"Ryan's Daughter" Revisited

|

This article first appeared in |

| Written By: Tony Sloman | Issue 54 - September 1998 |

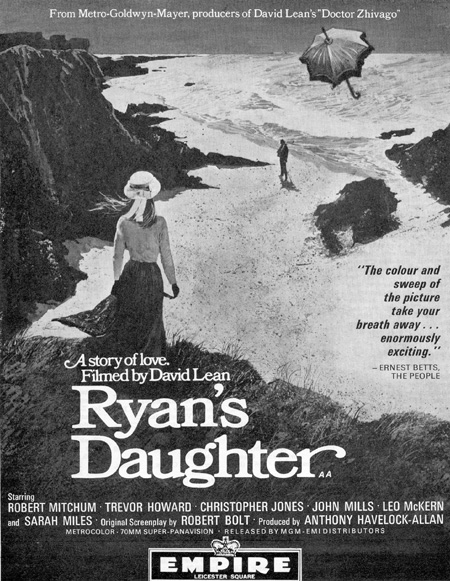

I well remember seeing "Ryan's Daughter" on its premiere run in 1970 at

London's magnificent Empire Cinema, Leicester Square, before commercial vandalism had turned that mighty Picture Palace - the self-styled Showplace of the Nation - into half its former size, the other half now a noisy discotheque. I went to an afternoon matinee, the easier to get the seat I wanted, but well after the film had opened to universally unfavourable reviews. Hard, as a cineaste, to ignore the critical battering, but eager to see what was to be the last feature actually photographed in 70mm (until, that is, comparatively recently) in all its intended glory: on the giant screen and with full 6 track magnetic stereophonic sound, preceded by the unfurling of the fulsome Empire double valance, one of the

world's great presentation curtains. And then guess what? I dozed off - not properly fell asleep, you understand, just nodded off periodically throughout the seemingly interminable running time (206 mins.), and then only occasionally, but nevertheless.... This was, after all, the new motion picture by one of the greatest living masters of cinematic storytelling (though that was a time when many such were still with us), the King of the Big Screen, the director who had blown up the Bridge on the River Kwai (though only in CinemaScope, not in 70mm), toiled with

"Lawrence in Arabia", and watched the Russian Revolution itself through the eyes of a Doctor called Zhivago, mighty movies all. So why did I fall asleep now? It seemed to me, callow youth that I then was, that

"Ryan's Daughter" was a small story, akin to Lean's finest film "Brief

Encounter", and did not merit the huge screen, the tremendous care, in the telling, the elaborate dwelling on all aspects of the drama. How presumptuous I was, and how very wrong. And how very ignorant of the facts of life themselves, an ignorance then (but not now) of the forces of destiny that engender a tale like that of Rosy Ryan, and how common it is, and how clever this movie that hides its precious kernel in the widest of wide screens. But I was not alone in my short-sightedness, and the critical reaction to this film damaged director David Lean's self-confidence so greatly as to render him cinematically impotent for 14 years. I well remember seeing "Ryan's Daughter" on its premiere run in 1970 at

London's magnificent Empire Cinema, Leicester Square, before commercial vandalism had turned that mighty Picture Palace - the self-styled Showplace of the Nation - into half its former size, the other half now a noisy discotheque. I went to an afternoon matinee, the easier to get the seat I wanted, but well after the film had opened to universally unfavourable reviews. Hard, as a cineaste, to ignore the critical battering, but eager to see what was to be the last feature actually photographed in 70mm (until, that is, comparatively recently) in all its intended glory: on the giant screen and with full 6 track magnetic stereophonic sound, preceded by the unfurling of the fulsome Empire double valance, one of the

world's great presentation curtains. And then guess what? I dozed off - not properly fell asleep, you understand, just nodded off periodically throughout the seemingly interminable running time (206 mins.), and then only occasionally, but nevertheless.... This was, after all, the new motion picture by one of the greatest living masters of cinematic storytelling (though that was a time when many such were still with us), the King of the Big Screen, the director who had blown up the Bridge on the River Kwai (though only in CinemaScope, not in 70mm), toiled with

"Lawrence in Arabia", and watched the Russian Revolution itself through the eyes of a Doctor called Zhivago, mighty movies all. So why did I fall asleep now? It seemed to me, callow youth that I then was, that

"Ryan's Daughter" was a small story, akin to Lean's finest film "Brief

Encounter", and did not merit the huge screen, the tremendous care, in the telling, the elaborate dwelling on all aspects of the drama. How presumptuous I was, and how very wrong. And how very ignorant of the facts of life themselves, an ignorance then (but not now) of the forces of destiny that engender a tale like that of Rosy Ryan, and how common it is, and how clever this movie that hides its precious kernel in the widest of wide screens. But I was not alone in my short-sightedness, and the critical reaction to this film damaged director David Lean's self-confidence so greatly as to render him cinematically impotent for 14 years.Eventually I programmed a Lean season at London's National Film Theatre, including the privilege of interviewing the great man himself on the stage of the NFT, and naturally I looked forward to re-seeing "Ryan's Daughter", with a view to reassessment (and seeing the bits I'd slept through, though I'd caught them on TV, but that doesn't really count). After all, it had won Oscars for best supporting actor (John Mills, whom I thought merely grotesque at the time) and for Freddie Young's stunning photography. Since the season was pegged on the new 70mm reissue of "Lawrence of Arabia", there was no question that I would screen "Ryan's Daughter" in 35. Except I was informed that no 70mm prints of "Ryan's Daughter" existed anywhere in the world, not in MGM vaults, nor in the BFIs own vaults - nowhere. I made a fuss, and said it was a disgrace, and that the BFI must print one for the the season, but I knew in my heart of hearts that I was on a hiding to nothing, for printing up a 70mm from an original 65mm negative and striping it would prove prohibitively expensive, (though that's partly what the BFI should be about). So we screened a 35mm Panavision copy. At least, I told myself, that's better than watching it panned-and-scanned, and probably cut, on television. Earlier this year Bill Lawrence of Bradford's estimable Wide Screen Weekend called me (I had in the intervening years - immodestly - become regarded as some authority on wide screen cinema) and asked if I would deliver the lecture I had successfully given at the BKSTS anamorphic seminar at Pinewood, along with another lecture on digital editing. I was honoured and delighted to be asked and casually questioned Bill as to what he was screening - "Oh come up early", he replied, "-, and you can see "Ryan's Daughter" Friday night -we've got a 70mm print from the Swedish archives" [Actually from Norway, editor]. So much for the BFI's research! I was very excited anyway, with the promise of a solid weekend's worth of other 70mm treats, but this was astounding - a pristine 70mm, albeit with foreign sub-titles, but no matter, of a major movie actually filmed in 70mm that I had assumed was lost in it's correct gauge. I could barely wait! In Bradford that evening, Bill asked me whether I thought it should be shown on the giant deep curved Cinerama screen, or on the huge, but flat, wide screen. A difficult decision, and a big responsibility, but bearing in mind Lean's own recently-aired views on screen curvature affecting his horizons and causing unwanted reflections on the re-release of "Lawrence of Arabia", I opted for the latter (Though, truth to tell, I myself would have preferred the former, to try to recapture my Empire experience, and I hope to have that opportunity at Pictureville on a later occasion sometime in the future). And so, twenty eight years later, to "Ryan's Daughter" in 70mm. The titles seemed pinkish, and this boded badly for the rest of the film but, oh! that majestic opening, with dubbing editor Winston Ryder's wind effects and composer Maurice Jarre's picking out the notes to the main theme -what a magnificent use of stereo! And if the clouds seemed slightly pink, it didn't matter - this was cinema of a style I fear we'll not see again, and as the music built, and those great production names appeared in the credits (Freddie Young, Anthony Havelock-Allen, David Lean himself) one felt in the presence of masters. Fortunately, it was only the titles that were on the pink side, the rest of the print showed but bare traces of colour fading, and as Rosy Ryan appeared on the cliff top, losing her black lace parasol to the elements, only to have it retrieved by Father Collins and Michael down below, I realised the sheer cinematic perfection of this stunningly-shot wordless opening, and was made clearly aware of how in particular the 70mm negative enhances this work particularly early on in the movie before the clarity falls secondary to the tale itself: Rosy's abandoned shoes, Michael's writhing lobster, the hurt on Michael's face as his gift of the claw is rejected (and how had I cynically failed to recognise the brilliance of John Mills´ performance?). Gradually, one realised that it´s the close-ups that are undervalued in 70mm. The vistas, true, are impressive, but the fine location shooting is itself self-evident. It's the huge screen's attention to every skin pore and to every hair follicle that allows the faces to live and breathe, and not just pass muster as Hollywood cosmeticity. Note particularly gnarled Trevor Howard's priestly visage as he delivers key dialogue "Doin' nothin's a dangerous occupation" and "Devil take me if the lot of you aren't possessed and damned", but most especially a lovingly-lit important line after his pre-nuptial chat with Rose, as in answer to him she looks skywards at the circling birds - "Wings, is it?" A great, great close-up, unsurprisingly diminished when not seen in 70mm. What the giant screen does not service well are the interiors, both in Ryan's pub and the Shaughnessy cottage, both of which seem over expanded and sparse on the great expanse. (You could argue, though, aesthetically, that this increases a sense of personal isolation from the surroundings). Set against that, however, are the magnificent landscapes, the sea and its adjacent beach where, as with the same director and cinematographer's "Lawrence of Arabia", you can virtually touch every grain of sand, so sharp is the image, and there's absolutely no doubt at all that the many horizon shots (Rose on the beach; Major Doryan arriving by bus) demand the huge (uncurved?) screen. There is a downside, however. The giant screen only serves to reveal that the great Robert Mitchum, though excellent as ever, looks even more miscast than I'd remembered. Paul Scofield (who had won an Oscar for his work in a previous Robert Bolt screenplay) was the original choice for the role of Flaubert's Charles Bovary as an Irish schoolmaster, and producer Anthony Havelock-Allan rightly preferred the more passive Gregory Peck, but perhaps the role was, in truth, actually unplayable. Be that as it may, it's hard to accept Big Mitch pressing flowers in a book while his feline young bride sits patiently crocheting by his side. And, anyway, Bob Mitchum would have flattened anyone who laid a hand on his woman. Nonetheless, the 70mm certainly enhances so many scenes in which Mitch appears: his visit to Deborah Shaughnessy's tombstone, its newly etched inscription sharpened by larger negative, is a poignant close-up. The significant moment when Charles places his hand on Rose's shoulder, and the subsequent close-up as the music swells - this is fine cinema, enhanced by its being in 70mm. The pan along the bed on the wedding night as Charles climaxes, and the subsequent huge close-up of Rose as she turns to face the camera conclusively prove that 70mm, can be singularly effective in intimate moments - these shots have the essence of greatness in them. Michael's observation of the arrival of Doryan is also remarkable for Lean's direction, but the 70mm process itself aids us to appreciate the actual clarity of Michael's vision (and remember the films original working title was "Michael's Day"). Christopher "Chubasco" Jones may not have the brooding starry presence of the original signed choice Marlon Brando (what a movie it would then have been!), but he's by no means as negligible as contemporary reviews would have you believe. Revoiced (by who, I wonder?) and lit broodingly by Freddie Young (particularly in the overlong scene with Gerald Sim), and with his dialogue kept to a minimum, - its easy to believe in his sexual combustability with Rosy Ryan. Their love making in the glade is extremely sensual, and very daring for the time in what was, after all, a major MGM family epic. (Was the revealed breast in the American prints?). But as so often happens in the film, the good scenes are countermanded by inferior padding, and Charles' beach fantasy of Rosy and Doryan is grotesquely out-of-kilter and miscalculated, as though director Lean felt that his leading actor would not have been capable of informing the audience by dint of performance, a factor simply never true with Mitchum. How clever though. when Charles tips the proof of Rose's infidelity - the grains of sand - from her riding hat, just how marvellously the 70mm enhances this key plot point. Much else in the latter part of the film is magnificent in the larger negative: the ferocious storm sequences, with Leo McKern seeming genuinely distressed; Rosy's nightdress sensually transparent as she runs to greet her lover (lost on television!); the resolution, with Ryan isolated as his daughter is falsely accused of informing, startling in 70mm. Ultimately, though, its sheer length -70mm or not - becomes wearisome, and the important scenes with Doryan on the beach have their impact dissipated by appearing so late in the audience's toleration level that they lose what should have been a cumulative impact, diminishing even the clever cut to Rosy lighting the fire prior to the important off-screen explosion, a cut reminiscent of the 'match' cut from "Lawrence of Arabia", so beloved of Steven Spielberg. However, the subsequent close-up of a Madonna-like Rose as Michael struggles to tell her the impossible is a truly striking image in 70mm. Today, though, electing to play Doryan's self´immolation off-screen seems far too reticent, though perhaps we should not be too surprised when we remember that director Lean made the cinemas greatest-ever study in reticence, "Brief Encounter". But in 1970, after Vietnam and "Easy Rider", reticence in the movies was clearly unwelcome. No masterpiece, but clearly unique, "Ryan's Daughter" never deserved the scorn poured on her; not Rosy Ryan in the story, nor the film itself. Flawed certainly, and in need of half-an-hour (at least) removed from the screenplay in the first place, "Ryan's Daughter" remains a great screen original, and a supreme example of the work of major talents close to the peak of their powers. But what is truly important is that this film was conceived, photographed and exhibited in 70mm. This second viewing, twenty eight years after my first, confirmed to me that it should be screened no other way. Ever. |

Further in 70mm reading: |

| Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 22-01-25 |