A Distorted View of Todd-AO |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Grant Lobban. First publish in Cinema Technology, 2005 | Date: 17.10.2019 |

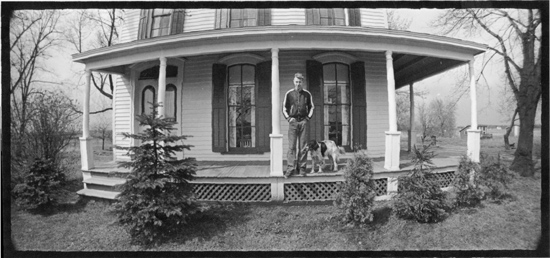

Example of a Todd-AO ‘distortion corrected’ print.

Parking lot at American Optical, Southbridge, MA, USA Example of a Todd-AO ‘distortion corrected’ print.

Parking lot at American Optical, Southbridge, MA, USAThe wide screen revolution in home entertainment has been much slower than the cinema’s rapid change to larger and wider screens in the 1950s. For the last three years or so, we have been celebrating the 50th anniversaries of the various widescreen processes. They began with Cinerama, first seen in 1952, then Cinemascope, which followed in 1953, and VistaVision in 1954. Now in 2005, its the turn of Todd-AO, which successfully introduced the 65mm/70mm format which was to become adopted as an industry standard for theatrical 70mm. In the March 2005 issue of Cinema Technology Mike Taylor looked at the Todd-AO system, and particularly its original projector, the much-loved Philips DP70. This Oscar-winning machine, together with the other ‘multi-purpose’ dual-gauge 35mm/70mm projectors it inspired, made the adoption of 70mm a practical proposition. There were, however, other original aspects of Todd-AO which were less successful and which, for a while, jeopardised its future. A primary source for current news of 70mm and its history, is “The International Newsletter About 70mm”, the creation of Thomas Hauerslev in Denmark. Over the years, Thomas has met and talked to many personalities about their experiences in the world of 70mm. To mark Todd-AO’s 50th birthday, he has recently published an interview with Walter Siegmund, which is carried in this issue of Cinema Technology. Back in 1953, Walter was a young optical science graduate who was recruited by Dr. Brien 0’ Brien at the American Optical Company to help bring producer Mike Todd’s conception of a simplified version of Cinerama to the screen. One of Walter’s first tasks was to go and see Cinerama. He reported back that the huge ultra-wide angle image coming from three separate 35mm projectors and blended together on its deeply curved screen was-a “WOW”! Strangely, this reaction didn’t prompt the Doctor to immediately set off to see it for himself. If he had, he might have appreciated more the difficulties which would lie ahead trying to keep to Mike Todd’s brief that ever thing must come out of “One Hole”. If Cinerama’s inventor, Fred Waller, had been able, during the ten years it took to develop, to produce the same image using only a single film and projector he surely would have done so, rather than having to end up using the cumbersome and costly triple-lens system. |

More in 70mm reading: New cinema history book "All Shapes and Sizes" Who is Grant Lobban? Walter Siegmund Interview TODD-AO PROCESS • Films | Premiere • People | Equipment • Library | Cinemas • Distortion Correcting • DP70 / AAII Projector • Todd-AO Time Line • Who developed Todd-AO in70mm.com News Peripheral Vision, Scopes, Dimensions and Panoramas in70mm.com's Library Presented on the big screen in 7OMM 7OMM and Cinema Across the World Now showing in 70mm in a theatre near you! 70mm Retro - Festivals and Screenings |

An

early black & white test of Todd-AO. The camera was fitted with a 128 degree

‘bug-eye’ wide-angle lens to try to match Cinerama’s 146 degree angle of

view. The severe ‘barrel’ distortion limited its use when used later in

actual productions. An

early black & white test of Todd-AO. The camera was fitted with a 128 degree

‘bug-eye’ wide-angle lens to try to match Cinerama’s 146 degree angle of

view. The severe ‘barrel’ distortion limited its use when used later in

actual productions.Mike Todd had been associated with Cinerama, but wanted his new process to be easier to install with less disruption to the theatre’s normal operation. Cinerama required that three new carefully positioned projection boxes be built at the rear of the stalls to provide near level projection of the three films onto the screen, sharing out the deep curve. For Todd-AO, the single 70mm projector was to be installed in the theatre’s existing projection room, even if this was was situated high up above the balcony. Any film hitting the screen from a steep angle shows the familiar ‘keystone’ effect caused by the increasing magnification towards the bottom of the screen as it becomes further away from the projector. This is usually hidden by masking off the over-spilling image by using a specially shaped aperture plate and sometimes by tilting the screen back to face the projector. If the screen is also deeply curved, the distortion is much more serious, with the picture curving up at the sides. This is far more noticeable to the audience, with curved horizons and strange effects, like ships sailing uphill. Walter joined the team given the job to find a solution to the problem. The method finally chosen was to purposely distort the image on the 70mm print to counter-balance the distortion on the screen. The picture on the film was bent up into an arched shape to correct the sagging effect caused by the screen. To achieve this, a special ‘secret’ continuous optical printer was devised. A normal intermittent optical printer takes the form of a projector head projecting its images via a lens system into the gate of a camera. It is slow but very versatile; for example it can print from a different sized original and change the size or shape of the image, e.g. anamorphic conversions. A high speed continuous printer simply runs the negative and positive films together over a common sprocket with the exposure made using a narrow slit of light. Less common is a continuous optical printer which separates the two films with the image-forming slit relayed to the print stock by a lens. It can be used to copy shrunken film which will not run over a common sprocket, with the optical system adjusted to restore the size of the image. Todd-AO's variation was to slightly reduce the magnification of the image-forming slit as the negative and print stock moved the distance of one frame. This produced the required distortion, and the amount of change could be adjusted for the different intended projection angles. The lens system had to be reset between frames, so the printing process was relatively slow. |

|

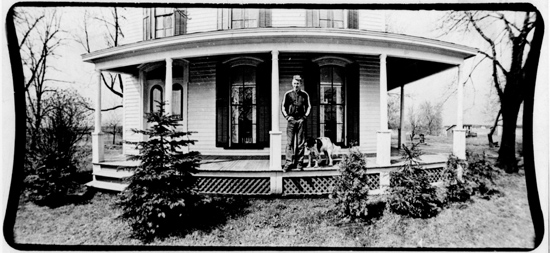

An

early black & white test of Todd-AO, with barrel distortion optically

corrected. An

early black & white test of Todd-AO, with barrel distortion optically

corrected.Although a clever idea, its use was going to spoil Todd-AO’s debut. The printer was used to provide the print destined for the premiere of the first Todd-AO feature OKLAHOMA! at the Rivoli in New York. The deadline prevented the printer from being fully perfected. For example, it had no method, like a liquid gate, to suppress the visibility of scratches and other blemishes, and in fact the specular nature of the optical system accentuated them. As a result the print shown ‘sparkled’ with white specks. To add to this, the degree of distortion correction didn’t quite match the theatre’s rake, so the picture still looked bent. Although the film itself received good reviews, Todd-AO got the thumbs-down, with critics suggesting that its developers go back to the drawing board to correct its flaws. Walter and the team at American Optical had also failed to find a reliable way to manufacture a highly reflective single-sheet screen with different directional characteristics across its width, so a lower gain deeply curved screen had to be used, which was far less successful than Cinerama’s louvred design at reducing the cross reflections. Soon the decision was made to give up trying to emulate Cinerama and to project normal prints onto a flat or only a slightly curved screen, and when necessary relocate the projection box down to a lower level. In its new form, Todd-AO went on to be a success in its own right, now clearly showing the advantages of 70mm presentation. Its superb images ensured that it shared in the Oscar winning acclaim of the second Todd-AO feature, Mike Todd’s AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS, in 1956. A year later, the process received an Academy Scientific and Technical Award, shared by the Westrex Corp. for its equally superb sound. Walter Siegmund’s own story of the development and launch of Todd-AO is fascinating, with many more details of the technical aspects and personalities involved. Although some of his memories are tinged with failure, he still enjoyed his time working alongside the many film people he met, before, like his boss, Dr. O’Brien, he left the world of showbiz to continue his career working on other optical projects. Like today's cinemas, Thomas’s Newsletter has begun the process of going digital, and you can find the whole story (as well as in Cinema Technology) and much more about 70mm, by pointing your web browser at www.in70mm.com. |

|

... and not forgetting |

|

|

The idea of altering the shape of the image on the film to

counter balance the effect of projecting it onto a deeply curved screen was

tried again some ten years later. Special 70mm ‘rectified’ prints were made

as an option for showing in the later single-lens version of Cinerama and

its rival Dimension 150. Both used level projection, so the correction was

confined to just squeezing up the image towards the sides of the frame to

compensate for the stretching effect of the concave surface of the screen. Although this gave a better picture for those sitting at the sides of the auditorium, when viewed head-on the built-in distortion was still noticeable and worse than watching a normal print. In general, these special prints were considered more trouble than they were worth, particularly so if later reissued and shown on flat screens. The apparent non-linear distortion was sometimes blamed on the film being photographed or projected with a dodgy lens. The result was rather like the ‘Panoramic’ option on a widescreen TV, when a 4x3 picture is progressively stretched out at the sides to make it fill a 16x9 screen. This ploy usually looks OK, until the camera pans and gives it away. If deeply-curved screens ever become fashionable again, in this new age of digital projection, the balancing distortion could be done electronically in the projector and fine tuned for the best compromise when viewed from different angles, although, in theory anyway, any correction will only work for a single viewing position. Although the Philips DP70 was the first commercially available Todd-AO projector, during the development of the process old equipment from an earlier failed attempt to introduce wide-film systems was brought out of retirement. The camera was a Fearless Super Film camera made by the Fearless Camera Corp. in 1930. It was used back then to photograph a 65mm version of THE BAT WHISPERS. When acquired by Todd-AO, it had already been recycled for an unsuccessful colour process, Thomas Color, in 1947. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |