Ultra Panavision 70

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Rick Mitchell, Film Editor/ Film Director/ Film Historian | Date: 6 March 2005 |

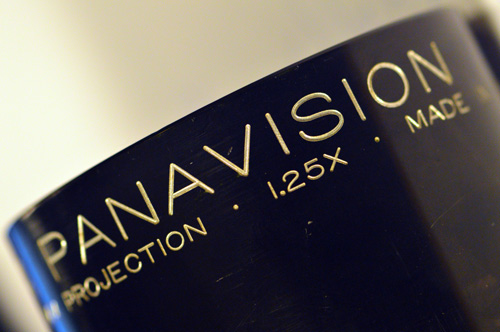

Fifty years after the Wide Screen Revolution, film and wide screen buffs living in Los Angeles, Seattle, and Bradford, England have had rare opportunities to see two of the processes whose special presentation requirements have made them generally unviewable for over 35 years - three panel Cinerama and Ultra Panavision 70. Fifty years after the Wide Screen Revolution, film and wide screen buffs living in Los Angeles, Seattle, and Bradford, England have had rare opportunities to see two of the processes whose special presentation requirements have made them generally unviewable for over 35 years - three panel Cinerama and Ultra Panavision 70. The two processes are interestingly related: Michael Todd, one of the original promoters of Cinerama was unhappy about Fred Waller's inability to minimize the visible joins between the three panels and approached Dr. Brian O'Brien of the American Optical company about developing a "Cinerama out of one hole." Dr. O'Brien concluded that this could be achieved via a larger negative and frame and using 65mm equipment from the industry's aborted Wide Film revolution of 1929-30, determined that an effect comparable to Cinerama could be achieved via images photographed with a very short focal length, almost fisheye lens projected onto a deeply curved screen, even if the resulting image wasn't actually as wide as Cinerama. In the fall of 1953, Todd-AO, the company formed to exploit the process, rented MGM's Stage 30 and set up projection equipment for tests thereon. Douglas Shearer, head of R & D at MGM as well as its Sound Department, no doubt saw tests before they were officially shown in the Spring of 1954. Shearer had established a working relationship with Robert Gottschalk, founder of the recently formed Panavision Corporation, whose variable squeeze anamorphic lenses for CinemaScope he'd found superior to similar lenses being promoted by the Tushinsky Brothers as well as the "official" CinemaScope projection lenses being vended by Bausch & Lomb and others. Shearer no doubt told Gottschalk about Todd-AO, possibly even arranged for him to see tests. Whose idea it was to apply anamorphic elements to the basic Todd-AO format to achieve a wider image, or why they chose an aspect ratio that was wider than either Cinerama or CinemaScope, has never been determined. But in 1963, when this format was adopted as the basis for "single film Cinerama", it literally did become Todd's "Cinerama out of one hole." For the record, Cinerama never published an official aspect ratio. The math for the camera aperture specifications works out to 2.59:1, but because the process was being put into existing movie palaces, allowances were made for problems stemming from the architecture of various houses necessitating a lower height or a not quite as wide image, which was allowed for in photography. Projection aspect ratios as wide as 2.66:1 have been cited for Cinerama. That, of course, was the aspect ratio of CinemaScope's negative image, used for all the CinemaScope productions shot before the decision was made to put magnetic stripes on the special CinemaScope perforated prints. This reduced the projection aspect ratio to 2.55:1, the standard 100 mil. optical track reduced it further to 2.35:1. The format Gottschalk and Shearer developed, combining Todd-AO's ultimate 2.2:1 aspect ratio (with magnetic stripes on the prints) with a 1.25x anamorphic squeeze resulted in an aspect ratio of 2.75:1! (A 1.33x squeeze was considered but never implemented, though that ratio was marked on some early lenses; see the Ultra Panavision wing of widescreenmuseum.com for an illustration.) Due to a financial investment from MGM, the new format was initially known as "MGM Camera 65". Because, unlike Todd-AO, one of its design considerations was to yield higher quality 35mm anamorphic prints (apparently to be made by Technicolor in its dye transfer process as, at the time, they were the only American lab doing 65/70mm processing and printing), directors, cinematographers, and camera operators were instructed to keep important action within the safe action area of 2.35:1 anamorphic 35mm prints with an optical track. (In fact, a fair amount of space had always been left around the frame even in the silent days to allow for variations in masking in different theaters.) While MGM and Panavision devoted most of their attention to the production format, apparently they assumed that there would be greater expansion of the Todd-AO presentation format, on which they'd founded Camera 65 for compatibility, than had actually occurred by the time their first film in the process, "Raintree County", was ready for release in the Fall of 1957. The few theaters then equipped to show 70mm were tied up with Todd's "Around the World in 80 Days" and committed to follow it with "South Pacific". While it's understandable why MGM didn't go to the expense of setting up the Brown Theater in Louisville, KY, where the film premiered, for the process, why they didn't do so for the New York and/or Los Angeles theaters in which it was roadshown is a subject for further research. Thus this film has never been publicly shown in 70mm; even the screening attended by Variety's reviewer was in 35mm. However, cinematographer John Hora remembers seeing a 70mm print at MGM when he was a USC Cinema student in the early Sixties. And the daytime Civil War battle sequence was blown up to three panel Cinerama for use in "How The West Was Won" (1962) (Technicolor had done test blowups of Ultra Panavision to Cinerama and Technirama to 70mm as early as 1958). I don't know the condition of the dyes in the "Raintree County" negative, but given the contemporary low opinion of the film, it probably isn't worth the cost of striking a new 70mm print. The success of the 70mm roadshow engagements of "Around the World in 80 Days" and "South Pacific" and announcements of future 65mm productions, 20th Century-Fox's deal with Todd-AO, and Panavision's introduction of its own Todd-AO compatible nonanamorphic 65mm camera led to a radical increase in 70mm installations around the country, but this would create an interesting problem for Camera 65: many of these theaters had reached the width limit of their prosceniums with CinemaScope and compromised by showing 70mm prints at the same width but taller than they ran 35mm anamorphic. As a result, only Cinerama theaters and a handful of big movie palaces which had additional screen space were able to show the next Camera 65 production, "BEN-HUR" (1959), and subsequent Ultra Panavision productions at anything approaching their full 2.75:1 aspect ratio. As Technicolor made its 70mm prints from 65mm negatives on an optical printer, it was able to make both "squeezed" and "unsqueezed" 70mm prints off the original cut negative, ultimately to its detriment. I have not been able to confirm if further allowance was made for the even narrower 2.2:1 aspect ratio of non anamorphic 70mm in photographing subsequent Ultra Panavision films. (Technicolor also made select 35mm IB prints of "Raintreee County" and "Ben Hur" "letterboxed" to reproduce the 2.75:1 ratio within the 2.35:1 frame.) (John Hora saw "Ben Hur" and "Muntiny on the Bounty" in their roadshow engagements at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood and remembers being impressed by the unusually wide images on a basically flat screen. This theater had a flat screen when I got here in 1967 and although both "Knights of the Round Table" (1953) and "Oklahoma!" (1955) had their local premieres there, I have not been able to confirm if it ever had a curved screen prior to putting in Dimension 150 in the late Sixties; contrary to information that has appeared elsewhere, 70mm Dimension 150 prints of "Patton" were never publically shown at the Egyptian while it was set up for the process, it premiered on the flat screen of the Pantages.) |

Further

in 70mm reading: List of Ultra Panavision 70 films The MGM PANAVISION Enlarged-film System Ultra Panavision 70 Lens - Adjustment and lens modifications Ultra Panavision 70, Early lenses The Importance of Panavision The Hateful Eight - in 65mm?? An Homage To D. W. Griffith |

Ultra Panavision 70 |

|

In 1962 Panavision got full rights to Camera 65 and renamed it Ultra Panavision to distinguish it from its nonanamorphic 65/70mm format previously called Panavision 70 and now called

Super Panavision. The Ultra Panavision credit first appeared in the souvenir program for

"How the

West Was Won", which noted: "Certain sequences photographed in Ultra Panavision" (I recall this credit being on the original Cinerama print I saw in New York in 1963 but it is not in the credits of the recently struck three-panel print which does carry the lab credit for Technicolor that was replaced by MetroColor in the 35mm general release prints; Ultra Panavision was used for action sequences which were difficult to do with the three panel camera and for full screen rear projection, which would have been impossible with it, though rear projection was used for a scene in a railroad car in

"The Wonderful of the Brothers Grimm" (1962)). The first film to officially carry it was MGM's

"Mutiny on the Bounty", released in December, 1962; it had been listed as being in Camera 65 while in production.) In 1962 Panavision got full rights to Camera 65 and renamed it Ultra Panavision to distinguish it from its nonanamorphic 65/70mm format previously called Panavision 70 and now called

Super Panavision. The Ultra Panavision credit first appeared in the souvenir program for

"How the

West Was Won", which noted: "Certain sequences photographed in Ultra Panavision" (I recall this credit being on the original Cinerama print I saw in New York in 1963 but it is not in the credits of the recently struck three-panel print which does carry the lab credit for Technicolor that was replaced by MetroColor in the 35mm general release prints; Ultra Panavision was used for action sequences which were difficult to do with the three panel camera and for full screen rear projection, which would have been impossible with it, though rear projection was used for a scene in a railroad car in

"The Wonderful of the Brothers Grimm" (1962)). The first film to officially carry it was MGM's

"Mutiny on the Bounty", released in December, 1962; it had been listed as being in Camera 65 while in production.)Now occurs another area for further research. The "proper" presentation of Camera 65 films in Cinerama houses, and the use of the process to photograph action sequences in "How the West Was Won" no doubt stimulated interest in using it to solve the problems with three panel Cinerama, even if the maximum 92 degree field of view of its shortest lens did not yield the faux stereoscopic effect of the 146 degree field of view achieved by Cinerama's three 27mm lenses, Todd-AO's "bug-eye" lens, the later Dimension 150's shortest lens, or even 35mm anamorphic lenses of 40mm or shorter. However, the Cinerama Corporation did conduct experiments, sometimes in conjunction with Panavision, and, according to press releases of the time, by June, 1963 had achieved sufficient success to start rush construction on a new theater designed to exploit the new format if Stanley Kramer's Ultra Panavision shot roadshow comedy "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World" would be ready by November. It was, dooming the three panel Cinerama process, and except for Samuel Bronston's already in production "Fall of the Roman Empire" (1964), all subsequent Ultra Panavision productions would initially be roadshown as "Cinerama presentations": "The Battle of the Bulge" (Warner Bros.), "The Greatest Story Ever Told" and "The Hallelujah Trail" (both 1965) and "Khartoum" (1966; all United Artists). 70mm prints of the Technirama shot "Circus World" (Paramount; 1964) were also shown as "Cinerama" presentations as were reportedly a number of blowups from 35mm anamorphic in Europe. Though "2OO1: A Space Odyssey" (MGM; 1968) had been conceived as a 65mm shot single lens Cinerama roadshow, director Stanley Kubrick rejected the use of Ultra Panavision and the heavy lenses were problematic for mounting on race cars for "Grand Prix" (MGM; 1966). The success of these films in their "Cinerama" engagements doomed the use of Ultra Panavision, though some shots for "Ice Station Zebra" (MGM; 1968) were reportedly done with the lenses. Supposedly the last "proper" presentation of an Ultra Panavision film in the 20th Century was a screening of "The Greatest Story Ever Told" at the modified for Dimension 150 Egyptian Theater during the 1974 Filmex. (Because this screening was held on a weekday, I was unable to attend and can't confirm if a 70mm print was actually shown.) Faded surviving prints of earlier films have been shown in Bradford, England and other sites around Europe, but only privately in the United States, whose video addled audiences apparently will no longer sit through less than perfect prints. In the Fall of 2003, at the behest of Mrs. Stanley Kramer, MGM/UA, the current owners, struck a new 70mm Ultra Panavision print of "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World", running it for five days on the full width screen of the Cinerama Dome. "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World" was not shot with the intention of being a "Cinerama" presentation so there are very view of the dynamic POV shots associated with the three-panel process, but they are quite effective. Alternately, the film has a number of scenes in which up to eight actors are grouped across the frame in medium shots that work quite well. Overall the film is well composed for the format The new print is state-of-the-art, the negative showing no sign of damage or fading. This is the 157 minute version as the negative for the deleted footage is not known to exist. The overture, en'tracte, and walk out music have been restored as well as the police calls heard during the intermission, though repeated three times for some reason. The sound, in DTS' Special Venue format, appears to be the original 6 track mix, so voices match their on-screen source, etc. And on Nov. 22, 2004, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences ended its two month tribute to George Stevens with a screening of a new Ultra Panavision 70 print of "The Greatest Story Ever Told". This was apparently a check print struck as a guide for subsequent video transfer and had an overall bluish cast, correctable if another print were to be struck. It was run double system with 6 track magnetic sound. For the presentation at the Academy's Samuel Goldwyn Theater, the overall picture size had to be reduced and there was some question as to whether or not it was actually being shown at 2.75:1 though there seemed to be no image cutoff. |

|

"The

Greatest Story Ever Told" has come to be one of the most controversial films ever made, but perhaps being seen at the end of a retrospective of Stevens' films makes it look better, for it is within the tradition of his oeuvre. Like most of the directors who had roots in silent film, Stevens was a cinematic storyteller, in many ways more so than Ford or Hitchcock, using the resources of the film medium to tell his tale the way authors use words. Excerpts from interviews George Stevens, Jr. did for his 1985 documentary

"GEORGE STEVENS: A FILMMAKER'S JOURNEY" shown throughout the retrospective recount his obsessiveness with the propriety and authenticity of sets and locations, set decorations, costumes, even on-set mood music. As a result, even with his frequent crossing-the-stageline in editing and voluminous dissolves, you always know where you are and the characters are in a Stevens film. And you are very much aware of the environment in which the action is taking place. And his performers are not self consciously actors enacting real scenes but real people going about their daily lives. Even his famous slow pace works in his favor;

"VIVACIOUS LADY" (1938) and "THE MORE THE MERRIER" (1943) are actually a lot funnier because they aren't frenetic. "The

Greatest Story Ever Told" has come to be one of the most controversial films ever made, but perhaps being seen at the end of a retrospective of Stevens' films makes it look better, for it is within the tradition of his oeuvre. Like most of the directors who had roots in silent film, Stevens was a cinematic storyteller, in many ways more so than Ford or Hitchcock, using the resources of the film medium to tell his tale the way authors use words. Excerpts from interviews George Stevens, Jr. did for his 1985 documentary

"GEORGE STEVENS: A FILMMAKER'S JOURNEY" shown throughout the retrospective recount his obsessiveness with the propriety and authenticity of sets and locations, set decorations, costumes, even on-set mood music. As a result, even with his frequent crossing-the-stageline in editing and voluminous dissolves, you always know where you are and the characters are in a Stevens film. And you are very much aware of the environment in which the action is taking place. And his performers are not self consciously actors enacting real scenes but real people going about their daily lives. Even his famous slow pace works in his favor;

"VIVACIOUS LADY" (1938) and "THE MORE THE MERRIER" (1943) are actually a lot funnier because they aren't frenetic.In the mid-Fifties Stevens and Fritz Lang were Hollywood's most vocal opponents to wide screen; ironically both used it brilliantly when they finally worked in it. Indeed, Stevens' style was especially suited to wide screen. A point overlooked by Steven Spielberg in his introduction to a clip from "The Diary of Anne Frank" (1959) at the opening night tribute was how Stevens and William C. Mellor's use of CinemaScope also enhanced the suspense of the scene in question, as well as the suspense and drama of the entire film. "The Greatest Story Ever Told" was actually started in three-panel Cinerama, though I've never been able to find out on which scenes it was used. I don't know if Stevens used storyboards, but he kept that vision when he switched to Ultra Panavision. The film is a visual treat, beautifully composed for the format. I didn't take my eye off the screen during the entire 197 minutes. (This is the official version, no prints or underlying elements on the original 225 minute version are known to exist.) Although sites recognizable as the American Southwest are initially disconcerting, the ancient Judea created upon them and on the backlot of the now Culver Studios by Richard Day and William Creber have a far more natural, lived-in feel than that of most epics (and unlike the recent spate of epics, you actually do get to see them!) And despite the usual clash of accents, particularly Max Von Sydow's Swedish one vs. the predominately American and mid-Atlantic of most of the others, as noted before in Stevens' films, in the end all the actors come across as real people, not actors portraying real people. That may, in fact, the source of the problem most people have had with the film. It is not hokily De Milleian nor self consciously and dully anti-De Milleian like "The Fall of the Roman Empire". It seems to be aimed at neither the heart or the intellect but somewhere in between. Jesus, of course, is really an impossible character to depict. De Mille's "King of Kings" (1927) deals more with Judas Iscariot and Mary Magdalene than Christ and more recently Mel Gibson's "The Passion of the Christ" treated Him as a rather stoic reactor to all that's going on around him. Stevens' Jesus is, in fact, in the tradition of all his protagonists, a confident, straight ahead striver, who, in this instance, like "A Place in the Sun"'s George Eastman and "Giant"'s Bick Benedict, is brought down by forces beyond His control, though in this instance he ultimately triumphs. It's actually something of an early 20th Century Middle American Protestant approach to the subject and it would be interesting to learn the degree to which it was influenced not only by Carl Sandburg but credited co-writer James Lee Barrett, whose subsequent career is worth evaluating in this context. Pan/scan video has been no more help to serious evaluation of "The Greatest Story Ever Told" than it was to "The Diary of Anne Frank", and I'm not all that certain that the reduced image for "letterboxing" is really much of an improvement. Both films benefit best from being seen large on a proper width screen. (I'd always refused to watch "The Greatest Story Ever Told" on a pan/scan 16mm print or video, so had only seen it once previously, a 35mm IB print run at LACMA in 1996.) I don't know if a color corrected 70mm print would be more of an attraction at the commercial venues equipped for Ultra Panavision than some of the other films in the format, "Ben Hur" obviously would do good business, but hopefully it will get shown again this way, as might some, if not all, of the others while there are still venues for doing so |

|

Note |

|

|

Please note that beyond doing a quick spot check of

in70mm.com and

widescreenmuseum.com, I've done no specific research for the following beyond what I have immediately on hand, most of which is five to ten years old. Therefore answers to questions I raise or errors stemming from incorrect information from back then may be found in more recent and verified publications such as Film History or David Strohmaier's

researches into Cinerama. I would appreciate this not being

cited as a definitive reference source but a foundation for

further research which I myself will be doing in the future. |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|