Mixing Techniques for Dolby Stereo Film and Video Releases | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Larry Blake. From the June 1985 issue of Recording Engineer/Producer. Copyright © 1985 by Larry Blake. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Text retyped from Dolby Laboratories S85/3242/6599 | Date: 20.12.2015 |

|

Larry Blake will be publishing this article in

Spring 2016 in an anthology along with 35 other feature articles that he

wrote between 1981 and 2015, covering the span of film sound through that

era. At the same time, he will also be publishing an anthology of his

columns through that era, in addition to publishing the autobiography of

Murray Spivack, the Hollywood film sound great whose work graced a high

percentage of the films released in the first heyday of 70mm—Oklahoma!,

Around the World in 80 Days, South Pacific, Porgy and Bess, The Alamo,

Spartacus, West Side Story, Cleopatra, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, The

Bible, The Sand Pebbles, Doctor Doolittle, Star!, Hello, Dolly!, Patton, and

Tora! Tora! Tora! For information how to purchase these books, please write Larry Blake - Book purchase. |

|

Mixing Techniques for Dolby Stereo Film and Video Releases |

|

Todd-AO,

Stage A, October 1994. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Todd-AO,

Stage A, October 1994. Image by Thomas HauerslevAs of June 1985, over 600 films have been mixed in Dolby Stereo, averaging approximately 120 releases per year during the past two years. Along the same lines, the use of Dolby 70mm prints by major Hollywood studios has been steadily increasing over the past few years. (Almost all 70mm releases since 1977 have been in the Dolby "baby boom" format, with channels 2 and 4 — left-and right-center — used only for bass extension information below 200 Hz.) Since 1982 approximately 15 films per year have been released in Dolby 70mm prints, and by the end of last year the grand total hit the 75 mark. The wide release in the 70mm films such as Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (250 70mm prints in the United States and Canada), 2010 (200), Brainstorm (175), Return of the Jedi (150) and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (140) has brought the roadshow format into smaller cities and theaters. (There are currently over 6,200 theaters equipped with Dolby Cinema Processors worldwide.) It has become standard operating procedure for the largest screen in a new multiplex theater located in even relatively small cities to be equipped for 70mm Dolby presentation. As a result, approximately one out of four Dolby Cinema Processors sold is the top-of-the-line CP-200 unit, which in its basic form is equipped to process standard Dolby 70mm prints, and can be outfitted to play Dolby "split-surround" and "discrete" six-track 70mm prints with the purchase of additional Cat. 22 noise reduction and Cat. 64 third-octave equalization cards. This extra equipment adds approximately $ 3,500 to the $ 15,000 price of a standard CP-200. Much has been said of the ability of 70mm six-track magnetic prints to give moviegoers a loud and "visceral" experience. Reality, though, imposes the same limitations on 70mm six-track prints as it does on two-track, four-channel Dolby Stereo optical releases. Such factors as sound system headroom, theater noise levels, and the intolerance of "little old ladies" to loud sounds conspire to bring the dynamic range of 70mm mixes closer to those expected of 35mm Dolby Stereo optical. | More in 70mm reading: Mixing Dolby Stereo Film Sound "In 70mm and 6-track Dolby Stereo" Presented in 70mm Dolby Stereo Dolby CP100 Cinema Processor Teccon Precision Magnetic Recording Heads Internet link: • Swelltone Labs 400 Lafayette St. Suite 120 New Orleans LA 70130-3349 USA Work: (504) 299-0082 • dolby.com |

Stereo Optical Versus 70mm | |

|

Dolby marketing vice-president loan Allen notes that the big difference

between 70mm and 35mm mixes is "not the overall dynamic range. What happens

on a 70 is that an occasional peak will get through that is louder on a

simple peak basis. The median levels of the loudest music, effects above the

dialog is probably very comparable to stereo optical. It's just that stereo

optical is a hard-clipping medium; you cannot go over 100%." Until recently, Max Bell served as a Dolby film consultant to the Hollywood community. He believes that the biggest factor in regard to the play-ability of any Dolby Stereo mix — 35mm or 70mm — is the probability of low-level playback. "The most common mistake [in a 70mm dub] is to mix to a wide dynamic range, resulting in a very loud mix. These people [directors and mixers] are later upset that it won't go to optical, when in fact it is unplayable even if you are running six-track double system. The dynamic range is just too wide. "Most theaters run the fader between 80 and 82 for both 35mm stereo optical and 70mm six-track magnetic — it is down 4 dB for every movie. [Dolby playback level is supposed to be set to 85 dB/c, slow, per channel, for 50% modulation.] Theater managers set it for the loudest music and effects. Every theater I go into is playing the movie too quietly — certainly quieter than the dubbing theater where the film was mixed. If you take that into account, there is plenty of headroom in stereo optical. And if you were to monitor [during a mix] at a lower level [than 85 dB/c], you would have a ridiculously tight dynamic range, not to mention throwing away 3 dB of headroom on the film. There is no way around it as long as theater managers are turning faders down." Bell had a preview in a theater a few months ago where he "had to walk through another theater in the complex to get to the projection booth. That theater was playing a Dolby film with the fader down 5 dB. I had them turn it up and ended up having a row with the manager. He said that the music 'stingers' were too loud. When he turned it down, it sounded like Muzak. Naturally, I didn't try to discuss the subtleties of dynamic range with him; I said that the dialog was being lost. He said, 'I don't care; it was too loud.' "While this film was being mixed, the director complained that he could not get as wide a dynamic range on the optical as he had wanted." | |

Monitoring with the Dolby Stereo Matrix | |

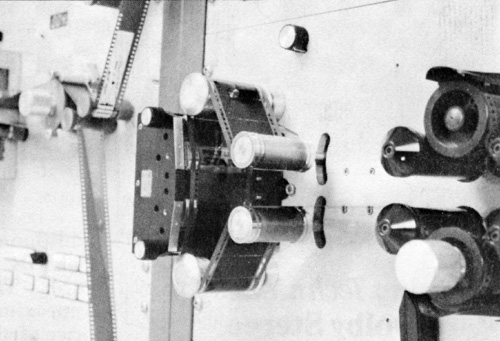

Closeup detail of Teccon Sendust 70mm headblock. (At left is

six-track printing master.) Closeup detail of Teccon Sendust 70mm headblock. (At left is

six-track printing master.)As many readers may already know, the 35mm Dolby Stereo system involves the matrix encoding of four channels of audio — left, center, and right behind-the-screen channels, plus surround — onto two Dolby A-encoded optical tracks, designated Lt (Left total) and Rt (Right total). In the movie theater, after noise reduction decoding, matrix decoding is handled by a Dolby Cat. 150 card that converts the two tracks into four speaker channels, thus completing the encode/decode 4-2-4 process. The behind-the-screen channels are equalized to the wide-range ISO "X" curve (flat to 2 kHz, 3-dB-per-octave roll-off after that) using third-octave equalizers. In the early days of Dolby Stereo there was much discussion about monitoring the mix through the 4-2-4 matrix. Many mixers, accustomed to the four-track mag format (with four magnetic stripes on a 35mm release print), resented having to adapt their mixing styles to a matrix-encoding technique. However, sensible minds prevailed, and today there is no argument as to the wisdom of hearing what will happen to the mix when decoded in neighborhood theatres. | |

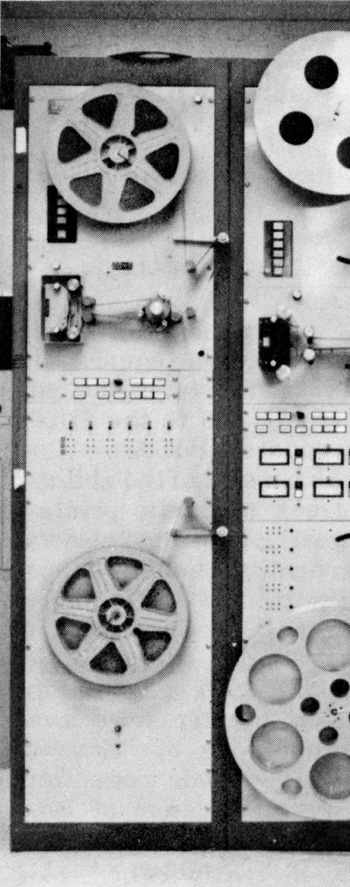

A custom Magna-Tech 70mm sounding channel at Warner Hollywood Studios. A custom Magna-Tech 70mm sounding channel at Warner Hollywood Studios.Briefly, these are the steps involved in producing a Dolby Stereo mix today: • Dialog and sound effects are pre-mixed to three- or four-track 35mm fullcoat. Music is usually recorded multitrack, and mixed down in a standard recording studio to 35mm three-track (described below). • The final mix is recorded as separate stereo left-center-right-surround (LCRS) dialog, music and effects "stems," either on multiple pieces of 35mm mag or on a multitrack recorder. • The stereo DME stems are combined onto a two-track Lt-Rt "printing master," which will be transferred 1:1 to an optical negative for use in making 35mm stereo optical prints. (Later, this two-track mix is also used for stereo home video release.) • If the film is to be released in 70mm, the stems are used to produce a six-track "baby boom" printing master. During this step, low-frequency information, usually only sound effects, is added onto channels 2 and 4. (The left-center-right speakers are channels 1-3-5.) The six-track printing master is copied in real time to each 70mm print. One of the practical benefits of Dolby Stereo, taking into consideration both 35mm stereo optical and 70mm baby boom, is that four-track master mix can be easily converted "down" to a two-track Lt-Rt printing master, and "up" to a six-track printing master, with boom information added for channels 2 and 4 on a 70mm print. Since most major studios are recording their master mixes as separate four-track music, effects and dialog stems, the dynamics of each section can be separately controlled during the print mastering step, which usually takes no more than two days. As a rule, the pre-mix, the final mix and, of course, the two-track printing master are all monitored through the 4-2-4 matrix, utilizing a Dolby DS-4 monitoring and recording unit. However, there is often a question of how much emphasis should be placed on the constraints of the matrix when the release involves a large number of 70mm prints. One of the key issues is stereo width: either it will be exaggerated in 70mm if the film was mixed with the matrix inserted into the monitor chain, or it will be too narrow in 35mm stereo optical if the mixers only monitored discrete, in anticipation of the 70mm release. David Grey, Dolby film consultant in Los Angeles, warns mixers against neglecting to check a mix through the matrix: "If you are going to do a multiple release [35mm and 70mm], and you mix discrete all the way through, my opinion is that you will get an extremely narrow, very compromised stereo optical, because you can't make a mix wider once it is narrow. And if a pan doesn't work, it doesn't work; you won't be able to redo it. "Our approach has been to keep the matrix in the line: do all your pans through it and get it as wide as you need it, knowing that you are not putting any matrix encoding onto the four-track track master. You are mixing in relation to the monitor. What is sitting on the track is, if anything, perfect in terms of width. In other words, nine out of 10 times you want it a little bit wider than the matrix is capable of giving you. It will widen out when you play it discrete; probably too much. It's very easy to bring it back in; it's virtually impossible to widen it." | |

Theater Alignment of 70mm Prints | |

The Dolby DS-4 meter bridge. The Dolby DS-4 meter bridge.Two-track and six-track Dolby Stereo printing masters are always A/B'd with test prints to check the transfer quality. In the case of the two-track Lt-Rt, a stereo optical negative is "shot" from the printing master, and then a sound-only print is made from that negative. With 70mm Dolby Stereo, the six-track printing master will be transferred to a striped print of the film. Often the blow up (no films are photographed in 65mm these days) is not ready by the time the six-track mix is finished; in these cases a 70mm print from another film is degaussed and is sounded for this test procedure. The major Hollywood facilities that sound 70mm prints observe the same equalization and level standards, in spite of the fact that there are no published standards for the 70mm six-track format. Currently, the "zero" VU reference flux is 185 nanoWebers per meter, and 35-microsecond equalization is employed. Until 1983, most 70mm printing was done at a reference flux of 90 nWb/m. Tests by Lucasfilm, Twentieth Century-Fox and Warner Hollywood for Return of the Jedi lead to the establishment of the 185 nWb/m flux level, 6 dB above the previous standard. | |

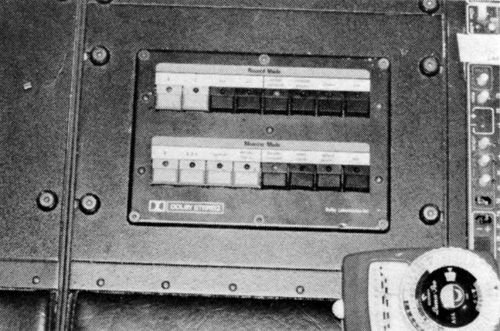

Remote control enables

recording and monitoring of the 4-2-4 matrix-encoding process used to

produce the Lt-Rt Dolby Stereo mix. Remote control enables

recording and monitoring of the 4-2-4 matrix-encoding process used to

produce the Lt-Rt Dolby Stereo mix.Such standardization was made possible largely because of the development, by the Los Angeles facilities Film Processing Corporation (FPC) and Magna-Crafts, of improved magnetic stripping for 70mm prints. There is general consensus in the industry that the three-percent harmonic distortion point is not reached until 15 dB over 185 nWb/m, headroom which is comparable to that of 35mm mag fullcoat mastering stocks. "Your distortion is going up more, but the signal will get there. We've frequently seen 15 dB above 185 without perceptible heavy distortion," says John Bonner, chief engineer at Warner Hollywood Studios. Recently, great strides have also been made in standardizing the equalization of 70mm printing. Bonner notes that "five or six years ago we were radically far apart — you'd see a 10 dB difference on the high end." Before a roll is sounded, industry s.o.p. dictates that it has to be checked for bias requirements and striping consistency, the latter being checked by recording pink noise and observing the results on a third-octave realtime analyzer. "If the striping is slightly thin, you will get what looks like an increased high end," says Bonner, "although I think it is really a decreased mid and low end. Every roll must be checked." To aid theater service technicians in aligning the mag pre-amps in theaters, rolls of pink noise and Dolby-level tone are sent with each print. In previous years this was mandatory because of the wide level and equalization differences among 70mm sounding facilities in Hollywood. The situation has changed today, and David Grey says that "you can use the pink noise from any studio to set up any 70mm print which came out at Christmas." | |

Mixing for the Optical Medium | |

|

Since late 1979, all Dolby Stereo mixes have been monitored and recorded

using a Dolby DS-4 unit to simulate the effects of the Cat. 150 cards used

in Dolby Cinema Processors. Throughout the pre-mixing and final dubbing, the DS-4 is used to check the effect of the matrix on stereo elements and panning. The unit must be present during the recording of the encoded two-track printing master from the composite four-track master (or, in some studios, from separate stereo dialog, music and effects four-track masters). The Dolby DS-4 unit has a monitoring function called "optical process," which is designed to give mixers both visual and aural indications of what will happen when the two-track mix is transferred to a stereo optical negative. First, the optical process mode limits response to that of the Dolby Stereo optical medium — approximately 25 Hz to 12 kHz. An optical clash simulator also provides an aural approximation of the effect of exceeding 100% modulation. For the eyes, there are two lights on the front panel of the DS-4 — "yellow" means that you have been in clash for 10 milliseconds or less, and "red" that you have been in clash for over 100 milliseconds. Grey regards the optical clash lights as "the definitive benchmark. The yellow light is in effect telling you that you are very close to clipping. In fact you are in it, but you won't hear because it is generally accepted that it takes 10 milliseconds for the human ear to hear distortion. The red light means have been in clash for 100 milliseconds or more, and you will hear it distort. "I can't count the number of times I have been called in and a mixer has said 'That button makes it sound like crap.' I say 'I know it makes it sound like crap, that's why it's there; that's the reality. "I know,' they reply, 'but it sounds awful. I had to take it out it was so bad.' "You won't believe how many intelligent people do that because they don't understand that this is what's going to happen inside the [optical] camera." Along these lines, John Bonner talks of the most common problem he faces when shooting a stereo optical negative: "I'm surprised at the number of print masters that we get where the people who mixed it don't seem to know where 100% is; they don't appreciate the 100% optical clipping point. When an optical track exceeds 100% there is nasty clipping, and they should be aware that the track is going to clip exactly 6 dB above that reference tone. We really don't care what that level is — 185 nanoWebers, 250, etc. — as long as that is the Dolby-encode level, and that they expect it to clip exactly 6 dB above it. That's all we're interested in. If we can't fit the track in, then we have to decode the print master and encode again so that the Dolby level on the optical negative is 6 dB below 100%. Each master must also be accompanied by pink noise, which we use for azimuth and EQ alignment." The above discussion has referred to, for the most part, lack of concern over the distortion and compression due to excessive levels. David Grey says that a common problem is that little attention is paid to what will fit to optical in the four-track stage (pre-mix and final mix). "You can't have something that is playing at 90 dB and pull it down to 80 and expect it to sound the same," he offers. "Not only does your frequency response subjectively change, but you change the dynamic range, which means you change the whole feel. If people stayed closer to what is possible on optical from the get-go, it would be a tremendous help." Nevertheless, he feels that the "optical process" switch on the DS-4 control unit should be kept off when making four-track mixes for a film that definitely will have a 70mm release. "There is no sense in keeping something back if you know you are going to go 70, although I obviously would like levels reasonably close to optical limits." | |

Mono Compatibility | |

|

The question of whether or not Dolby Stereo optical prints are compatible

with mono playback is no longer an issue in Hollywood: Six years and

hundreds of films have proved that mono compatibility can be achieved,

though often at the expense of compromising the stereo mix. Again, the

emphasis is on the playback level, although this time the focus is on the

dubbing stage, and not the theaters. "The key issue, more and more," says loan Allen, "is that it is the monitor level which affects [mono] compatibility to the greatest extent. The old problem in film mixes was that the director and the dubbing mixer would enjoy playing it loud in the dubbing theater, not realizing that the music and effects were loud, and that you always set the dialog level to match the action on the screen — the sensible dialog level for the 'size of the heads.' In other words, regardless of whether the loudest music and effects are 100 dB or 90 dB, the average dialog level will always be around 85 dB. "When the film gets to the theater, they set the fader by the loudest sound, and, as a result, the dialog will go down very much if the mix has a wide dynamic range. In stereo playback you might get away with it, but in a mono theater [to replay a Dolby Stereo print properly] the dialog really has to be up at between -6 and -10 all the way through to be intelligible. Of late, the art of getting a mono-compatible stereo mix has gotten much better." If while making the Lt-Rt Dolby Stereo two-track printing master the director and dubbing mixers decide not to compromise the stereo mix to allow for compatible mono playback, a separate mono mix will be made for exhibition at non-Dolby theaters. This is easier said than done, since the existence of two types of prints —Dolby Stereo and Academy mono —makes life much tougher for the studio exchanges that have to distribute the prints to hundreds of theaters. In fact, the possibility (some might say probability) of a non-mono-compatible Dolby Stereo print being sent to a mono theater, or an Academy print going to a Dolby house, is the prime reason that most (80%) Dolby Stereo films are released single inventory with mono-compatible mixes. Films with a very large number of prints, such as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1,500 and 1,900 35mm prints respectively in U.S. and, Canada), are almost always released single inventory because print placement problems are greatly magnified. Thus, almost 95% of the prints of Dolby Stereo releases are mono-compatible stereo prints. Single inventory is of greatest significance when replacement reels are ordered: exchanges often store films by reel numbers, and not by print number, which might indicate the soundtrack format. Thus there is a 50-50 chance that the print that is shipped will be the print that is needed. Still another way of looking at the issue is the fact that in 1985 almost all major first-run theaters in the U.S. are equipped with Dolby Cinema Processors. In addition, the attention devoted to sound in theaters that haven't converted to stereo playback often leaves much to be desired. loan Allen: "The deviation from any kind of standard in the [non-Dolby] theaters is much wider than the difference between a mono-compatible Dolby Stereo print and a real Academy print." | |

Optical Bass Extension | |

|

One of the most intriguing products that Dolby Laboratories offers the

film-sound world is the CN-160 optical bass extension card for Dolby Cinema

Processors. The 160 extracts low-frequency information below 100 Hz recorded

on the two tracks of a 35mm Dolby Stereo optical print, and feeds it (in a

70mm-equipped theater with five speakers behind the screen) to channels two

and four or, preferably, to a separate amplifier/sub-woofer combination.

This card is standard in a CP-200 and can be installed in a CP-50. (It

cannot be used in a CP-100 Cinema Processor.) In its simplest form, optical bass extension can be thought of as a way to help 35mm Dolby Stereo optical prints sound more like 70mm Dolby Stereo prints, since the information that both send to loudspeaker channels 2 and 4 (or to a subwoofer) is very similar: low-frequency music and sound effects. While this sounds very good in theory, mixers have found that occasionally too much dialog will bleed into the bass extension channel, resulting in Decreased dialog intelligibility. This points to the primary difference between 35mm and 70mm bass extension: in 70mm, the extra low-frequency information is selected and monitored by the mixers. While problems can arise by the 70mm bass extension information being played too loud, at least crucial dialog will not directly be affected. "I would be the first to admit that, set up badly, [optical bass extension] can muddy the dialog and cause room tone ringing," says Allen. "It's a dangerous weapon in the hands of an incompetent installer. Correctly set up, it's a thing of elegance and joy. "First, it has to be set up so that it's not excessively loud. In addition, the 160 board has a tuning circuit in it so that you can avoid the most bothersome peaks which would also make it too loud. "Finally, there is a very sophisticated circuit in it that reduces the level of any low-level spurious, unwanted rumble components. "So, the only thing that gets through when it is working properly is stuff like tympani, gunfire and material that is obviously intentional. I set it up by the book, and then I raise the level of the boom to where it does muddy up dialog, and then reduce it [the boom level] about 3 dB below that point. I'll usually find that I'm back at the book setting again, and I know that I have a 3 dB margin against the chance of it affecting the dialog quality. "Switching it in and out has a radical effect, and yet when it's in, if you're not doing an A/B, it just sounds good. You're not conscious of sudden bass thumps all of the time. It sounds as it should, which is as if the loudspeakers are extending to a lower frequency." Reprinted with permission from the June 1985 issue of RECORDING-Engineer/Producer. © 1985 Gallay Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 05-01-25 |