Remembering Miklós Rózsa |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Jeffrey Dane, USA | Date: 1. May 2007 |

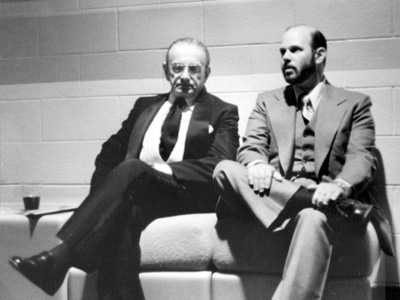

The author with the composer in New York, Oct. 1978, after a screening of

"Ben-Hur" and "King of Kings". The author with the composer in New York, Oct. 1978, after a screening of

"Ben-Hur" and "King of Kings". As a young teenager studying music, I thought of how fulfilling it would be to compose serious music for films. Aside from an early but very earnest and successful effort in composing the music for a friend's film, the closest I ever got to the initial hope was operatively the next best thing: I was privileged to get to know one of the truly great composers who worked and spent most of his career in Hollywood. The music he composed, for whatever purpose and venue, within or without the studio, was better than anything I could ever have written, so I have no regrets. In his memoirs, Miklós Rózsa relates how a young man once told him that as a boy he had been ". . . sufficiently moved by the music [for "King of Kings"] to familiarize himself with the same events as recounted by Bach in the Passions." I had unwittingly followed that example: finding that Rózsa's film music made an eloquent appeal to my musical sensitivities, I ultimately extended my search from his movie scores to his concert and chamber works. . . I was soon pursuing his absolute music with even more verve than his film scores. . . |

More

in 70mm reading: A Visit With Miklós Rózsa Remembering Dimitri Tiomkin New recording of Tiomkin's ALAMO score Internet link: Publisher iUniverse Lincoln Nebraska USA www.iUniverse.com The contact is Mr. Dan Silvia American Composers |

A letter from the composer, in which he makes mention of

"Ben-Hur". A letter from the composer, in which he makes mention of

"Ben-Hur".Click image to see enlargement It's been said that in Hollywood "you're only as good as your most recent success." Unfortunately it's often a common guideline for the shallow. The view Miklós Rózsa took of others he recognized as earnest, sensible, intelligent people was that you're always as good as the best thing you've ever done. Indeed, earnest, sensible and intelligent people will recognize the contrast. I was lucky enough to attend the New York premiéres of "King of Kings" in 1961, and then of "El Cid". My primary target was to meet the composer. At the former, I asked director Nicholas Ray if Miklós Rózsa was there that night, and he replied that he was in Spain working on the score for "El Cid". At the premiére of "El Cid" not long afterward, I asked producer Samuel Bronston if the composer was present that evening. "No, I believe Dr. Rózsa is in London working on the score for "The VIPs"." Patience can have its own reward -- but it should be coupled with perseverance. |

May 3, 2007 Thomas - Thank you for posting on your website the info and material I sent you about my book on Miklos Rozsa. You have made an extremely handsome presentation of it, I must say. I am headquartered in New York City. -- And on your next visit here, I would be pleased to have the pleasure of personally making your acquaintance. Yours again with thanks, Jeffrey |

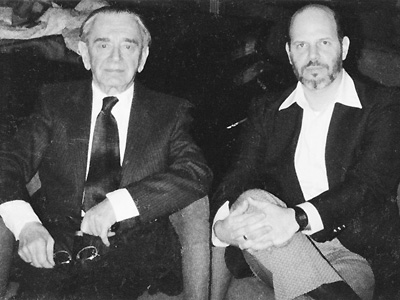

The author with Dr. Miklos Rozsa in Hamilton, Ontario (Canada), Oct.

1977, after the composer conducted a concert of his own works. The author with Dr. Miklos Rozsa in Hamilton, Ontario (Canada), Oct.

1977, after the composer conducted a concert of his own works. I wrote to Miklós Rózsa for the first time late in 1967. I included manuscript paper on which I had notated the cello part in the "Farewell To Rome" sequence from the album More Music From Ben-Hur, conducted -- according to the album's credits -- by Erich Kloss, though Rózsa enthusiasts now know better. (The first recording of music from the film, an MGM deluxe soundtrack album on which Carlo Savina conducted, didn't include this "Farewell To Rome" sequence). On the staff above the cello part, I notated in red pencil the recording's prominent violin solo, and I included the harmonies on the two lower staves. I told Dr. Rózsa in my letter that I didn't recall having heard the violin solo in the film itself. The first meeting. -- In the spring of 1972 I'd heard about the imminent formation of an organization to be called The Miklós Rózsa Society. After some inquiries, in early June I phoned the founder to ask for details about the fledgling entity. I soon became a Charter Member of the Society. |

|

The author with the composer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania USA in May,

1984, on the occasion of the world premiére performances of the composer's

Concerto for Viola & Orchestra. The author with the composer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania USA in May,

1984, on the occasion of the world premiére performances of the composer's

Concerto for Viola & Orchestra.During our chat he mentioned in passing that Dr. Rózsa himself was in New York City enroute to Italy, and that they'd be meeting for lunch on Saturday. I said something to the effect that, ". . . I imagine Dr. Rózsa is staying at a place like the Waldorf-Astoria," but I was told he was actually at the Hotel Algonquin. The Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained principle applied here. . . I prepared a telegram to send to Dr. Rózsa at his hotel, in which I told him it was nice to know he was now nearby, and that the new Society's director would be very fortunate in having lunch with him on Saturday. As a courtesy I ended my telegram with a phrase in Hungarian: Leg szívesseb és szerenczés jövöt kivánok (meaning, idiomatically translated, With every good wish and with sincerest respect). In response to my telegram to the composer, I expected nothing -- but we all have the right to hope. In mid-afternoon on Thursday, June 8 [1972], my phone rang. The composer was calling. "This is Mr. Rózsa," he said. It was only later on I learned why he so introduced himself: it seems he'd caused some undue concern on a few occasions with those he didn't know, when he had identified himself on the telephone as Dr. Rózsa. On this fine June day, made the finer by his phone call, he thanked me for my "very sweet telegram," we exchanged some pleasantries -- and he invited me to join him for lunch on Saturday at the Russian Tea Room, adjacent to Carnegie Hall, at 12:30pm. He also added, "Please tell [the Society's director] that he may also invite as many members of the Society as he wishes." |

Just some

of the myriad films for which Miklos Rozsa composed the music are: · Knight Without Armour ( - his first film score) · The Four Feathers · The Thief of Bagdad · Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book · Sahara · Double Indemnity · Blood on the Sun · The Lost Weekend · Spellbound (Academy Award) · The Killers · The Red House · Brute Force · A Double Life (Academy Award) · The Naked City · Madame Bovary · The Asphalt Jungle · Quo Vadis · Ivanhoe · Plymouth Adventure · Julius Caesar · Young Bess · Knights of the Round Table · Men of the Fighting Lady · Valley of the Kings · Green Fire · Moonfleet · Diane · Tribute to a Bad Man · Bhowani Junction · Lust for Life · Something of Value · A Time to Love and a Time to Die · The World, the Flesh, and the Devil · Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (Academy Award) · King Of Kings · El Cid |

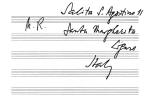

The composer's address in Italy, written in his own letter-hand on the

day the author first met him. The composer's address in Italy, written in his own letter-hand on the

day the author first met him.Click image to see enlargement The composer and five of his admirers spent about three hours at that luncheon, during which I gave him a copy of my first published article, "The Significance of Film Music", which had appeared in the May, 1961 issue of American Cinematographer Magazine. I also offered him a sheet of staff paper and asked him if he'd be kind enough simply to jot down his address in Italy so that I might write to him. Among the countless questions asked of him by all of us on this day, one from me was whether or not he had a special, personal preference for a particular abstract work of his, and for any one of his film scores. Without hesitation, he replied, ""My Piano Sonata", and "The Lost Weekend"." "There was no-one in Hollywood whose acquaintance I more earnestly desired to make than Aldous Huxley . . . When I met [Richard] Strauss, I was almost speechless with admiration." This is what Dr. Rózsa said in his memoirs. I can best voice my own sentiment about him by paraphrasing the ideal way he had verbalized his feelings. There was no-one in Hollywood whose acquaintance I more earnestly desired to make than Miklós Rózsa. And when I finally met him -- at 12:30pm on Saturday, June 10th, 1972, after thirteen years of trying -- I felt almost speechless with admiration. I had no way of knowing I'd eventually get to know him as I did, and that he'd ultimately call me his friend. |

· Sodom and Gomorrah · The V.I.P.s · The Power · The Green Berets · The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes · The Golden Voyage of Sinbad · Providence · The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover · Fedora · Last Embrace · Time After Time · Eye of the Needle · Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid ( - his last film score) |

Extract 1 - Remembering Miklós Rózsa |

Table of Contents |

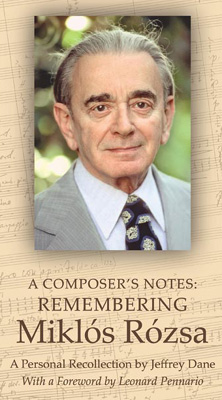

Cover of

book Cover of

book. . . With his music for "Ben-Hur" (MGM, 1959), Rózsa created a veritable classic in film scores. The opening passages are vital to the film's atmosphere. They're responsible in large measure for creating the mood of the entire feature (three hours and 28 minutes long in its original-release form), and they make the viewer aware they're about to experience something significant. The prologue, a filmic depiction of the Adoration of the Magi, concludes with the sound of a shepherd's horn as the Star of Bethlehem fades into the night sky and disappears. A sudden strong but gradual build-up is heard from the brass and then briefly sustained on a chord as "A Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Production" appears on the screen in gold Roman lettering. As the music continues a harmonic ascent with a crescendo of brass fanfare, a cymbal crash and final chord of the opening motif is heard, and the main title "Ben-Hur" appears on the screen against a magnificent backdrop of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel fresco, The Creation of Adam. The music is dramatic and inspiring and carries the viewer through the film's entire prelude, supports the remaining opening credits, and quietly modulates into the movie's first scene. Rarely has so much stirring and descriptive musical material been poured into a mere introduction to a film. To evoke so much feeling in such a relatively short passage of time has its own intrinsic difficulties, but Rózsa succeeded with "Ben-Hur" and the results of his efforts on this score earned him his third Academy Award. "The single best performance I've seen in any movie" is how filmologist Don Miller described Frank Faylen's minor role but memorable portrayal of the sadistic male nurse in the film, The Lost Weekend. One can comfortably and suitably clothe his remark in musical garb: "Ben-Hur"'s "Magi" sequence is graced with what may be the most touchingly moving "Nativity" music heard in any film. Since our reactions are by nature personal we can speak only for ourselves, not for others, but that passage in the film gives new meaning to the concept of inspiring and affectingly beautiful music, even without the visuals. Rózsa himself felt Bach would approve, and it seems he pulled out all the stops for this music. Rózsa had chutzpah, the slang Yiddish word for audacity: he also pulled the wool over the studio's eyes, thereby discrediting his "superiors" by implication, when he suggested composing music of his own, rather than complying with the idiotic request to use the anacronistic Adeste Fideles (O Come, All Ye Faithful). The studio disregarded that notion when Rózsa threatened to leave the picture, and that his own music in fact postdates the medieval Latin hymn seemed to escape the attention of those "in charge." Christ's birth was an event which in retrospect was ultimately unique in the world's history. The historical consequences of what happened then are now a matter of historical record. No-one like the rabbi from Nazareth had ever lived before, and music accompanying a cinematic representation of the advent of that occurrence should be unique as well, in keeping with the singularity -- and the ultimate extent -- of the circumstances. Rózsa had the right idea, it would appear. The general paradoxes of the film colony extend even to musical matters in particular. By various legal strictures and other problems, at the time of the film's release the commercial record albums of the score had to be conducted by others, rather than the composer himself, and that by a strange set of logistical difficulties it wasn't until only 1996 that a commercial recording (on the Rhino label) of the original "Ben-Hur" stereo music tracks, conducted in the film by Rózsa himself, was made available to the public -- nearly four decades late but certainly none the worse for it. |

Acknowledgements Author’s Preface and Notes Foreword Introduction Film Music: Observations and Comments A Note On The Correspondence Notes and Letters, 1968 – 1978 Photographs Notes and Letters, 1979 – 1983 Facsimiles Notes and Letters, 1984 – 1988 Pittsburgh Chronicle – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania - Prelude - Thursday, May 3rd - A Conversation With Miklós Rózsa - Thursday Evening - Friday Morning Rehearsal - Friday Evening - Concert Time: The Sound of Music - Saturday Morning - Saturday Afternoon - Saturday Evening Performance - A Post-Concert Gathering - Coda - Sunday Afternoon - Epilogue Two Rózsa colleagues: Franz Waxman Elmer Bernstein A Visit With Miklós Rózsa – Los Angeles, California A Memorial Tribute |

Extract 2- Remembering Miklós Rózsa |

|

The first letter the author received from the composer, regarding a

portion of the "Ben-Hur" score. The first letter the author received from the composer, regarding a

portion of the "Ben-Hur" score.Click image to see enlargement . . . The Hamilton [Ontario, Canada] performances provided some interesting episodes. The concerts on two successive evenings gave us two successive incidents that point up just how human all of us can be. -- At the first concert, the composer's tempo in conducting the "Rowing of the Galley Slaves" from "Ben-Hur" was conspicuously faster than what most of us were accustomed to hearing on recordings. Additionally, at the end of the piece, the tympanist mis-counted and thusly added two extra drum strokes -- giving an embarrassingly conspicuous seventh beat to the six-beat phrase that ends the sequence. Those two extra blows on the tympani came at the worst possible moment, since they happened during a short but totally silent orchestral "hold" (fermata) right before the final bar. I was seated very near the stage and to the left of the conductor's podium, and I could see Dr. Rózsa shoot a glance at the hapless drummer at that point. As he put down his baton to turn around and acknowledge the enthusiastic applause, he glared once again for an instant at the poor tympanist. |

|

The last page of the composer's manuscript score of his Concerto for

Viola & Orchestra, on which he notes the specific date and place of the work's completion. The last page of the composer's manuscript score of his Concerto for

Viola & Orchestra, on which he notes the specific date and place of the work's completion.Click image to see enlargement Also played at these concerts was the Parade of the Charioteers from "Ben-Hur". At the first night's performance, even the composer himself missed a cue, anticipating only one bar where two had been written. Luckily this, too, happened near the very end of the piece; Dr. Rózsa's recovery time was as immediate as Leonard Bernstein's was legendary, and the entire orchestra ended together. When the Galley Slaves sequence's faster tempo was mentioned to the composer at a post-concert reception on the first night, his reply was something to the effect that, "We'll see what happens tomorrow." One can easily imagine a wink in the composer's voice. Needless to say, the next evening's performance of that piece was noticeably slower and more deliberate, and closer in tempo to what was heard in the film itself -- and there were also no further miscalculations, from either the conductor, or drums and battery. |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|