Mixing Dolby Stereo Film Sound |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Larry Blake. From the February 1981 issue of Recording Engineer/Producer (Volume 12, No. 1). Copyright © 1981 by Larry Blake. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Text retyped from Dolby Laboratories S81/3242 | Date: 12.12.2015 |

|

Larry Blake will be publishing this article in

Spring 2016 in an anthology along with 35 other feature articles that he

wrote between 1981 and 2015, covering the span of film sound through that

era. At the same time, he will also be publishing an anthology of his

columns through that era, in addition to publishing the autobiography of

Murray Spivack, the Hollywood film sound great whose work graced a high

percentage of the films released in the first heyday of 70mmOklahoma!,

Around the World in 80 Days, South Pacific, Porgy and Bess, The Alamo,

Spartacus, West Side Story, Cleopatra, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, The

Bible, The Sand Pebbles, Doctor Doolittle, Star!, Hello, Dolly!, Patton, and

Tora! Tora! Tora! For information how to purchase these books, please write Larry Blake - Book purchase. |

|

Mixing Dolby Stereo Film Sound |

|

The release in 1977 of George Lucas'

"Star Wars" was to the Dolby Stereo

System and stereo film mixing what The Jazz Singer had been to Vitaphone and

film sound 50 years earlier: it simultaneously brought the system to the

attention of both the film industry and the general public. The success of

both processes marked to the public at least the unofficial beginning of

work that had been quietly underway for several years. Experiments at Bell

Telephone Laboratories created the first viable sound system for films;

Dolby Laboratories went one step further and tried to improve the sound

quality. The growth of Dolby Stereo in the past three years can best be

summarized with a list of the highest-grossing films of that period. The release in 1977 of George Lucas'

"Star Wars" was to the Dolby Stereo

System and stereo film mixing what The Jazz Singer had been to Vitaphone and

film sound 50 years earlier: it simultaneously brought the system to the

attention of both the film industry and the general public. The success of

both processes marked to the public at least the unofficial beginning of

work that had been quietly underway for several years. Experiments at Bell

Telephone Laboratories created the first viable sound system for films;

Dolby Laboratories went one step further and tried to improve the sound

quality. The growth of Dolby Stereo in the past three years can best be

summarized with a list of the highest-grossing films of that period."Close Encounters Of The Third Kind", Saturday Night Fever, Grease, Superman, and "The Empire Strikes Back" have all carried the Dolby logo, leading to the installation of Dolby cinema-sound processors in over 2,500 theaters world-wide by December 1980 a number which grows at a rate of 50 per month in the USA alone. Over 150 films have now been released with Dolby-encoded sound tracks. A less public side effect has been the installation of new stereo re-recording (dubbing) consoles at most major Hollywood sound studios, many of which had not been replaced since the advent of stereo dubbing in the Fifties. Also during this time the complexity and practically limitless possibilities of stereo mixes has introduced film sound engineers to equipment and techniques that were pioneered in the recording and broadcast industries. Digital delay lines, SMPTE time-code interlock, noise-reduction processing and computer-assisted dubbing have now become an integral part of all film mixing. The blending of the recording and film industries was tangible in the immediacy of the live rock concerts captured for The Buddy Holly Story, The Last Waltz and The Rose, while The Wiz, Hair, and "Apocalypse Now" put pre-recorded tracks to similar use. All of these films have relied heavily on the fusion of state-of-the-art film and recording studio techniques. This article will trace the history of stereo sound in motion pictures, the development of the Dolby Stereo System, and the steps involved in the recording, mixing and exhibition of a Dolby Stereo film. |

More in 70mm reading: Mixing Techniques for Dolby Stereo Film and Video Releases "In 70mm and 6-track Dolby Stereo" Presented in 70mm Dolby Stereo Dolby CP100 Cinema Processor Internet link: ested.com Larry Blake Swelltone Labs 400 Lafayette St. Suite 120 New Orleans LA 70130-3349 USA Work: (504) 299-0082 dolby.com |

The Early Years | |

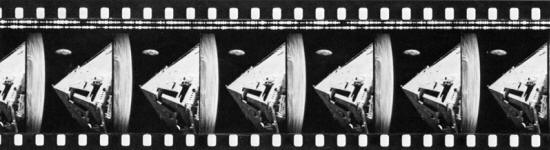

Figure 1.

A sample frame from a 1936 Blumlein stereo optical film,

showing the use of two variable-area soundtracks. Figure 1.

A sample frame from a 1936 Blumlein stereo optical film,

showing the use of two variable-area soundtracks.In an excellent article in the February 1939 issue of the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, W. H. Offenhauser, Jr., and J. J. Israel review early attempts at multiple-channel film sound, beginning with the 1911 patent of A. Rosenberg, whose "system" simply entailed recording sound from two microphones on two optical recorders. The authors go on to note that "other inventions may be classified as frequency characteristic variation (sic); still others have shown multiplicities of microphones, multiplicities of amplifiers, multiplicities of recording means, and multiplicities of loudspeakers; others disclose dummy heads and their equivalents with microphonic ears." (The interested reader is referred to the bibliography and patent references accompanying their 1939 article.) It is extremely doubtful whether any of the inventions had a life out of the patent office and the blackboards of their inventors. In all probability, the stereo optical soundtrack first saw the light of a projector in 1935, as recorded by stereo pioneer A. D. Blumlein. The sample frame in Figure 1 shows two variable area tracks. On November 13, 1940, Walt Disney's Fantasia was released with a three-channel soundtrack on a separate film, running in interlock with the picture, to allow for double-width tracks. A fourth track carried control tones to increase (by up to 20 dB) the levels of the three main speakers, placed left, center and right behind the screen. Notching on the side of the soundtrack could place front information on either side wall or in the ceiling. Most of the music for Fantasia was recorded on eight optical recorders at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. Six channels were devoted to individual sections, one to a balanced mix, and another to a distant microphone. This allowed for overdubbing a few bars of one section, if necessary. In its original engagements, Fantasia was released in "Fantasound" to only 14 theaters, because the onset of World War II prevented the building of further sound systems, each of which cost $ 45,000 and weighed 15,000 pounds. The premier of This Is Cinerama, on September 30, 1952, touched off the wide-screen and stereophonic sound sweepstakes of the Fifties. Cinerama's sound system utilized five loudspeaker channels behind the screen, and one on each of the side walls. The seven-track magnetic film ran in interlock with three projectors used to cover the 75-foot-long, 146 degree curved screen. Many film scenes were recorded with seven tracks of true stereophonic information, and it can safely be stated that this film was the first contact millions of Americans had with high-fidelity sound recording. The three-camera/projector system was cumbersome and expensive, however, and last used in 1963. In the spring of 1953 Warner Brothers' two-projector 3-D film, House of Wax, utilized a three-channel magnetic soundtrack in interlock, a standard mono optical track on the right projector being used to feed surround speakers in the auditorium. The left projector contained a mono mix as emergency back-up. |

|

Stereophonic Soundtracks | |

Composite stereo prints were first used in Twentieth Century-Fox's

CinemaScope process, which is best known to the public for its wide-screen

anamorphic lens system. The Robe was the first CinemaScope film, released on

September 16, 1953. Production dialogue was recorded originally in stereo

with three cardioid microphones, each capturing sound for a third of the

screen. This awkward system continued until 1958; thereafter mono dialogue

was panned to follow the action. "Swinging" dialogue was standard practice

in stereo films during the late Fifties and Sixties, but is not done much

anymore. Composite stereo prints were first used in Twentieth Century-Fox's

CinemaScope process, which is best known to the public for its wide-screen

anamorphic lens system. The Robe was the first CinemaScope film, released on

September 16, 1953. Production dialogue was recorded originally in stereo

with three cardioid microphones, each capturing sound for a third of the

screen. This awkward system continued until 1958; thereafter mono dialogue

was panned to follow the action. "Swinging" dialogue was standard practice

in stereo films during the late Fifties and Sixties, but is not done much

anymore.Re-recording was done to four tracks, with three loudspeaker channels behind the screen, and one for the surrounds. Sprocket holes on release prints had to be made smaller to fit the magnetic stripes. The cost of converting a theater for CinemaScope was approximately $ 5,000; many theater owners resented Fox's dictum of having to purchase the necessary sound system and high-gain screen to enable the lenses to project its films. Eventually these demands were lifted. Fox originally refused to release mono prints of CinemaScope films, and instead placed an optical track on four-track prints. Since the optical track was half-covered by magnetic striping, it was 6 dB lower in overall sound level and of poor quality. The 35 mm magnetic process fell into disfavor with many studios, who regarded the added cost of prints, complaints from exhibitors, and the cost of stereo dubbing as needless headaches. Problems with magnetic prints became self-evident. Prominent among these is their higher cost (approximately double that of conventional film), since each print has to be individually striped, recorded and checked in a theater. The extremely tight wrap of film against the heads makes for rapid wear, causing high-frequency loss. Eventually the magnetic oxide will become worn down, with drop-outs and scrapping of the print an obvious result. The third and most successful camera/sound system in the race was Todd-AO, first used on "Oklahoma", which opened October 13, 1955. Mike Todd, who was also involved with the production of This Is Cinerama, wanted a process that would give the same effect as |

|

Early Seventies: Two-Track Stereo | |

Eastman Kodak and RCA had begun work on a two-track stereo optical system in

1973. They were soon joined by Dolby Labs and its noise reduction and

theater equalization techniques. At the November 1974 meeting of the Society

of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Dolby's two-channel Stereo

Variable Area (SVA) soundtrack was first publicly demonstrated, using a test

reel re-mixed from the Dolby mono film Stardust. Eastman Kodak and RCA had begun work on a two-track stereo optical system in

1973. They were soon joined by Dolby Labs and its noise reduction and

theater equalization techniques. At the November 1974 meeting of the Society

of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Dolby's two-channel Stereo

Variable Area (SVA) soundtrack was first publicly demonstrated, using a test

reel re-mixed from the Dolby mono film Stardust.Release of Tommy in the Spring of 1975 coincided with the introduction of the CP-100 Cinema Processor for Dolby-encoded magnetic and optical stereo soundtracks. At this point development of the Dolby system moved to Hollywood. 1976 saw the mixing of the first Dolby Stereo optical film in America The River Niger. Later that year A Star Is Born took over the lead from Tommy in the release-print format championship by being distributed in six systems: 35mm four-track and 70mm six-track Dolby and non-Dolby magnetic prints, Dolby SVA, and standard Academy mono. The release of Star Wars in the spring of 1977 saw two significant changes in Dolby Laboratories' approach to film sound. First, the six-track spread from four-track masters would only involve adding low-frequency information below 200 Hz to channels two and four. Additionally, these tracks are used only when required to augment music and effects and, as the theater equipment contains low-pass filtering, are not Dolby encoded. According to Dolby literature, the purpose of this method dubbed "baby boom" - is "to subjectively extend the bass response of the theater sound system." (Altec A-4 loudspeakers, commonly found in 70mm houses, roll-off steeply below 80 - 100 Hz, especially as many theaters now have no room for speaker wings. "Baby boom" is designed to help compensate for this low-frequency deficiency.) The second change was the ending of Dolby's regular involvement with 35mm four-track magnetic prints, in October 1976, with the introduction of the CP-50 Optical Sound Processor. This unit cannot process magnetic prints, but still gives theater owners a simple and inexpensive method of exhibiting Dolby Stereo optical films. Thus, the success of Star Wars established the commercial viability of both the "baby boom" and SVA formats. Thirteen films were released in Dolby Stereo during 1977, a figure that increased by ten in each of the next two years until 1980, when over 60 films carried the Dolby logo. A few films originally released with Academy mono tracks, such as The Exorcist, and American Graffiti, were re-mixed and subsequently re-released in Dolby Stereo format. |

|

Dolby Stereo Film Sound | |

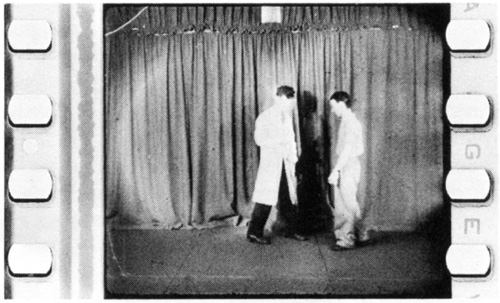

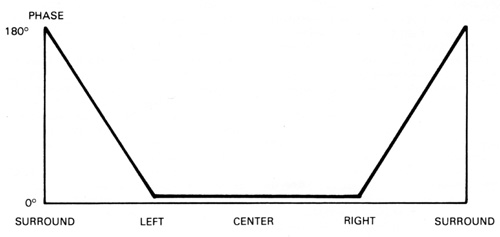

Figure 2: Phase/Orientation relationships for the Dolby Stereo matrix

encoding process. Figure 2: Phase/Orientation relationships for the Dolby Stereo matrix

encoding process.Beginning with A Star Is Born and ending in the Spring of 1979, Dolby SVA prints had surround information encoded using the Sansui QS Matrix, in addition to techniques designed to reduce crosstalk from the front speakers. The center channel had been derived by a logic circuit which analyzed the differences between the left and right track signals. Separation between channels was of the order of 6 to 8 dB. Hair and Hurricane were the first films to be mixed with a new "center channel and surround derivation card" which allows much greater separation between channels. The workings of the matrix will be discussed in detail below, but for now let's find out why a matrix is used in the first place, and why Dolby doesn't make a four-channel optical system. Dolby marketing vice president loan Allen: "The narrower you have the tracks, the closer you are to being at the mercy of what I call the 'laboratory glob factor' the dirt or whatever can happen to the track. As you reduce the size of the track you are fundamentally risking very surprising things happening in theaters. It would be nice to use discrete tracks, and have left, center, right and surround channels, but it's a darn sight safer to encode the material on two tracks." Other reasons stated include the fact that having more than two tracks means that printer misalignment and projector weave become more critical. Not only do two tracks have a better inherent signal-to-noise ratio than three or four, but loan Allen also considers them to be superior with regard to compatibility with standard mono projectors. It should be noted that two systems are currently being considered which indeed do have four discrete tracks: Vistasonic Sound, developed by Paramount Sound Systems, and Comtrack (which was explained fully in the February 1980 issue of R-e/p). Vistasonic Sound had its debut in December 1980 at special engagements of Popeye. Only five theaters two each in Los Angeles and New York, and one in Chicago played the film in the Paramount system. |

|

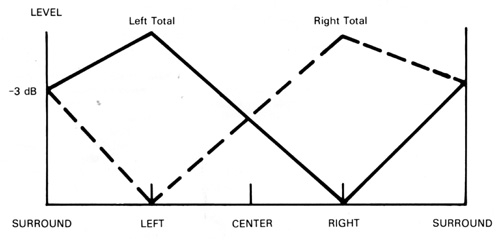

Level And Phase Relationships | |

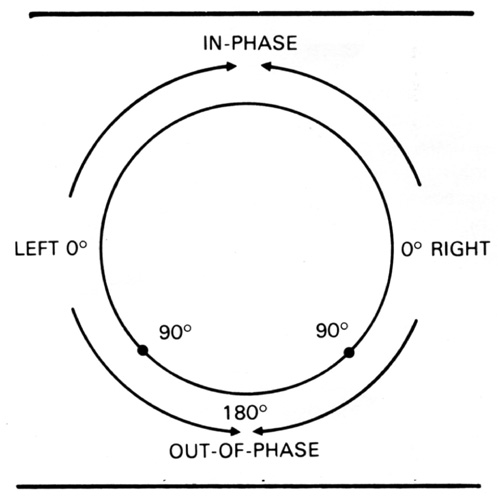

Figure 3: Level/Orientation relationships for the Dolby Stereo matrix. Figure 3: Level/Orientation relationships for the Dolby Stereo matrix.Don Digirolamo, Dolby sound consultant, explains: "If a signal is sent to the left channel, it will appear in the Left total (Lt) track at unity gain and in phase. Similarly, right channel information will appear in the matrix as Right total (Rt) at unity gain and in phase. Information in the center channel will appear in both the Lt and Rt at 3 dB below unity gain. It is not placed 6 dB down, however, which is where it would be to add up straight across, because if it added up at equal level the decoder wouldn't be able to tell left from right from center in terms of power, since there wouldn't be a discriminating gradient. "The surround information is recorded 3 dB down on both Lt and Rt, and phase-shifted so that one channel is plus 90 degrees and the other minus 90 degrees relative to the front information. The surround component to Lt, versus the surround component to Rt, is almost but not quite 180 degrees out-of-phase (see Figures 2 and 3). "Anything that is on Lt only becomes left-channel information, and anything on Rt only becomes right-channel information. Anything that is on both, in phase, goes to the front center, and anything that is out-of-phase between them goes to the surrounds. On playback, information placed in the center channel will appear at -15 dB on both sides. Anything placed into the left will be 15 dB down at the center, 'infinitely' down on right, and vice versa. "There is 'infinite' separation across the circle (Figure 4) so that center and surround are mutually exclusive, as are left and right. Problems begin when one is dealing with adjacent channels, because obviously there is not infinite separation between adjacent points on the circle. Separation varies dynamically with program material." |

|

Mixing For Dolby Stereo | |

Figure 4: Figure 4:Phase/Orientation relationships for the Dolby Stereo matrix, shown in polar coordinate form. A Dolby Stereo mix requires more of a dubbing studio than just a stereo console, golden ears and capable maintenance. The difference lies in the wide-range monitoring and the permission it gives the matrix to expose the slightest maintenance error. Studios with little experience of Dolby Stereo rely on Dolby's sound consultants to see that technical areas are up to snuff, and enable mixers to trust the mysterious box in the corner that is constantly analyzing their taste. According to Don Digirolamo, "A Dolby sound consultant ends up being the one person usually whose only task is to run interference between the labs, the studio, the product, the producer, Dolby equipment and what-have-you, in terms of the technical quality of the sound. On the engineering end, presumably the studio will already have the Type-A noise reduction. They will need to get 1/3-octave equalization for the monitor speakers, which usually comes from either a CP-50, 100 or 200 Cinema Processor, or from individual 1/3-octave equalizers." Although Bill Varney deals with Dolby Stereo from the console (Stage D at the Samuel Goldwyn Sound Facility at Warner Hollywood, where he is the lead re-recording mixer in a team with Steve Maslow and Gregg Landaker) and not the machine room, his engineering background and long list of Dolby films make him a capable judge of the system's technical parameters: "Pretty close is not OK with the Dolby process; everything has got to be dead on and there is no room for error in terms of equalization of machines or levels. In the Academy process you sometimes get a chance to hide bad dialogue and bad music. With Dolby you don't get that chance; it's all hanging out there. If something is wrong, you're going to hear it." All tracks of Star Wars were Dolby-encoded, but this was the exception that proves the rule, since usually only music goes to the dubbing stage encoded. Bill Varney would like to see this situation changed; "I would like to see everything Dolby-encoded the first time it is ' transferred to magnetic film; anything that you can do to cut the noise helps. The only drawback is the danger of having material recorded at various studios with different Dolby levels. Most often, though, the place that does the dubbing has also done the transfers. "However, it is not absolutely necessary to encode the tracks. I've heard people say, 'I'd love to do the final re-recording of my picture in Dolby, but none of the elements are Dolby-encoded.' People in this business still don't know what Dolby is all about. There are still people who think that it's some magic encoding process and if it hasn't been done, then you can't use the material." |

|

Mixing Through The Stereo Matrix | |

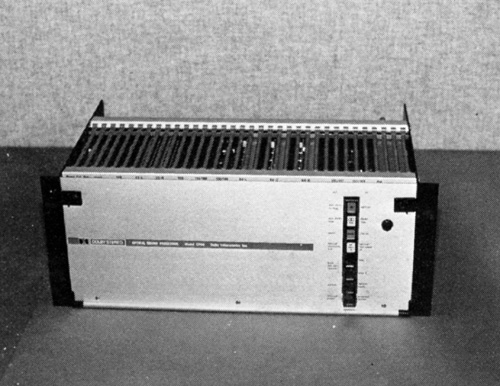

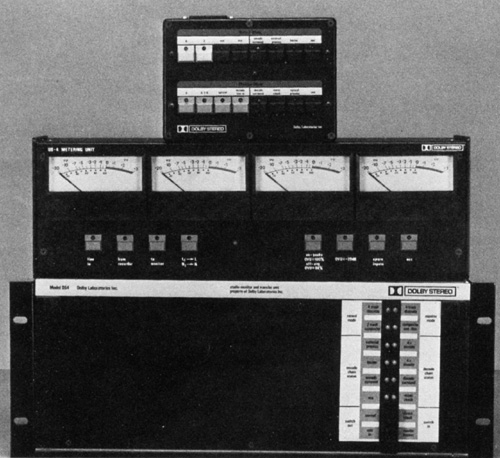

The Dolby DS 4 Studio Monitor and Transfer System comprises three units: a

processing system (bottom); metering unit (center); and remote control

(top). The system enables dubbing mixers to monitor the transfer and mixing

process at various points in the signal path from the original four-track

master tapes, through the dubbing console, to the optical or magnetic

soundtrack master. Four meters are provided for monitoring left, right,

center and surround channel levels; the meter ballistics can also be set to

either VU (average) or peak-reading. A variety of record and monitor modes

can be selected via the remote control unit. The Dolby DS 4 Studio Monitor and Transfer System comprises three units: a

processing system (bottom); metering unit (center); and remote control

(top). The system enables dubbing mixers to monitor the transfer and mixing

process at various points in the signal path from the original four-track

master tapes, through the dubbing console, to the optical or magnetic

soundtrack master. Four meters are provided for monitoring left, right,

center and surround channel levels; the meter ballistics can also be set to

either VU (average) or peak-reading. A variety of record and monitor modes

can be selected via the remote control unit.To assist in the dubbing of Dolby Stereo films, an encode/decode monitoring and recording unit, the DS-4, was introduced in late 1979. This portable unit allows mixers to hear exactly what will be reproduced in the theater; it encodes the four channels of information into a simulated two-track release print, and then decodes it back into four channels in much the same way it does in a theater. The flick of a switch will place into the center channel a combination of the left and the right tracks, remove the Dolby decoding, and insert into the monitor the Academy filter. In addition, the DS-4 contains a function whereby a stereo mix can be monitored discretely without the matrix to check how it will sound on 70 mm prints. Bill Varney: Grease, my first Dolby film, was monitored in a four-track discrete manner. In the early days, the Dolby representatives, who worked closely with us on the sound stages, had the attitude that we should do it this way because, basically, the matrix is going to recreate this same sound imagery once we get to the theater. When we finished that film and reduced it to the matrixed two-track stereo format, and decoded it back to four, I found that it was a completely different picture. The stereo width had narrowed down tremendously, among other things. We had to re-dub it and, by re-balancing, try to get back the width we had lost. "Monitoring through the matrix, we are now in the position to deal with all of the dynamics and spatial effects, and hear what will ultimately be heard in the theater. We can make all the compensations necessary to make the mix work and there is no guesswork. It's a simple way to go." Usually only a few 70mm prints are made for any film, and they play in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and other large markets.2 In these cases, the large majority of stereo prints will be in 35mm stereo optical; hence, the importance of monitoring through the matrix. In the spring of last year, however, Bill Varney found himself in a unique position during the mix of The Empire Strikes Back: "Ben Burtt [the supervising sound editor], the crew and I decided that since we were going out with over 125 70mm six-track prints as our initial release, the best thing to do was to make sure that those prints were going to work and work well, and to deal with the Dolby matrix later for the 35mm secondary release. So we monitored the film in a discrete format all the way and, once the six-track was done, went back and put it through the 4-2-4 monitoring. We were pleasantly surprised, and had to do very little in the way of correction; the picture moved into the Dolby Stereo mode easily. "The two areas where you have to be careful, and that are hard to predict, are the boom channels speakers two and four and, more importantly, the surrounds. The idea was to make the film work on the front speakers without any surrounds or booms at all. We mixed the film by recording on just channel one, three, and five. We then went back and added the surround channel and the boom on the other tracks. The advantage to that is that when the film goes out in Spearfish, South Dakota, and the surround speakers and boom channels are not working, at least you know as mixers and creative people that the film is going to play and play well with just the front speakers working." |

|

Surround-Channel Delay | |

|

Surround speakers are also a factor in determining 35mm and 70mm capability,

as Steve Katz, Dolby consultant to all early Dolby stereo films, explains:

"A delay is built into the Dolby Cat 150 cinema decoder card for a specific

reason: it minimizes the perception of breakthrough of information such as

dialogue from the front speakers to the surrounds. If the surround is

delayed by 60 msec., then it will arrive just after the front information.

The delay is adjustable from 20 to 100 msec., so you can match it to each

theater. In the days of discrete stereo mixing, they would print the

surround information with a second pass, delayed a frame-and-a-half, or 60

msec. That was considered a fair approximation, as most theaters are around

100 feet deep. "The rule of thumb is that sound travels about a foot per millisecond in free air, depending upon temperature, humidity, etc. So if you're 80 feet away from the screen with a surround speaker near your seat, and the same information is fed into the surround and stage speakers, the surround information will reach your ear in 10 msec., and from the screen speakers 70 msec., later. "You run into a problem when you plan to release the film in both stereo optical and 70mm which, of course, will not be played through the matrix. If you record your delay on the stage and with digital delay lines there's no reason to stagger the tracks then you will wind up with a doubling of the delay time on stereo optical prints. Which is the opposite of the original problem, in that sound will now come out of the surrounds much later than it will from the fronts. "I recommend that all Dolby films be monitored through the matrix, even if there will be a 70mm release. That way you can check that you have no problems with phasing, that the surround you're putting down is getting through, and that the pans are working. When you take the matrix out and listen discrete, it widens it out. If you're happy with what you have through the matrix, you'll be thrilled with what you have discrete. "If you monitor discrete, then put a delay in the monitor, but don't record it. When you make your 70mm printing master, you re-introduce the delay, and this time you actually record it on the surround track." |

|

Dialogue Mixing | |

|

An oft-repeated criticism of the Dolby Stereo system is that it emphasizes

sibilant dialogue. Here are two "explanations" of that problem. First, Don Digirolamo: "I rant when I hear that 'Dolby Destroys Dialogue.' The only way I can answer to that is by tracing a Dolby film through production. The music tracks have been recorded in 24-track, or three-track 35mm; the musicians are playing in a quiet environment and it sounds great. You take it to the dubbing stage and play it through the wide-range monitor and it sounds beautiful; everything is fine. "You have your effects, some of which are taken from production tracks, and you take a lot of care and get library effects that are wide-range. All of these little things go to make one effect sound right. You play them and they sound great. "Then you take your production dialogue, which has been recorded oftentimes with radio mikes buried in the clothing on the person somewhere, so that it has several layers of cloth between it and the person's voice. It usually picks up chest-cavity resonances, or whatever, and sound completely unnatural and equalized. There's a fair amount of background noise on the stage anything from camera noise to air conditioning to whatever. You record this and play it back on the dubbing stage through the wide-range monitor and it sounds like ... a lot of background noise, air conditioning, clothes rustle... "With the Dolby System you can hear that your effects and music are beautiful and clean.. . and that your dialogue is pretty nasty. In an Academy situation you take your beautiful effects and music and play them through an Academy filter. When you do that to your dialogue, too, it all sounds much more similar in quality. When you don't run any of that stuff through an Academy filter, the differences are much more apparent. Hence, the opinion that Dolby Destroys Dialogue. "I call the Academy filter 'The Great Equalizer,' because it makes everything sound the same. The Dolby System doesn't do that and consequently the dialogue stands out as the weak link in the chain." Steve Katz, in his role as the original Dolby consultant in Hollywood, had to face the same question, and here is how 'he attacked the problem on the dubbing stage: "I built a de-esser and found that by using high- and low-pass filters with gentle 6 dB per octave slopes, and shelving rather than peaking equalization, you can minimize the sibilance. I will take a pass with the de-esser on each generation, because you can take so much out at a time without dulling the whole track. "Sibilant distortion usually falls at around 3 kHz and 6 kHz, and on the Dolby track 3 kHz is as flat as a pancake. An Academy track is 2.5 dB down at 3 kHz, and 8 dB at 6 kHz. The thing is that many Academy pictures are incredibly sibilant the 3 kHz breaks through like crazy. "Some mixers are so crazed about stripping a bit of camera noise or hiss or hum that they are willing to destroy the sonority of the dialogue for the sake of a little noise. Meanwhile in the background there's a car crash or a thunderstorm!" |

|

Mono Compatibility | |

|

The soundtrack area of standard mono films and Dolby Stereo optical prints

are very similar. Both contain two tracks, which in mono are identical and

in Dolby contain Lt and Rt information. Thus Dolby Stereo prints are

physically compatible with standard mono projection equipment, and it was

originally claimed that they would play equally well in stereo and mono.

Experience has shown that physical compatibility is not sufficient, however.

As we shall see, the mix on the stereo tracks determines how well they will

play in mono. Lately, distributors have been increasingly interested in the economy of a single-inventory release that is, supplying only stereo prints to mono and stereo theaters. (Such films as Star Trek, The Empire Strikes Back, and The Jazz Singer are good examples of this sort of release.) Although mono mixes were made for foreign language dubs, stereo prints are in general domestic circulation. Compromises in dynamic range and stereo width must be made in the stereo mix, to insure compatible mono replay of stereo prints. Here are some thoughts on the matter, first from Bill Varney: "I find that when you play a Dolby two-track Stereo optical print on a mono projector, the sides tend to pile into the center. If in the dub you have a lot of high-energy material working out there on the sides, in stereo it may not in any way encumber the dialogue or whatever is coming out of the center, because of the spaciousness of what's happening. It might, however, do it in mono. "There also seems to be a severe loss in the high-end, and I notice a relatively large increase in the low end. These two factors tend to make it sound very muddy. The fact that you are working with a Dolby-stretched signal is not, generally speaking, quite enough to counteract the sharp Academy roll-off." Dolby film consultant Tom Scott notes the similarities between making mono compatible record and film mixes: "If your stereo film mix is intended to be mono-compatible, you have to follow somewhat the same rules that you do when you're making a mono-compatible stereo record. You need to be careful of anything placed exactly in the phantom center. For example, on a stereo record you may have the bass, snare drums, and vocal exactly in the center and everything else panned to various places across the two channels. When you add the two channels together, material that is in the phantom center will combine and be 6 dB louder electrically. This changes the balance of the phantom center information to the rest of the mix. "Center information will pop up in mono, which can actually help in films. In general, to get a good mono-compatible mix the dialogue needs to be a little louder in the mono theater; since dialogue is in the center, it will get louder when played in mono. Whether it gets loud enough for a good mono is the question. If you have common information on the two sides, it will try to come out of the center channel anyway; when you add them together that will also get louder." loan Allen feels that "what controls compatibility is not how low the lowest sounds are, but how loud the dialogue is compared to 100% on the track. The monitor level is tied directly into how loud the voices will be made, and how the effects and music are spaced into the room you have left over the voice. If you have set up your meters and monitors so you have only 3 dB left to go over the voice level, then the effects will be very low compared to the voice. If you have 20 dB to play with above the voice, then it will be 20 dB louder. By setting the monitor level lower, you force the voice higher. In other words, if your monitor is high, the dialogue is lower and your mono compatibility goes down." When played at the standard relatively soft level used in most mono theaters, low-level dialogue on stereo mixed with excessive volume range may be unintelligible. |

|

General Considerations | |

|

Like most R-e/p readers, many of the people working in Dolby's film division

have experience in the world of recording studios. Here's Don Digirolamo's

assessment of the differences in mixing styles between the film and

recording industries, and his opinion of how the Dolby matrix responds to a

standard album mix, and processes it into four channels: "If you take an

album mix and feed it as left and right into the matrix, it will take

anything that's equal in voltage and phase and feed it into the center

channel. This is usually kick drum, snare, bass and lead vocals. Left and

right stay left and right, and anything that's out-of-phase ambient

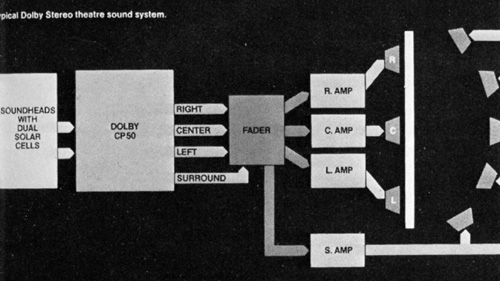

information will tend to go to the surrounds. "Mixing styles are quite different in the two fields, especially in terms of panning, equalization, echo, and loudness of the vocal. In a record mix, the vocal will certainly be there, but will be tucked back among the instruments. Movie music mixes tend to have the music considerably further back, and the vocals much more up-front. "There is a lot less echo used on a movie mix. A movie theater is a much larger environment than someone's living room, and will generate its own ambience for the most part. Most dubbing stages will also contribute their own ambience during the course of the mix. As a result, less actual reverberation in terms of tools or devices is added at the time. "In terms of panning, recording people will have a two-channel panpot, and they'll place, say, four left-to-right sources for a drum kit, at 10 o'clock, 11:30, 1 and 2:30. In terms of movie sound, things are assigned to specific channels much more, but drums will tend to be more in the center. If you spread it in the theater it will be 60 feet wide the largest drum kit in history which is not to say that it isn't done. But you have to be careful. "In terms of monitor EQ, music studios are usually voiced brighter, flat to 6 kHz, and rolled off 3 dB per octave in terms of pink noise out of the monitor. Film dubbing theaters and movie houses on the Dolby system are voiced flat to 2 kHz, and rolled off 3 dB per octave. "On a technical level, one of the things that music people never tend to do, but which film people always carry out, is to use pink noise as a frequency-response record. Generally speaking, recording studios would put 1 kHz for level, plus 10 kHz and 100 Hz for EQ adjustment. You get azimuth from 10 kHz, and those three points would be the only ones you could use to optimize frequency response. Whereas in film you tend to use a level tone, and pink noise for everything else. You can do azimuth and optimize the response of the whole chain with it. "Anybody who's recording music in a music studio that is going to end up as film product should send along pink noise, since it facilitates checking all the generations of transfers one goes through." Although the film sound business is in need of technical standardization in many respects, one area in which progress seems to have been made recently is that of monitoring levels. In the recording world there are no standards per se, but obviously product for AM radio will not have a wide dynamic range. In any event, the producer and engineer have no control whatsoever over the choice of playback levels.  The Dolby CP200 Cinema Processor will handle all current Dolby Stereo

formats, including two-track optical and six-track magnetic soundtracks, for

both 35 and 70-millimeter releases. The Dolby CP200 Cinema Processor will handle all current Dolby Stereo

formats, including two-track optical and six-track magnetic soundtracks, for

both 35 and 70-millimeter releases.When people go see a film, however, they pay money to have the sound set /or them, and compromises must be made with regard to level. Not only because of patrons who like films loud or soft, but also because of similar restraints to those that apply to TV and radio. Steve Katz explains: "The biggest danger in a theater with motion picture sound is the same one you have in mixing or broadcasting for car radios the actual environment has very little dynamic range. I define dynamic range in the theater as the distance between the little old ladies with umbrellas and popcorn noise. The danger is that the theater manager will find the loudest piece of music, bring the level down to where his patrons are happy with it, and half the show will disappear. "People who think, 'Ah ha, Dolby gives me 10 dB of noise reduction, why don't I take those 10 dB out on dynamic range,' pay the price at the theater. Because an optical track doesn't have the headroom and saturation capability of magnetic tracks it has hard clipping you must be very careful. You especially do not want dialogue to explode into the red, or over 100% modulation; peak meters are essential in this respect. They are very useful for film because of the nature of the environment: you're in a dark room, and have to concentrate not only on the faders in front of you, but on the cue sheets, footage counter and the picture on the screen." |

|

Multitrack Techniques | |

|

Mono mixes for motion picture are made on three tracks, with one each

devoted to dialogue, music and effects. Not only does this facilitate easy

repairs, as only one section needs to be repeated, but it also creates

minus-dialogue information for foreign language dubbing. Stereo mixes, on

the other hand, are almost always tied together on one piece of film. Of

course, minus-dialogue mixes must be made for foreign stereo and mono

release. A domestic stereo master is useless for such purposes, and all music and effects tracks must be re-mixed, -EQ'd, -reverbed, etc. Automated mixing is, of course, a help, but is unable to recreate the contribution of outboard equipment, at the very least. Bill Varney has given much thought to these problems: "On Empire we recorded our six-track master and on another recorder generated a four-track sound effects-only, by sub-bussing. We took that and added back music to create the stereo foreigns. Ultimately 1 would like to see us being able to use a 16- or 24-track format exclusively, where four channels would be designated for dialogue, four for music and four for sound effects, plus a few more for SMPTE time code and sync information. From that master we could ping-pong over all the various formats we use: two-track Dolby Stereo printing master; Academy mono; foreign minus-dialogue stereo, and so on. I almost feel that we could get as much flexibility out of the two-inch multitrack, as we could out of computerized mixing." |

|

Two-Track Master | |

|

Dolby recommends that final mixes be made four-track, and that a two-track

printing master be made for transfer to optical. According to Don Digirolamo:

"If you have to fix the two-track, effectively you have to have all the

elements up, and fix all four channels at the same time. Whereas if you're

fixing a four-track, and you just have to replace one line of dialogue and

there isn't any music or important effects, you can do just that one channel

alone." At the present time there are only four Dolby Stereo optical cameras in the world: Phil Boole Recording Services (PBRS) in Burbank, California; and one each in England, Japan and Germany. A few Dolby negatives are made for each film, to allow for mishandling during high-speed printing. It is recommended that sound-only test negatives and prints be made during re-recording to ensure the smoothest transfer to the optical medium, much as one cuts reference acetates during the disk-mastering process. Dolby decoding level of the SVA prints is matched in the field to a standard alignment film provided by Dolby Laboratories. The same film also contains pink noise to align the optical preamplifiers to flat response, which usually extends beyond 12 kHz. Alignment of Dolby 70mm prints is a trickier matter since, until recently, every studio that produced magnetic prints used different recording equalization. Therefore, a 70mm test roll containing pink noise and Dolby tone is a necessity for each feature. |

|

Conclusion | |

|

No recent motion picture system has risen as quickly as the Dolby Stereo

system, being elevated to a position of industry prominence within a few

short years. It is hoped that this article has made clear the reasons for

such growth. Now, for two closing remarks. First, loan Allen: "I am not interested in coming up with a soundtrack format that only sounds good in Hollywood or New York. We want to get stereo to as many people in this country at consistently good quality. The only way we can do that is to give the theater service engineers a format that they are capable of maintaining. Give them more than that, and we are all wasting our time. "All Dolby-equipped theaters are supposedly equalized to the wide-range monitor curve. A peripheral benefit is that not only do the loudspeakers sound better but, for the first time ever, it is possible to take a film from the dubbing theater, to a first-run house in Hollywood, to the boondocks, and it will sound the same in all three locations. We haven't gotten to that point yet, but at least the equipment makes the dream possible."  Bill Varney: "In the final analysis, Dolby is doing what it's supposed to do

make films sound better. It should make all films sound better. There is

no reason why any motion picture produced anywhere in the world should not

be released in this format. I don't see any reason why if it's a quiet,

dramatic film that the Dolby process can't enhance it even more. The music

sounds richer and more beautiful, the sound effects take on a more life-like

feel and the dialogue will just be that much brighter, crisper and nice.

There's really no argument against not using it." Bill Varney: "In the final analysis, Dolby is doing what it's supposed to do

make films sound better. It should make all films sound better. There is

no reason why any motion picture produced anywhere in the world should not

be released in this format. I don't see any reason why if it's a quiet,

dramatic film that the Dolby process can't enhance it even more. The music

sounds richer and more beautiful, the sound effects take on a more life-like

feel and the dialogue will just be that much brighter, crisper and nice.

There's really no argument against not using it." |

|

Footnotes: | |

|

1 Anamorphic lenses compress an image horizontally by a given factor

during photography, and expand it to the same degree when projected. Thus

the aspect ratio the relationship of the width to the height of the screen

is doubled. In this manner, material photographed with standard anamorphic

lenses (2:1 compression/expansion) is 2.35 times as wide as it is high,

versus the 1.17 aspect ratio of the image area on each frame. Fox's

Cinema-Scope lenses are no longer in use; the most popular anamorphic lens

systems today are Panavision and Technovision. 2 A 70mm print of an average-length feature film costs around $14,000, versus $1,000 for a standard 35mm print. 3 Printed at the head of The Last Waltz was the notice: "This Film Should Be Played Loud!" Reprinted from the February 1981 issue of Recording Engineer/Producer (Volume 12, No. 1). Larry Blake hails from New Orleans, Louisiana, and currently resides in Los Angeles. He is interested in pursuing a motion picture directing career, and is currently writing a book on the history of film sound. |

|

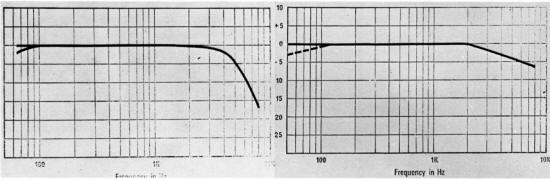

The Academy Curve versus wide-range monitoring | |

In 1938 the electrical monitoring curve shown in the left-hand figure was

established by Hollywood to organize all studios and theaters to the same

standards. Previously each studio used different high frequency roll-off to

combat the optical noise revealed by modern speakers. Because the study was

conducted by the Research Council of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and

Sciences, the response became known world-wide as the "Academy Curve." Click

the graphs, to see an enlargement Click

the graphs, to see an enlargementSince the days of CinemaScope, sound mixes for magnetic stereo release have been monitored without the Academy filter, although no specific curve was ever established. Dolby films since 1972 have used the curve shown in the right-hand figure, later standardized by the International Standards Organization (ISO) as the "X" curve in Bulletin 2969. The presence of 1/3-octave equalization in re-recording monitoring and in theaters allows the benefits of the extended curve to be realized, as Les Fresholtz, dubbing mixer at Burbank Studios, explains: "When you did a CinemaScope stereo dub, you would remove the Academy filter, but the speakers still had certain deficiencies in the room. These you would find and work against, knowing that the product wouldn't end up in another theater with those particular problems." Curve "X" of 2969 specifies a roll-off of 3 dB per octave above 2 kHz, when the theater is measured with pink noise. Because this test procedure will show the direct signal from a loudspeaker, plus the reverberation component from the auditorium, the actual direct response from the loudspeaker is closer to a roll-off of 1 to 1.5 dB per octave above 2 kHz; subjectively this means that the response is down about 3 to 4 dB at 10 kHz. Cinerama, except that the image would "come out of one hole." The result of the American Optical (the "AO" of Todd-AO) Company's work was a photographic system employing 65mm film whose frame size was 2.8 times the size of a standard 35mm frame, making for brighter, sharper images. Sound was mixed to six tracks, with five speakers behind the screen and, again, one channel for surround speakers. The 65mm negative was printed on 70mm wide Stock, the additional space being used to accommodate wide magnetic stripes outside the perforations. (This system has never used optical soundtracks.) From its inception, until 1970, this format was used on some of the biggest films Hollywood had to offer: Ben-Hur, West Side Story, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Patron, and so on. Its demise was caused largely by the studios' decision to no longer photograph in 65mm, but instead to blow up 35mm negatives to 70mm prints. The added expense of the large format approximately $ 200,000 for an average feature was not deemed necessary; since 1971 all films released in 70mm have been photographed originally in 35mm. The foregoing reasons, and the severe losses incurred by most studios in the late Sixties, resulted in fewer 70mm releases. As an economy measure, many 70mm films were mixed in four-track stereo. Information for tracks two and four was created by combining the center channel 50/50 with left and right tracks, respectively. Mixers of the period felt that this method was inferior to discrete six-track dubbing. We shall return to this matter in a different context later, but suffice it to say that from 1971 to 1977 almost all stereo films were recorded four-track for release in the four-track 35mm, and/or six-track 70mm magnetic formats. Dolby Laboratories' beginnings in the motion picture field paralleled the" growth of its A-type noise reduction: initial acceptance was confined, in the main, to Great Britain. Dolby noise-reduction had been used in the scoring of such films as Oliver! and Ryan's Daughter, with England's Rank/Pinewood Studios using the Dolby System to reduce noise build-up caused by generations of pre-mixes. Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange was the first film in which Dolby noise-reduction was used on all magnetic generations up to the final magnetic master. (The film was released with a standard Academy mono track.) Around this time loan Allen of Dolby began a thorough investigation into the possible applications of A-type noise reduction to film sound. It was quickly discovered that much of the bad reputation of optical soundtracks was a function of the practical use, rather than the abilities, of the optical medium. Prominent among these factors was the degree of high-frequency boost needed to counteract the steep Academy roll-off equalization, and the resultant distortion. The panacea for such "ills" of optical soundtracks lay in widening the bandwidth and using Dolby noise-reduction to counteract the resultant rise in optical noise. The first film produced with a Dolby-encoded soundtrack was A Quiet Revolution, which had been made to explain the system's benefits to exhibitors. At the time, in early 1972, the Model 364 Cinema Noise Reduction Unit was introduced to facilitate the playing of Dolby-encoded mono tracks. Optical playback is achieved by shining light through a slit on to the soundtrack and finally to a photocell. The width of the slit is directly analogous to the gap of a magnetic head: the narrower the slit, the higher the frequency that can be resolved. The slit can only be made so small before reducing the output to unusable levels. The Model E2 Cinema Equalizer was introduced in 1973 as a companion to the 364, providing compensation for the high-frequency roll-off in optical playback due to slit loss. The unit also included 1/3-octave equalization to improve loudspeaker response. Most sales of 364/E2 units were made in Great Britain and Canada. Approximately ten films were eventually released in Dolby mono. The obvious next step for Dolby would be the application of the same techniques to stereo prints, and in late 1974 The Little Prince was shown with Dolby-encoded four-track magnetic release prints. Although a few other films, including Nashville and The Song Remains The Same, would be released in this format, work was already underway on the design of a stereo optical track. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 05-01-25 |