This Cinerama Show |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Lowell Thomas, 1953 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

FAMOUS as a commentator of radio and screen, it was Lowell Thomas who

furnished the drive that resulted in the opening of "This is Cinerama" on

Broadway. As a world traveller and early producer of adventure-travel films

he saw in the Cinerama system possibilities of bringing to the people at

home the wonders of foreign lands and their interesting people. He is

president of Cinerama Productions. FAMOUS as a commentator of radio and screen, it was Lowell Thomas who

furnished the drive that resulted in the opening of "This is Cinerama" on

Broadway. As a world traveller and early producer of adventure-travel films

he saw in the Cinerama system possibilities of bringing to the people at

home the wonders of foreign lands and their interesting people. He is

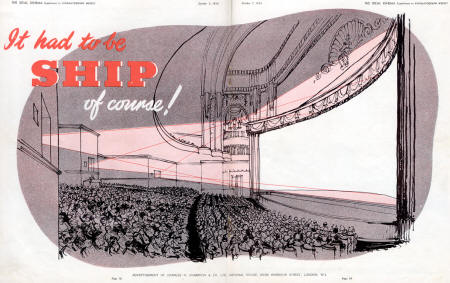

president of Cinerama Productions.FORMER PRESIDENT Herbert Hoover, while in the White House, as well as in recent years, has so often shown by his actions and his words, that he once was an engineer - one of the foremost engineers of our time. But never did he reveal it more graphically than in a recent comment he made concerning something revolutionary that has literally turned the entertainment world upside down. Said the ex-President: "I believe the Cinerama is the fifth great revolution in pictures: (1) Silent movies; (2) Talkies; (3) Color; (4) T.V.; (5) Cinerama." No superlative adjectives there. In fact no adjectives at all. Yet what more potent comment than that could be made? From coast to coast Cinerama has been the talk of the year. So far it has been presented in only three cities; New York, Detroit and Hollywood—with perhaps Chicago and one or two others by the time this appears in print. In spite of this, Cinerama is a subject of conversation in almost every city, town and village in North America. Mail requests for tickets have poured in not only from all over America but from foreign lands as well. One party radioed from far-off Singapore, asking for tickets on a certain date. The Russian delegation to the U.N., unable to get reservations when they wanted them, told their woes to the chief delegate from another country. He, wanting to show that he had more influence than the "Russkies," phoned Grover Whalen, modern "Father Knickerbocker," asking if he could pull off the miracle, just so this Ambassador could show to the gentlemen from Moscow that he had more "pull" than they. |

More

in 70mm reading: The Entire Development of the Cinerama Process mr. cinerama The Birth of an Idea Cinerama Goes to War Adding the Sound to Cinerama Finding Customers for a Product in70mm.com's Cinerama page |

|

The Cinerama premiere, of course, was in New York. Seven months later it

arrived in Hollywood. My colleagues and I were a little worried. We figured

that maybe Hollywood, still the film capital of the world, might resent such

a long postponement, and be annoyed because New York had the premiere of

this revolutionary cinema innovation. But, happily it didn't work out that

way. Dick Button, Olympic star, foremost skater of all time, wrote me as

follows: "The most frequent comment around us at the Hollywood premiere was:

'I expected another one of these 3-D things, but nothing as fantastic as

this. It really will change the movie industry.'" I had planned to be at the Hollywood opening but at the last moment was obliged to fly to New York. So my wife and I gave our tickets to a newly-wed couple—the bride, a widow who owns the farm next to us in New York State's Lower Berkshires. She reported that one of my old friends, Charles Skouras, sat behind them, and kept saying over and over: "This is the best of them all! Why bother about the others?" The Los Angeles Times gave the long-delayed Hollywood presentation nearly a full page in the news section, under the following heading: CINERAMA GIVES FILMS NEW THRILLS – SHOW OF SHOWS OUTDOES ALL IN DAZZLE, EXCITEMENT, MAGNITUDE. Jimmy Starr, in his review in the Los Angeles Evening Express, summed it up thus:— "Movieland's revolutionary new medium - Cinerama - brought old-time Hollywood glamour back to the boulevard last night ... it was Glitterville's most exciting night since the late Sid Grauman opened the Chinese Theatre." Just what is Cinerama? How did it happen to happen? How many years have been spent developing it? Why did the Rockefeller and Time and Life people step out? And how did it finally emerge from the laboratory? These are some of the questions that are put to me almost daily as I move around the country.  No doubt you have noticed how some of the major events of your life come

about through pure chance, an item that you see in a paper, a fragment of an

overheard conversation, turning down one street instead of another, an

accidental meeting with a friend, and so on. Well, that's the way it was

with this. No doubt you have noticed how some of the major events of your life come

about through pure chance, an item that you see in a paper, a fragment of an

overheard conversation, turning down one street instead of another, an

accidental meeting with a friend, and so on. Well, that's the way it was

with this.It all began one afternoon about four years ago. I had been recording a picture at Reeves Soundcraft Studios on East 44th Street in New York. Now, I had known "Buzz" Reeves some twenty-odd years before, in the days when we little dreamed that he would become a top tycoon in his field. I had just gotten under way in radio, stepping into the spot where Floyd Gibbons had made a name for himself. This was right before I began a seventeen-year association with Twentieth Century-Fox, and at the time I was working on miscellaneous shorts for Paramount and other studios. "Buzz" happened to be the engineer who handled some of my recording. After that I saw nothing of him. But I did hear how he had soared to the heights as head of various technical firms. Wondering about my old friend, who had become a legendary figure, I asked about his office and found it was right there in the building where I had just finished recording. So I dropped in and we chatted about the old days, and about the bewildering world of electronics. Among other enterprises, he mentioned he had recently bought an interest in something new and revolutionary. He told me how the heads of the Time and Life organization and one of the Rockefellers had become discouraged and sold their interest to him. He told me it had to do with something invented by Fred Waller. This increased my curiosity, because when "Buzz" and I had worked together long years before, Waller was the engineering genius and trouble shooter for Paramount. I had also worked with him. And so it was that "Buzz" lured me to Oyster Bay. There from both Reeves and Waller I heard the story of Cinerama, how its origin went back some fourteen or fifteen years to the New York World's Fair, how the Government took it over during World War II and backed Waller in the development of a special Gunnery Trainer, using a circular screen that went all the way around a big room with one continuous motion picture projected by eleven machines. Then they told me how, after the war, further experiments were made possible by Rockefeller and Time and Life money. But neither the inventor nor his backers thought they had it ready for the public. It was at a moment when enthusiasm was at a low ebb that "Buzz" Reeves had arrived on the scene, bought out the other backers, and added stereophonic sound. Then, in their Oyster Bay indoor tennis court which they used as a laboratory, they showed me some of their test shots. When I saw these I was literally overwhelmed. I don't know, but perhaps my special background and past experience played an important part in getting it out of the laboratory. During World War I, assisted by a number of great cameramen—Harry A. Chase in particular - I had made what up to that time had been the most successful non-fiction film production ever presented. It was called "With Lawrence In Arabia - Allenby In Palestine." Actually it was a combination of two pictures, dramatic records of two World War I campaigns which were so closely related that I had condensed them into one show. This "Allenby-Lawrence" production had broken all records in London, and then for years I had toured around the world with it. Following that I had made a similar film production called "Romantic India," which was full of the glamour and adventure of the most picturesque country on earth. So when I saw Fred Waller's Cinerama and heard "Buzz" Reeves' stereophonic sound, I thought to myself what a fantastic thing it would have been if I could have used that medium for telling the story of the exploits of Lawrence of Arabia and of Allenby's cavalry army sweeping through Palestine to Jerusalem and Armageddon! For Cinerama brings you the world of reality in a way beyond our wildest dreams. In the forty years that I have been associated with the entertainment world I have never encountered tributes comparable to those that have been pouring in since that historic New York opening night. Enthusiastic comments — all unsolicited — have come from far and wide, from people in all walks of life. How did we happen to build our first show in the way we did, the production called, "This Is Cinerama?" Because of what it does to real life my first thought was to call in an old friend who has often been referred to as "the father of the documentary,"—Robert L. Flaherty. Bob Flaherty, of course, is world-famous for his "Nanook," "Moana," "Man of Aran," ''Elephant Boy," and others. I invited Bob out to Oyster Bay to look at the tests. To say he was excited would be an understatement. For a month or so, Flaherty tested the camera and studied the new medium. And then, alas, just as he was to set forth round-the-world, Bob Flaherty died. For the moment there was no one to take his place. So, in the hope that I at least might set our organization in motion I rushed over to Europe and began looking for subjects suitable for a series of demonstration episodes. Harry Squires and his crew followed, with Michael Todd, Broadway producer, assisted by his son, filling in for Flaherty. As their material began pouring in there was the problem of cutting and editing. From television we lured Bob Bendick to help on this. Also, we brought in one of the top figures of the motion picture world - Merian C. Cooper. Like Flaherty (and myself) "Coop" had begun making documentaries back in the silent days when, in association with Ernest Schoedsack, he had made such classics as "Grass" and "Chang," followed by several hundred successes from "King Kong" on down to "Fort Apache" and the recent Academy Award winner, "The Quiet Man." "Coop's" capacity for hard work is prodigious. For months during the production of the film he would fly back and forth between the east and west coasts, often several times a week, to keep up his rigorous schedules in both New York and Hollywood. Day after day he would work right around the clock, exhausting his crews. But our production was beginning to take shape. With Bendick he cut and edited the European material, then together they went down to Florida to shoot the Cypress Gardens sequence. Our "America The Beautiful" was conceived by several of us. Years before. Cooper, a World War I aviator, had hedge-hopped his own plane through the jagged canyon country of our national parks. Wanting a spectacular finale he came up with the idea of a plane flying across the entire United States from east to west. For this he called in our top stunt pilot and three-times winner of the Bendix Trophy, Paul Mantz. He worked out, with Mantz, an itinerary for the jaunt, and virtually directed the film by long-distance telephone calls to Mantz, to cameraman Harry Squires and to Fred Rickey, the director-on-the-spot. Of course this hodegpodge of film needed the final touches that make all the difference between a mere demonstration and real showmanship. Cooper supplied them. He brought in artist Mario Larrinaga, with whom he had worked on "King Kong" and other films, to prepare the transitions that introduce each episode in "This Is Cinerama." Also, he selected veteran composer-conductor Louis Forbes - of "Gone With The Wind" fame - to handle our complicated music problem. Scoring a film involves intricate timing, cues, following the action on the screen, and adjustments in the music right during recording sessions. For an ordinary picture, this is difficult enough. But the Cinerama screen is almost six times the size of the average theatre screen. In addition, to take full advantage of "Buzz" Reeves' high fidelity, multi-directional sound, a whole battery of microphones had been set up, each channeling into a separate sound recorder. Forbes had to keep all of this in mind while composing, orchestrating and conducting his music! Some measure of his success is to be found in the reactions of the audiences at the Cinerama presentations. They never fail to mention the unprecedented realism of the orchestral sound. Even more impressive is an incident that took place at the conclusion of the first recording session. Forbes asked Dick Pietschmann to run a playback of the performance, for his musicians, and the men - all drawn from the NBC Symphony, the Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra—listened with rapt attention, then burst into applause. "Never before have I been able to hear myself exactly the way everyone else hears me," was the way one violinist summed up the reaction. And then I had a special personal thrill. It was decided that we ought to have an introduction to "This Is Cinerama," tracing the development of motion pictures and leading into our new dimension, plus an introduction to the second half of the film to be shot on the Cinerama camera. A reproduction of my library was set up in my rural radio-TV studio on my farm near Pawling, N. Y. And thus I became the first actor to appear in Cinerama—with my barn-studio the first real Cinerama studio. Meanwhile the opening date was drawing near. We had contracted for the Broadway Theatre and announced our premiere for September 30, 1952. As is customary in the business, we invited critics from the national magazines out to Oyster Bay to look at our picture in advance of the opening. But, with less than two weeks to go, we could still show them only parts of the production—and not all of that with the music track on it. "Coop" was literally still working on the picture up to an hour or so before the Broadway opened its doors. And what a night that was! Another custom of the industry is to invite celebrities in town—the movie and stage stars, the executives and local politicos—to attend your premiere, to fill your house with glamour. Veteran MGM producer Louis B. Mayer, who became chairman of the board of Cinerama Productions a few weeks after the opening, vetoed the idea. "Why bother?" he said. "They'll all phone us tomorrow!" The phones are still ringing, but even so we had a premiere that made Broadway history. The audience could have been an entire chapter out of "Who's Who In America." It included an ex-President, Governors of several states, leaders in industry and society, stars, composers, playwrights and authors, and so on. A night that was a fitting climax to the years of effort that went into the development of Cinerama, a gratifying reward to Waller, Reeves and many of us, for the time and patience and skill that had gone into the creation of the first Cinerama production. It also was a night to remember for Frank Smith, Dudley Roberts and their associates who, along with me, had organized and financed the company now known as Cinerama Productions. At last we have removed pictures from the age-old limitation of space—the picture frame. From the earliest days all scenes, in pictorial form, have come to us in a concentrated space: square, oblong, or what-not. You were always conscious that it was surrounded by something else: a book, a wall, the setting of a room, the darkness of a theatre. Always it was something that would not fill your vision. But in this newest development you are confronted by a picture so vast, so all-enveloping, that you see nothing else. Your eyes no longer are aware of any limitation. There is no frame. You are right in the middle of it, and that is the main point about Fred Waller's historic invention, together with "Buzz" Reeves' flood of stereophonic sound. Fred Waller calls it "peripheral vision." That is, you not only see what is straight ahead, but you also see out of corners of your eyes—just as you do in real life. In life much of the vividness is produced by the side glimpses — the things passing by. That's the most dynamic part of vision. The principal of "peripheral vision" produces an extraordinary illusion—makes it seem more vivid even than reality, because you witness a daytime scene when the theatre is actually dark. So there is no diffusion of daylight in the atmosphere, and that makes the color all the more spectacular. The scene seems to engulf you. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I hadn't stopped in to see "Buzz" Reeves that afternoon several years ago. We would probably have had Cinerama someday. Reeves would have seen to that. But, it might not have come for a few more years. At any rate I would have missed one of the greatest adventures of my life. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 05-01-25 |

|