An Interview with

Ron Fricke | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

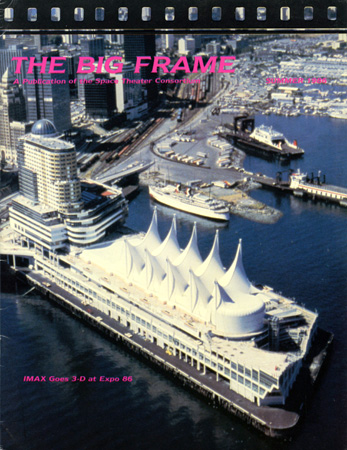

| Written by: The Big Frame, 1986. Reprinted with written permission from Kelly Germain, Giant Screen Cinema Association | Date: 21.08.2011 |

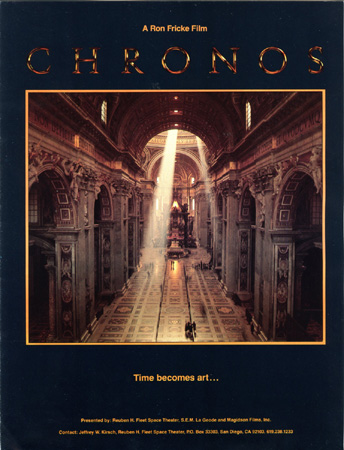

What was your first encounter with the IMAX/OMNIMAX film format? What was your first encounter with the IMAX/OMNIMAX film format?It was like a Close Encounter of the Third Kind. It was in Washington, at the National Air and Space Museum when it first opened. I was there working on "Koyaanisqatsi" as a matter of fact. We were location scouting the Air and Space Museum. I hadn't really even heard that much about this format. So I saw "To Fly" and it was like a close encounter. I just couldn't believe the clarity, the concept of the film, a format that big, and that someone had actually done it. I never, ever got that out of my head once I saw the size of the image, the fidelity, and the fact that it was really a visual presentation. When you say "visual presentation" what do you mean? Well, it's like the word "IMAX." It's just a maximum image system where it's geared for a fidelity image; where the concept of the theater, the construction of the theater, and the optics of the theater are all geared for high fidelity results. This excited you Because you saw this as a mode of expression? Yes. At the time I was working on "Koyaanisqatsi". I was immersed in doing this total visual language film without narration or even central characters. Working in the 35mm format, I was feeling that there was something lacking. Once I saw the IMAX theater and saw the film, I realized this is how it should be done, especially for a non-verbal film. It sets you up in a real atmosphere. Was the highly acclaimed film "Koyaanisqatsi" a model for your first OMNIMAX film "Chronos"? I think that whatever you do, you bring in your experience from whatever you've done. Certainly in doing "Chronos" there would be a lot of influence from "Koyaanisqatsi". Many techniques from "Koyaanisqatsi" would be employed in "Chronos" and taken to another step, really. Especially the time-lapse and motion control techniques. I was just discovering them in "Koyaanisqatsi". And having then just discovered IMAX at the same time it was like putting two and two together. 1 said to myself, "My God, you should do a non-verbal film in a format that is tailored to it." Put all of the money into the equipment to get the images going so that you have a real powerful way of expressing yourself visually with the format. So, I would say that one led to the other. | More in 70mm reading: Ron Fricke 70mm film maker Sacred Site / Night of the Comet "Baraka" cast and credits "Samsara" to Premiere in Canada, September 11, 2011 A Conversation with Mark Magidson and Ron Fricke Internet link: Magidson Film: "Samsara", "Baraka" and "Chronos" giantscreencinema.com GSCA and "Chronos" |

"It's almost a Zen-like approach to film-making." | |

|

As a starting off point as opposed to a model, per se? Yes. You could say "Chronos" was an experiment in that direction. It was to develop the time-lapse techniques into another area. Not blooming flowers and rolling clouds, but taking it into areas where it hadn't been applied in live-action motion control. It's so subtle you really haven't any idea that it was shot in time-lapse. Yet it is revealing something unfamiliar about very familiar things. I am more drawn and interested in showing things that aren't visible. I know that sounds a little silly but you experience something when you see a normal state altered. You feel something different about something normal, and I like that. I think it's expanding and it makes you think about who you are and where you live in a different way. It's not documentary filmmaking. It's approached that way but the feeling you get from it is not what you would feel in a normal documentary. It's more experiential. | |

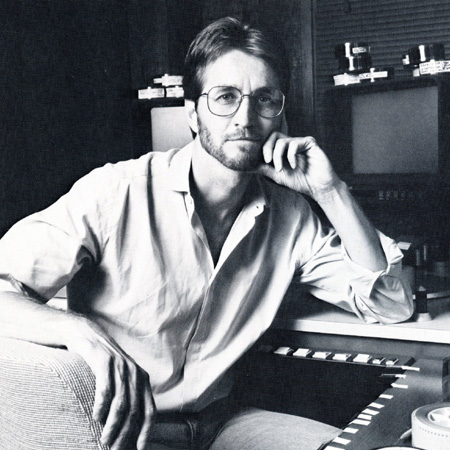

Ron Fricke at his editing console in the Canticle Films studio, Culver

City, California. Ron Fricke at his editing console in the Canticle Films studio, Culver

City, California.What are the major differences between the design and photography of a film in standard 35mm and in IMAX/OMNIMAX? The whole visual thinking is altered. You could say it's like shooting with an 8 x 10 plate camera as opposed to shooting with a 35mm still camera. It's really that different. The frame is not that fluid or as loose as it is in 35mm or 16mm where you can just pick the camera up and shoot hand-held stuff. In 35mm, you're used to moving the camera around a little bit. You can be rough with it and your glitches don't show up as much. But in IMAX, everything is amplified. Every little jerk, bump, and imperfection in the lens, exposure, lab, and everything down the line has a cascading effect. It's just so technical. In shooting, it gives you a whole different visual sense because you're shooting an image or a frame that's atmospheric. You're shooting something that gives a lot of information in a scene. It's not a close-up medium, but close-ups can be done. You really have to balance your composition so they're quick and easy to read, not confusing or causing you to break your neck to figure out what's going on in the shot. It's almost a Zen-like approach to filmmaking. You have to be real quiet for this stuff. It's big and a little bit awkward, and you have to be so delicate when you shoot with it that it's almost like a Zen state you go into when you finally roll that camera. You hold your breath because it's penetrating in a way that you can't penetrate in normal cinema. Do you consider yourself a perfectionist? I don't know. I know I drive myself nuts sometimes trying to control everything when, really, things are under their own control. I certainly have my ideal about how everything ought to be. When does a shot come to you? You can work a lot of things out on paper but it gets down to this. When you get to a location, it depends on how you feel, when you ate, what time of day it is, what kind of access and permits you have. You actually look out there at the real world and you look with this IMAX/OMNIMAX eyeball, you see just what you can photograph. With IMAX some things will and some things won't. And then and there you see it. On "Chronos" that was my main objective. I went after what I thought would photograph most dynamically in the IMAX/OMNIMAX format. I just excluded everything else immediately and went just for what I thought would compose and scale correctly to that system. The wide shots would balance and draw you into the system, into the frame. Close-ups were handled like details that were very easy to read, almost like landscapes. | |

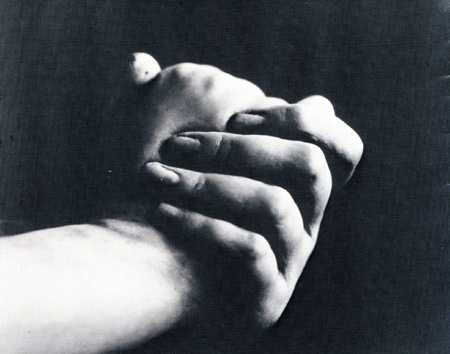

"In "Chronos", close-ups were handled like details that were very easy to

read, almost like landscapes." (Detail from a sculpture in Notre Dame de

Paris.) "In "Chronos", close-ups were handled like details that were very easy to

read, almost like landscapes." (Detail from a sculpture in Notre Dame de

Paris.)For CHRONOS, you filmed in eight countries and dozens of locations. Which provided the most challenge and reward? Well, that's a hard question to answer. I think the most rewarding were the interiors. I thought about the interiors as shooting a light moving around in a room but not really visualizing the effect that it would have on the screen, of being in an interior that had not been lit, but only illuminated with natural light. The effect was something as if you were outdoors. It gave you a whole different sense of an interior and that was something I didn't expect or really didn't pre-visualize. It fit well. Especially the Vatican, the tilt inside St. Peter's, I think, is my favorite shot in the film. It was probably the scariest to shoot because we were working under a certain time structure. We didn't know if we were going to get the permit, and then suddenly we were allowed to be on the Pope's balcony, under armed guards. We were setting up the equipment and I didn't know if there were clouds outside or not. Most of the time I wanted clouds because I wanted some movement but when you're indoors you don't want any clouds because you want the light to come in. And then suddenly, it all happened like magic. These light beams appeared and I just kept praying that the camera would keep running. We were working with a prototype camera that was doing five second exposures per frame and tilting at the same time, and all of these systems were operating with motion control. Everything was beeping and all of these Italian guards were looking at us. It took us over two hours to do that take and it was like splitting hairs. It was a one-take shot. You don't get to shoot it a couple of times. A lot of elements have to fall into place and luck has a lot to do with it. | |

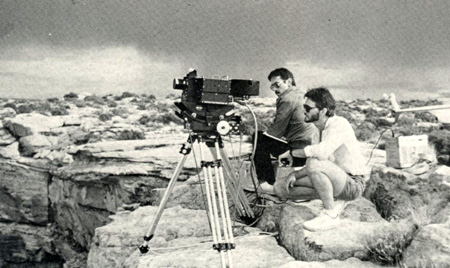

"Chronos" location shoot with Wayne McGee at Lake Powell. "Chronos" location shoot with Wayne McGee at Lake Powell.Which shots in "Chronos" turned out to be less than expected? What didn't come out so well were the aerials. There was a lot of shake. It was very disappointing because of the amount of work we did to get them. We built the mount and then we rented the Williamson W4 camera on a special arrangement. Because our budget was so low, we had access to it only at certain times. Again, we were up against all those elements of weather. At the actual times we did fly it wasn't that turbulent and I was able to get images that I thought composed really well. But unknowingly, the lens was shaking in the lens mount and that caused a vibration. It really made me feel a little sick after I saw those images. So you've really got to double-check your equipment before your go out and that's one thing we did not check. You have just returned from location at flyers Rock in Central Australia to film the southern night sky and the April 1986 apparition of Comet Halley. What was your reaction? Well, when I walked out to the International Halley Watch Site and looked up, I said, "What is this, clouds?" The astronomers said that it wasn't clouds, it was the Milky Way, as if to say, "Where have you been?" 1 thought it was cloudy, honestly! It was very brilliant and bright and I could tell we were going to get excellent results right then because I had not seen anything like that in the Northern Hemisphere. Even from the top of Haleakala in Hawaii there were very bright stars against a very black sky, but the Milky Way was not very bright. But in Australia, out at Ayers Rock right in the middle of the Outback, in the land of the Aboriginals, there is a whole different sky. Very brilliant. It was an amazing feeling just to look up at it. Did you have to become an astronomer to shoot this film? No. Actually I don't know that much about astronomy but I had enough expert help around me at the Halley Watch Site. There is a quite funny story about when we first arrived with all of our cases of equipment. They thought, my God, what have you got in these cases? So when we dragged out our equatorial mount, which is a pretty big mount to hold this IMAX camera, they were looking at us like we were authorities on astronomy and they started asking us questions. I had to tell them, "Look, I don't know anything about astronomy." And they said, "You have all this equipment and you don't know anything about astronomy?" I said, "Look, I'm a filmmaker. Now all I know is to put the camera on the mount and it's supposed to track. But I need you to set up the mount so that it does track." And that's what they did. They did the alignment which took about a day and a night. Essentially, the equatorial mount is a mount that a telescope goes on. What we did is take the telescope off and mount the camera so it will track with the earth's rotation. That way the stars won't streak. How would you describe the major location for the shoot? Were you at one spot? Yes. The astronomers told me you would see the same sky no matter where you went so 1 felt we should go to one spot. The spot we picked was Ayers Rock and that was based on the weather report. It had the least cloud cover. The weather satellite picture on television in Australia was always clear with clouds along the coast. I think we made the right decision even though it was dusty. Out of 12 nights of shooting, we had 11 clear nights. | |

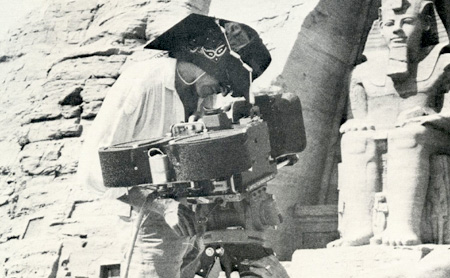

"Chronos" location with Ramses II in Egypt. "Chronos" location with Ramses II in Egypt.Your objective was to get enough material for a three-minute short film, but did you have a definite scenario? Not really. We were just going to go down there to photograph the comet and the night sky. Also, we stayed in Australia for nearly four weeks in order to shoot the lunar eclipse. The comet window was around the 8th through the 15th of April. The lunar eclipse was on the 24th. Only then, the night of the lunar eclipse, did I see the film flash in front of me. Actually, what had happened was that the full moon was in the sky, washing out everything in the night sky except the bright stars. Slowly the moon began to disappear and when it became fully eclipsed, there was the entire night sky and Milky Way in all of its brilliance! It was like a super window that allowed you to see the comet. As the moon began to eclipse back, it disappeared. It was then that the idea was born for a structure for the film. We would start the film on a sunset into a moonrise, then the moon would rise, the moon would eclipse, you would go into the Milky Way, the comet, back to the moon, then it would eclipse itself back and set. Do you have a title yet? We're working with "Night Fires" because in the Aboriginals' mythology, the stars were thought to be the campfires of those living in the sky world. This is very fitting because the mythology is alive and well in their culture and they are very much alive and well in the Australian desert. We had an Aboriginal guide. His name was Dickie. We would drive down the road, get out, and he would wander around and say, "Well, you can film in this area but don't go on this side of the road or don't go any closer to the Rock here." And we would ask why and he said that there was a man sleeping there. And this goes back into his mythology. A certain part of the Rock was called the "kangaroo tail" and under the kangaroo tail is a man sleeping and you don't want to disturb him. The Park Service and rangers would do exactly what this Aboriginal elder said. Therefore, it restricted us as to what we would shoot. But as we became friendly with Dickie, he let us get closer and closer. What subjects are you thinking of for future IMAX/OMNIMAX projects? I really like the idea of nonverbal films in this format and films that are more upbeat and fun, and dealing with really good music. Gershwin is an example, also big band swing music, classical music, and Beethoven. I would love to take the Ninth Symphony and do a piece on that. | |

Are you going to extract something from the music to develop a theme? Are you going to extract something from the music to develop a theme?Take Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue." It's about America's big cities. It gives you the concept. I think the emotion comes in as to how you approach shooting the film. I work very intuitively so I work with my emotions and let things happen more than I try to make them happen. Do you have any advice to filmmakers who are taking on a project in the IMAX/OMNIMAX format for the first time? There is a lot of homework to be done. There are two different types of formats. You have the OMNIMAX and then the IMAX. Ideally, you would shoot a film tailor-made for an OMNIMAX theater with fish-eye lenses and other lenses and subject matter that work very well on a dome. You have a high contrast print where things can be composed and sound and music all fit the atmosphere of the dome. Unfortunately, what happens is that you shoot a film in IMAX and it ends up in a dome theater and vice versa. You have to be very careful about how you compose your images and what lenses you use to a point where it gets very frustrating at times because you are losing a lot of compositions. You just know it's going to look like hell on the dome. Great on a flat screen but not on the dome. One way out of this is that when you compose with a fish-eye lens you compose it all for a flat screen. If it looks good distorted, then it will look fantastic on a dome. And then vice versa with the flat lenses. You use all your flat lenses to compose for the dome. It's a little bit backwards each way but it allows you to bridge that gap when you're forced into a situation where your film will run in both theaters. It cuts your ability and vision down a bit and you should be very well aware of that. What would you like to see happen in the big frame medium? It would be nice if more independent filmmakers could make films in this medium because it's very attractive to visionary filmmakers—the clarity and the dynamic range of the sound system. Imax Corporation has built a beautiful system and I would like to see films that are more in a personal, creative vein that make the most use of that format, to heighten people's experience about things around them rather than doing it in words and traditional documentary film. | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |