Cinema Digital Sound - System Overview |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Ronald E. Uhlig, Eastman Kodak Co. & Howard J. Flemming, Optical Radiation Corporation. Presented by Jack Johnson, Optical Radiation Corporation. Text prepared from a vintage papers by Anders M. Olsson, Lund, Sweden | Date: 04.04.2017 |

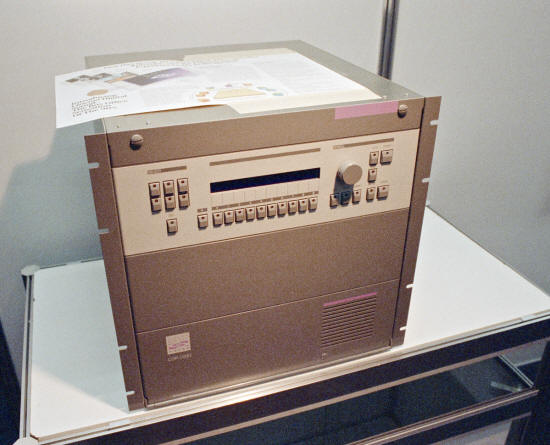

CDS

Controller. Click to see enlargement. Picture by Thomas Hauerslev CDS

Controller. Click to see enlargement. Picture by Thomas HauerslevWith the showing of last summer's hit film, Dick Tracy, the public had its first opportunity to hear an exciting new sound format for motion picture film: CINEMA DIGITAL SOUND. Since last summer a number of other major studio motion pictures have been released in CDS with more following. Cinema Digital Sound, or CDS for short, is a format for obtaining six channels of digital sound on motion picture release prints. Ever since the compact disc was launched as an alternative to the vinyl phonograph record, the motion picture industry has dreamed of having that level of quality available on every motion picture print. CDS offers that possibility in a system that is practical and cost effective, advantages that will allow it to become the universal release sound track format. CDS was born out of work begun at Eastman Kodak to develop a sound format that would permit compact-disc-quality sound, suitable for high end special venue formats such as Showscan, but at the same time capable of being recorded in the normal sound track area of 35mm prints. It was obvious that the new format would have to be digital as only a digital system could offer all the desired benefits: six discrete channels, consisting of five full bandwidth channels and one subwoofer channel; full audio bandwidth; and the reduction of noise, flutter, and distortion to the vanishing point. No envisioned optical analog system could offer all of these. However, to be a suitable candidate for a universal motion picture audio format, the system had to be practical. We ruled out expensive and exotic systems such as interlocked optical discs. It is clear that current technologies, such as the use of SMPTE time code, provide ways of synchronizing just about anything to motion picture film. However, no system exists that is both reasonable in cost and convenient for recording a motion picture sound track. Consider the compact disc. It has a playing time of about 70 minutes and a capacity of two channels. To record a motion picture that is 90 to 120 minutes long and requires six channels for an effective presentation would require a total of six compact discs and perhaps six compact disc players in the theater. Obviously, this is not the ideal medium. Even if a practical recording ideal medium did exist, industry experts say that the problems of getting the right sound with the right reel of picture through the production and distribution system to the exhibitor preclude any sort of double system from ever being used on a widespread basis. There will always be limited run and special venue situations where a double system is best, but never as the general motion picture sound release format. Striped magnetic prints overcome the double system problems, but they introduce a new set of problems. First of all, putting the magnetic stripes on the prints is costly and time consuming. Secondly, the stripes wear and the magnetic heads that contact them wear. The initial high quality that magnetic sound offers is all too often not presented in the real world theater. Thus we centered out attention on the straightforward approach of putting an optical digital sound track right on the print, using the dyes of the current "Eastman" color print film to image clear and dark bits in the normal soundtrack area. At Eastman Kodak a program was started to determine whether the films and equipment have the necessary resolving power to image the small bit size that would be needed to record the millions of bits per second that were required to record the desired number of tracks of CD quality digital sound. Subsequent tests at Eastman Kodak showed that it was indeed possible and that the error rates were low enough to be easily correctable by today's error detection and correction techniques. |

More in 70mm reading: Films presented in 70mm and 35mm Cinema Digital Sound List of cinemas with CDS equipment Cinema Digital Sound - Sounds Like The Real World Internet link: ORC c/o Britannia House 1/11 Glenthorne Road London W6 OLF |

CDS

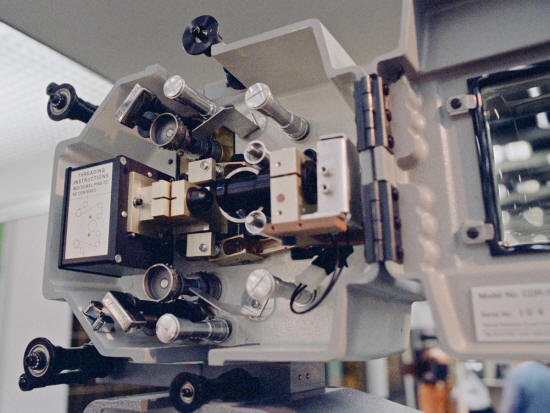

Penthouse Reader. Click to see enlargement. Picture by Thomas Hauerslev CDS

Penthouse Reader. Click to see enlargement. Picture by Thomas HauerslevAt this point we at Optical Radiation Corporation entered the picture and completed the development of CDS. Perhaps ORC needs a little introduction to the motion picture audio community, although I doubt that it needs introduction to those in exhibition. ORC has a distinguished history as the supplier of Century projectors and Orcon high-intensity projector lamphouses. ORC had reached similar conclusions about the value of a digital sound track to the motion picture industry, and after hearing about the positive results of their feasibility study, we contacted Kodak. Led by Howard Flemming, the team at ORC developed the recording and playback equipment necessary to make CDS a reality. Kodak has developed a special film for recording the CDS sound negative. Both companies continue to work together to introduce CDS to the motion picture industry. With that introduction, let me tell you a little bit about the CDS system. I will be giving you just an overview of Cinema Digital sound. Tomorrow morning, however, at the Laboratory and Sound sessions Ron Uhlig of Eastman Kodak Company giving two papers that go into much more detail about the technical wizardry that has been put into CDS. An interesting feature of modern digital electronic technology is that it is possible to have a product that is both complex and simple. Ron will tell you tomorrow about some of the complexity, but I'm here to tell you now that the CDS decoder in the projection room of a theater is simpler to operate than the VCR in your family room at home. Originally CDS was offered in only 70mm format but it is now available in both 35 and 70mm. So just keep in mind that everything I say about CDS applies to both the 35 or 70mm format. There is no difference in how we put CDS on 35 and 70mm film. The 70mm film just runs a little faster. This slide shows clips of both 35 and 70mm film with CDS sound tracks. The CDS track is the magenta colored strip just to the left of the picture. In both cases, the CDS tracks occupy the area that was formally occupied by the analog sound track. In 35mm that analog track would have been a variable area optical sound track and in 70mm, one of the four magnetic stripes. If we zoom in on the CDS track, we can see that the track is composed of black and white squares. Actually, they are magenta and white. Each square is one bit of data, either a one or a zero. For the benefit of those of you sitting further back, we'll zoom in even further. Each individual bit is 14 by 14 microns. On one hand, this might seem pretty small, but on the other hand, it doesn't really push the limits of the system so much that it requires exotic equipment to print the data onto the film. This print was made from a CDS negative on a standard Bell & Howell model C printer. Going back to the overall view of the track, there are 180 columns of bits across the sound track, which is just slightly over one-tenth of an inch wide. Since the bits are square, we can easily calculate that there are approximately 32,500 row of bits in each second of film and, if you are interested, that adds up to a total of almost 6 million (5,850.00) bits per second. |

|

"Terminator

2: Judgement Day" at the Imperial Bio, Copenhagen (Denmark) in full Cinema

Digital Sound, 1992.

Picture by Thomas Hauerslev "Terminator

2: Judgement Day" at the Imperial Bio, Copenhagen (Denmark) in full Cinema

Digital Sound, 1992.

Picture by Thomas HauerslevHowever, as you can see, there is virtually no space left between the track and the picture and the track and the perforation. What about weave in the projector? It turns out that there is enough redundancy in the data so that only 152 of the 180 bits need to be read. Thus it doesn't matter if the scanner in the projector reads 152 in the middle or near the perforation or near the picture. The scanner will find the 152 that it needs, in the process giving plenty of allowance for weave. With that brief look at the film, let's take a look at the recording and reproduction processes, beginning with recording. Recording and printing a CDS track is little different from recording and printing a standard variable area sound track, and intentionally so. One goal was not to require any exotic recording apparatus, such as a laser on the optical printer. The recorder for exposing the sound track negative looks similar to a conventional sound track recorder, although its electronic guts are much different. A light emitting diode array is used to expose the film. A special sound negative film, 'EASTMAN' Digital Sound Recording film type 2374, has been developed by Kodak to work with the spectral output of LED array but yet be process compatible with the D-97 process used for conventional sound negative film. A useful feature of the recorder is its ability to record a human readable message in the sound track area. In both the leader and trailer of the film, sound track identification is printed, along with patches for measuring the density of the negative and the print. The arrow always points towards the head of the reel. Printing the sound track is done on a conventional contact printer. Successful prints have been made on all the types of contact printers commonly used for release printing. Of course, since there is no current optical sound track on 70mm prints, 70mm printers don't have separate sound heads. However, labs can either print in two passes, the practice that has been followed to date for obtaining 70mm CDS prints, or a sound head can be added to existing 70mm printers. We have arranged for such a sound head to be designed and tested. Another interesting feature of 70mm CDS tracks is that they are printed from a 35mm width negative. The advantage of this is that the same recorder and film stock can be used as for 35mm tracks and it is not necessary to develop 70mm D-97 processing capability. Of course, the negative film runs 25% faster when making 70mm negatives and the bits are stretched out by the same proportion. Experience has shown that, while the printer does need to be fairly well adjusted and maintained for CDS tracks, no special modifications are necessary. While we are talking about CDS in the laboratory, its a good time to note that CDS tracks are printed with the sound and pictures in editorial synchronisation. There is no sound track offset. The playback equipment can be easily adjusted for varying distances between the sound head and the picture gate. Lack of an offset makes it easy to splice prints without sound track sync. problems. The final printing feature I will mention is that sound track application is optional. The scanner is designed to read dye sound tracks but will also work perfectly well with applicated tracks. The processing industry has long been looking for a way to get rid of sound track application, and this is it. However, until a lab is substantially converted, it may actually be simpler to just applicate everything, and not have to worry about giving CDS prints special processing treatment. |

|

"T2"

at the Imperial Bio, Copenhagen (Denmark) with CDS reader on top of the

DP70, 1992.

Picture by Thomas Hauerslev "T2"

at the Imperial Bio, Copenhagen (Denmark) with CDS reader on top of the

DP70, 1992.

Picture by Thomas HauerslevAll in all, it is a significant advantage of CDS tracks that they can be printed with the same techniques and equipment used for conventional sound track prints. High volume, low cost prints will continue to be a way of life. Playback of CDS sound takes place with the addition of these two pieces of equipment to the projection booth. The CDS scanner mounts on top of the projector. If the projector has an existing penthouse, the CDS scanner mounts on top of it. There is no interference with existing sound scanners, either magnetic or optical. As I mentioned before, no particular sound head to picture gate displacement in the projector is required. The equipment has an electronically adjustable sound delay to obtain synchronization. The scanner uses a tungsten light source and a 512 element CCD array to scan the sound track. Each row is scanned once, and only once, and the information is fed to the decoding package. The scanner we see here can be used to play either 35 or 70mm CDS tracks. Changing from one format to the other takes only a few minutes. The decoder is where all the wizardry takes place. It must control both the horizontal and vertical scanning so as to synchronize it with the data on the film, and then undo all the encoding that took place when the negative was recorded. In the process, it corrects for any damage in the form of dirt and scratches that may exist on either the negative or the print. All in all, the process is very complex, and once again I invite you to hear more about it in tomorrow morning's papers. However, the vast majority of the electronics is digital, and once it is implemented in integrated circuits as the CDS system is, the entire system is very reliable and stable and will seldom, if ever, need adjustments or maintenance. A front panel liquid crystal display allows control of the few functions the projectionist needs control over, such as a master gain control. A password can be keyed in which allows authorized service personnel to access the setup functions, such as synchronization delay and individual channel volumes. The unit is fully compatible with existing sound equipment the theater and allows feed through of the analog audio signals from, for example, a Dolby CP-200. The CDS decoder automatically switches to digital if valid CDS data is on the film and back to analog when it is not. Thus digital and analog material can be intermixed on the same platter, if necessary, and the switch over will be fully automatic. Also automatic is projector changeover. Two scanners can be connected to one decoder package and the decoder can be interfaced with the booth's existing changeover circuitry to make the process completely automatic. Now let me talk a little about performance of the system. First, let's consider digital data performance. The most fundamental measure of performance of any digital recording system is what is known as the bit error rate. This is simply the fraction of bits that are misinterpreted on playback. For example, a small piece of dirt may cause a clear bit, a zero, to be read back as a one. Obviously, we would like the number of errors to be zero but this will never be the case. Even a piece of film fresh from the processing machine will have some dirt on its surface and the amount can increase each time the film is projected. Thus the system must be built to expect errors and correct for them. The CDS system has been designed to be able to play sound with no loss in quality even with a bit error rate as high as 10, of in other words, with one bit in every 100 incorrect. Although it depends somewhat how the errors are spread out on the film, this means that in a typical second, you could have as many as 50,000 errors, and still not be able to hear any problem with the sound. So, if that is how many we can stand, how many do we typically have? Well, a fresh print will have in the range of 1000 to 1500 errors per second, and after a few hundred passes, this may increase to perhaps 5000. As you can see, this still gives us a generous margin of protection relative to the 50,000 errors per second handling capacity of the system. Even if there are occasional bursts of errors over that rate, such as might occur at a splice, an efficient concealment mechanism renders them almost always inaudible. But what is really important is audio performance, so let's run down the audio specifications. |

|

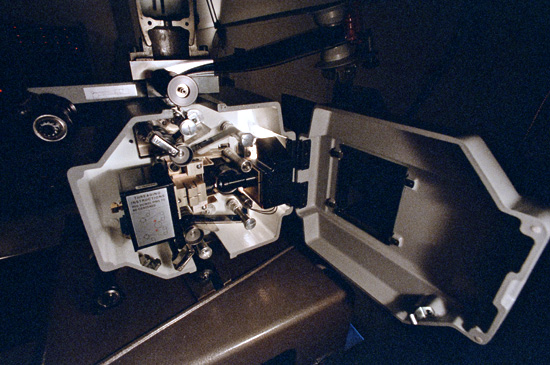

Close-up

of CDS reader at the Imperial Bio, Copenhagen (Denmark), 1992.

Picture by Thomas Hauerslev Close-up

of CDS reader at the Imperial Bio, Copenhagen (Denmark), 1992.

Picture by Thomas HauerslevFirst, CDS is a six channel system. Five are full bandwidth channels, and the sixth is a dedicated low frequency subwoofer channel. Over the years, this number of channels has developed as the optimum number even for the most dramatic audio special effects. The channels are placed around the theater as follows: three behind the screen, left, centre, and right; separate left and right surrounds; and the subwoofer, also typically placed anywhere behind the screen. The next important specification is frequency range. CDS covers the entire audible frequency range from 20 to 20,000 Hertz with a consistency and flatness only a digital system can attain. The improvement in high end clarity over what can be attained with current analog optical tracks will be truly significant. Distortion and flutter are two defects in audio quality that are reduced to the vanishing point in the digital CDS system. CDS will deliver six channels of crystal clear sound, free of distortion, hiss, pops, and other noises on either 35 or 70mm print film. It is, in effect, the motion picture equivalent of the compact disc sound we now enjoy at home. But good sound is not all that CDS will offer. There are three additional streams of digital data. Altogether, they have a total capacity of about 5000 characters per second. The first is a control channel that outputs data in the Music Industry Digital Interface -- or MIDI -- format. Data recorded in this area can be used for a variety of theater automation purposes or perhaps for subtitles in several languages. An example of a theater automation function that this channel might be used for would be for control information to hydraulically controlled seats that tilt, shake or move. The second type of data is SMPTE time code, identifying each frame of film with a complete address. This also can be used for automation purposes in theater but in addition can be a useful tool when searching for and inserting replacement sections of damaged prints. Finally, there is a film ID field which can be used to record the title of the feature along with, perhaps, a version number, language, and production number. These bits of data are important keys that will allow the CDS sound track to interface with ever more sophisticated systems well out into the future. Now that you know what CDS is, let me give you a little information about its use so far and about our future plans. During last summer's release season, two films were released with CDS sound tracks. These were Dick Tracy and Days of Thunder. A total of eleven theaters were converted to play these films and hundreds of showings were made. Since that time a further twenty cinemas have been converted in the USA and twelve in Europe for such releases as Edward Scissorhands, The Doors, Final Approach and Flat Liners to mention a few. I hope this introduction to Cinema Digital Sound has helped you understand some of the excitement we have regarding the future of motion picture sound. Analog sound tracks for motion pictures have been around for about 50 years now. We fully expect that 1991 will mark the turning point and that Cinema Digital Sound will become the standard sound system for the next 50 years. The reaction of those who have heard it, from industry experts to the average theater goer, certainly points in that direction. Finally if you wish to hear CDS will you please contact the BKSTS for tickets for this evening's screening at BAFTA of our demonstration film and a pre: UK premiere of a major studio release encoded in CDS. Thank you. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 05-01-25 |