Time Traveling to the New Neon |

This article first appeared in |

| Written by: Mr. David Joachim. Pictures by: Thomas Hauerslev | Issue 53 - June 1998 |

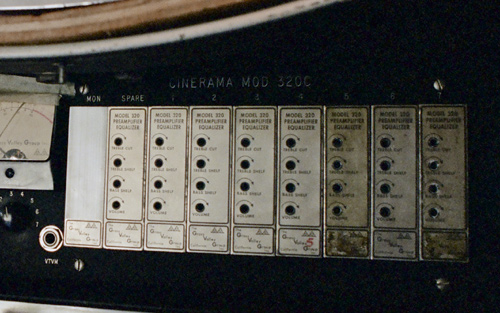

John

Harvey rewinding Cinerama film John

Harvey rewinding Cinerama filmIt isn't replete with brilliant lights; its slate gray and beige colors are drab and uninviting; its rounded triangular shape makes it almost like a homely-looking spaceship. It's nothing like the monstrous UFO that beckoned people the world over to an odd American outpost in "Close Encounters of the Third Kind", but the New Neon Movies does resemble some sort of otherworldly vehicle that has crash-landed in the unlikeliest part of an unlikely cinematic Mecca. It has blended in with a pair of anachronistic diners nearby and hidden behind an enormous parking garage, apparently escaping detection from many of the locals. Earthlings fortunate enough to share the psychic message urging them to convene in Dayton, Ohio were luckier than those in Steven Spielberg's 1977 sci-fi classic: government intervention prevented most of Spielberg's characters from realizing their dream of bridging the space/time continuum. The New Neon's travelers have numbered in the thousands and come from more than a dozen countries and most of the United States. Since August of 1996, they have been allowed to board the 212 seat spaceliner for weekend excursions back in time. I bought my first class tickets in April of '97 and booked passage for a three day trip. My fellow travelers came from America's East and West coasts, as well as parts of Europe. We shared a common bond: an undying love of the world's greatest widescreen process, Cinerama. In the years B.C. (before Cinerama), screen dimensions and stereo sound meant nothing to me. Many of the theaters I frequented as a youngster paid little or no attention to proper masking and projection, and sound was always monaural. I didn't understand the concept of the wide screen until I took a field trip to New Orleans' Martin Cinerama theater and saw "How the West Was Won" as a teen-ager. It was an assault on the senses that would forever change the way I would judge film technology. Cinerama's power was too great to ignore and forget. I pined for its return, a return that wouldn't occur for over three decades. |

Further in 70mm reading: |

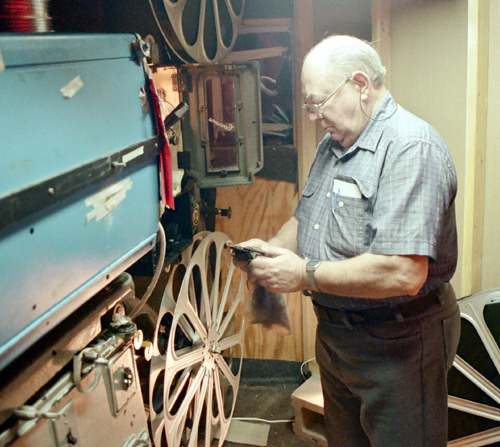

John

Harvey original Cinerama equipment. John

Harvey original Cinerama equipment.No one in the universe could have been more impressed by Cinerama than John Harvey. As a youngster, he began hanging around projection booths, absorbing technical information from veteran projectionists. Watching "This is Cinerama" at a Cincinnati theater when he was 17 galvanized his desire to become a projectionist. He was eventually trained by Cinerama and projected films in the process during its heyday. As Cinerama theaters began going dark in the seventies, John began acquiring various discarded prints and projection equipment. He developed his own method of showing the films in his home, using a series of mechanical shafts and timing belts to synchronize the machines. He eventually converted a significant portion of his home into a personal Cinerama theater, complete with recessed lighting, motorized curtains and original selsyn-interlocked projectors. He even has his own popcorn machine and napkins with the Cinerama logo on them. When Larry Smith, the New Neon's manager, convinced John that his modest theater could be modified to show the films to admiring fans, Cinerama enjoyed a revival whose success few could have predicted. The sporadic publicity it enjoyed (mostly in trade magazines) served to energize its fans, who used word-of-mouth to help sustain the project. After negotiating rental details with the films' copyright holders, Smith and Harvey converted the theater in less than a month. 88 of the theater's 300 seats were removed to accommodate the three projectors and curved screen. And what was supposed to be an oddball, two month experiment designed to keep the New Neon from being converted into a twin cinema, has evolved into a remarkable run with an international cult following. |

|

"How

The West Was Won" in 3-panel Cinerama. Copyright Cinerama Inc. "How

The West Was Won" in 3-panel Cinerama. Copyright Cinerama Inc.The New Neon's success resembles a surprising off-Broadway hit, with a one man cast and an untested understudy. (Larry Smith has tried to absorb some of John's considerable knowledge of how properly to present the films should the projectionist fall ill, but is grateful he has never had to fill in for him. The gratitude shown by Cinerama fans from across the globe seems to energize the sixty year old projectionist, and seems to immunize him from illness and fatigue.) John has perfected a system that enables him to automate much of the process that once required over a dozen technicians. He moves from machine to machine, constantly making subtle adjustments and corrections that go undetected. He resembles a circus performer who keeps plates spinning tenuously on thin, wobbly sticks. Film buffs are drawn to Dayton to see Cinerama offered by film exhibition's greatest performance artist. The New Neon's 18-by-48 foot curved screen is modest by Cinerama standards, although perfectly proportioned for the 90 by 90 foot auditorium. There are no bad views from the 120 seat center "sweet spot." Harvey has paid homage to the magnificent Technicolor IB prints by slavishly preserving them and keeping them remarkably free of scratches and dirt. |

|

Gunther

Jung preparing a Cinerama

film Gunther

Jung preparing a Cinerama

film"How the West Was Won" looks practically as good now as it did when I saw it in 1963. I expected "This is Cinerama" to suffer significantly from the ravages of time, but its Technicolor hues are also intact (even if more than a few of its weathered frames have had to be replaced by spacer [a.k.a. slugs in Hollywood, ed]). "Cinerama Holiday", the second film produced in the process, is the most cinematic and dazzling of the three features I got to see. Yellows and greens make cameo appearances in a few scenes, but the starring color is pink -this is an Eastman print that has faded in the intervening four decades. The now mono-chromatic classic features ambitious skiing and bobsledding sequences that required cleverly improvised rigging, but it doesn't rely solely on dizzying moving shots. It also uses the enormous aspect ratio to present events as diverse as a fashion show and a re-enactment of a jazz funeral. Veteran Cinerama technicians recall the alignment problems that dogged them when they shot the various travelogues. "Cinerama Holiday" has an infamous shot where a woman standing too close to one of the frame junctures appears to have three legs. I never saw that shot in the film; apparently John deftly adjusted the projection mask and hid the flaw. He knows where all of the flaws in his prints are--he's seen them thousands of times. When Hollywood finally acknowledged Cinerama's superiority as a widescreen process, they attempted to mold it to fit their way of making films. "How The West Was Won" endures as a classic despite MGM's attempts to circumvent the complicated filming process. Entirely too much of the film relies on process shots filmed in 65mm. As a teen-ager I didn't notice the annoying graininess that's now all too apparent. The famous buffalo stampede is the only sequence that seems to hold up, despite its reliance on Ultra Panavision. The dust the beasts stir up as they storm the railroad camp hides much of the grain of some of the 65mm clips. |

|

Beatrice

Troller, John Marsh, Betty Marsh York and Fred Troller. Beatrice

Troller, John Marsh, Betty Marsh York and Fred Troller. What really stands the test of time is the sound. John Harvey beams when he points out that the president of IMAX admitted he preferred Cinerama's sound to IMAX sound. The IMAX chief confessed to the preservationist that he should have listened to Hazard Reeves, Cinerama's sound designer, when IMAX was being developed. He appreciates Cinerama's wide dynamic range and true stereophonic effect, an effect that relies more on proper microphone placement than it does on a postproduction engineer's idea of how sound should be positioned after the fact. John Harvey wishes Hollywood would acknowledge that they were wrong to run from Cinerama's demanding technology. He wonders what might have evolved if they hadn't worked so hard to develop easier widescreen processes. The same ingenuity that spawned digital sound, Wescam aerial photography and computer-generated special effects, could have been used to refine Cinerama and make it more practical. Now Smith and Harvey have formed the Cinerama Preservation Society, a not-for-profit organization designed to preserve the rare three strip process. John Harvey keeps increasing his inventory of Cinerama films, and the pair hopes to ultimately build a museum dedicated to other lost widescreen formats. America's Library of Congress has honored their efforts (as well as England's Museum of Photography, Film and Television), by putting "How The West Was Won" on its preservation list. The LOC will try and coax a new print of the film from Ted Turner, its copyright owner. During my visit to Ohio, I took in an evening showing of Kenneth Branagh's "Hamlet". English literature's greatest work, presented in 70mm, drawing a near-capacity crowd of Daytonians, some of whom were obviously sitting in the New Neon's cushioned, crimson seats for the first time. I watched them crane their necks as they surveyed the auditorium, staring at John's makeshift projection booths and curved, louvered screen. When a few of the patrons began making inquiries about the odd setup, I tried to explain what Cinerama was. They struggled to grasp the concept, but I couldn't help but feel they didn't really get it. I couldn't fight the feeling that more than a few of them thought I had just landed in an alien spaceship. |

|

| Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 22-01-25 |