The Earthquaking, Subwoofing Magic of Sensurround |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Marke Bieschke on July 30, 2019. Re-published with permission | Date: 03.06.2020 |

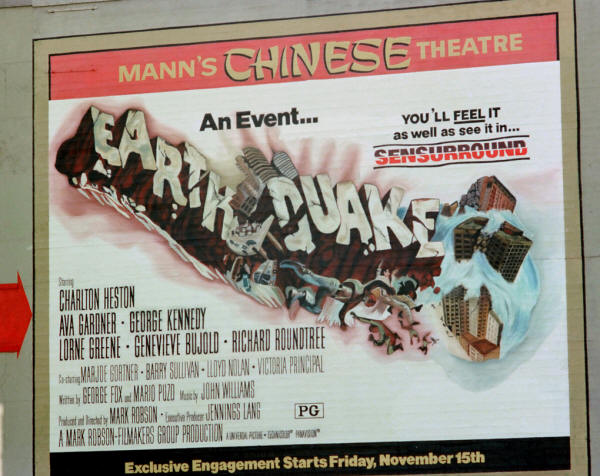

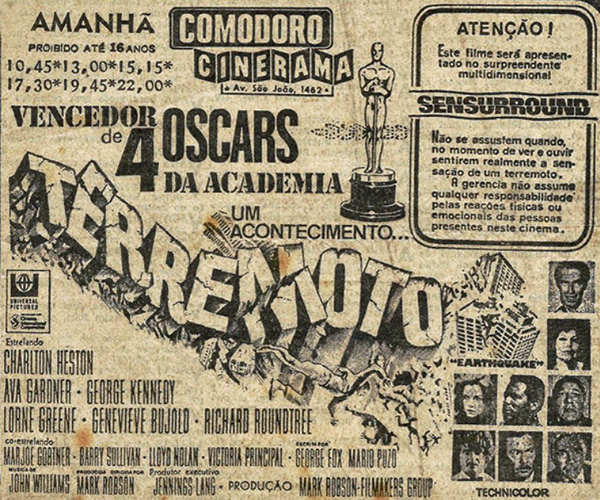

"Earthquake"

in Hollywood, USA.

Photo taken approx. Nov. 6, 1974.

Picture credit: Paul Rayton, Hollywood, USA "Earthquake"

in Hollywood, USA.

Photo taken approx. Nov. 6, 1974.

Picture credit: Paul Rayton, Hollywood, USATwo generations of partiers have felt that clothing-rippling rumble at the rave, the undulating walls of the underground, a festival’s phalanx of whomp. Beyond what you hear from the stacks of speakers, the air seems to vibrate around you. This contemporary bass effect traces itself, beyond any psychotropic symptoms and sound engineering prowess, back to a surprisingly meek source: A teenager huddled under his bedroom desk in early 1970s Los Angeles. • Go to Introduction to Sensurround • Go to About Sensurround • Go to Sensurround Horror Stories That teenager was Rocky Lang, son of famed movie producer Jennings Lang, whose 1974 blockbuster "Earthquake" gave birth to the “SENSURROUND” sound system – and sparked the development of the first widely-used subwoofer design. Sensurround popularized the idea of using sub-audio bass frequencies in theaters and, later, on dancefloors. The Sensurround system’s unique folded-horn speaker design, invented by Gene Czerwinski of Cerwin-Vega, became a staple of the disco craze and has influenced nightclub, concert hall and home theater soundsystems ever since. So how did a star-studded ’70s disaster flick starring Charlton Heston and Ava Gardner lead to today’s floor-melting heaters?

A former executive of MCA/Universal Television who helped pioneer the prime-time made-for-TV movie, Jennings Lang saw the extent to which television and impending recording technologies like the VCR were direct competition to movies. His notion was to turn movies from passive audience entertainments into “events,” drawing people to the theater.

Seeing Rocky curled up on the floor was a eureka moment for his father.

Earthquakes, and disasters in general, were in the air. The recent Sylmar quake

of 1971 that hit San Fernando Valley rocked Los Angeles and killed 64 people.

And Hollywood was heading into the golden age of disaster movies, lavishly

budgeted spectacles that packed in big celebrities – many whose careers were on

the wane – and even bigger special effects. The 1970 movie "Airport", about a

suicidal bomber who attempts to blow-up a Boeing 707 laden with Hollywood

royalty, unexpectedly scored more than $100 million at the box office and ten

Oscar nominations. The race was on to see what major motion picture catastrophe

could next haul in the cash and cachet. |

More in 70mm reading: in70mm.com's SENSURROUND Page - FEEL THE SHAKES Introduction to Sensurround About Sensurround Sensurround Horror Stories Internet link: daily.redbullmusicacademy.com |

Why not an earthquake movie, thought Lang, but one that operated like an

amusement park ride, with a reverberating sound system that could shake the

cinema itself? Theatrical gimmicks were hardly unheard of, from perfume-pumping

1960s special effects like Smell-O-Vision and

AromaRama to schlockmeister

William Castle’s “Percepto!” device, hardwired into theater seats to give

viewers an electrifying jolt during horror flick "The Tingler". Lang’s scheme

would require more technical finesse, however. Most film audio tracks and

theater speakers couldn’t generate frequency signals low enough to give the

quaking effect. Beyond the rumble, too, Lang wanted to devise a system that

enveloped the moviegoer in sound, with speakers placed around the room and cues

on the soundtrack that would transmit certain sounds to certain locations. He

approached the Universal City Studios Sound Department about making Sensurround

a reality. Why not an earthquake movie, thought Lang, but one that operated like an

amusement park ride, with a reverberating sound system that could shake the

cinema itself? Theatrical gimmicks were hardly unheard of, from perfume-pumping

1960s special effects like Smell-O-Vision and

AromaRama to schlockmeister

William Castle’s “Percepto!” device, hardwired into theater seats to give

viewers an electrifying jolt during horror flick "The Tingler". Lang’s scheme

would require more technical finesse, however. Most film audio tracks and

theater speakers couldn’t generate frequency signals low enough to give the

quaking effect. Beyond the rumble, too, Lang wanted to devise a system that

enveloped the moviegoer in sound, with speakers placed around the room and cues

on the soundtrack that would transmit certain sounds to certain locations. He

approached the Universal City Studios Sound Department about making Sensurround

a reality.

Cerwin-Vega was founded in 1954 by aerospace engineer Eugene J. “Gene” Czerwinski, who had an irrepressible drive to expand the qualities of amplified sound. By the early ’70s, his company was already well-known for producing cutting-edge speakers and amplifiers with extraordinary fidelity, and Cerwin-Vega was working with acts like the Rolling Stones and David Bowie on specially designed concert and recording setups.

Perhaps realizing the commercial potential of Sensurround, Czerwinski was the

driving force behind its development, working with Universal’s W.O. Watson,

Richard J. Stumpf and Robert J. Leonard to solve the riddle: how to generate a

sound in the theater so low that no existing speaker could play it? The

specialists experimented on the Universal Studios lot, building huge speaker

cabinets and bringing in test audiences for each attempt to make sure they were

getting the right effect. Watson told American Cinematographer in 1974, “When I

saw the "Earthquake" script I realized that we would be able to come up with a

form of audience participation – something that would make the viewers feel that

they were part of the action that was going on. Our first demonstration was made

using some very high-powered speakers and amplifiers.”

The Sensurround speaker cabinets themselves were enormous and had to be

individually installed in each theater that would play the movie. Entire rows of

seats had to be removed at considerable expense to owners, who risked physical

damage to their buildings. Installation took up to three days and involved a

fleet of inspectors checking for correct electrical specifications and

structural integrity. For the movie’s debut at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in

Hollywood, every inch of the theater, from the basement pipes to overhead

chandelier, had to be inspected and secured. A giant fishnet was spread across

the ceiling to catch any falling plaster. |

|

Nobody knew if

"Earthquake" would be worth it. It was coming out around the same

time as two other disaster films that helped anchor the golden age of genre,

"The

Towering Inferno" and "Airport 1975", and just in the wake of "The Poseidon

Adventure". The studio had spent seven million dollars making the movie, and the

often hammy dialogue and sometimes baffling editing makes it at times hard to

follow, or swallow. The film’s effects are very well-executed – who can resist a

giant tremblor and its aftershocks leveling downtown Los Angeles? – although the

film’s biggest special effect (beyond making us believe that lovely Genevieve

Bujold would fall for leathery Charlton Heston) might be how well Victoria

Principal’s perfectly coiffed two-foot afro survives multiple aftershocks. And

gorgeous set paintings by Albert Whitlock, some old-fashioned scenery-chewing by

Ava Gardner and a score by John Williams that knows to keep quiet during the

fun, quake-y part makes it all enjoyable. Nobody knew if

"Earthquake" would be worth it. It was coming out around the same

time as two other disaster films that helped anchor the golden age of genre,

"The

Towering Inferno" and "Airport 1975", and just in the wake of "The Poseidon

Adventure". The studio had spent seven million dollars making the movie, and the

often hammy dialogue and sometimes baffling editing makes it at times hard to

follow, or swallow. The film’s effects are very well-executed – who can resist a

giant tremblor and its aftershocks leveling downtown Los Angeles? – although the

film’s biggest special effect (beyond making us believe that lovely Genevieve

Bujold would fall for leathery Charlton Heston) might be how well Victoria

Principal’s perfectly coiffed two-foot afro survives multiple aftershocks. And

gorgeous set paintings by Albert Whitlock, some old-fashioned scenery-chewing by

Ava Gardner and a score by John Williams that knows to keep quiet during the

fun, quake-y part makes it all enjoyable.

Luckily for Universal, audiences flocked to the novelty experience despite critics’ misgivings, and cinemas throughout the country rushed to install the special soundsystem. Soon there were 800 systems worldwide, with 400 in the United States. Cerwin-Vega and the Universal Studios team won an Oscar for developing Sensurround, and Earthquake won one for Best Sound. “Sensurround was ridiculed as a noisy, cheesy gimmick by some, but it was truly a stroke of marketing genius – one that delivered sensation both in theater auditoriums and at the box office,” says Dean Lamanna, an entertainment journalist and historian who is working on a book about the disaster film genre.

Sensurround took Europe by storm, too. “I could feel the air move around my

trousers, it was simply staggering,” says Thomas Hauerslev, a former theater

projectionist in Copenhagen who is now an expert in the history of 70mm film. “I

have never experienced cinema sound, or anything like it, since, and that

includes all the fancy digital cinema sound systems with a gazillion loudspeakers

we have today. Sensurround was the ‘mother’ of low frequency in cinemas, and

proved that a real dynamic soundtrack could be added to motion pictures when

most films in those days were either mono, or some variation of four to

six-channel magnetic sound. Sensurround suddenly added an entire new medium to

motion pictures.” |

|

As Sensurround speakers were being torn out of cinemas, versions of them were

filling nightclubs. "Earthquake" had set off a desire for national desire for more

bass, especially on dancefloors during the burgeoning disco craze, and

Cerwin-Vega was happy to fulfill it. Czerwinki’s early folded-horn speakers were

prototypes for the subwoofer, which could deliver more thump in the club.

Legendary club sound engineers Alex Rosner of the Loft and Richard “Dick” Long

of Paradise Garage had come up with their own specialty sub-bass soundsystem

adaptations (Long’s was called the Levan Horn after Larry Levan), to create a

haptic quality where the music could be felt as well as heard. But it was

Czerwinski’s system that was reproduced and marketed quickly. As Sensurround speakers were being torn out of cinemas, versions of them were

filling nightclubs. "Earthquake" had set off a desire for national desire for more

bass, especially on dancefloors during the burgeoning disco craze, and

Cerwin-Vega was happy to fulfill it. Czerwinki’s early folded-horn speakers were

prototypes for the subwoofer, which could deliver more thump in the club.

Legendary club sound engineers Alex Rosner of the Loft and Richard “Dick” Long

of Paradise Garage had come up with their own specialty sub-bass soundsystem

adaptations (Long’s was called the Levan Horn after Larry Levan), to create a

haptic quality where the music could be felt as well as heard. But it was

Czerwinski’s system that was reproduced and marketed quickly.Suddenly, nightclubs had to have “Earthquake bins,” and Cerwin-Vega developed its series “E” subwoofers to fill this demand. “Disco people want to feel the music,” the company’s technical director told Billboard magazine in 1975, “and that takes plenty of clean bass. More clubs are turning to Cerwin-Vega speakers and we’re getting special requests for the identical speakers used for the Sensurround effect used in Earthquake.” And dance music was adapting to these new bass possibilities. 12" records, with wider grooves that prevented needles from skipping as much, were becoming more common, and were being engineered to include more bass volume and lower frequencies. Czerwinski also knew that one way to corner the market during a craze is to spread your ideas around so people can compare. “I think one of the most long-lasting designs that my father came up with was a folded-horn bass,” Connie Czerwinski, Gene’s daughter and former president of Cerwin-Vega, said. “He was famous for it, and it’s one of the designs he gave away to Fender, Acoustic, Sun and Vox. That was our meat and potatoes product for years and years. Where he really shined, he had his own special flair for designing woofers. If you get a JBL next to a Cerwin-Vega, they have a very different sound.” According to the company, Cerwin-Vega’s speaker series “E” remains one of its bestselling of all time. The company still sells folded-horn bass systems called “Earthquake” and “Junior Earthquake,” although neither of them come with Charlton Heston. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |