cinerama, “felt very strongly that the venue—the Cinerama

process—deserved tremendous theatrical productions, lots of stars,

tremendous vistas,” as Reisini’s son Andrew recalled in Cinerama

Adventure. How the West Was Won went into production first (“For the

First Time Cinerama Tells a Story!” trumpeted ads), but when it fell

behind schedule, another picture became the first Cinerama feature to

reach theaters. In 1958, Cinerama teamed up with M-G-M to produce dramatic motion

pictures. As part of this unique agreement, both studios would share

equally in the production costs as well as the profits. But, as Roger

Mayer, president of Turner Entertainment, pointed out in the documentary

Cinerama Adventure, “It was considered a tremendous risk.” Within weeks

of the announcement, Cinerama packed up more than $3 million in cameras

and special equipment, moving its offices from Oyster Bay, New York, to

the Forum Theater in Los Angeles, redesigning that facility and

equipping it as a research center aimed at perfecting proven Cinerama

techniques and developing new ones. Nicholas Reisini, president of

Cinerama, “felt very strongly that the venue—the Cinerama

process—deserved tremendous theatrical productions, lots of stars,

tremendous vistas,” as Reisini’s son Andrew recalled in Cinerama

Adventure. How the West Was Won went into production first (“For the

First Time Cinerama Tells a Story!” trumpeted ads), but when it fell

behind schedule, another picture became the first Cinerama feature to

reach theaters.The Grimm brothers, Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), achieved recognition in their day as scholars of German and Serbian grammar, legal antiquities and Latin poetry. But their collections of over 200 fairy tales ensured their place in history, with characters like Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella and Tom Thumb enchanting generation after generation of children. Over the years, the Grimm fairy tales found great success on screen, but before 1962 no film had ever told the story of the brothers themselves. The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm was a pet project of producer George Pal (1908–1980), better known for such sci-fi/fantasy films as Destination Moon (1950, the first Technicolor picture dealing with a science fiction subject), When Worlds Collide (1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), tom thumb (1958), The Time Machine (1960, FSMCD Vol. 8, No. 13) and The Power (FSM Box 04). In 1956, Pal purchased the screen rights to Die Brüder Grimm, a collection of letters edited by Dr. Hermann Gerstner. As co-director Henry Levin would remark in the film’s press materials, “[Pal] felt their story needed telling more than their stories needed retelling on the screen.” Pal shopped his Grimm project to M-G-M, but studio chief Sol Siegel turned it down repeatedly. When Cinerama initiated its collaboration with Siegel and M-G-M, Nicholas Reisini—a fan of the Grimm stories—helped to reverse Pal’s fortunes. In Gail Morgan Hickman’s The Films of George Pal, the producer reminisced that when Siegel suggested filming Brothers Grimm in Cinerama, “I practically fainted!” The film opens with Jacob (Karl Boehm) and Wilhelm (Laurence Harvey) researching the family history of a local duke (Oscar Homolka). The siblings live together along with Wilhelm’s wife (Claire Bloom) and children. When the duke discovers that Wilhelm spends more time writing stories than on his assigned task, he gives the brothers two days to complete the project or face debtor’s prison. After Wilhelm loses the manuscript, Jacob leaves him to work on his own. The angry duke demands six months’ back rent on the Grimms’ lodgings and the strain sends a sick and feverish Wilhelm to bed. When he recovers, a penitent Jacob promises to stay and complete their work, much to the dismay of his fiancée (Barbara Eden), who refuses to wait for him. The film closes with the brothers’ induction into the Berlin Royal Academy. |

“The Singing Bone” Dee-Are-A-Gee-O-En (Dragon) 1:40 Entering Cave 1:59 Introducing the Dragon/Sir Ludwig the Brave 4:21 Dragon Dance/The Swinger/Ride Him, Hans/Death in the Cave 4:03 Braggart/Murderous Knight 1:09 The Seasons/Singing Bone/Decision 1:34 Singing Bone Part 2 0:39 Life Again/Sir Hans 1:31 Desperate 1:02 The Fever 1:55 Delirium 1:26 Farewell 2:38 Book Montage 1:31 End Title 0:22 Epilogue Act II 2:34 Total Disc Time: 72:18 |

Dramatizations of three of the Grimm fairy tales—“The Dancing Princess,”

“The Cobbler and the Elves” and “The Singing Bone”—beef up this rather

slim plotline. “The Dancing Princess” stars Russ Tamblyn as a woodsman

who, in order to win the hand of a princess (Yvette Mimieux) and half

the kingdom, must discover the secret location she travels to every

night and the reason that all her shoes have holes in them the next

morning. In “The Cobbler and the Elves,” Laurence Harvey plays an old

cobbler who receives a Christmas miracle from a quintet of magical

wooden elves. “The Singing Bone” stars Terry-Thomas as a cowardly knight

and Buddy Hackett as his faithful servant on a quest to slay a dragon

for fame and fortune. (The filmmakers had originally slated six fairy

tales for the film, including “Cinderella” and “The Fisherman and His

Wife,” the latter for no other reason than to show off a new Cinerama

underwater process that would take the audience on a tour through the

coral forests off Key West.) David Harmon freely adapted the stories

from their original sources and co-wrote the script with Charles

Beaumont and William Roberts. Dramatizations of three of the Grimm fairy tales—“The Dancing Princess,”

“The Cobbler and the Elves” and “The Singing Bone”—beef up this rather

slim plotline. “The Dancing Princess” stars Russ Tamblyn as a woodsman

who, in order to win the hand of a princess (Yvette Mimieux) and half

the kingdom, must discover the secret location she travels to every

night and the reason that all her shoes have holes in them the next

morning. In “The Cobbler and the Elves,” Laurence Harvey plays an old

cobbler who receives a Christmas miracle from a quintet of magical

wooden elves. “The Singing Bone” stars Terry-Thomas as a cowardly knight

and Buddy Hackett as his faithful servant on a quest to slay a dragon

for fame and fortune. (The filmmakers had originally slated six fairy

tales for the film, including “Cinderella” and “The Fisherman and His

Wife,” the latter for no other reason than to show off a new Cinerama

underwater process that would take the audience on a tour through the

coral forests off Key West.) David Harmon freely adapted the stories

from their original sources and co-wrote the script with Charles

Beaumont and William Roberts.“There was a big problem with Cinerama,” Pal told Gail Hickman. “No director wanted to touch it.…It was just too big.” George Stevens, Fred Zinnemann and William Wyler all turned down the project. After a successful screen test, Siegel assigned the directing chores to Pal, who quickly realized there were too many logistical problems to allow him to direct it all. Reserving the fairy-tale segments for himself, he hired Henry Levin (Journey to the Center of the Earth) to direct the remaining scenes. Pal wanted to cast Peter Sellers and Alec Guinness as the brothers but, according to Hickman, M-G-M did not like Sellers. “We need an all-star cast for the picture, but it wouldn’t be feasible the way things are now,” Pal diplomatically told The Hollywood Reporter. “What I intend to do is get young people of star quality and use them instead of ‘names.’” Pal sought advice from Ed Sullivan and Steve Allen, but M-G-M already had Laurence Harvey and Karl Boehm under contract. Pal originally intended the two leads to play major roles in all of the fairy tales as well, but ultimately only Harvey played one such role, as the cobbler in “The Cobbler and the Elves.” Scouting locations from Yellowstone to Yosemite, and a number of sites in Switzerland, Asia and India, Pal decided to shoot as much of the film as possible in the Grimms’ homeland—the Rhine River Valley and Bavaria—for authenticity and Old World charm. Because World War II had destroyed the Grimms’ birthplace—since rebuilt as a modern city—filming instead took place instead in two tiny Bavarian villages: Rothenburg ob der Tauber and Dinkelsbuehl, near Munich. Rothenburg ob der Tauber also sustained damage during the war, but city leaders had restored it to its original form in hopes of attracting tourists. German officials made two prominent landmarks available for the first time to a film company: Weikersheim Castle for the duke’s residence and Neuschwanstein Castle (commissioned by Emperor Ludwig II of Bavaria as a retreat for Richard Wagner) as the royal palace in “The Dancing Princess.” Neuschwanstein later appeared in The Great Escape, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Spaceballs. In addition, George W. Davis and Edward Carfagno (an Oscar winner for Ben-Hur) created more than 75 sets. Without recognizable stars, Pal fortified the film with “a lot of tricks” and sold the film based on its subject. Project Unlimited, which had handled the effects for Pal on The Time Machine, created most of the special effects. “The Cobbler and the Elves” starred Pal’s popular Puppetoons, a combination of puppet and cartoon, which had debuted as a dancing box of cigarettes in an advertisement in Europe during the 1930s. When Pal and his wife fled the Nazis and headed for Hollywood, he gave new life to the Puppetoons at Paramount with a series of animated shorts, including John Henry and the Inky-Poo (1946) and Tubby the Tuba (1947). The Puppetoons made their feature debut in The Great Rupert (1950) and featured prominently in tom thumb (1958). Wah Chang of Project Unlimited designed the elves, as well as a bejeweled dragon for “The Singing Bone.” The elf animation by David Pal (George’s son) and Don Sahlin took four months to complete, as did the animation of the dragon. Jim Danforth, who had worked with Pal on The Time Machine and Atlantis: The Lost Continent, handled the dragon special effects. |

DISC TWO David Rose and His Orchestra Play Music From The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm The Theme From The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm 1:54 Above the Stars 2:30 Ah-Oom 1:39 The Dancing Princess 2:19 Gypsy Fire 2:07 …and Other Motion Picture Favorites Till There Was You 1:59 Ebb Tide 2:39 Around the World in Eighty Days 3:13 Spellbound Concerto 2:30 Thank Heaven for Little Girls 1:52 Exodus 2:50 Total Time: 25:59 The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm Original Soundtrack Bonus Tracks Ah-Oom (with lead-in dialogue) 4:05 Dee-Are-A-Gee-O-En (Dragon) (with lead-in dialogue) 1:49 Emblem (alternate) 0:26 Main Title (alternate) 2:09 Princess Waltz (Dream Sequence) (alternate) 1:37 The Clock/Epilogue Act I (alternates) 2:52 Overture Act II (alternate) 3:25 Singing Bone (unprocessed) 0:43 Book Montage (alternate, with trombones) 1:30 Dancing Princess (solo zither) 2:35 Ah-Oom (pre-recording) 2:40 Dancing Princess (pre-recording) 1:13 Gypsy Rhapsody (pre-recording) 2:41 Princess Waltz (Dream Sequence) (pre-recording) 1:43 Dee-Are-A-Gee-O-En (Dragon) (pre-recording) 1:17 Total Time: 31:18 |

“The directors were under orders to really make attempts to show off the

[Cinerama] process,” recalled Andrew Reisini. “All kinds of stunts and

camera angles were to be employed by these directors in order to show

the audience what this tremendous process was capable of.” “Each of the

directors had problems with the format,” added Roger Mayer. “They were

not used to it, it was different, the size of the cameras, the

complexity of them, the fact that there were three pieces of film going

at the same time bothered all of them. And they were certainly not used

to composing the action to the camera’s problems rather than to what

they saw as the flow of the picture.” “The directors were under orders to really make attempts to show off the

[Cinerama] process,” recalled Andrew Reisini. “All kinds of stunts and

camera angles were to be employed by these directors in order to show

the audience what this tremendous process was capable of.” “Each of the

directors had problems with the format,” added Roger Mayer. “They were

not used to it, it was different, the size of the cameras, the

complexity of them, the fact that there were three pieces of film going

at the same time bothered all of them. And they were certainly not used

to composing the action to the camera’s problems rather than to what

they saw as the flow of the picture.”It was up to Oscar-winning cinematographer Paul Vogel (Battleground) to implement those stunts and techniques. In “The Dancing Princess,” in a scene meant to capture the thrill of the opening rollercoaster ride in This Is Cinerama, Vogel strapped the camera upside down beneath a stagecoach so that it could evoke the speed of horses galloping along perilous, winding dirt roads. The filmmakers also placed it in a drum to simulate the woodsman’s tumbling, gyrating vision as he rolls down a hill. In “The Singing Bone,” they attached it to a swing that sailed back and forth and round and around to simulate Buddy Hackett swinging above the snapping jaws of the dragon. In the old Bavarian villages, they mounted the unwieldy camera on a sled to absorb the shock caused by the uneven cobblestoned streets. For one scene, it became necessary to tear up part of an ancient thoroughfare. At first city officials balked, but they finally granted permission when Pal agreed to have each cobblestone numbered and replaced exactly in its original position. For Brothers Grimm, a new Cinerama challenge arose: filming the actors. “One of the main qualities of filmmaking and storytelling is the ability to do a close-up,” said Russ Tamblyn in Cinerama Adventure. “And, of course, in Cinerama you can’t really do a close-up. You can come in on somebody’s head. But even when you’re in tight on their head, you’ve still got two empty panels…the eye will go off to see what’s in those panels and you better have something out there.” Songwriter Bob Merrill composed the songs and the major themes for the film’s musical score. Merrill (1921–1998) began his songwriting career writing novelty tunes such as 1950’s “If I’d Known You Were Comin’, I’d’ve Baked a Cake,” followed by popular hits like “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window?” and “Mambo Italiano.” Before achieving fame as a songwriter, Merrill took a job as a dialogue director with Columbia Pictures, where he stayed for seven years. As an actor, Merrill appeared in The Story of G.I. Joe (1945) and, in his own words, “a dozen B films and westerns.” Further adventures in film included the lyrics to the classic “I’ve Written a Letter to Daddy” from What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), and the screenplays for Mahogany (1975), W.C. Fields and Me (1976) and Chu Chu and the Philly Flash (1981). Merrill’s television credits include lyrics (to music by Jule Styne) for two seasonal specials: Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol (1962) and The Dangerous Christmas of Red Riding Hood (1965), which starred Liza Minnelli. Merrill found his greatest success on the stage, writing music and lyrics to New Girl in Town (1958) and Take Me Along (1960)—popular musical adaptations of the Eugene O’Neill plays Anna Christie and Ah, Wilderness!, respectively. At the time of his work on Grimm, Merrill was still riding high from the success of Carnival, a musical adaptation of the 1953 film Lili (FSM Vol. 8, No. 15). In 1964, Merrill teamed with Styne to write the lyrics for the smash hit Funny Girl, his last and biggest success. His musicalization of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1966) never officially opened, and Henry, Sweet Henry, an adaptation of The World of Henry Orient (FSM Vol. 4, No. 16), only ran for two months. Although he reteamed with Styne for Sugar (1972), a musical adaptation of Some Like It Hot that enjoyed a respectable run of 505 performances, their final show, the ill-fated adaptation of The Red Shoes (1994), lasted only four days. The Songwriters Hall of Fame inducted Merrill in 1987. After a series of health problems, he committed suicide on February 17, 1998. For Brothers Grimm, Merrill wrote five songs for the fairy-tale segments and three instrumental themes for the underscore, including the sunny main theme. Like Irving Berlin and Noël Coward, Merrill could not read or write music. Instead, he composed by tapping out his melodies on a toy xylophone with letters marked on each key. Merrill would write the letters on paper, and then an assistant would turn them into proper musical notation. For Brothers Grimm, Leigh Harline adapted and arranged Merrill’s song melodies and themes into a proper score, assisted by orchestrators Gus Levene, Leo Arnaud and Herbert Spencer. |

The Honeymoon Machine Music Composed and Conducted by Leigh Harline Song: “Love Is Crazy” Music by Leigh Harline, Lyrics by Jack Brooks Main Title 1:58 Lovely Venice 1:05 The Casino 3:55 Quandary 0:34 Love Is Crazy 2:37 Crazy Mixed Up Love 1:10 Lovely Venice (Reprise)/The Casino (Reprise)/Gondolier 1:37 Escape Part 1/Escape Part 2 1:44 End Title/End Cast 1:00 Total Time: 16:01 Total Disc Time: 73:42 |

Harline (1907–1969) got his start in film in 1933 at Walt Disney

Studios, where he scored more than 50 animated shorts, including

installments in the Silly Symphonies series. Today he is best known for

his songs from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and his Oscar-winning

score for Pinocchio, which included the classic “When You Wish Upon a

Star.” After Harline left Disney in 1941, he forged a successful

freelance career, composing scores for nearly every major studio, but

particularly RKO and Twentieth Century-Fox. In the early 1960s, he

landed at M-G-M for three assignments: The Honeymoon Machine, The

Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and the delightful George Pal

western-fantasy, 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964, FSMCD Vol. 9, No. 11). During

the ’60s, Harline freelanced in television, including on the M-G-M

western series The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters. He died on December 10,

1969. Harline (1907–1969) got his start in film in 1933 at Walt Disney

Studios, where he scored more than 50 animated shorts, including

installments in the Silly Symphonies series. Today he is best known for

his songs from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and his Oscar-winning

score for Pinocchio, which included the classic “When You Wish Upon a

Star.” After Harline left Disney in 1941, he forged a successful

freelance career, composing scores for nearly every major studio, but

particularly RKO and Twentieth Century-Fox. In the early 1960s, he

landed at M-G-M for three assignments: The Honeymoon Machine, The

Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and the delightful George Pal

western-fantasy, 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964, FSMCD Vol. 9, No. 11). During

the ’60s, Harline freelanced in television, including on the M-G-M

western series The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters. He died on December 10,

1969.Harline recorded his Brothers Grimm score over 16 sessions beginning in December 1961 and stretching as late as July 17, 1962, three days after the film’s preview in Denver. To accommodate roadshow engagements, the score includes an overture, an entr’acte (“Overture Act II”) and exit music. Harline often assigns the main “Wonderful World” theme to zither, played by “zither stylist and Capitol recording Star” Ruth Welcome. Marketed as “the only woman in America to play the zither professionally,” she had learned the instrument as a child in Freiburg in the Black Forest of Germany. Although Welcome recorded 18 albums for Capitol Records, she is virtually unknown today. Also appearing as musical guests on the memorable “Ah-Oom” in “The Cobbler and the Elves” were yodeler Adolf Hurtenstein and the barbershop quartet The Mellomen—counting Bill Lee and Thurl Ravenscroft as members, the group sang backup for such diverse artists as Bing Crosby, Doris Day and Elvis Presley, as well as performing in numerous Disney features and shorts. Popular stars of the day covered several of Merrill’s tunes as singles. Lawrence Welk, Don Costa and clarinetist Acker Bilk each recorded “Above the Stars” while “Theme From The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm” became a hit single for David Rose, and again for Costa and Welk. Dick Manning and his orchestra recorded “The Dancing Princess,” while Merrill himself joined forces with a children’s chorus for “Ah-Oom” and “Theme From The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm” on the Kami label. Hansen Music Publishing printed dance and concert band versions of “Theme From The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm,” as well as piano/guitar/vocal arrangements of “Ah-Oom,” “Above the Stars” and “The Dancing Princess.” M-G-M pulled out all the stops in their efforts to publicize the film, advising theater owners to “set up [a] loudspeaker system in front of the theatre and play the songs from the film during the engagement. This will capture the interest of shoppers and passersby.” The publicity department also: provided suggestions for radio campaigns in which children could have “fairy-tale” sessions on the air, reading from the popular Grimm stories; encouraged children to dress in traditional Bavarian costumes; and suggested that newspaper food columnists “discuss the delicious foods of Bavaria and Central Europe.” Claire Bloom offered “mouth-watering German cooking recipes” and Yvette Mimieux provided sage advice in “Yvette’s Beauty Tips for Teen-Agers.” The “Gypsy Fire” sequence even figured in a promotion for a program called “Dancing Away Those Surplus Pounds!” The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm previewed on July 14, 1962, at the Cooper Theatre in Denver, its spherical 800-seat auditorium the first in the world built specifically to accommodate Cinerama films. Advance tickets for individuals and theater parties went on sale one month prior to the picture’s official opening on August 8. (The studio moved up the film’s premiere from its original 1964 date in part to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the earliest edition of the Grimm tales.) The film premiered in a roadshow version at premium prices in New York, Los Angeles and 12 other cities, with another nine engagements scheduled to open over the following three weeks. “The Cinerama process has come of age as a dramatic tool,” proclaimed Variety. “[Pal] has created an enchanting world…a trailblazer in the annals of motion picture history, commercially and artistically.” “There’s a wonderfully new and exciting movie entertainment in town, bubbling over with fun and frolic for young and old,” said Cue. “But the key to the picture is the wonder, the magic, the songs, and the fun—and all are here. When the biographical drama falters (as it does from time to time) the fairy tales take over and they are a delight.” Other critics also had reservations about the script. “The story, now that Cinerama has at last got around to telling one, seems hardly worth telling,” said Time. “Furthermore, the film’s interpretations of the tales, though amusing, incline to be cute and design to be sentimental.” “[The] surrounding story of the two brothers,” said The New York Times, “one expansively played by a leaping and laughing Laurence Harvey and the other played flatly by Karl Boehm, is much too long and academic.” “If the Grimms had never told better stories than these,” wrote the New York Post, “they would not have had a tenth of their fame.…In some curious ways these episodes water down the story of the Brothers Grimm.” The Post complained further that Harvey, who would receive a Golden Globe nomination for his performance, played Wilhelm “as if he considered himself in competition with the greatest, most theatrical hams of his era.” Even after 10 years, critics still had reservations with the Cinerama process itself. “If anything, this story is inhibited and constrained by the evident photographic rather than cinematic emphasis that the process impels,” wrote Bosley Crowther in The New York Times. “As a consequence, a simple little drama…is rendered dramatically tedious, although it is pictorially rich, with a lot of eye-filling shots of country and ancient German castles and towns.” “It seems a pity,” said the New York Herald, “that the promise of the process is not fully realized, that a really good fairy hasn’t come along to make the seams disappear between the panels of the monumental triptych, and put an end to the jiggling and the distortion.” The Cinerama process, wrote Time, “still full of half-squashed bugs, presents at least one insoluble problem: a moviegoer watching a screen the size of a tennis court can quite readily get a stiff neck from trying to follow the conversational ball.” Saturday Review summed it up: “Wonderful World is a beginning, little more.” | |

Click

image to see enlarged version Click

image to see enlarged versionOnly a handful of critics bothered to mention the music. Daily Variety and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner pointed out the “significant contributions” of the score, while Saturday Review called the music “pleasant and unmemorable.” Cue was a bit more appreciative: “Not the least of the film’s pleasures, are the whistleable, toe-tapping songs by Bob Merrill.” The Hollywood Reporter took pains to credit both composers, complimenting the “several catchy songs by Bob Merrill, integrated in a score of atmosphere and excitement by Leigh Harline.” On the negative side, The New Yorker called the film a “third-rate Hollywood musical” and a “nightmare.” The film received four Academy Award nominations, with Mary Wills winning for Costume Design, which the film’s publicity materials bragged “ran the gamut in fabrics from homespuns to 14 karat gold cloth,” in addition to Terry-Thomas’s 40-pound suit of armor and nearly 1,500 other costumes. The other nominations came in the categories of Color Art Direction, Color Cinematography and Scoring of Music—Adaptation or Treatment (in which Harline lost to Ray Heindorf for The Music Man). The music branch also shortlisted Harline’s score for “Music Score—Substantially Original.” In its review of the film, The Hollywood Reporter predicted, “Cinerama is here to stay as firmly as any other development in motion pictures over the years, a solid part of production and an important one for Hollywood.” Encouraged by the “continuing prospect of real movies made for the wall-to-wall screen and shown at ear-to-ear prices,” reported Time, “dozens of key theaters are currently converting to the system—at a cost that ranges from $175,000 to $500,000 a theater. By year’s end, 60 of them will be open in the U.S. and some 40 more in other countries.” It proved difficult, however, to construct the theaters and expensive to convert existing venues to exhibit Cinerama. In addition, operating costs devoured more than half of the weekly revenues that came in from the Cinerama films. “I think finally that additional features were not done in Cinerama not because the results were not satisfactory,” said Roger Mayer, “but that it became too difficult and restricting as a distribution matter.” Brothers Grimm pulled in a paltry $4.8 million in rentals—far below the $15 million earned by This Is Cinerama a decade earlier. How the West Was Won took in $20 million the following year, but the M-G-M/Cinerama partnership did not live happily ever after. Even with the success of How the West Was Won, Reisini and Cinerama experienced financial problems. In 1964, one of Cinerama’s major exhibitors, William Forman, owner of the Pacific Theaters chain, came forward and took over control of the company, then began to use Cinerama as a distributor rather than a production format. How the West Was Won was the final film in the three-strip Cinerama process. Later pictures marketed as Cinerama releases—It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, The Greatest Story Ever Told, Khartoum, Grand Prix and 2001: A Space Odyssey—were actually 70-millimeter, single-lens productions. Ironically, the process for these “bogus Cinerama films,” as director Joe Dante called them in Cinerama Adventure, “allowed the films to be much more fluid” and permitted the films to be made “in a somewhat more cinematic way. I think they lost something when they gave up the three-projector system but they gained a lot of flexibility. I think probably the later pictures are better because of it.” Although Mike Todd dubbed Cinerama “the greatest thing since penicillin,” Henry Levin admitted that he could have shot Grimm just as effectively on black-and-white film. “But, [Cinerama] will make Brothers Grimm a more memorable audience experience. And this makes it an important film, doesn’t it?” — Jim Lochner | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 05-01-25 |