Finding

Customers for a Product

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Lynn Farnol, 1953 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

Mr Lynn Farnol Mr Lynn FarnolIN this day when most publicists like to be called "public relations experts" Lynn Farnol continues to call himself simply a publicist. Whatever the name, he has been known for many years as one of the most skilful of the many who have worked in the entertainment fields. For many years he was associated with Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Since 1950 he has had his own organization. His promotion of Cinerama is an example of what a publicist can accomplish in attracting public attention. THE INTRODUCTION of a new product (and that includes entertainment) involves some questions: Is the public ready for it? Does it fulfil a need? Since the scrapping of old goods or processes may be involved, are the new elements important enough to compensate for the loss? The sponsors of Cinerama believed in Cinerama. They had faith that it presented a new sensation in entertainment. They believed that it was a new way of telling stories, without the old frame of the traditional motion picture. Much money and much time were staked in that conviction. A policy was established, as clear cut and as well defined as any ever known in or out of the motion picture industry. Without making any secrets out of anything, the technical details of the operation of the new process were not to be divulged. |

More

in 70mm reading: The Entire Development of the Cinerama Process mr. cinerama The Birth of an Idea Cinerama Goes to War Adding the Sound to Cinerama This Cinerama Show in70mm.com's Cinerama page |

|

Interest was to be deflected from the mechanical details. Equally urgent was

the policy that interest was to be deflected away from the specifics of the

entertainment that was to be offered. Lastly, Cinerama was to state,

bluntly and directly, that it was not a three-dimensional process. Thus, by a process of elimination, most of the standard appeals were taken away from the advertising and from the publicity operation. The appeal adopted by the advertising agency, McCann-Erickson, and its able account executive, Peter Schaeffer, and the company's publicity representatives was a simple one: what Cinerama does to you! It meant, during the pre-opening days, taking one editor after another to Oyster Bay to see the laboratory tests. The trip was a long one. Three hours might be spent waiting to see a five-minute segment of the film. One or two partial laboratory previews were held. The belief spread that, mechanically, Cinerama worked and, emotionally, it produced an extraordinary effect. Publications, with their two dimensions, began to improvise and plan ways of presenting Cinerama with its illusion of a third dimension. A facetious editor suggested that it could easily be solved by publishing a curved magazine. By the time opening night came - without the benefit of any formal preview, and without anyone having seen the whole of the film - a healthy excitement and anticipation had been built up. There was a sense that new demands were going to be made on the audience. An audience was conditioned to become a part of the picture. The basic premise of the opening night was to depart from the usual and the conventional pattern of motion picture openings. The audience was a distinguished one, comprised of many leaders from the business world, friends of the sponsors, and many leaders of the publication and radio world, friends of Lowell Thomas. But what made the event unique was that the opening night press guests included outstanding music writers, travel editors, science authorities - in fact, leaders in every field touched by Cinerama as a medium. It was an opening planned not for New York, nor for New Yorkers, but for national penetration. It worked, in that the New York Times did carry the story of the introduction of the new process on the front page, and all of the wire services carried it not only once, but two or three times. Many national radio and TV commentators of the caliber of Arthur Godfrey and Edward Murrow raved about it for weeks after. Within three or four days after the opening, every city and every town in America had read or heard about the film revolution. Not only that, but once the first story appeared, it seemed to create an appetite and a demand for more news and more information. Thousands of clippings began to pour in from every corner of the country, and from the distant capitals of the world. A carefully kept file of the 183 potential markets for Cinerama was prepared. For each city in which Cinerama may play, a complete collection of everything that has been in print in that area is available. The measure of public interest and information is immediately and accurately available. |

|

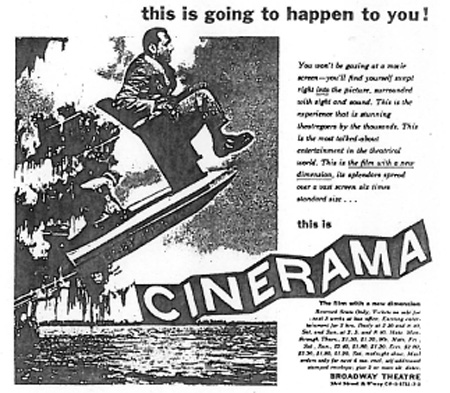

A NEW dimension thrill was stressed in all Cinerama advertising. Emphasis

was placed on what was going to happen to the spectator. Here Peter

Schaeffer, McCann-Erickson account executive, served as his own advertising

model. A NEW dimension thrill was stressed in all Cinerama advertising. Emphasis

was placed on what was going to happen to the spectator. Here Peter

Schaeffer, McCann-Erickson account executive, served as his own advertising

model.Once the opening was accomplished and the story of Cinerama carried across the country and around the world, the next problem became one of building up an operational plan and an acceptance of mail order sale for tickets. It is a practice used in a limited way in the legitimate theatre, and not at all in motion pictures. McCann-Erickson used coupon advertising and radio spots to invite orders by mail. Publicity announcements and feature stories stressing the ease and convenience of buying tickets by mail became increasingly effective as tricks of the trade were learned. Once the New York operational procedure became established, it became fairly easy to adapt publicity and advertising techniques to Detroit, Los Angeles, Chicago and other key cities. The effort and the pattern continued to be the same. Make an event out of the opening. Stress the emotional excitement that is in the film. Avoid a program of parts for the entertainment, and leave the technical details alone. Because mail orders are the very basis of a successful operation, stress the fact that Cinerama will not be shown in neighborhood houses, and carry the announcement of opening and the ticket sale to the widest possible area, so that an extended circle, including as many as 20 surrounding cities, might be included. As an operation of merchandising entertainment, it was sound and it is sound. Cinerama was launched with a label that was scrupulously honest and fair to the public. It was presented as a process that might satisfy a great need and hunger of the public for something new. The public provided its own answer. They got what they wanted. In precipitating the revolution in entertainment that it has, much of what the industry regards as its most valued properties may be made worthless, but something was accomplished, too - audiences came back to theatres. And now what? How long the technical mechanical problems will continue is anyone's guess. It is a reasonable supposition that in due time, they will be evaluated in terms of cost of installation, in terms of operating costs, in terms of what they give an audience as a process. Then the question will be not which of the processes do we prefer, nor how good are films that convey a third dimension or the illusion of a third dimension, but instead, another and more important question: What is the industry doing with its new dimension? What stories are they telling better, now that they have this new dimension? In other words, what have we to say in Cinerama or any other process? |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 05-01-25 |

|