Conversations with Olivier Brunet

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Ramon Lamarca, London, England | Date: 6 March 2005 |

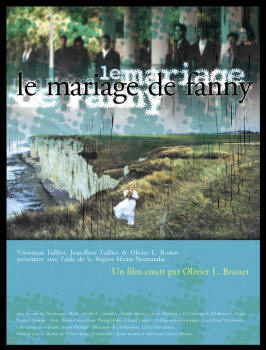

Poster

of the film. Click image to see large version Poster

of the film. Click image to see large versionRead the introduction Ramon Lamarca: The mixture of textures, colours, shades and rhythm in “Fanny’s Wedding” was a very exciting experience. The film managed to pull me into it and I enjoyed its poetic form. The images in 70mm (65mm negative) were gorgeous; to me they brought a sense of peace and serenity. The woman at the end of her life, reflects with that calm so related to old people and the steady and clear image provided by the 65mm negative suggested this to me, together with the use of the landscape, the soundtrack and the editing. Black and white and grainier picture suggested to me past memories difficult to reconcile, the nightmarish figures bending and moving at speeds that belong to the domain of nightmares or sad memories. I love the use of different palettes of colours, formats and techniques in cinema and your short film uses them superbly in a very cinematic and poetic way. I am not familiar with the writers you say influenced your short (although I recognise their names). But even not having read any of the books written by them I felt I could grasp many suggestions from the film, and even not understanding all of it, the very suggestive images were a pleasure to the eyes and the mind. I enjoyed the sound and although I am contrary to the use of pre-recorded music on films (apart from, of course, in the case of source music) I have to admit that your film manages to blend the different compositions in a very original way. |

Further

in 70mm reading: Ramon´s Introduction "Fanny´s Wedding" cast/credit "Fannys Wedding" PDF MCS-70 Superpanorama films Internet link: Various: Olivier Brunet 19 rue Beauséjour 76130 Mont Saint Aignan - France Tel : 33 (0)2 35 98 76 81 Mobile : 33 (0)6 66 80 63 69 |

Mr.

Olivier Brunet: Mr.

Olivier Brunet:Waoo... But you do know everything !! Thank you for this moving account, you really said exactly what I've dreamt people (who would like the film) would say after the screening. It is just that. RL. When was the idea of “Fanny’s Wedding” born? OB. A long, long time ago, back in 1988 as far as I remember. The whole film is the result of a continuous process, it has been "slowly appearing" all through the years, like a picture on photo paper in a darkroom. To cut it short, I was around my thirties (I'm now 44) and seriously considering to slowly move from my job (I was employed as "main titles designer" and special effects supervisor in the parent company of what is well known today as Gulliver, the European 70mm lab in Paris) to full time film making. The question that came first was: "what am I going to talk about, what do I have to say as an author ?" The simplest and most sincere answer was to find out what in my personal background was worth sharing. My childhood, though materially healthy, had been quite sad in my memory. I was shy, lonely, different, quite short and late compared to the other pupils of the same age at school. Isolated. Afraid of everything, first and foremost of experiencing the death of my parents, who where (and are still) believers (Catholics). |

|

I started to write a story about an old man coming back as a "ghost" in the

village where he spent his childhood, not remembering anything but just

knowing he had to come for a wedding. He was to meet an old woman that

eventually proved to be his bride before the war, and also he was to find

his own stone in the graveyard of the village. I started to write a story about an old man coming back as a "ghost" in the

village where he spent his childhood, not remembering anything but just

knowing he had to come for a wedding. He was to meet an old woman that

eventually proved to be his bride before the war, and also he was to find

his own stone in the graveyard of the village.But I also wanted to include some of what my parents, who where teenagers during the Second World War, had told me about their experience. So the ghost became a Jew, who was separated from his wife on the very day of their wedding. In the 6th version of the script, I changed my mind about the main character and decided that it would be the woman and not the (dead) man. The main idea behind the script became: it is possible to enjoy life whatever happens, even the most horrible loss. Fanny discovered slowly that life was possible after Simon's death because of Simon's true legacy to her: his love, and his library. (The books saved my life also, I think, although nobody died in my own family) It took me about 4 years to complete the story and decide how I would put it into pictures. The style of the film (voice over, no actor except for dumb silhouettes, "experimental" mind landscapes) took shape very slowly, as I realised that "my own language" was made of that, instead of traditional film making. The film would be made of 70% "mind landscapes" (memories, modified archive footage, slow motion, grainy black and white mixed with bleach-by-passed colour including choreography, and so on) and 30% "reality", that was to strike the audience with the most colourful and high definition pictures, i.e. 65mm footage! |

|

And at the very end I would mix reality and dreams with the travel of the

little bridesmaid from mind landscape to reality at the top of the cliff. And at the very end I would mix reality and dreams with the travel of the

little bridesmaid from mind landscape to reality at the top of the cliff.I could not find any producer interested in helping me making this film (they all ran scared !!), so with just the help of the lab's directors, Véronique and Jean-René Failliot, a grant from the Normandy Regional Council and my own money, I started shooting in 1996. In the meantime, part of my official job had been to help raise the 70mm lab in Paris. The decision to shoot in 65mm was part of a deal: this would also help the lab to test its equipment at no risk, except to ruin my original negs !! Fortunately all went fine and my dearest dream came true. Though it took more than 4 additional years to complete it, the first 70mm print was released in April 2001, and premiered during the LFCA conference in LA. That's what I think can be called "a labour of love". Sorry, I'm afraid this is quiet long. Next question? RL. Well, ... I can think of many questions after this very complete and interesting answer. Let's perhaps make a technical stop here. You mention that the decision to shoot in 65mm was part of a deal with Gulliver. Did Gulliver propose 65mm to you? or did you propose it to them? If it was your own idea to use 65mm, when did this idea appear in the creation process? OB. Honestly, I've never been able to make up my mind about what actually happened. I do remember that my true wish was to get the biggest possible difference between "reality" and "mind landscapes", in terms of picture quality. I even considered using 35mm 3D for "reality", but not longer than a couple of hours, this idea was impossible ! |

|

Gulliver did not offer anything, I offered the idea (that popped once into

my head) like "Hey, but for God's sake, if I was to shoot my "reality" in

65mm, it would be like test footage for you, so would you help me?" Gulliver did not offer anything, I offered the idea (that popped once into

my head) like "Hey, but for God's sake, if I was to shoot my "reality" in

65mm, it would be like test footage for you, so would you help me?"At this point the idea appeared to be just the best possible for both parts. Then they realised that they would have to blow up the rest of the film as well, and even print down the 65 to scope for the 35mm prints... They've been very helpful and generous, I owe them a lot !! When I started writing, a couple of years earlier, 65mm seemed completely out of hand (far too expensive). It became an opportunity, like a stroke of luck, that sometimes crosses your way, and you may not miss it when it happens. RL. How do the 35mm prints look? I would imagine that "reality" isn't that "real" but that some of the quality of the 65mm negative still permeates, doesn't it? Did you use DTS as well for the 35mm prints? and which prints have got more releases so far, the 70mm or the 35mm? OB. Yes, some of the 65mm quality permeates on the 35mm. However, it would have been barely perceptible except for a professional eye, if I had not cheated. I was aware of the issue, and that's partly why I decided to "bleach-bypass" the "mind landscape" 35mm negative footage, to help "reality" look more real in 35mm as well. I think it works. Nobody can really understand why it looks different, but it does. Anyway, most of the people who really liked the film have seen one of the 70mm print in a good theatre, like the "Max Linder [Panorama]" in Paris. |

|

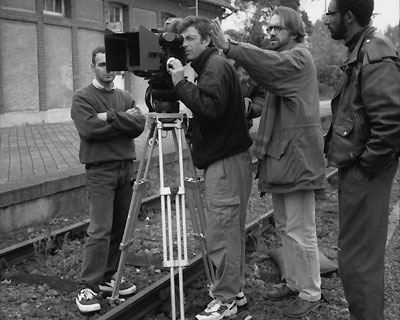

Left

to right, Frédéric Grosso (camera assistant), Vincent Jeannot (director of

photography), Olivier Brunet with a beard and long hair, like he's about to

slap Vincent in the face (!), and Valéry Gaillard, the first assistant. Left

to right, Frédéric Grosso (camera assistant), Vincent Jeannot (director of

photography), Olivier Brunet with a beard and long hair, like he's about to

slap Vincent in the face (!), and Valéry Gaillard, the first assistant.The major problem with the 35mm print is precisely the sound. Yes, I used DTS for 35mm as well, and I realised quite quickly that the sound was easily outshining the 35mm picture in small theatres with good sound systems (especially the orchestral "clusters"). A film like this is very fragile. The chances of actually reaching the heart of the audience are slim, based on a subtle balance between the picture size and quality, and the sound level (and quality too), plus - maybe - the opportunity of a short introducing speech telling what kind of experience this is going to be. I use to say: "Just open your eyes and ears and let go, and do not try to anticipate anything, or understand everything." RL. I completely agree with the balance between image and sound. Many multiplexes have very small screens and powerful sound systems. The surround effects when the cinema has got a small screen just detracts from the image, and the magic of cinema is lost. With the Widescreen Weekend I have rediscovered how good is the distribution of five channels behind the screen in the six magnetic track films, I'd rather have this than three channels behind the screen and multiple surround channels around the auditorium. In Bradford the balance was very good, a pity you could not see it. OB. I also acknowledge all I did wrong. This is more of an essay, sometimes a sort of draft, an experimental attempt to picture my most personal concerns, far from universality, that must be part of any film project I think. I was free to do what I wanted, and I happen to do "the best I could”: the film itself shows the limits of my talent as a film maker. I'm not sure I can do better, less obscure, more universal, I'm not sure I understand the rules of cinema, in terms of construction, pace, legibility of the script. With “Fanny’s Wedding”, I've tried to take advantage of my lacks and turn them into a personal language, but I think I partly failed, and the lacks are still obvious. |

|

Choosing 70mm could have been a way to try to conceal my weaknesses... I

have no true answers to that. I still wonder. I think truth is now in the

eye of the audience. The film does not belong to me anymore. Choosing 70mm could have been a way to try to conceal my weaknesses... I

have no true answers to that. I still wonder. I think truth is now in the

eye of the audience. The film does not belong to me anymore.I've got seven 35mm prints (all DTS), and only three 70mm prints, only one having English subtitles (but it is the most beautiful in terms of colour timing). RL. Well, the 70mm print did look gorgeous in Bradford. I think choosing 70mm was an excellent idea as well as using all the other formats, to me it was a very engaging visual and aural experience. I do not think it shows weakness, on the contrary I perceive Fanny's Wedding as a strong piece of art and a very individual film. I dislike giving away plots to people who have not seen the film, people should see films -as you say- with open eyes and ears with little preconceived ideas. You say that your film is based on the lives and works of Thomas Bernhard, Primo Levi and Marguerite Duras; without giving much away of the plot, could you tell us a little bit about the influence that these writers and their lives have had on your film? OB. When I decided to anchor the plot to History, especially the second world war, I felt the necessity to learn as much as possible about these dark times. I read about one hundred books about WWII, and I discovered many authors, first of all Primo Levi. Primo Levi was Italian and interned in an extermination camp as a Jew (and he came back). His book "If this is a man" is an absolute masterpiece about disaster, suffering, surviving and humanity. Consider whether this is a man, Who labours in the mud Who knows no peace Who fights for a crust of bread Who dies at a yes or a no. Consider whether this is a woman, Without hair or name With no more strength to remember Eyes empty and womb cold As a frog in winter. |

|

|

He stands for me as the incarnation of the word "wisdom" and also the word

"kindness". I only picked one sentence of his to include it into the

narration: "At that time there was no "why"." Simon, in my mind, would have had a lot in common with Primo Levi, except that Simon never returned. Marguerite Duras is NOT one of my favourite novelist, but during the war she experienced the same situation that Fanny was to go through. She had put it into writing in a novel/essay called "The pain". Her husband Robert Antelme (who later wrote another masterpiece about life in the camps, "The human race") was interned in Buchenwald, and she tells how she was desperately waiting for him not knowing whether he was dead or alive (although she was about to leave him after he returned). I picked up one line as well: "a miraculous death, without happening, without form", and some of the mood of the book. Thomas Bernhard is one of my favourite author of all times. His sense of humour hidden behind a misanthropic and violently dark vision of life, his life spent alone in a remote farm in the Austrian Alpes, the "whirling" way of his style (close to my dancers' moves), his energy for survival despite his bad health, well, everything in his life and works has a lot to do with “Fanny’s Wedding”. In a way, I think Fanny could have been a kind of she-Thomas Bernhard. I borrowed him (but not literally this time) a lot of what it is about in the narration, like the feeling towards nature (this despicable nature relentlessly trying to destroy me), children (they grow up, become something else, war criminals... And finally corpses) and curiosity (so far curiosity has kept me alive). The way the words and sentences are put together is mine, the philosophy is his (and I kind of share it). His work is never directly linked to WWII's collateral damages except for a couple of plays, but as an Austrian, he couldn't stop mocking and cursing his fellow-countrymen's cowardice, anti-Semitism and guilt. |

|

The rest is mine, as far as it is possible to say that we own anything when

it comes to words... The rest is mine, as far as it is possible to say that we own anything when

it comes to words...Something else: my dream at once was to make a true English version, and convince Kristin Scott-Thomas who lives in Paris to be the narrator... Unfortunately, I could not afford the recording and remix, and then a new DTS disk, provided that it would have been just for not more than a couple of screenings. RL. I am happy that you did not manage to get Kristin Scott-Thomas. I do not like dubbed films and, although the story of your film could have happened in many countries in Central Europe, I do not think it could have happened in the UK because of its particular circumstances during WWII; this is my perception, and hence the language should be French. It was also conceived in French, and languages have a special beauty. Even if I miss something with the subtitles, there is nothing like real people speaking their real language and the magic sound of the phonetics. And French language in your film fits perfectly, adds beauty and deepness. The only true English version would be a different film, different circumstances, settings, music, scenario, ... OB. I agree, and congratulations for your broad-mindedness. This is also why I have eventually given up (after all I've done, this was just another small mountain to climb). Dominique Blanc's voice is so perfect to me that anything else would have been a loss. But as a part of a "language minority", I was sometimes sad to hear that non-French speakers were disappointed to not understand everything or being frustrated by subtitles "while there is so much to see on the screen"! RL. We have talked about the soundtrack being recorded in DTS, how did you organise the different channels behind the screen and in the auditorium? OB. The most difficult part was to try to set the voice a little in front of the screen rather than behind. I'm not sure I succeeded here, most of all I'm not sure it was such a great idea, but my wish was to let people feel like this voice comes from nowhere, like it was set inside the audience head. I had been struck by one idea in Jane Campion's "The piano", Holly Hunter playing the part of a dumb women whose "mindvoice" is the only thing we can hear. |

|

The idea behind the mix was to fit the different moods (mind landscapes,

dreams, reality) as close as possible sound-wise. On one hand a whirling

sonic storm dispatching the effects all around the theatre, on the other, an

attempt to make nature sound as faithfully as possible from behind the

screen. My use of surround was a little unorthodox, I thought this film was

a good field to try some experiences, especially with multiple layers of

distorted ambient sounds combined with music in a way that would melt them

inextricably. The idea behind the mix was to fit the different moods (mind landscapes,

dreams, reality) as close as possible sound-wise. On one hand a whirling

sonic storm dispatching the effects all around the theatre, on the other, an

attempt to make nature sound as faithfully as possible from behind the

screen. My use of surround was a little unorthodox, I thought this film was

a good field to try some experiences, especially with multiple layers of

distorted ambient sounds combined with music in a way that would melt them

inextricably.Another thing that nobody notices actually, but that was a guideline for the sound edit and mix on the "dream sequences" is the following: In my dreams sometimes I try to get closer to the thing or person I see, and like if I was in front of a large poster, the closer I get the less I can see what the poster shows but more than the four-colour patterns it is made of. This is why I never made close shots, but only large shots and then I would optically blow up a small part of the picture and emphasise nothing but the stock grain instead of revealing the face features of Simon for example, at the beginning of the film. We tried to do the same with the sound mix, make it confused when the camera was getting closer. An idea, more than a convincing result. The first mix took place in January 1998 after a hectic final sound edit week. But I happened to be so disappointed with the result (after a 14 hours mix marathon, the only thing I could afford at once) that I almost gave up the idea of finishing the film. One of the darkest moments of my life... I asked the sound editor and mixer whether they would accept to change a couple of things, they replied there was nothing wrong but me, and I then realised they had not understood what I really wanted from scratch... So I had to wait for another couple of months to gather extra funds, find a new editor and a new sound mixer... I took advantage of the pause to cut about 30 seconds of the original edit, reintroduce lines that the first team had convinced me to cut (the "curiosity & children's" part), and so on, and the new mix took place end of November 1998. Four days in a beautiful (and expensive) location with the French academy award mixer Gérard Lamps, who loved the film and said it had been a great pleasure and honour to mix it (for free) !!! |

|

Section II |

|

RL. I think that one of the qualities I found in your film is that I did not

become aware of the different technical aspects when I saw it (albeit I knew

they were there) and this is a good thing because this means that the

technical tools reach their goal, to express something without becoming too

apparent as to distract from the message. RL. I think that one of the qualities I found in your film is that I did not

become aware of the different technical aspects when I saw it (albeit I knew

they were there) and this is a good thing because this means that the

technical tools reach their goal, to express something without becoming too

apparent as to distract from the message.As you know, this is a website dedicated to 70mm films. I suppose that many of its readers, including myself, would like to know your opinion on your favourite 70mm films (preferably 65mm originated) with an emphasis on the cinematography and the advantages and main differences you find between, let's say, 70mm and 35mm anamorphic and did any cinematographer have an influence on your film (Freddie Young's “Ryan's Daughter” perhaps?) |

|

OB. Ah! You're just hitting the head on the nail! You read my mind, Ramon.

One of the most memorable moments of my life is a screening of “Ryan's

Daughter” at the Kinopanorama in Paris (now closed, unfortunately). I was 28

and all alone in the huge theatre, and then came the storm sequence... OB. Ah! You're just hitting the head on the nail! You read my mind, Ramon.

One of the most memorable moments of my life is a screening of “Ryan's

Daughter” at the Kinopanorama in Paris (now closed, unfortunately). I was 28

and all alone in the huge theatre, and then came the storm sequence...In general, David Lean's way of composing the frame is for sure my major influence. RL. Interesting! and you will also be intrigued to read that I have never seen “Ryan's Daughter”. The reasons are that there wasn't any re-release of the film in Barcelona, the film was probably shown pan and scanned in television (but since a very tender age I have always refused to see any pan and scanned film on telly). They finally showed a letterboxed print but I decided to wait and, perhaps, one day see it properly in 70mm. The BFI has got a print and I might see it either in London or Bradford. However, I have seen several stills of the film and somehow I thought it could have influenced you, nice to read that you enjoyed a "proper" screening of the film so much. |

|

OB. My favourite 70mm film of all time is

"Playtime". Oddly enough, its

aspect ratio is narrower than the standard 1/2.21 of the regular 70mm frame.

For soundtrack reasons (a magnetic revolutionary 8 strips system that

actually never really happened...). OB. My favourite 70mm film of all time is

"Playtime". Oddly enough, its

aspect ratio is narrower than the standard 1/2.21 of the regular 70mm frame.

For soundtrack reasons (a magnetic revolutionary 8 strips system that

actually never really happened...)."Playtime" is a masterpiece to me because its use of 65mm makes 100% perfect sense. The sharpness of the format is dedicated to a multi-layers composition of each shot, including actions happening at several places inside the same frame. The result is that every time you see the film, you discover something new, something you have never seen before in the background, and I have seen it a hundred times. It's at the same time very funny, and a fantastic and prophetic description of the modern world. And directly linked with Masters Chaplin and Keaton. |

|

RL. I agree completely. The film has to be seen in 70mm and on a big screen.

As you say things are discovered every time you see the film and the

choreography of the film makes sense on a big canvas and loses its visual

power on a television (even if it is a Widescreen television!). Many gags

play with the idea of the see-through clarity of those walls of glass; with

70mm you can perceive those reflections that appear on the otherwise

immaculate windows. At the end of the film the idea of using the traffic jam

as a carrousel really works, and it does because of 70mm being able to

portray this sense of movement. I think Blake Edwards took some inspiration

for his film “The Party”, where there are several actions happening at the

same time inside the same frame. As Tati, it also shows the emptiness of

otherwise very crowded spaces. RL. I agree completely. The film has to be seen in 70mm and on a big screen.

As you say things are discovered every time you see the film and the

choreography of the film makes sense on a big canvas and loses its visual

power on a television (even if it is a Widescreen television!). Many gags

play with the idea of the see-through clarity of those walls of glass; with

70mm you can perceive those reflections that appear on the otherwise

immaculate windows. At the end of the film the idea of using the traffic jam

as a carrousel really works, and it does because of 70mm being able to

portray this sense of movement. I think Blake Edwards took some inspiration

for his film “The Party”, where there are several actions happening at the

same time inside the same frame. As Tati, it also shows the emptiness of

otherwise very crowded spaces.OB. Then come "Baraka", "2001 a space odyssey", "Lawrence of Arabia", "Ryan's daughter" (mainly for the storm sequence), "Tron" (for personal reasons that have few to do with the rather poor quality of the picture) and the beautiful "A year along the abandoned road" by my friend Morten. RL. “Baraka” was one of the last films to be shown in 5/70 in Barcelona. I was lucky enough to see the restored print of “Lawrence of Arabia” in one of the best cinemas Barcelona has ever had. The cinema lights started to dim and then there was only light coming from below the curtains that were still closed and the introduction music started to play, after this the curtains started to open to show a magnificent big slightly curved screen and the visual feast started. I remember when “Hamlet” was released in Barcelona only in 35mm. I phoned the cinema to ask if they were showing a 70mm print. The box office did not know what I was talking about and so they put me through the projectionist, who told me that unfortunately it wasn't, with a nostalgic tone he remembered how you could see the grains of sand in “Lawrence of Arabia” in 70mm. I saw “Tron” and “2001” in 70mm at the biggest screen I have ever seen for conventional cinema. The cinema was called Regio Vistarama and was demolished not long ago after having been closed for many years. When I saw “Tron” I was a teenager and I just remember that technically it was quite revolutionary for its time. I would like to see it again in 70mm. I haven't seen it since. And “A year along the abandoned road” is a gorgeous film. I wish Morten keeps producing more films like this or his last IMAX venture. Both Morten's films make great use of the formats. |

|

OB. This list of films says what I enjoy and what makes the big difference

between 35 anamorphic and 65. 65 is sharpness first (and steadiness, and

brightness). The sharpness provides details like no other format can, it's

more of an experience than just a show. Filming in 65 allows you to include

into the frame millions of details throughout the depth of field, making

them close to equal. 65mm is the perfect format for landscapes, and long

shots, including all the action without the help of editing. Close shots in

65 are pretty tricky, but emotionally can be extremely moving, while you can

sometimes count the actual number of hair in the actor's eyebrow. OB. This list of films says what I enjoy and what makes the big difference

between 35 anamorphic and 65. 65 is sharpness first (and steadiness, and

brightness). The sharpness provides details like no other format can, it's

more of an experience than just a show. Filming in 65 allows you to include

into the frame millions of details throughout the depth of field, making

them close to equal. 65mm is the perfect format for landscapes, and long

shots, including all the action without the help of editing. Close shots in

65 are pretty tricky, but emotionally can be extremely moving, while you can

sometimes count the actual number of hair in the actor's eyebrow.I also prefer 1/2.21 rather than 1/2.35. The difference is slim, but it moves the cinematic experience even closer to our natural field of vision as human beings. RL. It is certainly an experience, very enjoyable indeed. Please tell me a bit more about the close shots. Could this problem be overcome shooting the close shots in 35mm anamorphic and printing them on 70mm with the rest of 65mm originated film? OB. The reason why I find the close shots tricky in 70mm is not a technical problem, but has more to do with ethics... or make-up! The sharpness of the picture reveals everything, for instance every little skin (or make-up) defect becomes visible and can become a disturbance, considering the blow-up ratio of the final screening. There is only one 70mm close-shot in "Fanny's Wedding”: the face of the bridesmaid on the cliff. Not as close as my first wish, because you can easily see that the young actress is actually freezing, her cheeks skin is turning rose/red, and she has a little red broken vessel in one eye! This problem does not really exist in 35 anamorphic, the definition is never good enough to become a problem (and most of the time, the IP/IN process has even lowered the picture quality of the average prints that you will see at your next-door theatre). RL. I have to say that I love variety. I like to see films conceived and shot for Academy ratio, I like the VistaVision ratio (in dye transfer Technicolor prints), scope and yes 1/2.21. What I do not like is the Super 35 format, not only because of its poor quality but also because there are up to three different compositions of the frame, trying to please everyone and pleasing no one. OB. Super 35 is not that bad - as far as, I agree 100%, the choice of the frame is made upfront and set to only one aspect ratio -, and it helps you use short lenses proving unworkable in anamorphic. What actually IS bad is the conversion that must be made at the lab to create an anamorphic 35 IN (Internegative) to make the prints. I don't like anamorphic 35mm too much, although I love the ratio (but not as much as the 65 one, like I said), because most of the times, when you go to a movie, the theatre's hypergonar is so bad, so dirty or so wrongly settled, that most of the picture is out of focus. Or the operator - when there's one - has no idea how to settle the focus properly. Not mentioning the steadiness of the projector, almost always terrible. Cinema is a fragile experience. Everything (technically) should always be perfect, and 70mm helps improving the quality. |

|

RL. Please could you explain further why short lenses are unworkable in

anamorphic? RL. Please could you explain further why short lenses are unworkable in

anamorphic?OB. I shot the 35 part of Fanny in Super 35. It's the best way to get the best 65 blow-ups, you do not need to have your picture go through an hypergonar on the optical printer, and it makes a big difference (geometrically, and in terms of definition). Remember, in case of a blow-up, the picture will have gone through two anamorphic lenses in the end: one on the camera while shooting, the other on the optical printer, while making the blow-up 65 IN. You lose a lot doing this way. Also, I knew from scratch that I was going to blow-up the shots, so we have decided (with my DoP) to create a special 2.21 marker to be inserted in the 435 Arriflex camera viewfinder, in order to get the most suitable framing already in 35mm. A little of this framing is lost on the 35mm prints, there is more picture (top and bottom) in 70! RL. I have read that in the overall budget of a film, using 65mm is not that expensive. OB. Theoretically true, but not really. The camera is far more heavier, more expensive, hard to find and service, you need more light, more people, digital post work is not affordable, and almost nobody will have the chance to see your film in its original format... RL. But they could cut the wages of the big stars! By using it more widely also, all these costs could go down. Some cinemas can still screen 70mm. I think this is the most feasible way of bringing the cinema experience back before it goes away completely. I do not like the digital texture, although I can see its benefits. I do not like either the arrogance that many of the digital advocates use dismissing film as an obsolete tool. As a new tool digital is fine, what is wrong is pretending to eliminate all the other visual tools and replace them by digital. Let me put an example, painters would not eliminate techniques like watercolour or oil on canvas because a new one appears. Digital texture is different. Also, digital can be reproduced at home, whereas 70mm cannot. I am not going to pay £9 to see a digital screening in London. I'd rather save and buy a DLP projector to see films at home. With home computers evolving so quickly, by the time (if they do) cinemas switch to digital, their equipment will soon be obsolete. Are they blind? With experiences like slightly curved big screens, 70mm, and proper acoustics they could offer something that cannot be experienced at home. Who is going to pay for a small screen and a digital screening? George Lucas? Many cinemas were equipped to show 70mm during the 60s and 70s and then the studios did not provide them with enough new films to show. I do not want to sound nostalgic or grumpy but certainly the film experience has lost a lot and whilst cinemas are getting smaller, home cinema is getting bigger. Cinema exhibition has been going from bad to worse since the 50s. I used to love going to the cinema, but nowadays I don't. The small multiplexes really depress me and I feel robbed, £9 for a single ticket, for a small screen (with multiplexes you never know where you are going to end up until you are there) bad projection and a sound system that can be recreated at home. OB. Yes, we are part of a dying breed, I'm afraid... RL. Why do you think the visual aspect of cinema has been forgotten if you think it has? OB. TV. RL. Oh yes TV. It has got some qualities of course, but it has never been fit to show cinema. What they are doing now is downgrading the quality of cinemas so when they sell the home cinema products people can say, yes, it looks like the multiplex, a small screen and Digital sound in 5.1! OB. I'm not sure the visual aspect has been forgotten, because I'm not sure the audience has EVER had any kind of true consideration about that aspect (it's more of a "professional" matter), I think the public cares about the plot first, and it has always been this way. But TV, with its square ratio and its poor picture quality has sort of used the audience to accept low picture quality... Now with digital cinema, it's just becoming the average "accepted" standard. I don't care. When I have the chance to set a screening of "Fanny" somewhere, it's always a big event, BECAUSE for the audience it's a great occasion to remember that cinema can be an experience bigger than life and bigger than...TV or even average theatre screenings. RL. Yes, and I would add webcams or even mobile phones to the list of 'corrupters' of images. Why do people want to watch images on a mobile phone is a big mystery to me. But, for how long will we be able to see cinema as it was conceived? |

|

OB. I have to say I love variety like you do. Variety is the key word for

freedom of choice. What has to be preserved and even developed TO DEATH is

variety, in every field, cinema, politics, religion, art... OB. I have to say I love variety like you do. Variety is the key word for

freedom of choice. What has to be preserved and even developed TO DEATH is

variety, in every field, cinema, politics, religion, art...RL. I fear digital is going to kill variety and TV is going to engulf audiovisual arts. However, and being malicious, one of my wildest dreams is going to a digital screening and seeing a frozen image like it happens to a PC, or an error message appearing on the screen asking the projectionist to reset the whole thing. I can imagine being in the middle of Star Wars 24 (by the way shot using digital backgrounds, digital music, digital actors and with no director at all) when Lucas Skywalker discovers that everything that has happened before has been only a dream of C3PO and also that Darth Vader was not his biological father and he is just a farmer in a forgotten galaxy... then the screen frizzes and a notice appears, which reads: your equipment has produced a fatal error and will shut down. It would be like the old times of village cinemas where the print would break or burn and it would take ages to get the projector running again and people would whistle and ask for their money back.... Because digital files also fail, they do. OB. I love your dream about Star Wars 24!! RL. I strongly feel that film is a beautiful tool (albeit more expensive than others) and that pictures produced using film should be preserved for future generations that way (yes, it is expensive, as it is to preserve other art expressions). Digital is good to make this work more available, especially for personal use at home, but public film institutions should help to establish the release of archive prints using film, and preferably a stable colour system like dye transfer Technicolor, always trying to be as close as possible to the original work. Digital screenings of, let’s say, film originated pictures with optical sound, are very odd, since they are not a product of its time (digital enhanced sound and digital screening are completely different to 24 fps and optical sound) and hence we are left with a hybrid that it is not a product of its time nor a product of the present. I am outraged at digital film restorations that claim to sound and look better than the original (this goes against the principles of restoration). OB. I agree 100% with this input. As an ex lab "rat", I know very well what you are talking about. So far, I have never seen any digital screening (of film-originated material) really satisfying my desires as far as the picture is concerned. It's different when you look at something that was actually shot in HD, or even DV. It's a new tool, it has its own advantages, but for God's sake, why should we turn 100% digital in the future ?? Why not consider keeping the best of both worlds? The market answers: it's an industrial issue. The figures (financial profits) are more important than the philosophy (ie, the result on the screen). And that's a shame. RL. Olivier, it has been a great pleasure knowing more about your film “Fanny’s Wedding” and your thoughts on film, especially 70mm. Many thanks for your time. I would love to keep discussing ideas with you but I think at some point we should finish the interview! I am very glad to read that “Fanny’s Wedding” is going to have some screenings in the USA. OB. I'm honoured by your concern, and happy for all this time we've had chatting together across the internet, and I'm sure this will go on, even now that we have decided this interview had to come to an end! "Fanny's Wedding" has just been screened at the Egyptian, soon will be at the Aero, and I'm very glad that the film can go on "living" like this 6 years after its first release (in 35). I told Paul Rayton that his projection booth was the best place I could dream for the print so far, until someone else in the world asks for it, I'll always do my best to help other screenings happen and get the opportunity to talk about it with perfect strangers like you were when I got your first email. To me, a film is first and foremost a means to communication between people who share the same passion, for film, and somewhat, for life itself. |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|