"The Witness"

|

This article first appeared in |

| Written by: Rod Miller | Issue 60 - March 2000 |

|

|

Further in 70mm reading: |

70mm frame blow up from "The Witness". Picture supplied by Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center. 70mm frame blow up from "The Witness". Picture supplied by Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center."We went with the Arri for a number of reasons. I knew we'd be shooting a great deal of this show at night and the Arri viewfinder seemed brighter. I liked the matched set of Zeiss/Hasselblad lenses which we've used often since they are basically the same lenses used in the IMAX format. We also had a Cooke 38-210mm zoom which focuses at less than three feet. It helped on those little push-in's Keith sometimes likes to do. But the zoom also presented limitations in a couple of areas: low light, since it's a T/6.3 and there's obvious visible distortion in the wide angles. Camera speed range was another consideration, and the Arri gave us capabilities from four to 100 frames per second. "The Panavision HSHR weighs in at just 35 lbs--considerably lighter than the Arri at nearly 100 lbs--which made it great for hand-held shots and steadicam work. Of course Jeff Mart, our steadicam operator, would have preferred even less weight, but he handled it beautifully." One of the disadvantages with the Panavision camera is related to its pellicle system, Christensen says, which creates difficulties in a couple of areas. "It bleeds off about 1/3 of a stop to the viewfinder, so you're limited in low-light situations to start with. But the biggest problem is just being able to see through it, so it's harder to judge focus. At night, the edges of the frame were just gone, especially on video assist. Then in bright daylight, shooting at T/22 to gain more depth of field, it was really hard to even see what you're shooting and there is no Panaglow for it. And you can get ghosting or reflections off the pellicle. Plus, it's a fixed viewfinder, so it can be tough to see into as well. Speaking of depth of field, Christensen says it's just something you have to learn to live without in 65mm. As an example, a typical close up might require an 150mm lens (an 80mm lens may be considered a "normal" lens for this format) and positioning the camera at about eight feet away, five feet away for a tight close-up. That lens at eight feet at a T/4 results in a total depth of field of only two inches. You might try for a deeper stop and succeed in getting up to a T/8 and now the chart tells you that you've gained only an additional four inches! But our focus pullers--Zep Christensen, Gordon Huston, and Eddie Rodriguez--handled it well." |

Rod Miller Rod Miller is an ad agency writer/producer and creative director in Salt Lake City, Utah. He has also written for the advertising trade press and is an oft-published Cowboy Poet. |

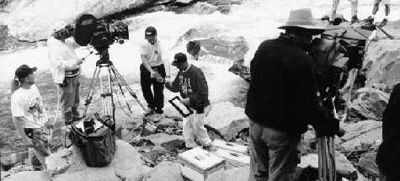

Director Kieth Merril (at right with hat) sets B camera. Both 65mm cameras are ARRI 765. Picture by T C Christensen. Director Kieth Merril (at right with hat) sets B camera. Both 65mm cameras are ARRI 765. Picture by T C Christensen.Meanwhile, back at pre-production, it was time to think about film stock. Christensen had tested Kodak's VISION stocks, 5277 and 5279. He'd seen that it showed a slight improvement in grain, and with the magnification involved in a big, wide-screen theater, even a slight improvement is welcomed so he ordered it, even though he couldn't find anyone who had used the stock yet in large format. Rick Gordon of RPG hadn't seen it and neither had anyone at the 70mm side of CFI. Although T.C. likes all the options Kodak offers in stocks, he also likes to keep things simple, using the fewest number of stocks to keep magazine changes to a minimum and short ends from piling up. "At $1 a foot," he said, "short ends and waste get incredibly expensive." So the decision was made to rely on 5293 for daylight exteriors, and the newer 5279 for daylight interiors, night shots, and any time depth of field problems raised it's ugly head. "At times, I pushed the 5279 one stop and rated it at 800 ISO. I worried about retaining inky blacks for our night exteriors with the push, but did some tests and found that at 800 ISO (as opposed to rating at 1000), I could get the deeper stop and the negative still stayed dense and held the blacks with hardly an increase in apparent grain. "Tennessee can cloud up and get pretty dark, even in the middle of the day." Christensen says. (Incidentally, although set in Connecticut, the film was shot on location in Tennessee and Maryland which are similar in terrain and appearance but less urban, offering more "17th century" vistas) "We shot one sequence under a canopy of trees at about 3pm that I ended up shooting with the 5279 pushed one stop just to get a T/4!" Christensen says, "Working with an ISO of 500 (using an 85 filter), that's only 40 foot candles in the middle of the day!" As for filtration, most of the film was shot clean, with an 85 or an 85 polarizer when at right angles to the sun to darken the sky. "NDs didn't play much of a part in this production. I usually welcome shooting at T/22 in this format. However, the Zeiss 110mm only stops down to a T/16, so daylight exteriors with that lens often required an 85n3." Christensen shoots a color chart / gray scale at the head of every roll and whenever there's a major shift in light condition. "I feel they give the color timer the best indication of what I'm trying to do with density and color rendition so it's worth the extra time they take to shoot them. As with most cinematographers, I've sometimes pulled the 85 filter on tungsten-balanced film to gain that additional 2/3 stop, but I've found that can create problems in timing because it so overloads the blue layer on the film. I know that the LLD filter was made just for this situation, but I have had great results using an 81C. It's light enough that you can get away without factoring it into your ISO if you're really hurting for light, or you can go with a correction of just 1/3 stop. I find the filter puts just enough warmth back into the negative that the timer or colorist can make the scene look as if it were shot with an 85, without the color shifts you sometimes get without it." |

|

A speed rail rig is used to capture a low angle running shot with the Panavision HSHR 65mm camera rig. Picture by T C Christensen. A speed rail rig is used to capture a low angle running shot with the Panavision HSHR 65mm camera rig. Picture by T C Christensen.Flashback sequences in the script demanded a different look and style to set them apart from the main story line. "All flashbacks were shot hand-held, and at higher frame rates--anywhere from 40 to 90 fps. We decided to print them for black and white, push a stop, under-expose a stop (rating the film at 2000 ISO), and add a Fog 2 to the filtration." Christensen says. "It turned out to be a great idea in pre-production but the hand-held part turned out not that easy of an idea to execute in production." The first hand-held sequence showed up on the shooting schedule ahead of the arrival date for the Panavision HSHR. So, I ended up walking around a 17th century clipper ship, swish panning and citching a hand-held, 100 lb Arri 765. I kept thinking about what would happen if I tripped and fell. I was hoping that if I did, the camera would just come down on top of me and crush the life out of me--that seemed a better option than having to call Arri and explain what I did to their camera! Then, near the end of production, a malfunction with the Panavision camera required Christensen to shoulder the Arri again for a final hand-held sequence. "The 765 came with 500 ft. mags that we thought would be nice for hand-held work and in tight quarters. But I found it easier to balance the camera with a 1000 foot mag, even though it added another 15 lbs or so to the overall weight. The bigger mag. put more of the weight on my shoulder, whereas the 500-footers required me to support nearly all the weight with my hands and arms," says Christensen. "I don't know how thrilled I'm going to be to ever shoot hand-held with a 100 pound camera again, but if I do, at least I've learned a few tricks. One of T.C's favorite shots in the film is one of those unplanned things that bless most productions. He had the idea to get a close up of an arrow moving through the sky. "There are several battles in the film and besides liking the shot, I thought it would give some additional cuts and pacing to the battle scenes." Property Master Lisa Egger furnished a couple of straight arrows with well-made tips. T.C. and key grip, Matt Stelling, discussed rigging it to the camera, then panning it quickly for a traveling shot of an arrow head. Stelling had the idea of creating spin in the arrow by attaching it to a power drill connected to a rheostat to control the speed of the arrow's spin. "To pull off the shot," T.C. says, "we used an 80mm Zeiss lens with a plus-one diopter. The arrowhead was about 12 inches in front of the lens. I shot 5279 in a semi-shaded area, and under-cranked the camera at 12 frames per second , with a straight 85. That gave me a T/11, with enough depth of field to get a sense of the leafy background and mottled light, without making it sharp enough to be distracting. Then I'd just spin the camera on the tripod for a 360-degree pan, which gave the editor, Kathleen Korth, takes that lasted about three seconds at 24 fps--plenty for a quick cut." |

|

70mm frame blow up from "The Witness". Picture supplied by Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center. 70mm frame blow up from "The Witness". Picture supplied by Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center.Firelight presented another challenge. "I'd guess that half of the film are scenes that use fire as their main motivation for light. It's nice to shoot a wide aperture with them which allows the firelight to affect the surroundings. But when you do, according to Christensen, "the flames themselves lose color and start to look bland. I think you get a better look by exposing for richer color in the fire and bringing in electric to light the surroundings." Pushing the 5279 one stop and shooting at T/8 worked well for the fires. Torching an entire village obviously results in more light, so Christensen shot those scenes at T/11, or occasionally at a T/8 without the push. In preproduction, My Gaffer, Rhett Fernsten suggested a concept to create realistic fire effects that would be mobile and quick to set up. He mounted three open face 2k lamps to 2 x 3 ft. pieces of plywood. These lamps were then connected to the 3 way "Magic Gadget" flicker box made by William McIntire in Portland Oregon. This enabled us to place a firelight quickly behind tents, logs, etc. and gave us multiple shadows because of the three lamps, which I like much more than flickering just one lamp to simulate fire. Then, we would vary the gel placed on each of the three lamps. Alternating between 1/4 CTO, 1/4 Straw. "As for the backgrounds, I wanted a bit of blue there to suggest night. I like the look of an HMI with 1/2 CTO for a moon look. But here, we went with just a 1/4 CTO, then shot the color chart with a 1/4 blue on the chart light." Christensen says, "That meant the color timer would see some blue in the chart and warm up the printer lights to get a normal 'white' light. That would in turn warm up our HMI's as well as add more color and life to the flames and our tungsten lights. The advantage of less correction is more stop. We always needed it. The Pequot War, for all practical purpose, killed off an entire people. Even today, more than 350 years later, only a few hundred Native Americans claim Pequot ancestry. The Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center near Mystic, Connecticut honors the Pequot tribe and Native Americans through the ages. T.C. believes that some stories are definitely worth the cost of 70mm production and "The Witness" is one of them. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 05-01-25 |