Rick Mitchell Interview

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Ramon Lamarca Marques, 65/70mm Workshop | Date: 06.07.2008 |

|

His work has appeared in American Cinematographer, Films In Review,

International Widescreen, MovieSound Newsletter, Los Angeles Times, The

Operating Cameramen Magazine, The Perfect Vision, Cinefantastique, Film

History, and Weekly Variety as well as additionally on the

fromscriptodvd.com and

hollywoodlostandfound.net websites. He is also a film editor and occasional director, a graduate of the University of Southern California Department of and lives in Southern California, USA. |

More

in 70mm reading: Rick Mitchell - A Rememberance Who is Rick Mitchell? 65/70mm Workshop |

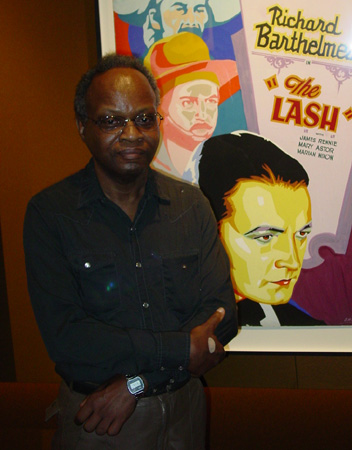

Rick

Mitchell in 2007, as seen through Paul Rayton's lens. Rick

Mitchell in 2007, as seen through Paul Rayton's lens.Dear Mr Mitchell, Thank you for accepting to be interviewed by the 65/70 workshop. Question: I would like to start the interview by analysing the evolution of cinema technology. If one compares the peak of cinema technology in the 60s with systems as Todd-AO and five speakers behind a huge curved screen with what we have today, we could conclude that broadly speaking cinema technology has not progressed, whereas TV presentation with HD and stereophonic sound has clearly progressed. Do you think that this lack of progress in cinema technology as compared to the advances in TV technology has affected cinema attendances? In other words, if cinema had progressed as much as TV has from the 50s, which cinema technology should we be enjoying in theatres these days? Answer: This is an issue to which I've been giving a lot of thought over the last 20 years. There are historical, sociological, and economic issues involved that I have rarely seen considered. My perspective, of course, is from the American cinema, but because of Hollywood's dominance of the world market, decisions made over here have ultimately affected world cinema as well. I think the problem is not the lack of progress in cinema technology, but the unwillingness of those who hold the purse strings in both production and exhibition to adopt and promote new film related technology. In the Eighties, not only did exhibitors make no effort to combat the hype for home video, even when it was putting down theatrical moviegoing, they continued to divide up older theatres or only build tiny new ones despite comments from the public that they preferred the big screen, big auditorium experience. Back in 1992, I saw a promo for "Far and Away" that Ron Howard and Brian Grazer had made for exhibitors, which showed the same scene as it would appear on tv, in 1.85 and 70mm (it was actually a 35mm anamorphic presentation). Yet, with their typical stupidity, Universal based its publicity campaign around Tom Cruise, which, because of the nature of the film, ultimately hurt its box office. If they'd played up the original 65mm photography, they would have gotten people in their Forties and Fifties who weren't particularly interested in Tom Cruise, but would have come to 70mm presentations because of fond memories of the 70mm roadshows of their youth in the Sixties. The reason cinema has not really advanced in the last 40 years is because the decision-making executives at both the production and exhibition ends are totally out-of-touch with moviegoing audiences, and unfortunately, because they are better educated than the executives who founded the industry, most of whom came out of the audience they were making films for, and are overly influenced by critics and academics, who also are not only out of touch with audience taste, but are constantly, and futilely, trying to influence them. Generally ignorant of its various technologies, they overlook the fact that these technologies, including Wide Screen, are what make cinema an art form, and when properly used, enhance the theatrical audience's experience of the film, as with most of our memories of the great 70mm roadshows of the early Sixties. |

Internet link: |

| RAMON: What I was trying to convey with my question is that in practical

terms cinema exhibition has regressed from its heyday. Instead of

Todd-AO we have now many productions being done with cropped 35mm or

with scope 35mm but the image downgraded by 2k digital intermediate.

These two are the main two technologies used nowadays, which are a huge

step backwards from Todd-AO. We no longer have big screens (or very few

indeed), instead of five speakers (and five channels) of stereophonic

sound behind the screen we have three. In many places the screen is

bigger for the ads than the main feature in scope. The list of

regressions is endless. And so, cinema technology, in practical terms

has gone backwards, and Television technology has gone forward. No

wonder cinemas are empty. RICK: My point-of-view on the subject seems to come from a slightly different perspective than yours, others with whom I've discussed this, or the authors of other writings I've seen on this subject, in that I have been "in the room" as contemporary decision making executives have "excreted their ignorance", shall we say. This was in the Seventies, but these were the precursors of their even less informed successors of today, all of whom were a far cry from those executives in charge in the key year for this discussion, 1953. Though, while ongoing development has been done in new presentation processes, though I don't know if much has been done in film over the last five years, implementation of these developments is dependent on the willingness of theatres to spend the money to put them in and studio executives to make films in the process. To expand on my above comment about contemporary executives, they do not have the kind of emotional connection to the theatrical moviegoing experience that their counterparts had 55 years ago, which was responsible for the enthusiasm for wide screen and 3-D particularly by Jack Warner and Spyros Skouras. Additionally, these executives have been educated in a higher education system that until the Seventies was hostile to film and has subsequently imposed its own artistic standards on film study, standards which subvert those technological aspects which make film a unique art form. Thus, they are really unconscious to the idea that the proper use of widescreen and stereophonic sound, for example, really does enhance the experience for the audience. If they make the effort to see Cinerama, or "LAWRENCE OF ARABIA", "THE SOUND OF MUSIC", or "2001" in 70mm, they dismiss this as old technology for old movies, irrelevant to today. Where independently financed entrepreneurs have financially demonstrated the viability of their technological advances, no matter how technically flawed, as with Dolby and its Stereo Variable Area sound track in the Seventies, or IMAX's conversion of 35mm features to its process, the industry jumps on that bandwagon, but will not take chances on anything on their own. It might be noted that Digital Cinema was developed outside the industry. 2K Digital Intermediates for anamorphic films have been a major pet peeve of mine, but today's executives and filmmakers rarely see the high image quality possible with even 35mm film, since even $300,000,000 films now do not print film dailies, so the filmmakers don't see a film image until they see the answer print. After watching the film on low resolution video for so long, even Super 8 film prints of the quality of some I've gotten from Derann in England would look good to them on a big screen! RAMON: There is certainly an unwillingness from the industry to use the best of cinema technology as you say. I have read about Super Dimension 70, which I believe you have seen, and Maxi-Vision 48, and I think these are the two only major developments in terms of cinema technology, apart from, of course, the improved film quality. But the industry has paid very little attention on them. I do not rate digital exhibition at 2k as a development since it really brings very little, if anything at all, and for some of us it even detracts from the cinema experience. RICK: I have seen not only original Super-Dimension 70 several mind-blowing times, but also the conversion, admittedly through a DI process, of 1.85 and digitally shot material to it, which also looks terrific. I don't know anyone whose seen Maxivision, or if it's still being promoted, but I think it was a mistake, since retaining the 1.85 image really does not make it much different from HDTV. In the last couple of years I've seen "THE SEARCHERS" and "THE HIGH AND THE MIGHTY" projected digitally from highest quality master tapes. Both looked okay, and I sit very close, but I would like to see a film restoration for comparison. I know these digital versions were done because of problems with the original negatives and protection separations, but I have seen a film print of "THE SEARCHERS" from a film preservation made within the last 30 years and it looked quite good. However, the pro-digital camp seems determined to not allow that to happen. |

|

| RAMON: The splitting of old theatres in the 80s was a disaster. I think

it put many people off of going to the pictures again. However, I would

not blame the exhibitors only, because of changes in trends during the

seventies they hardly had any product to use their big screens properly.

After investing in 70mm equipment, 65mm productions almost disappeared.

Some people argue that blow-ups kept 70mm alive; I think that they

actually killed 70mm since audiences thought they were seeing 70mm

regardless of the origination (65mm,

Technirama, scope 35mm or cropped

35mm) and frankly only the first two are visually amazing and excel over

cropped 35mm or scope 35mm prints. RICK: The reasons why splitting up theaters came about in the US is a bit too complicated to go into here, rooted in a misconception about the composition of the youth audience, but to continue to do it after it was clear that even young audiences disliked it, and with tv screens getting larger, was totally stupid. 65mm production declined supposedly for reasons of cost, though I'd doubt it was a fraction of the final budget of "Cleopatra". The roadshow cache was still strong enough in the Sixties for the studios to blow up 35mm anamorphic and later 35mm spherical films for special initial engagements, but that essentially went out in the U.S. in the post-1970 anti-roadshow backlash. The blowups done between approximately 1980 and 1994 were for sound, not picture, as the Stereo Variable Area process lacked the dynamic range and stereo discreteness possible with magnetic sound. RAMON: Would you favour reviving an old system (i.e. Todd-AO, Dimension 150, Super Technirama 70) or investing in a new system like Super Dimension 70? RICK: I would be in favor of both. In fact, given the blindness of the American film industry, a number of us had been hoping some visionary European filmmaker aficionado of 65mm would do a mainstream film whose success would open Hollywood's eyes to the possibilities. But if articles in the American Cinematographer are any guides, European filmmakers have, shall we say, "ingested digitalis" even more than their American counterparts. |

|

| RAMON: You mention that contemporary decision-makers are ignorant as

compared to those of the 50s and I agree. Nevertheless, I fail to

understand how someone like Steven Spielberg who is both a film maker

and a producer with a great knowledge of film history has never used

65mm negative for any of his productions (apart from short special

effects scenes). I think the closest he was to this was when preparing

to shot Empire of the Sun, which could have been shot in 65mm. Also, I think that producers nowadays are aware that a big (if not the biggest) slice in profits from their movies will come from the TV and DVD market and therefore they probably think 35mm is good enough. I think that they neglect the fact that with 65mm printed on 70mm they would maintain their TV and DVD market but would increase their theatre market. Unfortunately, I do not think anyone has so far published an economic study on the costs of shooting in 65mm compared to 35mm (including 70mm prints distribution) and if this could be recovered by the extra box office returns, although within the Workshop we have done outline research that shows cost is not an issue for big budget productions. Also, 65mm material could make the HD definition at home even better now that there is blue ray. I have often wondered how a 70mm print produced using Technicolor’s proprietary dye transfer system (something never done) would look. RICK: As I mentioned before, whatever future there is for 70mm will have to come from outside the mainstream production industry, possibly from outside the United States. It will take the right very entertaining dramatic film that shows off the sharpness and clarity possible with 65mm production. Depending on the subject matter, it may need stars, which would add more to the cost than the 65mm process. It would probably have to be a family-friendly project for maximum commercial impact, but with a strong appeal to the key 15-24 year old audience. The producers may have to four-wall the picture over here, that is, booking it themselves into theatres like the Cinerama Dome and similar theatres and, assuming it's successful, using that to excite other theatres still equipped for 70mm projection to book it and others to consider putting in 70mm projectors. I get the impression from Thomas Hauerslev that it would be easier to get such a film booked on the European continent. Success may get it a distribution deal with a significant company and get the studios to consider future 65mm production. Failure would probably be the final nail in 65/70mm’s coffin. I'm not aware of any producer or director in the Hollywood-oriented business today who has the clout to convince a studio to shoot a film in 65mm and release it with 70mm prints except Spielberg, who hasn't been interested in this type of film for the last 20 years; I was happy to learn the new “Indiana Jones” film was shot anamorphic, though I still worry that it won’t use the format as expansively as he did in the Seventies. But exhibition has shown a willingness to respond to anything that will put bodies in their theatre seats, and that's why I feel that the right 65mm film could do this, a sentiment which also applies to Super Dimension 70. RAMON: I am surprised Steven Spielberg has not embraced the 65/70 format, since it would suit his cinema very well. The ever-present “roller coaster” rides in Spielberg’s films would be very well suited by 65/70. RICK: Spielberg's attitudes are very complicated. According to some people I know who've worked with him over the last thirty years, in the early Eighties he became very conscious of his image as a maker of "frivolous" films and began to desire the kind of respect then being accorded the "serious" directors of the early Seventies, most notably Martin Scorsese. These directors were strongly influenced by European filmmakers of the Sixties, few of whom worked in anamorphic to any degree, much less 65mm, and similarly none of these directors but Francis Coppola ever worked in anamorphic, even though some of them acknowledged their affection for David Lean and "LAWRENCE", and some even the roadshow films in general. Critics, who've always been the biggest opponents to film technological advancement, associated not only wide screen, but color, with the then much-hated Hollywood. In recent years, many of these directors have worked in Super 35, but they usually treat it as a more tightly letterboxed 1.85. Spielberg has never shot any of his serious films in anamorphic or Super 35 (this may in part be do to the influence of his long time cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, whom I believe doesn't like anamorphic lenses), and as I mentioned, stated in an interview, I believe during "JURASSIC PARK", that he now sees in 1.85. |

|

| RAMON: I fail to understand why film companies have not promoted 65/70

more, like for example giving incentives to the right films to be shot

in 65/70, this could promote the format and thus the survival of film as

a medium for several years to come. Have they just given up because they

think digital imaging will take over very soon? RICK: As I've stated before, the problem rests with the current executives, most of whom have probably never seen a 70mm print from original 5 perf 65mm photography; they've probably seen Imax and accepted its hype. To them, 70mm means "high quality sound" and with digital, they can have that with 16mm (The DTS process has been used with 16mm prints). This is why I say that any future 65mm has, and this also applies to Super Dimension 70, will come from outside the industry, as was the case 50 years ago with Cinerama and Todd-AO. With the right film project, exhibitors can be found who will show it, especially if somebody else pays for the marketing costs and equipment installation, and if the film is successful, the industry will take notice. But if it doesn't, it'll be the death knell of 5-perf 65mm, I'm sorry to say, as the failure, even if it's a mistake like Kenneth Branagh's "Hamlet", will be used against any future attempts to revive it. RAMON: Sorry, probably I was not very clear with my last question. When I referred to film companies I meant film stock producers like Kodak not film studios (which is a subject we have already mentioned as you say). It surprises me that companies like Kodak have not offered 65mm for the price of 35mm to any major studio for a big production. This would be their best publicity, to get a big production out there in 65/70. RICK: Kodak is having financial problems and since 65mm stock is a special order item, today it would not be worth it to them to offer it at 35mm prices. |

|

| RAMON: I thought it would be a good idea to finish the interview with a

final conclusion from you on what you think the advantages for producers

and exhibitors would be if they produced some films using 65mm negative

with some prints in 70mm. For instance, do you think that a film like

the latest Indiana Jones would fare better at the box office if produced

in 65mm with 70mm prints? RICK: I don't think it would make any difference here the US, though it might in Europe. As I mentioned, the blowups for sound in the Eighties ruined that public's impression of 70mm. It would take something like Bob Weisgerber's DI conversion to 48 fps, resulting in a different and more spectacular image, to make a difference that would affect an audience, but this would require the installation of special projectors. I don't know if it's being released in Imax, another distortion of the idea of 5 perf 70mm, especially since the 2.40 ratio will have to be maintained. RAMON: I agree completely with your opinion on the blow-ups and have expressed it myself on several occasions in the past. I did not mean a blow-up, what I meant is a production filmed in 65mm and distributed in 70mm, at least in major cities, do you think that such a production would bring more audiences to cinemas than a 35mm film shown in 2k? Do you think audiences would notice? RICK: It would depend on the subject of the film and the degree to which it is shot to exploit the quality of the 65/70mm image on a big screen. This was the major problem with Kenneth Branagh's "HAMLET", which was shot like a standard 35mm film of the time, mostly tight closeups with long lenses. His next film, "LOVE'S LABORS LOST", with the same cinematographer and in 35mm anamorphic, actually made better use of wide screen, especially in the musical numbers. I've discussed this with Bob Weisgerber about possible projects for Super Dimension 70, which has the additional need to draw audiences because of its special installation requirements. I think the right film in SDS-70 would draw because it does promise a unique experience, which is no longer applicable to regular 5 perf. In this case, starting in a limited number of theaters and generating word-of-mouth from that would work, I think, but again, it must be the right dramatic film, shot right. Though the guy who made "Baraka" is now doing another documentary [non verbal film, ed] in 65mm, I don't think this will draw the kind of audiences that will revive interest in 70mm. Even 15 years ago, I don't think "BARAKA" got that many 70mm playdates and there are even fewer outlets for the new one. |

|

| RAMON: Why do you think 5 perf is no longer a unique experience? RICK: I don't, but over here the general public has really not seen 5 perf since the Eighties, when it was used for blowups. Today, there needs to be something special and unique about the film just to get them in. Then, hopefully, the word-of-mouth about the superior image quality over both 35mm and HD, and possibly as, if not more, impressive than Imax, will get enough people in to convince the studios that doing more will be viable. But again, it has to be the right film. Definitely not another "Hamlet", nor possibly even a "Far and Away". RAMON: I agree with you about the right film. Can you think of any recent releases that could have been a good option to bring back 65mm production and 70mm prints? RICK: No, because none of today's "bankable" filmmakers know how to shoot for the big wide screen, with the possible exception of Quentin Tarantino and maybe Steven Soderberg, who'd at least understand the ramifications of what he's doing. Unfortunately James Cameron and Robert Rodriguez are now only interested in digital. From a conceptual standpoint, the "LORD OF THE RINGS" and "PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN" films would have been perfect subjects, but not the way they were ultimately shot and edited. |

|

| RAMON: Yes, unfortunately too many filmakers frame films for the small

TV screen instead of the big cinema screen. Also, why do you think Super Dimension 70 has, so far, failed to convince any major studios or exhibitors of the benefits of their product? I would imagine that Kodak would be interested themselves in promoting a film product. RICK: Bob has still not been able to get any studio executives to see it, and for the moment has no place to show SDS-70. I did get a guy from Kodak to see it and he was very impressed and I assume he spread the word to others there, but these things are really out of Kodak's hands. They are not in a position to fund the production of a film in SDS-70. |

|

| RAMON: We could really keep talking and talking and it has been a

pleasure getting to know your thoughts on this most fascinating subject.

I would like to finish this interview/conversation with your thoughts on

what you envisage is the future of cinema exhibition. How do you think

will be the next 50 years of cinema exhibition? Film, digital, big

screens, small screens, stereoscopic cinema, flat cinema or ... mainly

home cinema? RICK: While I don't think cinema exhibition will last another 50 years, I was hopeful about it holding out for another ten years or so until the industry depression of 2005. My view is now quite bleak, for which I blame both production and exhibition, and my reason is in light of what we've been discussing. I don't see continued public support for theatrical moviegoing because it is no longer a unique experience worth the increasing admission costs being charged when they now have an ever increasing number of cheaper alternatives even for the films that were the reason for going to the theater in the past. This won't affect production that much, but will impact exhibition in a world where financial success rules and exhibitors are at the bottom of even the entertainment industry snake pit. Exhibition is the one area of the industry about which most commentators on the subject know little or nothing, but which I have followed since working as a projectionist as a teenager in my neighborhood theater and running across issues of Boxoffice and Motion Picture Herald which the theater apparently got for free and which nobody there ever read but me. Between that and occasional conversations with the manager, I got some idea of what it was like to run a movie theater and have had some relatable experiences running college film programs in the Sixties and Seventies, as well as having had discussions about distribution with friends who are in the end of the business over the last decade. What most people, especially critics, don't realize, is that an exhibitor has to make at least his weekly "nut" to stay in business. That's his film rental, salaries, and other operating expenses. That means he has to get as many people as possible in every week by having something on his screen that they want to see every week. Depending on the type of theater, first or sub-run, and its location, he may be able to hold a popular film two, even four weeks, but if only a small number of people have come by the first Sunday evening, he'd better have a replacement ready by the next Friday. And if the theater is a multiplex, he needs to have something new on at least one screen every week. This situation has existed since the Nickelodeon 100 years ago and kept moviegoing alive in the United States until 1947, when the attendance decline began and continues to this day. Contrary to historic generalizations, this was not initially due to television. John Belton, in Widescreen Cinema, was the first to point out that this was because for the first time in over 15 years, Americans had other things to do with their time. What he and others have overlooked is that the decline was exclusively with 25-50 year olds, the people who'd either fought World War II or had put a lot of time in defense work. 15-24 year olds continued to go, as did over 50s who'd gotten into the regular moviegoing habit. One other point that has not gotten the attention it should: the theatrical industry has survived, and to a degree continues to, because it was the cheapest form of non-athletic entertainment available outside the home. And its continued appeal since the wide dissemination of tv in the mid-Fifties has been to those segments of the populace with fixed or limited incomes who like to do something affordable outside their homes once a week or so. These are young pre-child adults just starting their careers, childless middle aged couples and singles, and older retired people. Yet though I've never seen it officially acknowledged anywhere, my own research reflects the point that prior to the mid-Eighties, most Americans saw movies in neighborhood and grindhouses and drive-ins rather than in first run movie palaces. In recent years however, the focus has been placed on theatrical first run with most of those cheaper places switching to first run at current prices or closing; only a handful remain as "bargain" houses. In 2005, the biggest complaint made by over 30 members of the general public as to why they don't go to the movies regularly is that they felt it cost to much! This doesn't seem to impact 15-24 year olds, who have more disposable income, but does affect those on limited incomes who'd like to see films on the big screen in a theater environment even if they are able to afford high end home theaters and can fit them into their apartments. These are people who have grown up with the theatrical moviegoing habit. One point that was brought out in the 2005 discussions is that we are now developing a generation of kids who have not developed that habit, especially young men, who used to go to movies with their buddies when they didn't have dates. Now, they are increasingly picking and choosing what they're willing to see in a theater and what they'll wait to see on video. Some even prefer small screens to the big theater experience. Most of them apparently can afford to go to one or more film every weekend now, but once life kicks in... Based on my study of the past 60 years, I think 3-D, Digital Cinema and other technologies will only be temporary solutions because they won't get enough people into theaters on a regular basis frequently enough to cover the costs of their operation, and once some studio releases a high profile $200+ film on video concurrent with theatrical release and makes back that cost in one night, it's over for theaters as far as the production-distribution companies are concerned, as they are now part of conglomerates who could care less about the traditional release pattern if it is no longer profitable. No one seems to have noticed that the theatrical presentation of motion pictures is actually an anomaly in terms technical entertainment inventions. All others since the dawn of the 19th Century were for use in the home; in fact that was Edison's intent in having Dickson develop a visual compliment for his phonograph. It's fortunate that the theatrical film became enough of a part of the life of 20th Century Americans and others to survive as long as it did. RAMON: Dear Rick, thank you very much for your time and for sharing your expert knowledge with the workshop. Let’s hope that the future will bring some return of the showmanship of years gone. |

|

| Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|