2014 Widescreen Weekend Introductions |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Feature film text by: Several. Images by: Anders M. Olsson, Gerhard Witte, Ulrik Rostek | Date: 15.04.2014 |

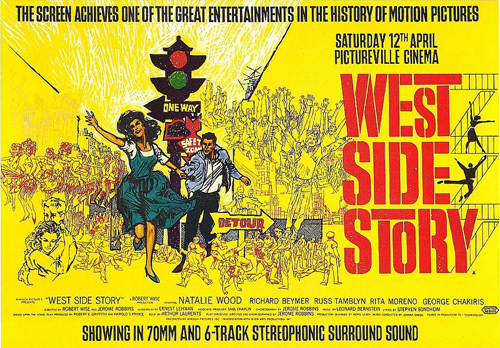

"West Side Story" by Wolfram Hannemann | |

WEST SIDE STORY’s basic concept

is quite simple: take Shakespeare’s classic ROMEO AND JULIET, lift it

from ancient Italy to the back streets of 1960s Manhattan, replace the

Montagues and the Capulets by Jets and Sharks and add lots of singing

and dancing. And as we all know: Shakespeare sells. WEST SIDE STORY

with its brilliant music score by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen

Sondheim and choreography by Jerome Robbins became a huge success on

Broadway. After its opening in 1957 it ran for more than 700

performances at New York’s Winter Garden Theater and had its European

premiere in 1958 at Manchester’s Opera House. WEST SIDE STORY’s basic concept

is quite simple: take Shakespeare’s classic ROMEO AND JULIET, lift it

from ancient Italy to the back streets of 1960s Manhattan, replace the

Montagues and the Capulets by Jets and Sharks and add lots of singing

and dancing. And as we all know: Shakespeare sells. WEST SIDE STORY

with its brilliant music score by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen

Sondheim and choreography by Jerome Robbins became a huge success on

Broadway. After its opening in 1957 it ran for more than 700

performances at New York’s Winter Garden Theater and had its European

premiere in 1958 at Manchester’s Opera House. Being such a big success it was only a question of time and money as when a film version was to be made. Producer Walter Mirish recalls: „ When I first saw the play I thought it possessed all of the elements for an extraordinary film. My enthusiasm was unbounded and, fortunately, the Mirish company was finally able to arrange for the acquisition of the movie rights. Robert Wise was engaged to produce and co-direct with Jerome Robbins; Ernest Lehmen was chosen to write the script and Nathalie Wood, Richard Beymer, Russ Tabmly, Rita Moreno and George Chakiris were chosen to play the leading roles. Shooting began in New York City on August 10, 1960. That day’s shooting yielded the breathtaking, straight down helicopter shots on the skyline of the city which opened the picture. I saw them in a little projection room on Broadway and 49th street the following day, and I immediately developed an excitement in what we were doing that never abated. The production phase of the film in 70mm was long and arduous. The experiment of employing two directors did not work out as effectively as I had hoped. Finally about halfway through the production process we had to dispense with the co-director concept and Jerome Robbins left the company and Robert Wise continued on alone. Fortunately Robbins had already completed the rehearsal of all the musical numbers in great detail and his assistants remained with us. The change speeded up the shooting considerably although it was still a very complicated and difficult subject to transfer to the screen. However, the spirits of all of us who worked on the film were constantly buoyed up by the quality of what we were achieving.“ End of Walter Mirish’s memories. As was the case with all the big movies during that decade WEST SIDE STORY was shot on 65mm negative stock in Super Panavision 70 (referred to as „Panavision 70“ in the movie’s credits). Daniel Fapp served as Director of Photography. It was the first of two feature films on which Fapp used 65mm cameras (the other one being ICE STATION ZEBRA). To allow for low-angle shooting with large 65mm cameras, the interior sets were built six feet off the ground. For the Mirish Corporation WEST SIDE STORY was their first venture into large format photography – and became their nightmare. Not only that shooting in 65mm was very expensive already, but Jerome Robbins‘ extensive re-shooting made it even more expensive. After their experience on WEST SIDE STORY the Mirish brothers refused to use 65mm on any other movie after that. Gladly enough they went back to 65mm in 1965 for WEST SIDE STORY. Most of the original Broadway cast were rejected for the film as either photographing too old or actually being too old for the teenaged characters. Since Hollywood was accustomed to dubbing the singing voices of many stars, dozens of non-singing actors and actresses were tested or considered for the leading roles. Among them: Suzanne Pleshette, Jill St. John, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Ashley, Anthony Perkins, Warren Beatty, Bobby Darin, Burt Reynolds, Richard Chamberlain, Troy Donahue and Gary Lockwood. Director Robert Wise’s original choice for the role of Tony, played by Richard Beymer, was nobody less than Elvis Presley. |

More

in 70mm reading: Widescreen Weekend 2014, images by Ulrich Rostek Attending the Widescreen Weekend from 10 to 13 April 2014 at Bradford's 20th International Film Festival Widescreen Weekend • Widescreen Weekend 2014 • "Audience on Stage" Travel to Bradford Past Widescreen Weekend programs Creating the Widescreen Weekend Projecting the Widescreen Weekend Planning the Widescreen Weekend Internet link: Official Bradford images |

As for the singing, Natalie Wood was dubbed by Marni Nixon. Even though

dubbing Natalie Wood was her chief assignment, Nixon also did one number

for Rita Moreno, which required a relatively high vocal register. Having

dubbed Wood as well as Moreno, Nixon felt she deserved a cut of the

movie-album royalties. Neither the movie nor the record producers would

bow to her demands. Leonard Bernstein broke the stalemate by

volunteering a percentage of his income, a gesture of loyalty-royalty

since Nixon had been a performer-colleague of his at New York

Philharmonic concerts. He ceded one-quarter of one percent of his

royalties to her (which was a generous amount). As for the singing, Natalie Wood was dubbed by Marni Nixon. Even though

dubbing Natalie Wood was her chief assignment, Nixon also did one number

for Rita Moreno, which required a relatively high vocal register. Having

dubbed Wood as well as Moreno, Nixon felt she deserved a cut of the

movie-album royalties. Neither the movie nor the record producers would

bow to her demands. Leonard Bernstein broke the stalemate by

volunteering a percentage of his income, a gesture of loyalty-royalty

since Nixon had been a performer-colleague of his at New York

Philharmonic concerts. He ceded one-quarter of one percent of his

royalties to her (which was a generous amount).Back in these days censorship already played a major part in the release of a motion picture. And it did have quite some effect on WEST SIDE STORY. In the scene on the roof before the musical number "America", when the girls are mocking Bernardo's speech, one of the girls says "We came with our hearts open", and one of the Sharks says, "You came with your pants open!" This line had to be changed to "You came with your mouth open," for the movie to get through censorship. In addition the song "Gee Officer Krupke" was banned by the BBC because of its mentions of drug use and sexual ambiguity. WEST SIDE STORY had its movie premiere on October 18, 1961, in New York City and another one in Los Angeles on December 13 to qualify for the 1961 Academy Awards. Being nominated for 11 Academy Awards it succeeded to win in 10 categories, one of which was the „Best Picture“ award. In this category it had to compete with FANNY, THE GUNS OF NAVARONE, THE HUSTLER and JUDGEMENT AT NUREMBERG. Businesswise WEST SIDE STORY became the second highest grossing film of 1961, just behind Disney’s ONE HUNDRED AND ONE DALMATIONS. Due to the filmmakers‘ request an intermission was dropped before release of the movie in order to create what they termed a „rising tension“ in the story. However, since the print we’ve got tonight offers us the choice to either run it with an intermission or without one, we decided to go the full roadshow way and present WEST SIDE STORY with the intermission plus entr’acte music. I am quite confident that this will in no way spoil your viewing experience. Another nice thing about our print is the fact that the digital audio discs accompanying it represent the original 6-track discrete stereophonic sound mix of the film. You may remember the first time we screened the new print back in 2009 the DTS or Datasat discs just carried a 5.1 re-mix derived from a 4-track source. Even the 70mm magnetic prints made in the 1980s only featured the condensed audio resolution. So tonight you will be able to hear WEST SIDE STORY the way it was intended to be heard from the beginning. And rest assured that you will not find this audio layout on any DVD or Blu-ray disc! Being a real professional director Robert Wise had precise thoughts on how to present WEST SIDE STORY in cinemas. Let me share the letter with you he wrote to theatre owners and management telling them how to do it right: |

|

„Although you will undoubtedly have your own rehearsals with the picture

before your first public showing, the following procedure has been found

most ideal for the presentation of the picture and should be followed as

closely as possible. „Although you will undoubtedly have your own rehearsals with the picture

before your first public showing, the following procedure has been found

most ideal for the presentation of the picture and should be followed as

closely as possible.A special design has been created for the beginning of the picture over which the overture is played. It is of vital importance that the first 4 ½ minutes of this design be projected with the house lights only lowered by 25%. For the proper presentation, please follow these directions: 1. From the start mark the first 28 feet of reel is black. Over this, from the surround horns only, comes the sound of 3 separate whistles The first whistle starts at 12 ½ feet. At this point the curtains should be opened slowly and the house lights lowered by 25%. Since the time required for opening the curtains varies from theatre to theatre it must be timed so that these operations are completed by the time the overture design fades in at 28 feet. Note: if any of the house lights are directed on the screen, it is necessary that these lights go out completely by 28 feet or they will wash out the design when it is projected on the screen 2. At 414 feet from the start mark, when the red color dissolves to the blue, the house lights should be dimmed completely or to the level at which the picture will play. This operation must be completed by the time the title WEST SIDE STORY starts to appear on the screen. It is important that the opening is handled in this fashion. If it is not, if the house lights are dimmed all the way at the beginning, the audience will expect the actual picture to start much sooner then it does. If the opening design is played with the house lights well up the audience will accept the music for what it is – the overture. Please be good enough not to start closing the curtains with the appearance of „The End“ title on the screen. There are still 5 minutes of end „credits“ to be shown before the picture is completed.“ End of Robert Wise’s instructions. Now let’s see what Duncan and his team will make of this. Enjoy the show! |

|

"Remembering Widescreen" by Wolfram Hannemann | |

Working as a film critic judging

hundreds of motion pictures every year I realized that I never ever made

my own film. So I thought why not give it a try and bought my first

video camera back in 2011. During the next two years I trained myself in

using all of the equipment I needed for filming, editing, sound mixing

etc. with a number of small projects, like covering film premieres in my

home town in Stuttgart and making them into short videos. Soon I found

that it is a lot of fun being creative! So I thought that I should even

go a step further and not just cover events, but to do an original

documentary. That was the time when the idea came up to do a short

documentary about the „Widescreen Weekend“. As some of you may remember

I conducted a number of interviews during last year’s „Widescreen

Weekend“, here in Pictureville’s foyer, mostly during intermissions

which was a bit of a stress for me because I also wanted to see all the

films presented during the weekend as well! Before I could start filming

at all quite a lot of paperwork had to be done to get permission to film

inside the National Media Museum. I guess that if I would have known

beforehand I probably would have dismissed the whole idea. Nevertheless

it all worked out thanks to the help of Phil Oates, the museum’s press

officer and I am very grateful for that. Working as a film critic judging

hundreds of motion pictures every year I realized that I never ever made

my own film. So I thought why not give it a try and bought my first

video camera back in 2011. During the next two years I trained myself in

using all of the equipment I needed for filming, editing, sound mixing

etc. with a number of small projects, like covering film premieres in my

home town in Stuttgart and making them into short videos. Soon I found

that it is a lot of fun being creative! So I thought that I should even

go a step further and not just cover events, but to do an original

documentary. That was the time when the idea came up to do a short

documentary about the „Widescreen Weekend“. As some of you may remember

I conducted a number of interviews during last year’s „Widescreen

Weekend“, here in Pictureville’s foyer, mostly during intermissions

which was a bit of a stress for me because I also wanted to see all the

films presented during the weekend as well! Before I could start filming

at all quite a lot of paperwork had to be done to get permission to film

inside the National Media Museum. I guess that if I would have known

beforehand I probably would have dismissed the whole idea. Nevertheless

it all worked out thanks to the help of Phil Oates, the museum’s press

officer and I am very grateful for that. Back home from „Widescreen Weekend“ I immediately had the feeling that none of the material shot there could be used. It would not even be good enough for making a 5 minute featurette! When she saw my desperation my wife came up with the advice that I should put all the material aside and let it rest for some time before working on it. I liked her idea very much, transferred the whole material onto a hard drive and put it aside. If my intro would be a film we would now see a fade out, followed by a fade in to a title card reading „7 months later“. Well, I really don’t know why but it was on a gray Saturday morning in November last year that I felt the urge to watch the „Widescreen Weekend“ footage again. Suddenly it all made perfect sense! And everything was there. Now I knew exactly what to do. Several hours of editing followed and everything worked out so well. The rough cut was finished within one day and it ran no less than 30 minutes! Wow! Incidentially during that time I was approached by Ulrich Rostek, a fellow German and a regular guest at Widescreen Weekend, offering me to use the video footage he shot while staying in Bradford. I watched his material and immediately knew that this was the missing piece I was waiting for. Most of the exterior shots that you will see in the movie were done by him and I am very happy that Ulrich is with us in the auditorium today. A big „Thank you“ to you, Ulli! | |

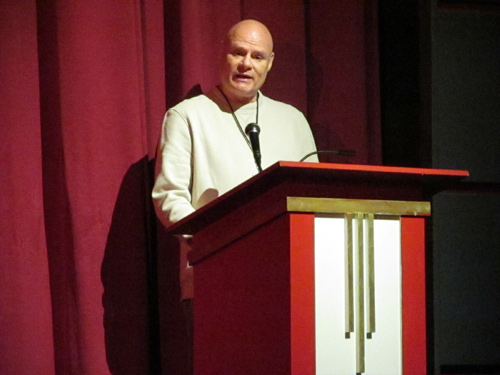

Wolfram

Hannemann introducing film. Image by Ulrich Rostek Wolfram

Hannemann introducing film. Image by Ulrich RostekWidescreen Weekend 2014, images by Ulrich Rostek The fine tuning of my film took most of my spare time during the weeks that followed. During my visit to Bradford last year in December to see THE HUNGER GAMES: CATCHING FIRE in real IMAX, not digital, I brought a preliminary version of my movie on DVD with me and gave it to Duncan for consideration. Originally conceived as a 10 minute featurette to be screened during „Cineramacana“ he was not too happy with its new running time of 37 minutes which would require a separate slot during the festival to screen it. Nevertheless he promised me to watch it. And he did. Which is the reason why I am now standing here in front of you today! Before we screen the film, please keep in mind that REMEMBERING WIDESCREEN is not a low budget production, but more likely a „no budget“ production involving only voluntary work, so please do not compare it to any of the big widescreen epics mentioned in it! I would have loved to interview many more people for my film but time and budget restrictions prevented me from doing so. My special thanks goes to Duncan McGregor and the staff of the National Media Museum for their support, to my second unit cameraman Ulrich Rostek for his exterior shots and to Peter Erasmus of the „Atelier am Bollwerk“ in Stuttgart for letting me use his cinema for test screenings. And last but not least a thank you to each and everybody who was brave enough to talk to my camera. I would like to dedicate this world premiere screening to the one person in my life without whose help and continuous support this project would have never made it to the big screen: my wife Beate. Let me close my intro in the way Lowell Thomas would have done it: „The pictures you are now going to see have no plot. They have no stars. This is not a stage play nor is it a feature picture, nor a travelogue, nor a symphonic concert, nor an opera. But it is a combination of all of them. In fact it is the first public demonstration of an entirely new documentary which I believe is not going to revolutionize the technique of motion picture story-telling. Ladies and Gentlemen – this is REMEMBERING WIDESCREEN!“ |

|

SEARCHING FOR 1956; AN INTRODUCTION TO CINERAMA’S “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” by Randy Gitsch | |

After

David Coles extensive deep dive on the making of this picture this

morning, I will steer away from my usual historical discourse, and share

just a few very personal thoughts watching “SEARCH FOR PARADISE”. After

David Coles extensive deep dive on the making of this picture this

morning, I will steer away from my usual historical discourse, and share

just a few very personal thoughts watching “SEARCH FOR PARADISE”.

It IS that “other” Cinerama 3-panel motion picture. Oh yeah! It’s the one that’s different. Whether you come away enjoying it or not, you’ll certainly grant that’s in the milieu of Cinerama, it’s not so much like the others. The reason for that is simple. This was producer Lowell Thomas’ 3rd and last Cinerama travelogue. Going into production, Thomas was already assured that his inaugural Cinerama release, “THIS IS CINERAMA” was a phenomenon. It was still in release around the world, and had statistically notched it’s belt as the #1 American box-office champion of it’s release year, 1952. Thomas’ 2nd produced Cinerama release, “SEVEN WONDERS OF THE WORLD” was the current headlining Cinerama release picture, and was on it’s way to becoming the 4th highest grossing American release motion picture of 1956. As if the lecturer, journalist, author, broadcaster, director, producer and editor, Thomas needed any more proof of his abilities, his final Cinerama picture was more intensely “his picture”. Of course, he had a full-fledged crew, and collaborators, but Thomas took it upon himself to wear many, many hats in this film’s creation. He was the picture’s main writer as well as its’ on-camera host, and narrator, and…was a contributing musical lyricist? Oh yes…despite not being the director, Otto Lang was, there’s a whole lot of Lowell Thomas in here. Perhaps, a little too much. “Paradise” IS in the eye of the beholder. Lowell will remind us that it is. And from the start of this picture, I become aware that I’m going on another Cinerama vacation. Whoopee! I love to travel. “Show me the paradise”, I say to myself. Except one after another, the destinations in this picture aren’t what I was expecting. In this picture were going to go hiking, and white water rafting, and even parachuting. In other words, dusty, cold and wet. So if that kind of wonder-hunting is on your bucket list, “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” should get your adrenaline flowing. Perhaps you’ll unpack your bags, and enjoy the journey. But I long to remain on the plane looking out the window, flying over many of these places, or back at the base camp enjoying the beautiful stationary view around me. And in that regard, the Cinerama is as beautifully panoramic as ever. |

|

David

Coles mentioned how the late Jim Parker’s death during the shooting of

the Indus River rapids rafting sequence, led to him being absent from

much of the picture or replaced in some scenes by a “stand-in”. On this

level, viewing “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” can be akin to watching

MGM’s 1937 Clark Gable feature, “SARATOGA”, and the late Jean

Harlow’s stand-in, Mary Dees covering for Jean wearing a big floppy hat

concealing her face, or holding binoculars up to her face, or seen

conspicuously only from the back. You may find yourself looking deep

into “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” scenes to see you can spot Jim Parker,

or the “real” Jim. It’s kind of like looking for vestiges of Tyrone

Power in the long shots in “SOLOMON AND SHEBA”, or enjoying

director Ed Wood’s wife’s chiropractor doubling badly for the Bela

Lugosi in “PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE”. Maybe it’s not…that much

fun. For example, early on in “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” you’ll see

the stand-in for Jim Parker seen sleeping, which he seems only able to

do with a hat over his face…aha, a clue. In other scenes, when “Jim”

passes close to the camera, his head is bowed down, such that the brim

of his hat conceals his face, and I wonder. David

Coles mentioned how the late Jim Parker’s death during the shooting of

the Indus River rapids rafting sequence, led to him being absent from

much of the picture or replaced in some scenes by a “stand-in”. On this

level, viewing “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” can be akin to watching

MGM’s 1937 Clark Gable feature, “SARATOGA”, and the late Jean

Harlow’s stand-in, Mary Dees covering for Jean wearing a big floppy hat

concealing her face, or holding binoculars up to her face, or seen

conspicuously only from the back. You may find yourself looking deep

into “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” scenes to see you can spot Jim Parker,

or the “real” Jim. It’s kind of like looking for vestiges of Tyrone

Power in the long shots in “SOLOMON AND SHEBA”, or enjoying

director Ed Wood’s wife’s chiropractor doubling badly for the Bela

Lugosi in “PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE”. Maybe it’s not…that much

fun. For example, early on in “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” you’ll see

the stand-in for Jim Parker seen sleeping, which he seems only able to

do with a hat over his face…aha, a clue. In other scenes, when “Jim”

passes close to the camera, his head is bowed down, such that the brim

of his hat conceals his face, and I wonder.All movies, like our own lives, are of a time and a place, and “SEARCH FOR PARADISE” is firmly set in a thankfully narrow sliver of the Cold War. Like other Cinerama travelogues, the latest American Armed Forces hardware, like the Air Forces’ F-104 “Starfighter” and the F-100 Sabrejets, are on ample sabre-rattling display here. But in this picture, the Lowell Thomas narrative is ratcheted up to a new jingoistic high point, whenever Thomas sees an invited Chinese guest at King Mahendra’s Nepalese coronation. No less than 7 times, they’re the “Chinese Reds”, from “Red China”. Oh, and they’re wearing those “severely cut black robes, the uniform of communism”, and “grim” he calls them, and “again…in black” he adds. Well…tisk, tisk, Lowell. Get over it. They’re probably looking at you and thinking the fedora makes you look goo fee. After all, they are Nepal’s neighbors. Americans are not. One penetrating thought I have is that of a catch-phrase coined by the American humorist, webmaster and writer, Jon Hein. That phrase is “jumping the shark”. The analogy stems from an episode of the classic, set-in-the-1950’s American TV series, “HAPPY DAYS”, which was kind of funny, kind of fun. Until that one episode when the motorcycle-riding, leather-jacket wearing, greased back hair-styling, ever cool, “Fonzie” went on vacation, and went water skiing…uh, with the jacket on, and literally jumped a shark on water skis. “Jumping the shark” is that moment, then, the exact moment when something goes wrong, when something goes bad. In Act 2 we are treated to the 3rd and last musical ditty that Lowell Thomas has written lyrics for, this picture by the way, being his first and only credit as a lyricist. As Lowell is water taxied out to a waiting houseboat restaurant on Kashmir’s Dal Lake, christened “Buckingham Palace”, his self-awareness and hubris will be put to poetry. Right about then, I swear that houseboat must be surrounded by dorsal fins. Because at that moment, Lowell Thomas’ career as a musical lyricist will jump the shark. Despite Lowell’s heavy-handedness, one truism of Cinerama trumps him. That is the Cinerama process is always the star. This new remastered version now let’s you see a panoramic paradise looking better than it’s looked in over 50 years. Enjoy the Cinerama! |

|

White Christmas by Tony Sloman |

|

1.

“Holiday Inn” clip 1.

“Holiday Inn” clip“White Christmas”, words and music by Irving Berlin – you saw Marjorie Reynolds – many of you will remember her as William Bendix’s long-suffering wife in the television series “The Life of Riley”, or perhaps as Ray Milland’s co-star in Fritz Lang’s “Ministry of Fear” – together there with Bing Crosby, in the dramatic climax of the 1942 Paramount wartime musical “Holiday Inn”, and you also glimpsed Crosby’s real co-star, Fred Astaire, at the end, there, with Walter Abel. “Holiday Inn” was a smash-hit in its day; each song was tailored to a specific American holiday, and in 1942 each holiday was tinged with wartime relevance. Did the fake film setting of the Holiday Inn itself look familiar? Well, as surely as film feeds upon itself, that was the actual set of the inn re-worked as the inn featuring in the film within a film. And in the film that you’re about to see - “White Christmas” itself, you’ll recognise yet another re-working of the very same set, twelve years later! “Holiday Inn”’s success was immeasurable. The Irving Berlin score resounded with hits, none more successful than “White Christmas”, the recording of which by Bing Crosby was to become the biggest selling, most successful popular single record of all time, especially after America’s entry into World War II, when the song took on a new simultaneously wistful and prophetic tinge, Bing Crosby’s voice seeming to capture a nostalgia for peacetime and the soldiers retuning from the war fronts far, far away from the USA itself. The “Holiday Inn” teaming of Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire also proved popular, and Paramount set about to re-team them, this time using a wispy plot centred on the Irving Berlin songbook, only this time they would film in Technicolor, almost mandatory for screen musicals by 1948, although no studio could equal the taste and style of Paramount’s rival, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, MGM itself. Crosby and Astaire had done much charity work during the war, work that was both risky and dangerous, and here in Europe both men played army bases, and performed under fire. Paramount, not missing a trick, incorporated similar moments into the scenario of their new Technicolor musical, which was to be called “Blue Skies”, appropriate title since it appeared post-war, when the skies themselves had been cleared by the Allies, and since it utilised many existing compositions by Irving Berlin. And yes, room was found in the film’s narrative for Bing Crosby to croon “White Christmas”: here’s that oh-so-nostalgic clip from “Blue Skies” – 2. “Blue Skies” clip Needless to add, sales of “White Christmas” by Bing skyrocketed once again, and Bing and Fred Astaire proved, for the second time in Paramount’s history, to be a viable and commercial screen partnership: it would make sense to team them for a third time, and so Paramount commissioned yet another picture to feature Irving Berlin’s music, only this time it was to be an original, and hopefully topical, score, but was also to include that now hardy perennial, “White Christmas” itself. When George Gershwin was allegedly asked by a journalist, “What was Irving Berlin’s contribution to American music?”, Gershwin replied, “Irving Berlin is American music” – and at the time Paramount were mooting the film of “White Christmas”, Irving Berlin had just completed two of the most successful Broadway musicals ever – “Annie Get Your Gun” and “Call Me Madam” (filmed by MGM and 20th Century-Fox respectively) and among his own successful films include two huge hits, each based around his own songbook: “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” and “Easter Parade”. Paramount commissioned a new score from Berlin for the film that was to be entitled “White Christmas”, after his biggest (and bigger than anybody else’s!) greatest hit. Since “Holiday Inn” had been based on an original idea by Berlin himself (and is duly credited), Paramount had to pay him again for the remake rights. Additionally, the wily Berlin also insisted on a possessory credit: in all advertising the film would be referred to as “Irving Berlin’s White Christmas”. Although Berlin didn’t physically write the screenplay – that was credited to up-and-coming producer-directors Norman Krasna, Norman Panama, and Melvin Frank – it was Berlin’s idea to utilise a serious, and then very contemporary, theme. What happens to a high-ranking army officer when the war is over? In these pre-“West Side Story” days, a very serious theme indeed for a musical. The plan was to re-team Crosby and Astaire, naturally, and seek a well-known “serious” actor for the forcibly-retired General, and Dean Jagger, who had just won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in “Twelve O’Clock High” was suitably cast. But by 1953, the movies themselves were changing: television had grabbed the once-vast Saturday night audience, and perhaps Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire might not be quite enough to pull in the crowds. Paramount could provide one of Hollywood’s best directors: Michael Curtiz, he of “Casablanca” and “Yankee Doodle Dandy”, had decamped from Warners to Paramount, and was available, and there was something else on the horizon: cinema screens were growing bigger to combat television, and Paramount realised that as well as Crosby, Astaire, and now Irving Berlin songs, something else, something “special”, yet perhaps intangible, was needed to guarantee both commercial and critical success. And then Fred Astaire pulled out. Although he had agreed to appear in the film in late 1953, Fred became ill, and temporarily uninsurable, and was swiftly replaced by Donald O’Connor. But Paramount already had another big star under contract, a musical comedy star who they’d just loaned out to Samuel Goldwyn, and who had scored a smash success with “Hans Christian Andersen”: Danny Kaye. But Kaye was most definitely a solo item – how would he react to co-starring with Bing Crosby? Wasn’t Bob Hope more Bing’s stooge? And Kaye was no stooge. But when Kaye realised he would be directed by Curtiz and would be singing Berlin, he was in, to Paramount’s relief. And there was that something else, that something very special, that we are all here, 70 years later, to celebrate. 20th century-Fox had achieved a tremendous success with its new anamorphic screen process entitled CinemaScope, and the other studios were impressed. Paramount, however, decided it was time to develop their own process; after all in those early days of ‘Scope there were, indeed, mitigating factors against its use: anamorphic lenses, high grain, poor focus, low depth of field...all, of course, corrected in time. Paramount remembered a film process that dated way back to 1928, a process once-known as Panoramico Albertini, that utilised a regular 35mm frame but which exposed, and subsequently projected, a double 35mm frame in the camera horizontally, and projected it likewise – voila, instant 70mm! Paramount researched into their own past, and after experimentation developed the so-called Paramount Lazy 8 Butterfly Camera, and renamed the process – VistaVision. With a variable ratio, prints would be provided for projection at 1.85:1 or even ‘Scope ratio (or as in today’s 16:9 widescreen television releases on DVD or BluRay) but they would not require an anamorphic lens. ‘Scope prints were, in fact, provided for early engagements, and the system was to be incorporated in the filming of “White Christmas”. How important was it to the success of that film? Very. 3. “White Christmas” Theatrical Trailer “White Christmas” premiered, in VistaVision, at the Radio City Music Hall, New York, on April 27th, 1954, with a unique horizontal 35mm print and a special projector resulting in a huge image with an aspect ratio of 2:1. Yes, exactly 60 – count ‘em – 60 years ago. Why did “White Christmas” premiere at Springtime? Only Paramount’s marketing department could have answered that question, but it has remained a Christmas perennial ever since. The casting of Danny Kaye helped ensure its success, and also its timelessness. Kaye’s “camp” chimes beautifully with Crosby’s understated performance, and he can clearly handle Robert Alton’s choreography – oh, and among the chorus boys watch out for the uncredited George Chakiris, whose Oscar-winning performance you are about to witness soon in “West Side Story”. Incidentally, among the chorus girls is the talented Barrie Chase, who would partner Fred Astaire in his Emmy-winning television specials, “Another Evening with Fred Astaire”, “Astaire Time” and “The Fred Astaire Show”. Watch, too, for WC Fields’s stooge Grady Sutton in a party scene, and the self-styled Mayor of Hollywood, the uncredited Johnny Grant, as one Ed Harrison; clearly a jab at the – then – all-important Ed Sullivan. Oh, and the GI in the photograph is ex-“Our Gang” member Carl “Alfalfa” Switzer, and Garbo’s leading man Gavin Gordon plays the uncredited General Carlton in the film’s finale... But you don’t need me to point out the other pleasures of this classic in the wonder of VistaVision: here, in all its Technicolor glory, is “White Christmas”. |

|

“The Way We Were” by Tony Sloman |

|

October 24th, 1973, and, frankly, all any audience needed to know:

Streisand, Redford, the Title. The movie cost Columbia approximately 5

million dollars, and returned over 22 million profit in immediate

theatrical screenings alone. It received six 1973 Academy Award

nominations, and took home too: Best Music and Best Song. If there were

an Oscar for Best Romance, then that’s what it would have won, hands

down: a screen romance which, with hindsight, almost rivals those of

Scarlett and Rhett, Armand and Camille, Vronsky and Anna Karenina. For

sure, they all have one particular resonance in common, as you’ll see in

a little while... October 24th, 1973, and, frankly, all any audience needed to know:

Streisand, Redford, the Title. The movie cost Columbia approximately 5

million dollars, and returned over 22 million profit in immediate

theatrical screenings alone. It received six 1973 Academy Award

nominations, and took home too: Best Music and Best Song. If there were

an Oscar for Best Romance, then that’s what it would have won, hands

down: a screen romance which, with hindsight, almost rivals those of

Scarlett and Rhett, Armand and Camille, Vronsky and Anna Karenina. For

sure, they all have one particular resonance in common, as you’ll see in

a little while...But “The Way We Were” could have been so much more, so very much more. And the material which would have ensured the film’s greatness, not merely its enduring popularity, was actually written, filmed, edited – and deleted. And fortunately preserved, and not junked, as was the almost inevitable fate of many post-preview thematic deletions. Let’s take a minute to explore the genesis of “The Way We Were”: film producer Ray Stark was the son-in-law of the great Ziegfeld comedienne Fanny Brice, and, determined to tell her story as a musical, first as a show, then as a film. Arthur Laurents was a noted Hollywood screenwriter, with such successes as “The Snake Pit”, “Rope” and “Summer Madness” behind him, and would write the books for two of Broadway’s most fabulous successes – “West Side Story” and “Gypsy”. But Ray Stark had great trouble in finding a suitable Fanny Brice. Arthur Laurents, on the other hand, was directing a Broadway show called “I Could Get it for you Wholesale”, which featured a young Barbra Streisand, who was stopping the show every night with her solo number “Miss Marplestein”, back then in 1963. And she was seen by producer Billy Rose, who brought her to Ray Stark's attention: the rest was show business history, and the show was called “Funny Girl”, which was subsequently filmed, bringing Barbra Streisand a – shared – Best Actress Academy Award. Streisand kept in touch with writer-director Arthur Laurents, who once told her that she reminded him of a young communist he had known at Cornell, whose name, amusingly, was Fanny Price, a fiery new Yorker who was a political activist, even though the Young Communist League at Cornell consisted of only 12 members – and what would’ve happened if that young Jewish girl had fallen for another acquaintance of Arthur’s, known cryptically only as Tony Blue Eyes...? Ray Stark had produced a second success with Barbra Streisand, 1970’s “The Owl and the Pussycat”, and he was looking for another vehicle that would re-unite him with her. In the meantime, Arthur Laurents had written a 50-page treatment which he had called, sensibly and literally, “The Way We Were”, confidently expecting to change the title to a more glamorous, more dramatic one, some day. Stark purchased the screen rights from Laurents and sent the treatment to Streisand. In the treatment, Arthur Laurents had incorporated much of the hell that he and others had been subjected to in the era of the US government “blacklisting” of subversives in Hollywood: ostensibly to root out communists and their influences, it turned into an anti-Semitic witch-hunt to root out Jews and liberals from Hollywood and also US TV (the theatre, in particular Broadway, was more difficult to deal with: there was hardly anyone in new York who was not a Jew or a liberal!) Barbra Streisand liked the treatment very much, and agreed to make the picture, and Laurents was hired to write the script, which was to feature the Hollywood blacklist prominently as a background to the romance between the young blonde, blue-eyed WASP and his Jewish left-wing sweetheart. To direct the film, Stark hired Sydney Pollack in 1971, coming off the success of “They Shoot horses, Don’t They?”; a former actor, Pollack had worked with Robert Redford in “War Hunt”, and had achieved success directing Redford in such films as “This Property is Condemned” and “Jeremiah Johnson”. Pollack knew there was only one choice to play the lead opposite Barbra Streisand – his old pal Robert Redford. But Redford had read the treatment and had already turned it down. Pollack then spent the next six months trying to change Redford’s mind, which eventually Ray Stark managed to do in virtually one single afternoon: in June 1972 Stark called Pollack and told him that he had exactly one hour to convince Redford, otherwise they would commit to Ryan O’Neal. Redford put his reservations on the table – strengthen Hubbell’s character, invest more in the witch-hunt politics of the time, give Hubbell a key point of view – and both Pollack and Stark agreed. Shooting began on September 18th 1972, and was completed on November 29th, 1972. “The Way We Were” became one of the only 6 features to prominently deal with the Hollywood blacklist – for the record, the others were “The Front”, “Guilty by Suspicion”, ”Fellow Traveller”, “The Majestic” and “Good Night and Good Luck”. At least openly – there are also “naming names” closeted films, notably “On the Waterfront”, and “Spartacus”, but they are another story. The blacklist sequences in “The Way We Were” proved too strong for preview audiences. Let’s hear what director Sydney Pollack, screenwriter Arthur Laurents and Barbra Streisand herself have to say... Extract 28:16 Start Sc. 199 – Trim CU Katie "In college..." incorporating interviews with Sydney Pollack and Arthur Laurents, plus Sc. 169 - Lifts “...and I think the picture suffered” END (NB slight unavoidable dialogue overlap with girl in yellow entering R to L) 30:36 Note the American film terms "Trim" and "Lifts" on the out-take surrounds. In English, we used the expression “deletion” – and there were many of them between the so-called “final” cut of “The Way We Were” and the actual delivered version which went out on release. Normally such deletions are junked and not stored, but thanks to Barbra Streisand she kept every deletion, and they are available on the excellent documentary “The Way We Were: Looking Back”, on the original DVD reissue release. So what you are about to see tonight is a brilliant new 4K copy of the released version of “The Way We Were”, the one many of you will already be familiar with, but I’m going to leave you with this thought: would it not have been possible to release this time a 2-disc set: the release version and the uncut preview version, simply by incorporating in straight cuts the deletions rescued by Barbra Streisand? Generally, deletions made at previews, and additions, are sensible and audience-driven, but in this particular case a key aspect of the film is missing, and would certainly add to the movie’s heft. You’ve seen earlier in the trailer what the distributors were selling, and who could blame them – the box office proved its worth. I’m going to leave you with another excerpt from the documentary “Looking Back”, where the film’s makers explore their own particular points of view: the film isn’t at all lessened by what you are about to see – it’s still a very moving, very relevant motion picture, but perhaps, just perhaps, it could have been a very great one.... Extract 39:42 CU Sydney Pollack: “We had two pictures in San Francisco...” (Directly after “In such a black and white way as...”) Including Arthur Laurents: “But the climax is missing...” Barbra Streisand: “There weren’t many movies where...” Sydney Pollack: "I feel that...clean line emotionally to the picture the way it is now" End on BCU Streisand and Redford facial two-shot (before dissolve through to Marvin Hamlisch) 42:16 By the way, they never did manage to change the title. Thank you. |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|