The Billy

Graham Pavilion

at the New York

World's Fair

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Eric Paddon, History teacher, County College Of Morris, New Jersey, USA | Date: 6 March 2005 |

|

|

Further

in 70mm reading: "Man in the 5th Dimension" Todd-AO Todd-AO Films Internet link: This article first appeared on nywf64.com September 2002. Reprinted by kind permission from the author Eric Paddon. |

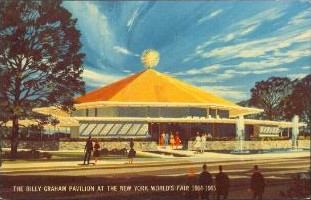

This

sketch by Howard Sanden shows the proposed Billy Graham pavilion

at the 1964-1965 New York world's fair. It will contain an

air-conditioned "theatre-in-the-round" seating approximately six

hundred persons. Ground breaking ceremonies were held February

6. It is expected that five million persons will visit the

pavilion each season of the fair.

Source: Decision Magazine, March 1963 This

sketch by Howard Sanden shows the proposed Billy Graham pavilion

at the 1964-1965 New York world's fair. It will contain an

air-conditioned "theatre-in-the-round" seating approximately six

hundred persons. Ground breaking ceremonies were held February

6. It is expected that five million persons will visit the

pavilion each season of the fair.

Source: Decision Magazine, March 1963A quarter century later, as Robert Moses made his preparations for the 1964 Fair on the same site, he would go out of his way to make this new version of the Fair as friendly to religious sensibilities as it possibly could. This fair would have none of the burlesque side-show attractions of the original's Amusement Area, where such figures as Gypsy Rose Lee had performed at various points. In the end, religion would be represented by no fewer than six distinct pavilions representing all of the major denominations of Christianity as well as an America-Israel pavilion to represent Judaism. In doing this Moses recognized the trends that had seen a rise in American churchgoing since the end of World War II and the onset of the Cold War. Throughout the 1950s, as America took on the perceived role of the defender of Western Civilization, many Americans found strength in the country's religious heritage which had expressed itself as early as the 17th century in John Winthrop's declaration of America as "the shining city on a hill" destined by God for greatness. This renewed burst of American religiosity had led to such symbolic steps as adding "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance and also making "In God We Trust" the country's national motto, and required on all American coins and paper money. It was also a time when Hollywood reflected the trend through numerous productions of Biblical-based movies such as "Ben Hur", "The Ten Commandments" and even the story of former U.S. Senate chaplain Peter Marshall in 1954's A Man Called Peter. |

|

The

Billy Graham Pavilion New York World's Fair 1964-1965. Located

on New York Avenue at Avenue of the Americas, near the main gate

of the fair, this beautiful pavilion houses a film theatre and

exhibits of the world-wide ministry of the Billy Graham

Crusades. Source: BGEA Postcard by Dexter

Press, West Nyack, NY The

Billy Graham Pavilion New York World's Fair 1964-1965. Located

on New York Avenue at Avenue of the Americas, near the main gate

of the fair, this beautiful pavilion houses a film theatre and

exhibits of the world-wide ministry of the Billy Graham

Crusades. Source: BGEA Postcard by Dexter

Press, West Nyack, NYNo single individual better embodied these trends of the last two decades than the Reverend Billy Graham. After rocketing to fame in the late 1940s when the publisher William Randolph Hearst had been impressed by the young preacher's melding of traditional evangelical oratory with strong anti-communist rhetoric, Graham had, in the two decades since, carved out a reputation as America's unofficial national pastor. His crusading activities had taken him across America and around the world and his friendships with Dwight D. Eisenhower and Lyndon Johnson had even made him at times an unofficial presidential advisor. Through it all the evangelist managed to win across-the-board admiration and respect from all denominations, as well as Jewish organizations who approved of how Graham was able to accomplish something none of his predecessors of generations past had done. Which was advocate his simple message of conservative Christian theology while at the same time building bridges of friendship to liberal Protestant, Catholic and Jewish organizations, and avoiding any stigma of bigotry. With this track record it was no surprise that year after year polls always revealed Billy Graham to be among the most admired men in America. Given the temper of the times that led to the creation of the 1964 World's Fair, it was inevitable that if religion were to play a prominent role in the Fair, the Billy Graham Evangelical Association (BGEA) would find a place at the table. (In 1962, the BGEA recognized the value of association with a World's Fair when it sponsored a Crusade in the Seattle area during the height of the Century 21 Fair culminating in a one night rally at the Fair itself for which all amusement areas were shut down in order to accommodate the rally.) The only question though was how would they make their presence felt? |

|

Inside

the pavilion theatre New York World's Fair 1964-1965. Five hundred persons

at a time may be seated in the commodious and comfortable theater. Persons

from foreign countries may hear the message translated into Russian, German,

French, Spanish, Chinese and Japanese through special instruments in certain

seats. Director Dan Piatt and staff of trained counselors deal with those

who inquire after each showing regarding spiritual matters. Inside

the pavilion theatre New York World's Fair 1964-1965. Five hundred persons

at a time may be seated in the commodious and comfortable theater. Persons

from foreign countries may hear the message translated into Russian, German,

French, Spanish, Chinese and Japanese through special instruments in certain

seats. Director Dan Piatt and staff of trained counselors deal with those

who inquire after each showing regarding spiritual matters.On February 17, 1962, the BGEA received its first feeler about participating in the 1964 Fair when Marshall Miller, president of Books International, wrote to BGEA Secretary-Treasurer George Wilson about the plans of the Protestant Council of New York to sponsor a "Protestant Center" pavilion, in which numerous denominations from the Protestant and Orthodox churches would rent individual exhibition space. Owing to the BGEA's prestige within American Protestantism, he said he could " well envision considerable participation by your group in the programs which the Center will sponsor," and added, "Perhaps you may desire to rent space in the exhibition area." When Wilson passed this along to BGEA Teams Leader, Bob Ferm though, he seemed to interpret Miller's latter remark as an indicator that the BGEA might want to rent space outside the Protestant Center altogether which indicated that, from the start, there was some trepidation about having the BGEA presence at the Fair be just part of one group among many in the same building. |

|

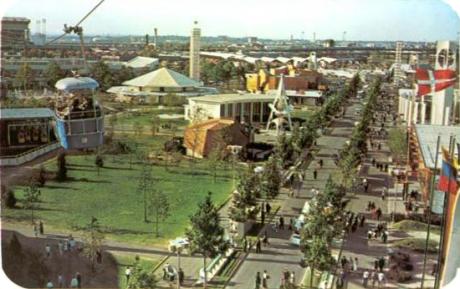

One

of the highlights of a visit to the New York World's Fair is the

lovely Billy Graham Pavilion, located near the main entrance. One

of the highlights of a visit to the New York World's Fair is the

lovely Billy Graham Pavilion, located near the main entrance.By the summer of 1962, after more direct pitches had been made from the Protestant Council about taking part, the BGEA had come to the conclusion that a separate pavilion was more in their best interest. Participation in the Protestant Center would have limited the BGEA to showing a film at designated times in rotation with other denominations that would be offering their films as well. Of more concern to Ferm though was that "our overall conception of evangelistic outreach would be considerably limited or even definitely injured" if the BGEA found itself in the same building surrounded by exhibitions from other Protestant denominations and organizations. "In their striving to be ecumenical," he wrote, "I fear it will be difficult to convey a clear and concise message." He also wondered if part of the reason why the Protestant Center was anxious to have the BGEA's presence in their pavilion stemmed from the realization that Billy Graham's name could be a powerful advertising tool to boost attendance for a presentation that, from the BGEA's standpoint, would not serve their own interests well of trying to use the Fair as a showcase for their evangelical message. |

|

Source:

BGEA Postcard Mailer, Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY. Source:

BGEA Postcard Mailer, Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY.The decision to go for an independent pavilion was reached at a BGEA Board of Directors meeting in June which Graham attended. On August 10, 1962, George Wilson met with Robert Moses and other Fair executives in New York to discuss the guidelines for an independent pavilion. Wilson found Moses quite receptive to the idea of the BGEA having its own building, in part because the scope of Graham's ministry on a global scale entitled him to it. Moses also felt that the Protestant Council had done a poor job with their "Protestant Witness" pavilion at the Century 21 Fair in Seattle and questioned whether they'd be able to raise the money needed for their ambitious plans for New York, which made it more to the BGEA's advantage to go it alone with their own project. The guidelines were laid out as to what the BGEA would have to do, what their pavilion could be like in terms of overall design, and from that point on, there was no turning back as far as their plans for 1964 were concerned. |

|

|

It took a bit longer though, for the Protestant Council to realize that the BGEA was now irrevocably out of the picture as far as the Protestant Center was concerned and this led to some divided reaction. On September 27, 1962, Marshall Miller, now program director for the Protestant Center, wrote to Wilson and urged the BGEA to reconsider its plans for a separate pavilion. He pointed out that while the BGEA had established itself as an organization that had learned to cultivate friendly ties with Catholic and Jewish organizations, it was still nonetheless an integral part of the American Protestant movement and that to have a separate pavilion might confuse the uninitiated, non-churchgoing visitor into thinking that the BGEA itself constituted a separate faith from Protestantism, Catholicism and Judaism in general. He spoke of a conversation with one Fair official who was "surprised to know that the Billy Graham Association was on speaking terms with the Protestant Council" because "he thought your doctrines were quite different from that of Protestantism." Even if the BGEA felt the need to have its own building for more showings of their own movie, he still urged the balance of their participation in the Fair to take place within the Protestant Center. Another letter from former Protestant Council president Emilio Knechtle was sent to Bob Ferm that same week and seemed resigned to the idea that the BGEA intended to go it alone. "I certainly can understand this reason and I have no intention of trying to persuade you to participate in the exhibit of the Protestant Council." Wilson's reply to Miller is not known, but Ferm's reply to Knechtle assured him that the BGEA "would not stand in opposition" to whatever the Protestant Council ultimately did at the Fair and that cooperation on areas of common concern would be possible. From that point on the Protestant Council made no further effort to dissuade the BGEA (eventually, two other Protestant organizations, Wycliffe Bible Translators and Moody Bible Institute, would also go ahead with plans for separate Fair pavilions.) |

|

With plans now finalized for their own pavilion, attention now turned toward getting it designed and built. At the August meeting with Robert Moses it was suggested that an architect be commissioned who would be willing to do the work for nothing or for just out-of-pocket expense and that it would be better to not apply a litmus test of individual belief in finding an architect. In the end, the job of designing the pavilion would go to Edward Durrell Stone, a New York architect who had designed the U.S. Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair, and would show his own brand of ecumenicalism by designing the Christian Science Pavilion for the Fair in addition to the Billy Graham Pavilion. With plans now finalized for their own pavilion, attention now turned toward getting it designed and built. At the August meeting with Robert Moses it was suggested that an architect be commissioned who would be willing to do the work for nothing or for just out-of-pocket expense and that it would be better to not apply a litmus test of individual belief in finding an architect. In the end, the job of designing the pavilion would go to Edward Durrell Stone, a New York architect who had designed the U.S. Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair, and would show his own brand of ecumenicalism by designing the Christian Science Pavilion for the Fair in addition to the Billy Graham Pavilion.Groundbreaking for the Graham Pavilion began on March 1, 1963, but due to illness, Graham was not able to attend. So the ceremonies marking the groundbreaking were pushed back to April 17. All of the Fair's leading officials were present in addition to Graham and the key members of the BGEA. In his remarks, Graham stressed the uniqueness of the pavilion, saying, "We do not intend to duplicate the effort of others." While stressing that the Pavilion would be devoted to its goal of preaching its specific Christian evangelical message, in a nod to broader ecumenicalism he also said, "This pavilion will also be a call to renew our faith in God, whether we be of the Jewish, Catholic or Protestant faith, or whatever religious affiliation." These remarks were vintage Graham, showing how in his powerful, charismatic style he could simultaneously declare his unflagging devotion to the spread of Christian doctrine while at the same time avoid any appearances of being critical of other denominations. In closing remarks, Robert Moses said, "I doubt whether anywhere there is anybody who hasn't heard about Billy Graham, and we are delighted to have him here." The Fair president had also in his remarks noted that the Graham pavilion had a good location to attract crowds, situated on 50,000 square feet near the main entrance on New York Avenue with exits also leading to the Avenue of Europe. The pavilion itself was an octagonal design and eventually went through several modifications. Original seating plans for the theater, estimated as high as 500, were ultimately scaled back to 400. Early plans for a 150 seat chapel were also dropped with counseling rooms located at the back of the theater deemed sufficient for ministry purposes. A later addition was a 100 foot tower next to the pavilion which would prominently display the name "Billy Graham Pavilion" and be topped by a golden sunburst. (This proved to be the one feature that presented problems in construction. The sunburst ended up being damaged in transit on its way to New York and had 15 to 20 of its rods removed before it could be installed. After it was put in place, several more rods fell out prompting a complaint from the BGEA to the contractors that they did not want to be held responsible for any accidents that might arise from more rods falling out, or if the sunburst collapsed altogether, since they had urged it not be installed under these conditions. Eventually, the problem was rectified.) |

|

Example

of 70mm Todd-AO film Example

of 70mm Todd-AO filmThe 50 foot high movie screen would present daily showings of a film produced by the BGEA's film company, World Wide Pictures, entitled "Man In The 5th Dimension." The theme of the 28-minute movie, shot in the expensive 70mm widescreen Todd-AO process, was clearly designed to harmonize Graham's evangelical message of individual conversion to Christ within the framework of the historic and scientific messages to be found in the other pavilions of the Fair. What emerged was a film that presented traditional Graham, preaching through the techniques of storytelling that could also be found in such other Fair presentations as Kodak's "The Searching Eye", Johnson Wax' "To Be Alive", the U.S. Pavilion's "American Journey" and the Travelers Insurance, "Triumph Of Man." Billy Graham was shown at Mount Palomar observatory and in a science lab expressing admiration for what science had been able to tell us about the universe (which in itself demonstrated how far Evangelical preaching had come from the turn of the century when the typical reaction of conservative Christians to scientific discoveries that seemingly conflicted with the Bible was to take the approach that ultimately led to William Jennings Bryan's humiliation in the Scopes Trial). Like "The Searching Eye," viewers were given sights of the wonders of the natural world and the distant universe. Like "American Journey," there was a celebration of the nation's past when Billy Graham quoted George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and Abraham Lincoln to stress the religious principles America had been founded on as the key to her greatness. Like "The Triumph Of Man," Graham highlighted those moments in history that had made a critical difference in man's existence (in this case, the Fall of Adam, and the life, death and Resurrection of Christ). And it could be said that by wrapping the meaning of life up in the need for Christian conversion, "Man In The 5th Dimension" built on the message of "To Be Alive" (which simply celebrated life itself), by noting how much better it feels to be alive once one has converted. Whatever the merits of the film's final content, there could be no disputing that the Graham Association had managed to grasp the underlying pulse of the Fair's broader themes when it came time to putting their stamp on the experience and in so doing succeeded in making the Graham Pavilion a natural part of the Fair's surroundings. |

|

Its

tower is a beacon inviting visitors to the Billy Graham

pavilion. Inside a Todd-AO film and a variety of exhibits

present the religious message of the evangelist. Source: News

Colorfoto by Edmund Peters and Richard Lewis, New York Sunday

News, October 4, 1964 Its

tower is a beacon inviting visitors to the Billy Graham

pavilion. Inside a Todd-AO film and a variety of exhibits

present the religious message of the evangelist. Source: News

Colorfoto by Edmund Peters and Richard Lewis, New York Sunday

News, October 4, 1964When the Fair closed in October 1965, the Billy Graham Pavilion claimed an attendance of over five million, which placed it third overall in terms of attendance for a religious pavilion. (The Vatican Pavilion, with its display of Michelangelo's Pieta, was the overwhelming winner with 27 million attending, second highest of any Fair pavilion, while the Mormon Pavilion drew slightly more than the Graham Pavilion at 5.8 million.) As one of four religious pavilions that required donations rather than admission charges to break even, the Graham Pavilion was the only one that succeeded in doing so. By contrast, the Protestant-Orthodox Center that had tried unsuccessfully to woo Graham for their efforts, only drew half the number of visitors that went to the Graham Pavilion, while their own film "Parable," which required a fifty cent ticket in contrast to "Man In The 5th Dimension"s free admission, only drew half as many visitors as the 1.25 million who saw the Graham movie. The Protestant Center ultimately reported the highest debt of any religious pavilion at the Fair at over $250,000. In terms of actual conversion figures, Dan Piatt, director of the Graham Pavilion, stated that five percent of those who had seen the film, or approximately 5,000, had received counseling from BGEA staff members at the Pavilion, with people from over 55 nations taking part. The Christian Science and Mormon pavilions claimed slightly higher figures for their efforts but Protestantism in general also received a boost in the several thousand claimed each by both the Protestant Center and Moody Bible Institute's "Sermons From Science." Ultimately, Protestant Center Director Dan Potter conceded that the diverse number of pavilions, even among Protestant groups, was "the only way it could have been done here." |

|

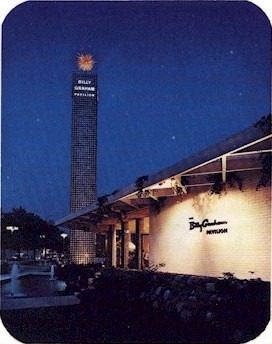

The

pavilion at night, New York World's Fair 1964-1965. Twin sunbursts atop the

Pavilion and the Tower glow in the dark to welcome Fair visitors. Source: BGEA Postcard by

Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY The

pavilion at night, New York World's Fair 1964-1965. Twin sunbursts atop the

Pavilion and the Tower glow in the dark to welcome Fair visitors. Source: BGEA Postcard by

Dexter Press, West Nyack, NYAssessing the long-term impact the Graham ministry had in its efforts in New York is an impossible task given how the organization through the years has never been able to gauge the measure of how many of those who may have taken a first step toward conversion at a Graham crusade or rally were able to follow-up with a subsequently strong Christian commitment. What can be seen from the perspective of 40 years later though, is how the Graham Ministry's involvement at the Fair blended in perfectly with the temper of the times, where the early Cold War period had only heightened the desire for more public acknowledgments of the importance of religion in everyday American life, which had seemingly been ignored at first glance by the organizers of the 1939 Fair. Even as the Fair was ending though, the domestic turbulence associated with America in the 1960s was already beginning to make its presence felt and would ultimately shatter much of that earlier consensus about American society that had existed in the 1950s and early 1960s. While today's polls show that the overwhelming majority of Americans do profess some belief in God, there is seemingly less recognition in a more permissive society today of the importance of religion as an integral part of everyday American life with even many believers stressing more religion's role as a private matter that should not intrude too much upon the broader public world (a mindset that even a strict Fundamentalist or Evangelical in the Graham tradition might advocate today on the grounds that Christianity is better off avoiding the corrupting instincts to be found in today's world through too much interaction). Given that mindset, it is perhaps unlikely that, were an endeavour like the New York World's Fair ever mounted again, one would see the prominence that religion was given at Flushing Meadow in 1964. And if religion were to seem absent from the pictures of everyday life and the prognostications of the future, it is even less likely that there would be any kind of backlash aimed at rectifying it as took place with the Futurama exhibit in 1939. Through that lens then, the presence of the Billy Graham Pavilion at the New York World's Fair, truly represents a window into a vanished part of American life from the middle period of the 20th century. |

|

|

For full coverage of the worlds fair, go to

nywf64.com

and

Billy

Graham Pavilion |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|

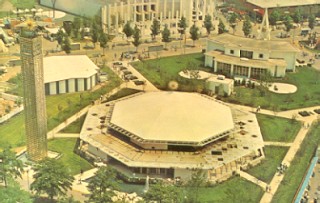

Located

on New York Avenue at Avenue of the Americas, near the main gate of the

fair, this beautiful pavilion houses a [Todd-AO] film theatre and exhibits of the

world-wide ministry of the Billy Graham Crusades. Source: Official Postcard

by Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY

Located

on New York Avenue at Avenue of the Americas, near the main gate of the

fair, this beautiful pavilion houses a [Todd-AO] film theatre and exhibits of the

world-wide ministry of the Billy Graham Crusades. Source: Official Postcard

by Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY