CinemaScope 55 |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Christian Appelt. English translation by Dr. Alexander Reynolds | Date: 08.10.2007 |

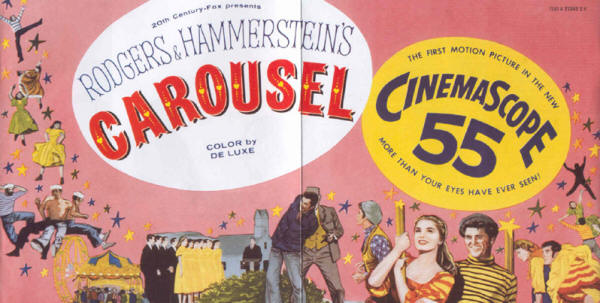

Poster

from Belgium. Hauerslev collection. Poster

from Belgium. Hauerslev collection. In the history of cinema technology we see a large number of processes, formats and technical inventions which were applied just once, or at best a few times, before dropping entirely out of use. Sometimes the reason was that a particular procedure did not prove as viable in the actual practice of film production or projection as it had been expected it would; sometimes it simply proved too costly; and sometimes its obsolescence was the result of a policy decision by the film companies. With hindsight, CinemaScope 55 appears initially to be no more than a curious footnote in the history of widescreen cinema. The technicians at 20th Century Fox developed their own film format (55.625 mm wide-format film) which also differed from other formats in the perforation pulldown foreseen both for filming and projection. There were, however, in the end just two films shot in this format: "Carousel" and THE KING AND I. After that, CinemaScope 55 cameras, lenses and copying apparatuses were all put in mothballs. In order to understand the logic behind CinemaScope 55, it helps to take a closer look at the circumstances of the introduction of CinemaScope by 20th Century Fox in 1953. Once the decision had been made to adopt a new widescreen process as the basis of the studio’s film production , the Research Department, under Earl I. Sponable, put together, in record time, a package proposal which combined long-familiar processes (film-recording by the anamorphic method) with the very latest technology (soundtrack recording and reproduction by the multi-channel COMMAG method, and the “ECN”, or Eastman Color Negative process). This package, however, had still to be presented in a manner appealing to the tastes and inclinations of the conservatively-minded film industry, notorious for its reluctance to invest in new technologies and methodologies. It had, indeed, really to be “sold”, in the most literal sense of this term, to the decision-makers in this industry. In his book WIDESCREEN CINEMA (1992) Prof. John Belton has brilliantly recounted this whole fascinating story of the development and the “selling“ of the CinemaScope format, with reference also to numerous original documents of the period. At the end of the 40’s, the studios were obliged by law to give up their studio-owned cinema chains, which had up until this point served as reliable performance outlets for every film produced by each of the majors. The arrival of television was already at this time causing a noticeable drop in box-office takings, while other sociological factors characteristic of post-war society (greater personal mobility, new housing construction, „commuting“ as a new work- and lifestyle) were also having perceptible negative effects on the film industry. The year 1951 saw the first successes of the new Cinerama process, with cinemas reconstructed especially to show Cinerama productions and films in this format, devoted to great journeys and current sensations, filmed outside of the major studios. Shortly afterward came the wave of “3D” productions, bringing it with design problems on the production side and even greater technical problems for the cinemas presenting the films once produced. The “3D“ craze proved indeed to be just that: a craze that came and went in a few short years. It served to stimulate, however, the development of the various widescreen processes. There was something of an over-hasty “cobbling together” about the formulation and introduction of the CinemaScope format. Time was of the essence. 20th Century Fox had, within a very short space of time, to get production in the new format underway and also to persuade the largest possible number of cinemas to re-equip themselves with new screens, new projection apparatuses and the new, more expensive multi-channel COMMAG sound facilities. Widescreen formats were, indeed, nothing new for Earl Sponable and his Research Department. He had already developed, at the end of the 1920’s, the “Fox Grandeur“ format, with its 70mm-wide film, which unfortunately soon fell victim to the general cost-cutting accompanying the rise of the sound film. Sponable had continued for years to press for the introduction of a 50mm format in order to improve picture quality. But it took the emergence of the real threats posed by Cinerama, 3D, and television to prompt the studio finally to take the risky step of introducing decisive alterations in the manner of recording and projecting film. Earlier attempts to persuade the film industry to switch to widescreen formats had met with no success. Researchers and developers of new production methods were bound to the 35mm format, such special installations as Cinerama were excluded. There thus arose the idea of recording film with an anamorphic lens: the only way that presented itself of accommodating a film-format of broader aspect-ratio within the standard 4-perforation frame with which cinematographers were being forced to work. The original composite-magnetic-print format used in CinemaScope to record both sound and image uses the whole available surface of the frame; the inner of the 4 COMMAG tracks could be accommodated on two narrow strips inside the rows of perforations. It was clear from the start that it was going to be difficult to make even this expanded version of the 35mm format yield images of an acceptable quality, since the bottom line was that there was now twice as much screen to fill as before. Larger screens and light-consuming anamorphic projection lenses caused a significant loss of light; attempts were made to compensate for this by the originally standard “Miracle Mirror“ screen and by thicker housings for the carbon arc lamps (the xenon lamp was introduced, indeed, as early as 1954, but came into general use only much later). Unfortunately, anamorphic projection not only restored the image compressed during filming to its original proportions but also magnified by a factor of two all scratches, dust-spots and other defects present on the film, as well as any slight lateral deviations from perfect stability in the projecting apparatus itself. Technicolor also needed some time to improve their colour printing process to such a point that even CinemaScope copies in Technicolor displayed an acceptable sharpness of image. In short, then, there was no overlooking the fact that – for all the enthusiasm inspired by the wide image and the stereophonic sound - CinemaScope had to contend, during the first months and years, with a large number of problems. In order to improve the quality of CinemaScope projections, Sponable proposed a measure which certainly owed something to the influence of the VistaVision process adopted as its own by Paramount. It had emerged in practice that the process of filming with wide-format film and then subsequently reducing it to the standard 35mm format displayed considerable improvements vis-à-vis the process of filming directly in 35mm. VistaVision film prints looked excellent even in 1:1.85 format, because the grain of the camera negative was, in the reduction process, also reduced, so that the superior sharpness of image largely preserved. It was also possible to produce large-format “special-performance prints “ for especially large-scale projections, so as to bring still more clarity and sharpness onto the screen. The task facing Sponable, then, was that of finding a moving-image recording process that would be, as far as projection and performance were concerned, compatible with the already successfully introduced 35mm Scope, so that the only new technology required would be for the actual filming. This new process should, in addition, also provide the possibility of the preparation of especially large-image copies for roadshow presentations. The result of Sponable’s efforts here was originally announced as “CinemaScope 4x“, later, however, acquired the appellation “CinemaScope 55“. For the actual filming process there was used a converted 70mm camera which Sponable had had built already in 1930, by Mitchell, for the old “Fox Grandeur” format, with its 4-perf pulldown as opposed to the standard widescreen 5-perf. This camera is still on display today in the museum of the American Society of Cinematographers in Los Angeles. The film gate on this camera was four times as big, almost to the millimetre, as the image recorded on the film of a CS projection copy. For actual filming, there were used “Super CinemaScope” special versions of the second generation of anamorphic taking lenses manufactured especially by Bausch & Lomb. Initially, the 55.625mm-wide Eastmancolor raw film stock had to be cut, perforated and processed by Fox themselves; only later did Kodak begin to deliver the stock ready-made for filming. This „XXL-Scope“ was then reduced by an optical printing process to 35mm format, a procedure intended to result in a particularly sharp and fine-grained image. As at the time of the introduction of the original version of CinemaScope, the test filmings were shown in demonstration performances which, it was hoped, would convince cinema proprietors and technicians of the advantages of the new format.  And the reaction of cinema proprietors was indeed – so far, at least, as

an accurate account of it has come down to us – enthusiastic. They were

particularly pleased at the fact that no re-equipping of their cinemas,

or new investment vis-à-vis the older version of CinemaScope, would here

be necessary. The elaborate promises made in the accompanying publicity

– „scenes recorded perfectly, with no distortion“; „a perfect view from

every seat in the house“; „brighter colours; clarity right through to

the back of the picture“ – should, of course, be taken with a pinch of

salt, since the very same promises had been made, in almost the very

same language, at the time of the demonstration performances of 35mm

CinemaScope. One noticeable difference, indeed, was the dropping of the

former emphasis on the three-dimensional qualities of the CS

screen-image („The Modern Miracle! You Can See It Without Glasses“).

Such emphasis was now superfluous, the great competitor in this respect

– 3D – being no longer a factor in the film industry. And the reaction of cinema proprietors was indeed – so far, at least, as

an accurate account of it has come down to us – enthusiastic. They were

particularly pleased at the fact that no re-equipping of their cinemas,

or new investment vis-à-vis the older version of CinemaScope, would here

be necessary. The elaborate promises made in the accompanying publicity

– „scenes recorded perfectly, with no distortion“; „a perfect view from

every seat in the house“; „brighter colours; clarity right through to

the back of the picture“ – should, of course, be taken with a pinch of

salt, since the very same promises had been made, in almost the very

same language, at the time of the demonstration performances of 35mm

CinemaScope. One noticeable difference, indeed, was the dropping of the

former emphasis on the three-dimensional qualities of the CS

screen-image („The Modern Miracle! You Can See It Without Glasses“).

Such emphasis was now superfluous, the great competitor in this respect

– 3D – being no longer a factor in the film industry. The Rodgers & Hammerstein musical CAROUSEL was the first film to go into production using the new format, although at the start of filming the new and old formats were used in tandem, with each take being filmed once in CS55 and once in 35mm. A similar method was adopted, moreover, in the making of the first Todd-AO film OKLAHOMA, so that there still at the present day exist two substantially different versions of the film put together from the two different series of takes. The actor originally set to star in CAROUSEL, Frank Sinatra, was not prepared to go through each take twice and quit the project. Gordon MacRae, who also played the lead in "Oklahoma!", took over Sinatra’s role – arguably to the detriment of the finished movie. The format used in the CS55 “roadshows“ has proven in practice something of a technological curiosity due to the fact that it was only ever in these demonstration performances that this particular version of the format was applied. In order to create space for the stereo soundtrack and to limit the mechanical load involved in projection, the pulldown was reduced from 8 to 6 perfs and the image optically reduced. The addition of 6 COMMAG tracks was intended to complete this premium image format with an appropriately impressive high-fidelity acoustics. A series of 50 combination projectors for Century 35/55 were produced and delivered, later being converted and applied also as universal projectors for the Todd-AO format under the denomination: JJ 70/35. Several magnetic stereo apparatuses of the “Penthouse” type, for combined use on 35mm and 55mm COMMAG soundtracks, still survive today. The Sponable Collection at Columbia University also still contains many film-rolls and film-clips both from the 55mm test film-recordings and from the 6-perf performance copies with magnetic stereo soundtracks. It seems, however, that no actual public projections in the 55mm format ever in fact took place. On 15th February 1956, just a day before the CAROUSEL premiere, VARIETY quoted E.I. Sponable as saying that all projections had been in 35mm and with 4-channel magnetic stereo soundtrack, excepting some 12 installations with separate 6-channel magnetic tape player, including those in the New York ROXY and the CHINESE THEATRE in Los Angeles. In the SHOWMEN’S TRADE REVIEW of 25th February, 1956, the news was published that:

Indeed, as late as 17th July 1957 – that is to say, a whole year after

the premiere of THE KING AND I - VARIETY also published the puzzling

news that Darryl F. Zanuck and other members of the Fox Board of

Directors had just seen for the first time this film in 55mm format!

This promise, however, was never kept, because, after the box-office

failure of CAROUSEL, Fox had begun a programme of decisive cut-backs.

Among the many involuntary sins of CinemaScope 55, then, counts the

circumstance that its swift demise deprived the public of the delightful

sight of Sophia Loren climbing out of the waves of the Mediterranean in

order to lend emphasis to the format’s publicity slogan: “More than your

eyes have ever seen.“ (Logo to be faded in here) |

More

in 70mm reading: German Version "Carousel" screening Restoring Cinemascope 55 |

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|