Introduction of CinemaScope |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: David W. Samuelson. Written 2003. | Date: 20.11.2014 |

The

author of this article, David W. Samuelson with his original Henri Cretien Hypergonar "CinemaScope"

lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas Hauerslev The

author of this article, David W. Samuelson with his original Henri Cretien Hypergonar "CinemaScope"

lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas HauerslevThe Panavision company was formed in 1954 to manufacture, supply and distribute anamorphic attachment lenses to the movie theaters across America that did not wish to purchase such lenses from 20th Century Fox. This came about because, with the introduction of CinemaScope earlier that year, there was an enormous need for projection lenses that Fox could not immediately satisfy. Initially, the studio only made the lenses available to theaters that would also agree to install four-track stereo sound systems at the same time. The principle of "anamorphic" imagery - a distorted image that looks normal when restored - goes back to the 16th century. Originally, this process was accomplished by means of drawings or paintings to be viewed (usually) with the aid of a cylinder-shaped mirror. The first patents for anamorphic lenses were granted in the late 19th century. CinemaScope was derived from an anamorphic-lens system created in 1927 by French optical designer Dr. Henri Chretien. It is said that having seen Abel Gance's great picture "Napoleon", which was filmed with a combination of three cameras and projected by three projectors onto three side-by-side screens, Chretien remarked that he could achieve the same result with a single camera and projector, using the optical principle he had developed for tank periscopes during World War I, then only a few years previous. He called his system "Hypergonar" and manufactured a small number of attachment lenses that could be used either in front of a camera lens or for projection. Many of these lenses were destroyed during World War II when Chretien's laboratory was bombed. During the late 1940s, when all of the major Hollywood studios realized that television would make deep inroads into their market, they scrambled for a means to make the cinema experience more spectacular than the format that could be achieved by a television set. The answer was "the big screen." Cinerama (1952), which utilized three projectors, a deeply curved screen and four-track stereo sound, was the first to come and go. Todd-AO used obsolescent Mitchell BFC 65mm film cameras, to which an additional 5mm was added at the print stage to accommodate stereo sound tracks. If nothing else, the format, which was moderately successful for a time, showed that a widescreen aspect ratio with high-quality images - which television could not emulate - was the way to go. Paramount took an option on the French Hypergonar anamorphic system but allowed it to lapse after deciding to proceed with VistaVision, a widescreen system that used an 8-perf-wide 35mm picture, with the film travelling horizontally. |

More in 70mm reading: David Samuelson: A Lifetime with the Movies Visiting David Samuelson The Importance of Panavision The Trail Of The CinemaScope Holy Grail On the Trail of CinemaScope |

Henri

Cretien (right) demonstrates his Hypergonar "CinemaScope" lens to Fox

executives at the end of 1952 in Paris, France. Spyros Skouras (center) and

Earl Sponable (left). Henri

Cretien (right) demonstrates his Hypergonar "CinemaScope" lens to Fox

executives at the end of 1952 in Paris, France. Spyros Skouras (center) and

Earl Sponable (left).Warner Bros. had anamorphic lenses manufactured by Zeiss (one of the original patentees in the 1890s) and called the system Warner SuperScope. At the same time, 20th Century Fox took a serious look at reviving the widescreen Grandeur system it had developed and promoted in 1929-30, but concluded it would not be economically viable. The studio then began examining alternative widescreen systems. When Fox heard that Paramount had dropped its option on Chretien's Hypergonar anamorphic system, a group of senior Fox executives, including Spyros Skouras and Earl Sponable, the studio's technical director, flew to Paris to take a closer look at it. What they saw impressed them, and at the end of 1952 they decided to go with the French system. They called it CinemaScope and decided the format would make its debut with the epic "The Robe", which was already six weeks into production. Subsequently, the show's sets had to be torn down and rebuilt at twice their original width. Fox used the best of the three anamorphic attachment lenses they received from Chretien on "The Robe". (The other two were used on "How to Marry a Millionaire" and "Beneath the 12 Mile Reef".) Each film was shot with a single anamorphic attachment and a single 50mm backing lens. This meant that no wide-angle or longer focal-length lenses were available. The lenses were considered so valuable that each had its own bodyguard. The Chretien system consisted of a "cylindrical" anamorphic attachment to be placed in front of a normal "prime" lens. All three of the lenses were tested. Typical measurements were a change in squeeze ratio across the screen from 1.87:1 in the center of the screen to 2.04:1 halfway to the edge, and 2.37:1 at the very edge. Furthermore, the ratio changed with focus distance, being 2.50:1 at distances greater than 30 feet (9 meters) and shrinking down to 1.80:1 at 5 feet (1.6 meters). When projected at a constant 2:1 squeeze ratio, an actor walking across the screen would become thinner near the edge of the screen, and when photographed in close-up, his face would become fatter. |

|

20th

Century Fox's advertising of the widescreen potential of their CinemaScope

process. Note image size of CinemaScope compared to old standard ratio (the

dotted line). 20th

Century Fox's advertising of the widescreen potential of their CinemaScope

process. Note image size of CinemaScope compared to old standard ratio (the

dotted line).At the same time, Fox asked Bausch & Lomb, an American lens-manufacturing company, to manufacture 250 cylindrical camera attachment lenses as quickly as possible. Although the early Bausch & Lomb attachment lenses were poor and eventually had to be scrapped, those made by Zeiss for Warner's SuperScope system were worse by comparison. In 1954, Panavision founder Robert Gottschalk owned a camera store in Westwood Village, where his customers included many professional photographers and cinematographers. Among his acquaintances was an optical engineer, Walter Wallin, who helped him design a prism-type de-anamorphoser that proved to be far superior to the original CinemaScope cylindrical-type projection lenses. Ironically, Gottschalk and Wallin's lens was based on an even earlier Chretien development. The advantages of the prismatic system of anamorphic attachment lenses were that they were far simpler and less expensive to manufacture, and if the prisms were mounted so that they could be swiveled together, the anamorphic squeeze ratio could be modified. It could easily be set to be 2:1, 1.50:1 and even 1:1 and would remain even and optically true all across the screen. Another advantage was that theaters could build a large reel containing shorts, newsreels and other non-anamorphic films, and an anamorphic film all on the same reel, and could project correct imagery for one or the other at the turn of a small knob - all without stopping the projector. Furthermore, Gottschalk didn't care whether the theater installed four-track stereo sound or not! Within a short time, Gottschalk and a small staff that included Frank Vogelsang, Tak Miyagishima, George Kraemer and Jack Barber produced and delivered some 35,000 prism-type projection lens attachments, until the market became saturated. |

|

Henri

Cretien's original Hypergonar lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Henri

Cretien's original Hypergonar lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas HauerslevIn 1957, at about the same time that the demand for projection lenses was falling off, MGM asked Gottschalk to develop a set of anamorphic camera lenses with a 1.33:1 squeeze ratio for a film called "Raintree County" (1957), starring Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift, with which the studio hoped to outdo Gone With the Wind. The system was called Camera 65. It was later refined, changed to a 1.25:1 squeeze ratio and called Ultra Panavision. Another Camera 65 picture was "Ben-Hur" (1959), the first film shot with Panavision lenses to earn the Academy Award for cinematography. Building upon this success, Panavision developed a system of non-anamorphic lenses for 65mm cameras. They were used on such pictures as "Exodus", "West Side Story", "Lawrence of Arabia" and "My Fair Lady". Meanwhile, by comparison, the cylindrical-type lenses were proving very difficult and time-consuming to manufacture, and Fox was having terrible problems meeting the needs of all the production companies seeking to shoot films using the CinemaScope system. For all of its faults, CinemaScope was very popular with the public, and neither Fox nor Bausch & Lomb could cope with the demand for lenses. The time came when MGM and other companies, no longer wanting to be reliant upon Fox for CinemaScope camera lenses, approached Gottschalk and asked if he could supply 35mm anamorphic camera lenses. Gottschalk had supplied high-quality lenses to many 70mm productions and had worked with many top Hollywood cinematographers, and he knew the cameramen were unhappy about "anamorphic mumps," Cinema-Scope's tendency to make an artist's face look fat in close-up. When Gottschalk came to design his anamorphic camera lenses, he remembered that two prisms in combination could be used to control the anamorphic ratio. He remembered, too, that optometrists had in their drawers of test lenses a special device used to test for astigmatism; it consisted of two thin, circular prisms that could be contra-rotated relative to one another to increase or decrease astigmatism. |

|

Henri

Cretien's original Hypergonar lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Henri

Cretien's original Hypergonar lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas HauerslevGottschalk and Wallin incorporated such devices into their anamorphic lenses and linked them to the focus ring, so that as the distance and focus setting were changed, the prisms would rotate, adjusting the degree of anamorphic squeeze to suit the focus distance. It is said that when Gottschalk first demonstrated his anamorphic lenses at a special screening for senior MGM executives, the entire audience stood and applauded at the end of the screening. Gottschalk patented this device and kept it secret for as long as the patents lasted. There were many others from all over the world who aspired to manufacture anamorphic lenses, most of them using a fairly simple cylindrical lens made by a small manufacturer in Japan. Put behind an off-the-shelf 10:1 zoom lens, they didn't look too bad - it was probably the failings of the zoom lens that hid the shortcomings of the rear anamorphoser. Put behind a good prime lens, they weren't too good. Few attempted to design and manufacture a fixed-focal-length lens with a cylindrical front anamorphic element. It was the battle between Fox and Panavision for the domination of the anamorphic-lens market that was the most bitter and hard fought. |

|

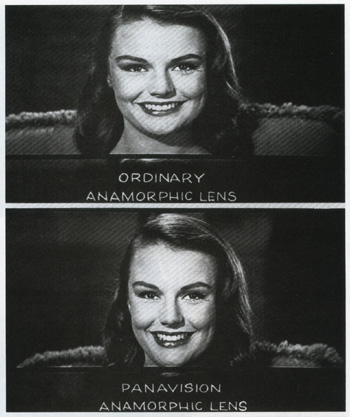

Fox became very upset when Panavision took out full-page advertisements

in the leading trade papers showing a fat-faced actress photographed, it

said, with an "ordinary" anamorphic lens, next to a glamorous picture of

the same actress that was "photographed with a Panavision anamorphic

lens." Panavision engineers also gave hard and gritty lectures and

demonstrations at the ASC and at SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and

Television Engineers) conferences. On more than one occasion, senior Fox

executives wrote to the SMPTE and ASC presidents to complain that

Gottschalk "and MGM had been allowed to use [your] forum to spread

damaging propaganda about CinemaScope." They noted that it was "unfair

to show comparisons of the lenses at close range because that was not

the way CinemaScope lenses were used." In a letter to the president of

the SMPTE, Sol Halperin, ASC, head of the camera department at Fox,

wrote that CinemaScope lenses had "not been designed to photograph

anything at a distance closer than seven feet [2.1 meters]." Fox became very upset when Panavision took out full-page advertisements

in the leading trade papers showing a fat-faced actress photographed, it

said, with an "ordinary" anamorphic lens, next to a glamorous picture of

the same actress that was "photographed with a Panavision anamorphic

lens." Panavision engineers also gave hard and gritty lectures and

demonstrations at the ASC and at SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and

Television Engineers) conferences. On more than one occasion, senior Fox

executives wrote to the SMPTE and ASC presidents to complain that

Gottschalk "and MGM had been allowed to use [your] forum to spread

damaging propaganda about CinemaScope." They noted that it was "unfair

to show comparisons of the lenses at close range because that was not

the way CinemaScope lenses were used." In a letter to the president of

the SMPTE, Sol Halperin, ASC, head of the camera department at Fox,

wrote that CinemaScope lenses had "not been designed to photograph

anything at a distance closer than seven feet [2.1 meters]."Actually, it seems as though Fox foresaw that there would be a problem with close-ups, because in an article published in the March 1953 issue of American Cinematographer, while "The Robe" was still in production, it was noted: "Although close-ups are reproduced dramatically... few may be needed because medium shots of actors in groups of three or four show faces so clearly...." An accompanying illustration showed such a setup. |

|

Henri

Cretien's original Hypergonar lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Henri

Cretien's original Hypergonar lens, November 2014. Image by Thomas HauerslevEventually, Panavision won out, and the day came when Fox ordered Panavision anamorphic lenses for a Fox production. It is an interesting fact that very many years later, after Gottschalk had died, one of the senior Bausch & Lomb lens designers came to work at Panavision and was mortified to discover that some of the "superior" Panavision anamorphic lenses that had caused his previous employer so much grief were, in fact, Bausch & Lomb originals that had been remounted, rebarreled and modified with the addition of Gottschalk's secret astigmatic attachment - and no one at Bausch & Lomb knew! In hindsight, Fox's introduction of CinemaScope proved to be every bit as momentous as the introduction of sound, and the cinema has benefitted from the continued development and perfection of an imperfect original invention. The fidelity of the sound in "The Jazz Singer" (1927) is a long way from the sound we experience in the cinema today, and so it is with anamorphic lenses. Chretien, Skouras, Sponable and Gottschalk would not believe the image quality we see on our screens today. In 1964, Samuelson Film Service Ltd., owned by the author and his brothers, became Panavision's sole overseas representative. Among the early Panavision productions serviced by the London company were "Oliver!", "Fiddler on the Roof", "Star Wars" and "Superman". The author would like to thank Stephen Huntley for information culled from Earl Sponable's collected personal documents on deposit in the Rare Book and Manuscript library of Columbia University, New York, and published in the Film History Journal of September 1993. Thanks also to Kevin Brownlow and Photoplay for the "Napoleon" pictures. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |