"A Year Along the Abandoned Road"

|

This article first appeared in |

| Written by: Morten Skallerud | Issue 65 - July 2001 |

|

|

Further in 70mm reading: |

A Magical, Deserted Place |

|

70mm

frame supplied by Camera Magica, Norway 70mm

frame supplied by Camera Magica, NorwayThe story of the film starts with the place it portrays: Børfjord, a semi-abandoned village, the personality of which contained its own filmic language. I came there for the first time on a location scout for another film in January 1980, and immediately loved the place. It had all this "Arctic magic" -- the midnight sun during summer, two months without any sun at all during winter, and the Northern lights. It had steep mountains close to the sea, and such a variety of vegetation. The whole natural setting was magnificent, telling man how small he is in nature's own context. Also, the houses and the overgrown road said a lot about people living in the middle of harsh nature. Some 60-70 people used to live here. Most of their houses lay on the east side of the fjord, down near the sea, and close to the internal village road. They supported themselves mainly with fishing, and some had small farms. Now nobody lives there. In winter, several months may pass without a single person coming near the place. The houses stay cold and alone with virgin snow between them. Only during summer do people come back to stay for their holidays, and Børfjord comes to life again for a short period. In October 1980, I walked alone on skis through this long-deserted village. It was a powerful experience. Passing all the vacant houses and barns, boat houses and piers -- and being the first person to make tracks across the snow -- gave me such an overwhelming feeling of abandonment. The virgin snow more or less became the symbol of a village left alone. I discussed this with Aslak Mienna, a local reindeer owner who later became a central member of our shooting team. He said, "Can't you recreate this in your film?" And this is more or less what we did. |

|

The Place Decides the Language |

|

|

Having worked quite a bit with "strange" ways of making film, I soon started playing with the idea of using animation techniques to bring out some of Børfjord's latent magic on film. But I also wanted it to be a true film -- at least as true as an ordinary documentary film would have been. Then suddenly came the main idea: to combine a one-year time-lapse with a continuous tracking shot through the whole village. By shooting one frame at a time, and moving the camera forward between each frame, the result would be some kind of a "magic journey" through both time and space. It could make a true portrait of

Børfjord: we would see the whole village, and at the same time experience the place's contrasts and yearly cycles of nature and population. In the winter part, our audience would feel much like I did moving across virgin snow between cold and abandoned houses. |

|

Lifting the Time Perspective |

|

|

We would lift the time perspective far above our normal human vision. Seasonal changes (snow melting and snowfall, vegetation changes and so forth) should be seen in a tempo that we could follow. The "smaller movements" -- like weather changes, flood and ebb and, for that matter, people and "other animals" -- would become less important. Doing it this way would mean that grand nature itself had to play the main role. But this is also a true perspective -- especially in a place like this. Lifting the time perspective would reveal a lot about the relationship between man and nature. |

|

People in Time-lapse |

|

|

What about filming people in a time-lapse film? In this large time perspective, people inevitably will seem small, rapid, inconstant and incalculable, like insects as seen with "normal" human eyes. Generally, this should be avoided. However, in our context this "insect effect" worked fine. All the sections with people in them were staged carefully, partly involving a pixellation technique as well. We wanted the people to seem rapid and incalculable, but at the same time, we wanted them to come close enough for an audience to care about them. They are men and women of all ages. Genuine and proud people, many of them are marked by a life of toil in a tough climate. Instead of saying, "Look how small people really are," the images should say, "Look how large nature is compared to man!" Since we do care about the people, the changes in nature become even more mighty to us. |

|

A Day and a Year |

|

Working

with the camera train at night. Photo by Knut Skoglund / Camera Magica,

Norway Working

with the camera train at night. Photo by Knut Skoglund / Camera Magica,

Norway Another basic choice we made was to "tie together" the one-year cycle and the day-and-night cycle (spring = morning, summer = day, autumn = evening, winter = night). This is actually not far from the truth about Arctic seasons, with the sun up 24 hours a day during summer, and no sun at all during the winter. Ideally, we always should have been shooting in Børfjord when the seasonal changes actually happened (snow melting, ground turning green, autumn colors coming, snow falling), while in the more "static" periods, we could wait. However, in Finnmark, these changes are unpredictable. For instance, the snow-melting period may vary two to three months from one year to the next. We had to guess. Thanks to our local connections, we often guessed right. |

|

Moving in Time-lapse |

|

|

Outdoor time-lapse scenes often seem flickering and unpleasant to look at because of all the weather changes. We had a theory that a smooth camera movement would "outweigh" all these small disturbances. So we shot a primitive test film back in 1982 to see if this theory was right. It was; even large changes that would otherwise seem ugly turned out nice and smooth with the camera moving. Another great thing about moving this way was the added involvement of the cinema audience -- a bit like fun-fair cinemas where people stand up watching film scenes from helicopters and roller coasters on a half-dome. The audience of our film is also brought to feel that they are moving themselves -- sometimes nice and slow, other times a little too fast around the curves. (This effect is completely lost when the film is watched on a small TV screen.) |

|

Language Decides the Technique |

|

|

The whole Børfjord film was shot one frame at a time, moving on rails, leveling and adjusting tilt and pan for each frame. Since this kind of single-frame camera movement had never been done before (at least not that I knew about), we had to construct a system ourselves. The only thing we had that was "standard" was the camera itself. It was an old 65mm Super Panavision rack-over camera which was just perfect together with an animation motor that Frode Wik of

Wakemanfilm, Norway, had built for my 35mm Mitchell a couple of years before. We developed a system of flexible rails, and a heated "rolling house" for the camera (a "camera train"). A number of rail lengths could be laid out in front of the "camera train," adjusted to follow any horizontal or vertical curves. As we moved forward, we could take down the lengths we had passed and put them up in front again. We made four lengths of two meters and a "short length" of 1.5 meter. Each rail length has a round rail on one side (the steering side) and a flat rail on the other (the drive side). The flexible rails themselves are full of plastic and

aluminum. In addition, we made a solid steel base for each length. |

|

The "Camera Train" |

|

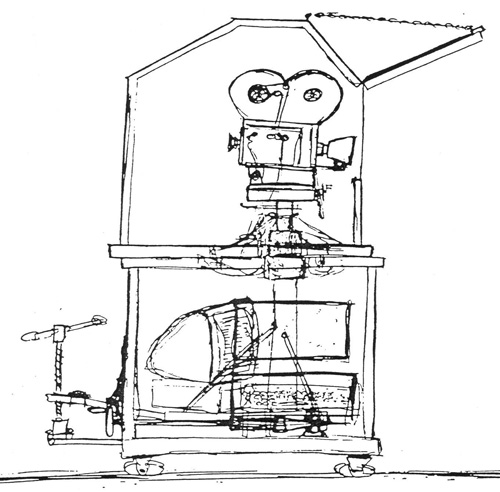

Camera

train. Drawing supplied by Camera Magica, Norway Camera

train. Drawing supplied by Camera Magica, NorwayOur "camera train" rested on six wheels: four inclined wheels ran on the round rail and did the steering, while a motor and an optical encoder were connected to each of the two wheels on the "drive side." A computer steered the motor, so that after each frame, the "camera train" moved forward to the next shooting position. We divided the housing horizontally into two sections: an upper house and a lower house. Between them, we made a flexible opening, through, which the column of the Crass animation stand could pass. The upper house might be turned in any direction on top of the lower house. Inside the lower house, we had the base of the animation stand with a leveling system connected to two leveling wheels on the outside. The computer was also placed inside, and so were the steering electronics as well as a light and an electric oven. The computer could be operated through a small trapdoor, which also provided an excellent opportunity to warm our hands! The upper house contained the 65mm camera mounted on a Crass animation geared head, a surveying instrument to help the panning, and the camera control and exposure unit. We made two large trapdoors: a front door to film through and a side door for operation. All electrical apparatus were run on 220 volt AC, which we got partly from a generator and partly from the local electricity network. We spent a lot of time laying out cables. |

|

Exactness and the Computer |

|

Camera

rails. Photo by Morten Skallerud / Camera Magica, Norway Camera

rails. Photo by Morten Skallerud / Camera Magica, Norway The whole film had to be shot in continuity as one single take, with almost no chance to go back and reshoot. Safety was very important. Forward movement along the rails had to be organic and accurate, changing speed as often as if we had driven a car. The computer helped us with this. It would calculate acceleration data for us each time we needed to change speed, and find shooting positions for each individual frame. Then, for each frame we had exposed, it would steer the "camera train" up to the next shooting position. However, tilt and pan could be adjusted frame by frame manually, following care-fully calculated schemes. We defined an accuracy of 1/100 of a degree in tilt, pan and roll, which we knew was more than good enough. Exactness in all camera moves was of major importance, since any jerking and instability would take the audience's attention away from the film itself. The technique had to be perfect in order not to be seen. |

|

Shooting and Finishing |

|

70mm

work print frame: Camera team with slate. Left to right Morten, Aslak, Knut

and Svein. 70mm

work print frame: Camera team with slate. Left to right Morten, Aslak, Knut

and Svein."A Year Along the Abandoned Road" was shot entirely with single-frame technique. Some of the time we worked with fixed time-lapse intervals, like when we had one 24-hour and one 30-hour session in May in the light of the Arctic summer sun, which circles 360 degrees around the horizon without setting. We also did some fixed-interval filming at the end of the film, which was shot at night in winter with the moon as the only light source. Each frame was shot with long exposure time, which is one of the great possibilities of time-lapse filming. Most of the time, though, we just laid out the rails and exposed our frames "as fast as possible" (which was indeed not very fast!). We made an average of 115 frames and a tracking distance of 36 meters (117 feet) per "moving workday" -- more in summer and good weather, much less in winter with bad weather. In addition to myself, the main shooting crew consisted of four people: Frode Wik and Sklak Mienna, plus Svein Anderson and Knut Skoglund, who are both active film workers in northern Norway. When moving, we always used three or four people at a time, while the parts with just tilt and pan could be done by one person alone. A total of 105 shooting days were spent. If we add all the "can't shoot because of bad weather" days, preparation days, traveling days, etc., we spent a total of 180 workdays (half the days of the year) in Finnmark during shooting. In addition there was all the administration and pre- and post-production work. Thanks to labor credits and private loans, we managed to finish the shoot in January 1989. It took another two years to raise the money we needed to finish the film. Completing the film went a lot easier, involving some of the best people available, including Jan Garbarek, Norway's famous jazz musician and composer, who wrote a great score for the film, and Jan Lindvik, who among numerous films had done the sound for "The Pathfinder" a couple of years before. Norsk Filmstudio in Oslo did the Dolby Stereo mix, while the six-track mix for 70mm was done at Pinewood Studios, England. Laboratory post-production was taken care of by Technicolor in London. "A Year Along the Abandoned Road" was shot with a 50mm lens. The film stock was 65mm Eastman Kodak 5247, except for the night part, which was shot on 5297. |

|

15 years later and the Soundtrack |

|

The

title track Jan Garbarek's "Twelve Moons" CD is the music for "A Year along

the Abandoned Road". The

title track Jan Garbarek's "Twelve Moons" CD is the music for "A Year along

the Abandoned Road".A Year along the Abandoned Road" had its premiere at the Grimstad short film festival in June 1991. Since then it has been to around 100 festivals and won 12 different prizes. 35mm prints are still being sent to festivals, and also distributed for pre-show screenings in Norway, Germany and France. A 70mm print is being screened at the 70mm film festival in Oslo each year in August. In 2002, the film was elected "Best Norwegian short film ever made" in a ballot organized by the Norwegian film magazine Rush Print. And the pop group A-ha used it as a basic for their music video "Lifelines". New 70mm prints were made in 2003 by the Gulliver laboratory in Paris, as a restoration project by the Norwegian Film Institute. The sound track for these prints is DTS digital. Jan Garbarek's music for "A Year along the Abandoned Road" forms the title track of his CD "Twelve Moons" (ECM records 1993). |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 21-01-24 |

Morten

Skallerud and his camera train during filming of "A Year Along the Abandoned

Road", May 1988. Photo by Knut Skoglund / Camera Magica, Norway

Morten

Skallerud and his camera train during filming of "A Year Along the Abandoned

Road", May 1988. Photo by Knut Skoglund / Camera Magica, Norway