Come Back D-150 .... All Is Forgiven |

This article first appeared in |

| Written by: Grant Lobban, London | Issue 47 - December 1996 |

The Rob Hummel/TCMPT (The Technology Counsil

of the Motion Picture-Television Industry) Film Formats Seminar staged in

L.A., and later in London, was a unique opportunity to compare all the

current theatrical film formats. They ranged from a 35mm print made from a

Super-16 negative up to the 65mm/70mm system. All the various

negative/positive combinations, involving blow-ups and reduction were also

demonstrated. The same scenes were carefully photographed to give as near

possible the same vertical angle of view, with the horizontal coverage

depending on the individual formats aspect ratio. To maintain this level

playing field, all the rival formats were then compared on a screen with the

same height. This projection arrangement is now common practice in many of today's

theatres. In those which can still run 70mm, this means that the 70mm

picture is not the biggest (in terms of screen area), beaten by the wider

aspect ratio of the 35mm anamorphic format. The Rob Hummel/TCMPT (The Technology Counsil

of the Motion Picture-Television Industry) Film Formats Seminar staged in

L.A., and later in London, was a unique opportunity to compare all the

current theatrical film formats. They ranged from a 35mm print made from a

Super-16 negative up to the 65mm/70mm system. All the various

negative/positive combinations, involving blow-ups and reduction were also

demonstrated. The same scenes were carefully photographed to give as near

possible the same vertical angle of view, with the horizontal coverage

depending on the individual formats aspect ratio. To maintain this level

playing field, all the rival formats were then compared on a screen with the

same height. This projection arrangement is now common practice in many of today's

theatres. In those which can still run 70mm, this means that the 70mm

picture is not the biggest (in terms of screen area), beaten by the wider

aspect ratio of the 35mm anamorphic format.During the panel discussion, following the Seminars BKSTS re-run at London's National Film Theatre, it was suggested that the acknowledged superb picture quality of the 65mm/70mm system was not always enough to impress the public at large, who soon became accustomed to the enhanced image quality, and take it for granted once they become involved with the action on the screen. It was generally agreed that, like the original Todd-AO concept, the 70mm formats reserve of definition, brilliance and stability, should always be used to provide audiences with an appreciably bigger picture, to help make a 70mm presentation something special and more memorable. There was a call for the return of giant deeply curved screens. Once common in many theatres during the 1960s and 70s, they are now usually only to be found at special venue theatres and at Theme Parks, often as part of their film-based simulation rides. |

Further in 70mm reading: |

Although a very deeply curved screen was a feature of the very first Todd-AO

shows in 1955, the structural problems when adapting theatres, together with

controlling image distortion, saw a marked decline in their use in later

70mm installations. However, in 1963, when Cinerama abandoned its triple

35mm projector set-up in favor of projection a single 70mm print onto its

original curved screen, there was renewed interest in this form of

presentation. For a time, one of Cineramas chief rivals was the

Dimension-150 process. Although a very deeply curved screen was a feature of the very first Todd-AO

shows in 1955, the structural problems when adapting theatres, together with

controlling image distortion, saw a marked decline in their use in later

70mm installations. However, in 1963, when Cinerama abandoned its triple

35mm projector set-up in favor of projection a single 70mm print onto its

original curved screen, there was renewed interest in this form of

presentation. For a time, one of Cineramas chief rivals was the

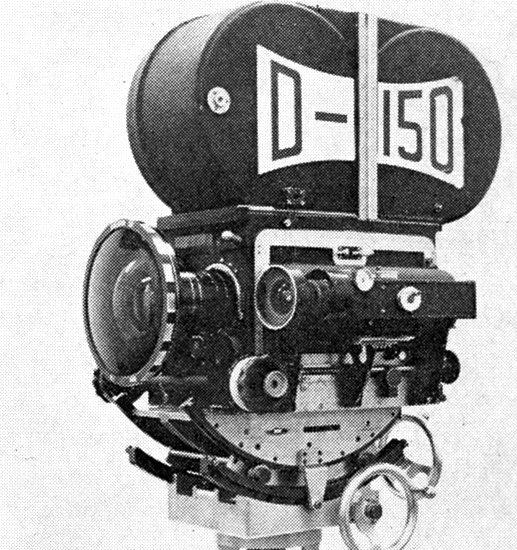

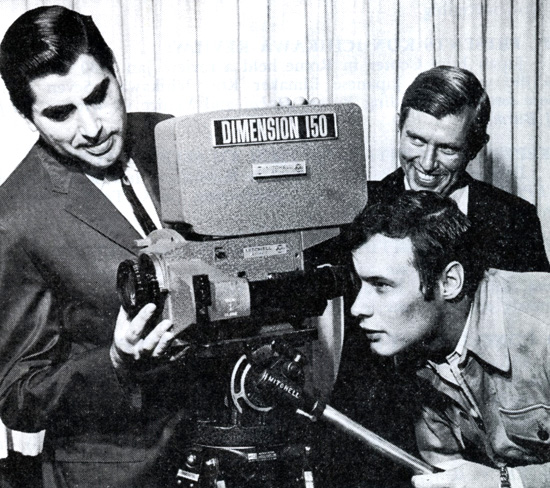

Dimension-150 process.Also known simply as D-150, it was the invention of two Faculty members of the University of California, Dr Richard Vetter, who was assistant professor of Audio-Visual Communication, and Carl W. Williams, an instructor in the same department. The system was a scaled-up version of an earlier development of theirs for a driving simulator. The theatrical process consisted of three elements, which could be used as a complete system or used independently. The first was a camera system employing the conventional 65mm/70mm format together with a range of spherical camera lenses giving horizontal fields of view of 50 degrees, 70 degrees, 120 degrees and an ultra-wide 150 degrees (18mm), which gave the process its overall title. Next was a special printer lens which modified the geometry of the image on the print, making it more suitable for projecting onto a deeply curved screen. Finally, there was the D-150 presentation system with a large deeply-curved screen designed to give audiences the same sense of participation as Cinerama. |

|

Introduced in 1966, the photographic system was first used for the Dino De

Laurentiis production "The Bible...in the beginning",

directed by John Huston. However, it was as a presentation process that it

gained the most acceptance. In order to make it attractive to theatre

owners, it was designed to be a multi purpose system, which could also show

normal 70mm and 35mm formats on smaller segments of the same screen. The

screens varied in size from 24 x 57 feet (7,3 x 17,4 meters) up to 35 x 90

feet (10,7 x 27,4 meters) and were curved around a 120 degree of arc. The

apparent widths, when viewed head-on, (across the cord) ranged from 48 feet

to 73 feet (14,6 to 22,3 metres respectively). The screen, made by Andrew

Harkness in England had a relatively low-gain matt surface with a special

"low scatter coating" to help keep cross reflections and loss of

contrast to a minimum. To fill the screen, a special projection lens was

developed. Using a Vetter/Williams formula, it was manufactured by the

Kollmorgen Corporation in America. Appropriately called the "Curvulon"

it curved the projected image around the screen. The wide-angle lens had a

large 4 inch diameter elements designed to give uniform light distribution

and minimum fall off. The basic lens was fronted by a rectangular element

which was specially ground for each individual theatres throw and screen

size and kept the projected image in focus around the screen. These were

only needed for the special D-150 presentations when the picture filled the

entire screen area. The other formats, 35mm wide screen, 35mm CinemaScope

and conventional 70mm were shown on smaller portions of the screen. For

these, the theatres existing projection lenses were used, after being

"corrected" by the D-150 company to introduce a small amount of

curvature of field, which helped maintained the focus on their appropriate

segments of the screen. Introduced in 1966, the photographic system was first used for the Dino De

Laurentiis production "The Bible...in the beginning",

directed by John Huston. However, it was as a presentation process that it

gained the most acceptance. In order to make it attractive to theatre

owners, it was designed to be a multi purpose system, which could also show

normal 70mm and 35mm formats on smaller segments of the same screen. The

screens varied in size from 24 x 57 feet (7,3 x 17,4 meters) up to 35 x 90

feet (10,7 x 27,4 meters) and were curved around a 120 degree of arc. The

apparent widths, when viewed head-on, (across the cord) ranged from 48 feet

to 73 feet (14,6 to 22,3 metres respectively). The screen, made by Andrew

Harkness in England had a relatively low-gain matt surface with a special

"low scatter coating" to help keep cross reflections and loss of

contrast to a minimum. To fill the screen, a special projection lens was

developed. Using a Vetter/Williams formula, it was manufactured by the

Kollmorgen Corporation in America. Appropriately called the "Curvulon"

it curved the projected image around the screen. The wide-angle lens had a

large 4 inch diameter elements designed to give uniform light distribution

and minimum fall off. The basic lens was fronted by a rectangular element

which was specially ground for each individual theatres throw and screen

size and kept the projected image in focus around the screen. These were

only needed for the special D-150 presentations when the picture filled the

entire screen area. The other formats, 35mm wide screen, 35mm CinemaScope

and conventional 70mm were shown on smaller portions of the screen. For

these, the theatres existing projection lenses were used, after being

"corrected" by the D-150 company to introduce a small amount of

curvature of field, which helped maintained the focus on their appropriate

segments of the screen.Installing D-150 usually involved extensive remodeling of the auditorium, with some loss of seating to make room for the screen. The largest screens, together with their masking and curtains, took up 40 feet of the depth (12,1 meters) of the auditorium. D-150 was best suited to stadium style seating, with the viewing distance from the screen spaced between one fifth and twice the cord width. A near level projection angle was also specified, (or at least, no greater than 6%), which sometimes meant that a new projection room had to be built lower down an below any balcony. The D-150 process did certainly add extra impact to both specially shot D-150 and conventional 70mm films. Like other deep-curve and dome screen systems, it was not perfect, especially for those seated away from the prime seating positions. The best view, giving an undistorted image, was from directly in front of the screen and not too far back, to maintain the participation effect. The results from the off-center seats was far less satisfactory. Like any object, a cinema screen viewed from the side shows a foreshortening effect, with characters appearing slimmer. On a flat screen, this effect is expected and accepted as normal, but on a deeply curved screen the figures are seen to change shape from stout to thin as they move across the screen, which is far less acceptable. To help counter this effect, the special D-150 printer lens was developed and could be employed when making 70mm prints from both 65mm negatives and blow-ups from 35mm negatives. |

|

When viewed head-on, the D-150 curved picture had a familiar butterfly

shape, with an aspect ratio of approximately 2:1, closely matching that of a

normal 70mm print. However, if the screen was flattened out, the aspect

ratio would increase to about 2,7:1, with the picture being distorted to

fit. This shows up as a non-linear horizontally stretched image, becoming

greater towards the sides of the frame. Also, as the center of the screen

was up to 20 feet further away from the projector than the sides, the

greater magnification meant the picture had to be progressively cropped at

the center. Films made in D-150 took this into account when composing the

image in the camera, but for others, without the added headroom, the effect

often spoiled the composition. To help counter-balance these effects, the

combination of the special printer lens and the D-150 projector lens

bowed-in the image slightly at the center and progressively squeezed the

image at the sides of the frame. The result was not entirely successful, as

it just shared out the distortion amongst the audience. Those at the sides

of the auditorium saw a slight improvement, but only at the expense of those

in the more ideal positions directly in front of the screen, who, if in the

know, could spot the printed-in counter distortion, particularly if the

camera panned. Many film companies, who signed up to have their films

presented in D-150, often declined to have the special prints made. Apart

from their questionable value technically, they could not be used, after the

D-150 showings, in normal theatres. When viewed head-on, the D-150 curved picture had a familiar butterfly

shape, with an aspect ratio of approximately 2:1, closely matching that of a

normal 70mm print. However, if the screen was flattened out, the aspect

ratio would increase to about 2,7:1, with the picture being distorted to

fit. This shows up as a non-linear horizontally stretched image, becoming

greater towards the sides of the frame. Also, as the center of the screen

was up to 20 feet further away from the projector than the sides, the

greater magnification meant the picture had to be progressively cropped at

the center. Films made in D-150 took this into account when composing the

image in the camera, but for others, without the added headroom, the effect

often spoiled the composition. To help counter-balance these effects, the

combination of the special printer lens and the D-150 projector lens

bowed-in the image slightly at the center and progressively squeezed the

image at the sides of the frame. The result was not entirely successful, as

it just shared out the distortion amongst the audience. Those at the sides

of the auditorium saw a slight improvement, but only at the expense of those

in the more ideal positions directly in front of the screen, who, if in the

know, could spot the printed-in counter distortion, particularly if the

camera panned. Many film companies, who signed up to have their films

presented in D-150, often declined to have the special prints made. Apart

from their questionable value technically, they could not be used, after the

D-150 showings, in normal theatres.Although not perfect, the D-150 presentation system was soon being installed in theatres around the world. The D-150 company gained a partner, when Todd-AO joined on to improve the process and help market, license and service both productions and theatres. Todd-AO continued to offer its own 65mm/70mm process, considering the D-150 system to be a complementary alternative, helping it to compete with Cinerama. D-150 already used Todd-AO/Mitchell 65mm cameras but could now provide producers with a wider range of lenses, including a couple of zooms. In Britain, the projection process was handled by Rank Audio Visual Limited, who, at the time, also controlled Andrew Smith Harkness Limited, the supplier of D-150 screens. To show their confidence in the system, Rank installed it in many of its own Odeon cinemas, including London's D-150 flagship theatre, the Odeon, Marble Arch, which was actually built in 1966 from ground-up around the D-150 process. However, D-150 soon ran into financial trouble and disagreements with its partners. Only one other feature was actually photographed using their camera lenses, this being "Patton" released in 1969. Theatres adopting the system had purchased all the necessary equipment outright, except for the special D-150 projection lenses, which were loaned free of charge for use when showing films on the full D-150 screen. So, apart from the share of the profit following the initial supply of equipment, the only income was the licensing fees and royalties from the individual showings. Unfortunately, having paid good money to have D-150 installed, and wishing to give their audiences the biggest possible 70mm picture all the time, many theatre owners showed many films in D-150 "unofficially" without paying. |

|

To add to Vetter and Williams troubles, Harkness began marketing the screen

independently, crating a rivial deep-curve system called Vistarama, which

was free of any royalties. After unsuccessful legal action, the D-150

company folded in 1970. Before it was finally wound up, the liquidators

offered each individual D-150 theatre the chance to purchase their special

D-150 lenses outright and continue to use the D-150 trademark when promoting

their shows. However, many theatres chose to send their lenses back and some

even managed to continue filling the full size screen using conventional

lenses. Rank returned most of theirs, including those at Marble Arch, not

wishing to pay the asking price of around 3.500 punds a pair. They did

rustle up a replacement pair for the theatre, when it revived the system in

1977 for special presentations of "Star Wars". Most D-150

and other deep-curve screens were finally thrown out during the 1980s,

resulting from the changing pattern of cinema distribution, with the move to

multi-screen complexes and smaller auditoriums. To add to Vetter and Williams troubles, Harkness began marketing the screen

independently, crating a rivial deep-curve system called Vistarama, which

was free of any royalties. After unsuccessful legal action, the D-150

company folded in 1970. Before it was finally wound up, the liquidators

offered each individual D-150 theatre the chance to purchase their special

D-150 lenses outright and continue to use the D-150 trademark when promoting

their shows. However, many theatres chose to send their lenses back and some

even managed to continue filling the full size screen using conventional

lenses. Rank returned most of theirs, including those at Marble Arch, not

wishing to pay the asking price of around 3.500 punds a pair. They did

rustle up a replacement pair for the theatre, when it revived the system in

1977 for special presentations of "Star Wars". Most D-150

and other deep-curve screens were finally thrown out during the 1980s,

resulting from the changing pattern of cinema distribution, with the move to

multi-screen complexes and smaller auditoriums.Despite its shortcomings D-150 was certainly something special and providing you knew the best place in the auditorium to sit, it added to the enjoyment of seeing many of the epics of the 1960s an 70s. Even sitting in the front of the vast curved curtains, while waiting for the film to start, increased the sense of anticipation. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 05-01-25 |