The Entire Development of the Cinerama Process |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Fred Waller, 31.03.1950 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

|

March 31, 1950 Mr. W. L. Laurence 541 East 72nd Street New York 21, N.Y. Dear Bill: As you and I agreed over the telephone, I'm going to tell a more or less chronological story of the entire development of the Cinerama process. It's not a short story but I'll try to keep it condensed. My work on the process started many years ago back at Paramount. I was doing photographic research and was looking into various inventions which were submitted to Paramount to see if there was anything useable or worth experimentation. I found little which was useable but my experience did reveal one thing which was significant later on. That was that wide angle pictures seemed to be more third dimensional than standard pictures. Later, when I took over Paramount's trick film department, I had the first 25 millimeter lens made. Though this lens gave a wide photographic angle and a more real-looking picture, it did not afford any wider projection angle. None of the processes of the day used a screen of sufficient angle to show what dramatic improvement could be made with the use of peripheral vision. |

More

in 70mm reading: mr. cinerama The Birth of an Idea Cinerama Goes to War Adding the Sound to Cinerama This Cinerama Show Finding Customers for a Product in70mm.com's Cinerama page Internet link: Ralph Thomas Walker 1939 World's Fair Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker William Leonard Laurence, science editor emeritus of the New York Times, was the only reporter on the story of the atomic bomb. He was at Trinity, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. |

First Experiments |

|

|

Due to the pressure of production work in

the east, and of the trick film department which I headed, I could not

continue my experiments at that time. It was years later before work

commenced again, when I was asked to see Ralph Walker, the New York

architect, who was interested in a new type picture presentation for use

at the New York World's Fair. He suggested projection on the inside of a

spherical surface with several projectors. This suggestion recalled my earlier experience of the dramatic effect of the wide angle picture. But no one before, to the best of my knowledge, had thought of projecting on a curved screen and if possible, increase the angle so as to include most of what the human eye sees? This might be the first practical step towards depth and realism in picture projection. So it was that in 1937 I started on some experiments to learn something of the characteristics of third dimensional vision. Earlier I had become convinced that the use of stereoscopic vision could not practically be included with wide angle vision. So first I set out to determine just what effects stereoscopic vision had in helping me to place myself in space. I took a long peaked fisherman's cap, hung a long piece of black paper around the peaked visor, cutting two small holes in front...thus limiting my sight to the central foveal area and allowing me to see an angle a little over one degree. This is the area of stereoscopic vision. I found that even though this allowed me to pick up objects from a table with ease, I could not navigate around my house without bumping into chairs, door jambs, etc. The next step was to enlarge these holes to allow the angle seen on a regular motion picture screen and I found that this was very little better than when I was limited to the stereoscopic angle. I still had no real perception of depth and environment. Next, I reversed the experiment, hung two small black circles on the peak of the cap, leaving all the rest of the vision open. With a little practice I was able to stare directly at the two black lines with my central vision and found that I could navigate perfectly, even though I was without the help of stereoscopic sight. I carried this experiment still further by driving my car around my driveway, staring at the two black discs and letting my edge-vision guide me in my position on the road clearances, etc. Since I found no trouble in doing this, my conclusion was that if we were going to have pictures which would have realism, we would have to include most of the peripheral angle. I concluded also that if we left out the stereoscopic vision, there would be little lost in realism and sense of depth perception or third dimension. After developing these experiments further, Mr. Ralph Walker and I decided to secure and adapt apparatus to make a practical demonstration. |

|

Making the first Picture |

|

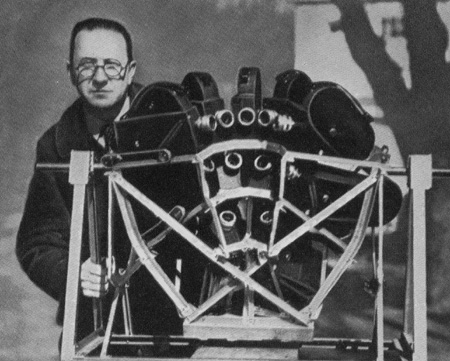

The first demonstration apparatus was made

with eleven 16 millimeter cameras put together on a single frame and driven

by a single motor. The first demonstration apparatus was made

with eleven 16 millimeter cameras put together on a single frame and driven

by a single motor. After many months of hard work, I completed and eleven camera unit and photographed scenes around my own place with people moving. Then I put the camera on my car and took a running shot down one of the roads in Huntington. We then needed eleven projectors for showing these pictures. When I had four of them connected, a good friend of mine, Dr. L. A. Jones, optical physicist of Eastman Kodak Company, came out to my home in Huntington. In the barn was a six foot radius spherical screen and the four projectors. That evening, we projected these fragments of the picture of the trip down the road. It was so startlingly real and one had such a sense of environment and spatial relationship that Lloyd [Dr. Jones] said, "Fred, you have demonstrated to me fully all that you and I often discussed." As a matter of fact, Dr. Jones was so convinced that I had the answer that it was three models later before he took the trouble to come again to Huntington to see the progress being made. |

|

A Screen Too Wide |

|

Nine months later, I had the eleven projectors

mounted and synchronized. We projected the image on the section of the

sphere 75 degrees in the vertical and 130 degrees in the horizontal, this

sphere being of a 6-foot radius with a continuous surface. When we projected

our pictures on the full screen, the effect was startling. The realism was

much greater than we had anticipated. Unfortunately, however, we had made a

mistake. I had overlooked that fact that in photographing 130 degrees in

width, I could not get away from including the opposing lens at two edges of

the picture. We proceeded to experiment with reducing the angle of vision so as to get

away from photographing the lenses of the camera itself. The amount cut down

in this particular set-up was 7˝ degrees on each side. When this was done, I

found that I had lost little of the effect of third dimension. So I

rearranged the projectors and made my first series of pictures to project on

a screen 75 degrees high and 16 *) degrees wide [this seems wrong – should it

be 116 degrees or 160 degrees? – BG/ed]. These pictures were made in

Rochester, New York, with the assistance of some of the Eastman Kodak

engineers who were interested. I also made some scene on Long Island and

others on my yawl. The first demonstrations ever made to invited guests were

in a rented office at 101 Park Avenue, in New York, where Ralph Walker's

office is. We showed these to perhaps one hundred people by invitation in

the latter part of 1938. Mr. Laurance Rockefeller attended one of these

showings at that time and became interested in the process. We proceeded to experiment with reducing the angle of vision so as to get

away from photographing the lenses of the camera itself. The amount cut down

in this particular set-up was 7˝ degrees on each side. When this was done, I

found that I had lost little of the effect of third dimension. So I

rearranged the projectors and made my first series of pictures to project on

a screen 75 degrees high and 16 *) degrees wide [this seems wrong – should it

be 116 degrees or 160 degrees? – BG/ed]. These pictures were made in

Rochester, New York, with the assistance of some of the Eastman Kodak

engineers who were interested. I also made some scene on Long Island and

others on my yawl. The first demonstrations ever made to invited guests were

in a rented office at 101 Park Avenue, in New York, where Ralph Walker's

office is. We showed these to perhaps one hundred people by invitation in

the latter part of 1938. Mr. Laurance Rockefeller attended one of these

showings at that time and became interested in the process.On November 3, 1938, The Vitarama Corporation was formed to develop the process. The stockholders were Mr. Laurance Rockefeller, the architectural firm of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, and myself. |

*) Here

is the logic of questioning the 16 degree figure: He [Waller] started with 130 degrees and found that too wide so needed to narrow the field. He says he removed 7 1/2 degrees each side so this makes 15 degrees. 130 degrees minus 15 degrees = 115 degrees, but due to tolerances etc. this may explain the 116 degree figure. Brian Guckian, Dublin, Ireland |

Other Became Interested |

|

|

At that time too, a group of engineers for

Eastman Kodak came to see a demonstration. Among them was John Capstaff who

has as sound knowledge of photographic images as anyone I know. He was

thrilled by the third dimensional effect but called my attention to the fact

that I was getting bad degradation of image due to internal reflection on

the screen. Though I had appreciated this to an extent, I didn’t realize how

important it was. John made the statement that if I could eliminate this

degradation of the image, I would then have a truly remarkable picture to

look at. That afternoon I started to work on geometrical methods of building

a screen with separate facets which would eliminate the internal reflection.

I worked out six methods of approach and filed patents for them. At this point, our work was moved to a garage on West 55th Street, New York, which Mr. Rockefeller made available, rent free. This was certainly an important contribution to a young struggling company. A screen with a louvered surface was then built in the form of a section of a sphere. The flat surface of each louver was made to line up with a point at the bottom of the spherical screen. After further development work and different arrangements in the camera we found that we had actually improved the third dimension quality of the picture, at the same time having eliminated the degradation of the image. |

|

Shows for the New York World's Fair |

|

Time and Space Pavilion Time and Space PavilionPerhaps it should be added here that about this time...late 1938..I was asked by the Eastman Kodak Company to work with them in the development of a show for the New York World's Fair. The hope was, of course, to dramatize the effectiveness of color picture results with the use of Kodachrome films. To achieve this, we devised a panoramic arrangement of eleven screen projections of Kodachrome slides. The effect was extremely successful. Actually, by the time the Fair was over, the Kodak show had drawn more attendance than any other commercial exhibit there. Also at the fair I produced a show using both motion and still pictures to get a third dimensional effect. This was done for the American Museum of Natural History and was called, "Time and Space". I also approached the idea in the ten columns of marching figures on the inside of the Perisphere at the same fair. |

|

Work on a New Sound System |

|

|

As work continued on the motion picture

process, we felt we had to study the possibilities of a new sound system. We

had to have effects which were as third dimensional for sound as we had

achieved for pictures. Our first work in sound was done with three parallel cuttings on a single disc, each of the three grooves being supplied by sound from a separate source and the sound from each of the three pickups being amplified and fed directly to three loudspeakers. This setup proved to be another real improvement, not only in the sound itself, but in total effect. For the first time we had seen a wide-angle, three dimensional true perspective picture with realistic sound which enhanced the effect. The great deal of production research followed with this equipment. Scenes were made in black and white and in color and of different types of subjects from different angles. The process reached the point where we were about to start production for theatrical release, intending to have out first showing in the Center Theatre. At this time war broke out in Europe. It was obviously a very poor time to bring out a new motion picture process. I decided to take a cruise on my yawl for a much needed vacation. This was in early 1940. |

|

The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer |

|

|

Just as I was about to leave, an old friend,

who had retired from the Navy, came to see me and made a suggestion which,

as it turned out, carried the process many steps further along the way. My

friend had majored in gunnery at Annapolis years before and had had broad

experience in it. He said that in his opinion the Cinerama screen had all

the essential qualities needed to present a moving target for a flexible

gunnery trainer to teach machine gunners to shoot down aircraft. The problem

was to work out a technical apparatus to determine the correct point of aim

and let the gunner know when he was on that point. In motion picture trick work, when you cannot solve a problem the regular way, you see how it should work out backwards and that approach solved the gunnery problem. That is, we started with the bullet in the target, put the bullet back into the gun and put the target back to the point it was at when the trigger was pulled. The more we thought this plan over the better it seemed to us. I went to work to adapt the equipment for a baby model of the gunnery trainer. We used the experimental screen already built and the eleven camera set up. The Army Air Force cooperated with us in allowing us to take pictures for demonstration purposes. These were made at Mitchell Field in the fall of 1940. I won't go into the subject of the Gunnery Trainer here, for the story of its development and its operation are included in a blue folder entitled "Waller Gunnery Trainer", and also a piece I wrote for the Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. Both of these are enclosed for your perusal. The Gunnery Trainer did a good deal to advance the process for it gave us the opportunity not only to show the feasibility of the basic idea of taking and projecting wide angle pictures but also work out many of the smaller bugs which are bound to come up in any development of scope. I might add that at the time a great many people said that it was not possible to turn over a device requiring multiple projectors to inexperienced people and expect to get efficient performances. There were eighty-five trainers built and each one of them ran millions of feet of film. Often they ran schedules of as much as 15, 18 and even 24 hours a day...seven days a week. The operation of the equipment proved entirely practical, after a short period of training for the operators, which we conducted ourselves. I felt we had knocked down conclusively the doubters who said the equipment might be difficult to operate. At the war's end, an Air Force publication at Wrights Field gave the Waller Gunnery Trainer credit for saving over 350.000 casualties. |

|

The Vitarama Process for Still Pictures |

|

We finished work on the Gunnery Trainer in

December 1945. I was anxious to get back to work on the use of the process

for theatre use. Just as I started, I was called in by Time Inc., upon the

recommendation of the Eastman Kodak Company, to develop special equipment

for a show they wanted to build for promotion purposes for LIFE Magazine. We

worked out for them a set of projection equipment to show still pictures on

wide five-panel screens. Again, this was the use of the wide-angle

principle...but this time made portable so that their presentation should be

shown on a few hours notice. A presentation called "The New

America" ..meaning the new post war America.. was made by TIME, Inc. It proved

to be spectacular. It served their purpose well and was used all over the

country at business men's meetings, conventions, etc. Later the State

Department asked to borrow the equipment because they felt the presentation

would make fine propaganda for the United States. Time, Inc. agreed and in

1948 and 1949 the presentation was used in Germany with our portable

equipment. Another set was sent to Japan, at the request of the State

Department. Reports we received on showings in these countries, at opposite

ends of the Earth, were excellent. The show was ideal for propaganda purposes.

The State Department was pleased. We finished work on the Gunnery Trainer in

December 1945. I was anxious to get back to work on the use of the process

for theatre use. Just as I started, I was called in by Time Inc., upon the

recommendation of the Eastman Kodak Company, to develop special equipment

for a show they wanted to build for promotion purposes for LIFE Magazine. We

worked out for them a set of projection equipment to show still pictures on

wide five-panel screens. Again, this was the use of the wide-angle

principle...but this time made portable so that their presentation should be

shown on a few hours notice. A presentation called "The New

America" ..meaning the new post war America.. was made by TIME, Inc. It proved

to be spectacular. It served their purpose well and was used all over the

country at business men's meetings, conventions, etc. Later the State

Department asked to borrow the equipment because they felt the presentation

would make fine propaganda for the United States. Time, Inc. agreed and in

1948 and 1949 the presentation was used in Germany with our portable

equipment. Another set was sent to Japan, at the request of the State

Department. Reports we received on showings in these countries, at opposite

ends of the Earth, were excellent. The show was ideal for propaganda purposes.

The State Department was pleased. |

|

Cinerama Corporation Formed |

|

|

This interrupted hardly at all our work on the

picture process. Towards the end of 1946 it seemed time to set up a separate

corporation to concentrate work on the picture process. Cinerama Corporation

was formed in November. Mr. Rockefeller and Time, Inc., some of whose

executives had by that time become interested in various aspects of my work,

agreed to finance the building of certain minimum equipment for the

production and showing of pictures in the Cinerama process. They wanted me

to be able to demonstrate the effect of the process in sight and sound...to

show what it might do as a process for commercial entertainment. |

|

Further Screen Development |

|

|

There was still a good deal of development

work to do. A difficult problem was the adaptation of the spherical screen

to some form practical for theatre entertainment. The spherical screen was

satisfactory for the gunnery trainer. Each of the four men it would

accommodate was at, or close to, the center of the screen. But for a large

theatre audience this was not practical. It was apparent that vertical lines

would become distorted when viewed from seats at the side. Imagine the

effect of a mast of a boat, for example, viewed from the side of a spherical

screen. Our plans thus called for a cylindrical screen. Louvres then were

mounted in straight lines rather than arcs. The next consideration was

appropriate size. |

|

Size of screen |

|

|

For a fair-sized theatrical audience, we felt

it was necessary to have a screen triple the height and four times the width

of the normal screen. This meant a total area of twelve times. When images

are magnified too many times, however, the power to resolve or define such

images is lost. Therefore, more photographic area was required than was

available in the standard sized motion picture frame. Five such frames were

found necessary on the gunnery trainer but for theatrical use, it was

impractical. I conceived the idea of using a standard motion picture

projector but with a large frame. We arranged to pull down six perforations

per frame instead of four, thus providing a frame 1.12 inches high instead

of 0.75 inches high and, of course, one and one half times the area of the

standard frame. By using three of these frames to project the total image,

we would have four and half times the film area available; consequently,

four and a half time the definition. This still allowed the use of standard

motion picture film, so desirable because of its established manufacture,

processing, handling, etc. It also gave us a film frame that was more nearly

square than the standard oblong frame. As the diagonal of a square is

smaller in proportion to the area of the square than is the diagonal of the

oblong in relation to its area, we achieved an optical advantage; all

lenses, light beams, etc., being circular in cross section and a square fits

into a circle more efficiently than an oblong does. Having settled the size of the frame and the screen, we moved on to the building of the screen. We chose steel for our first louvres for ruggedness and to allow few supports; but this proved impractical. They reverberated to sound and put up a continual hum. Later we came to the use of strips of conventional screening material which we now use and find satisfactory. |

|

Match Lines |

|

|

With our first 16mm models - and in our 35mm

gunnery trainer - the joints between

the screen areas were simple, straight lines. They showed as sharp dark or

light joints. The best way to conceal these joints was to have the edges of

the images gradually fade out and overlap the fading edges so that you could not see just where one

started and the other ended. We experimented with and patented an optical

system and a photographic vignette printed on the film but both of these had

bad features. The ideal method was to have a lineal attenuation of the light

on each side. One morning I got the idea of taking advantage of the ability

of the human eye to integrate or average to total illumination of different

length light flashes so I designed our present device which we have given

the nickname "Jigalo" because it moves rapidly up and down. This is really a

light chopper made with saw tooth edges which move faster than the eye can

perceive. The end of the teeth give a very short dark period and a long

light one and gradually as you approach the base of the teeth the condition

is reversed; a very long dark period and a very short light one until

finally it is all dark. This patented method gives a truly lineal lessening

of light and when the two edges, one growing dark to the right and the other

to the left, are overlapped, the joint has practically disappeared. |

|

Final Sound Development |

|

|

Throughout the long years of development, my

concept was to give an audience an entirely new experience in a medium of

entertainment. I knew that this could not be achieved without a sound system

which would provide as much perspective and realism as did the pictures. We

had to have something far superior to anything developed to date. We experimented with the new magnetic sound medium and made tests with three sound channels, feeding three loudspeakers behind the screen. This was good but gave us gaps in the sound as sound sources moved across the screen, so we tried five channels. We found this system not only gave us uniform volume for sound sources moving across the screen but also greatly enhanced sound perspectives; i.e. difference in sound as it moves toward and away from the audience. We decided to take this up to six channels in order to have sound follow the action out beyond the screen limits. In working originally with this system, we assumed we would have to monitor or modify quality and volume on the individual channels manually. But as we worked with it, it became much simpler than that. We found that by setting the microphone in the same relationship to the scene being photographed as the speakers were to the scene when projected, we achieved a realistic quality far better than was possible before. No sound reaches the human ear entirely from a single point. A great deal of it is reflected from surrounding objects so that the ear receives sound from many source, each reflection having its own particular quality. This is also true of the multiple microphones and it is the combination of all these qualities that so well reproduces the sound and the changing sound perspective in the present Cinerama process. |

|

Basic Reasons for Realism of the Process |

|

|

Our modern researchers in physiological optics

and psychology have generally agreed that our interpretation of the image

our retina receives, which is sight, depends on our experience. Through this

experience we have developed a number of clues, our judgment of which gives

us the ability to place ourselves in space, to judge the distance to objects

in our surroundings, to know how fast we are moving and how other

objects are moving in relation to us. All of this is our reality. Some of the more important clues are - Atmospheric or color perspective, i.e. the gradual graying or blueing of objects which are further away. The known size of objects - Objects which we recognize and know the size of help us to judge their distance. Overlay - The fact that an object which is in front of another hides part of its image or overlays it. Relative brightness - usually objects closer to us are brighter than ones further away. Movement parallax - The use of this clue is one of our ways of checking our distance to objects. When we want to find out just where they are we usually unconsciously sway our bodies or heads slightly sideways and in this way cause the objects close to us to move more than the ones further away. Movement Perspective - When we are moving forward, as when walking, driving, etc., all the surrounding objects move in a definite pattern from a plain enlargement of those directly in front to a rapid movement of close objects on our side. This pattern, particularly in our edge, or peripheral, vision is one of our best clues to the speed of our movement and the distance to objects at various distances. All of these clues to spatial relationship - and many others that we use in sight and sound - are included in the Cinerama process. Therefore, Cinerama recreates reality. That is the story of the Cinerama development. There are still some things to be done by way of refinement but the basic work is done and the demonstration sequences made. During the last six months we have shown our demonstration to a few people to get reactions and suggestions. By and large, these have been most favorable. We are ready now for the production of our first picture and are negotiating with several groups to bring that about. Since the organization of the Cinerama Corporation the latter part of 1946 some $400.000 has been spent to further develop the process and make test shots. The ten years of experimentation and development by The Vitarama Corporation, including the experience gained by building, installing and running gunnery trainers, started Cinerama Corporation off with an extremely valuable asset. |

|

|

This letter is long. I have done my best to

condense the story of a twelve-year development. Needless to say, there are

dozens of aspects not touched upon here, any of which I'd be glad to go over

with you I appreciate your interest, Bill, and hope you'll call on me for anything else you need. An article written by you would certainly be a grand thing for us. Sincerely, Fred Waller - President dw PS I am enclosing mimeographed description of each piece of Cinerama equipment as it is today; also two pieces re. gunnery trainer. Would appreciate return of the latter as they are all that's left. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 05-01-25 |

|