2013 Widescreen Weekend Introductions |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Feature film text by: Several. Images by: Anders M. Olsson | Date: 26-30.04.2013 |

"The Longest Day" by Sir Christopher Frayling | |

Professor

Sir Christopher Frayling introducing "The Longest Day". Professor

Sir Christopher Frayling introducing "The Longest Day". |

More

in 70mm reading: Widescreen Weekend • Widescreen Weekend 2013 • WSW 2013 gallery Friday • WSW 2013 gallery Saturday • WSW 2013 gallery Sunday • "Audience on Stage" The Making Of The Guns Of Navarone The First In A Major Opus John Wayne Was Set To Play Lawrence Of Arabia Travel to Bradford Past Widescreen Weekend programs Creating the Widescreen Weekend Projecting the Widescreen Weekend Planning the Widescreen Weekend Internet link: |

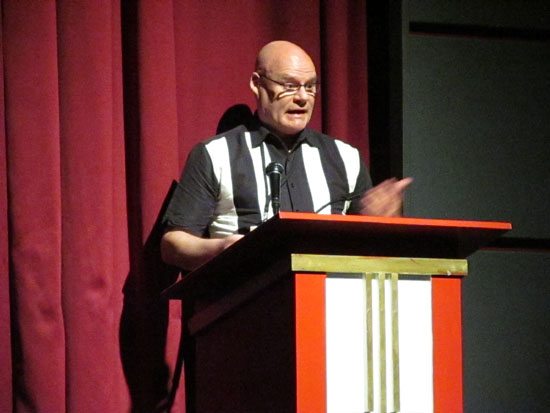

"The Great Escape" by Sheldon Hall | |

Sheldon

Hall introducing "The Great Escape". Sheldon

Hall introducing "The Great Escape".An interesting part of his introduction were two songs; first a "rock video" of the Longest Day theme sung in French by Dalida, then the Great Escape March with the really strange original lyrics performed by Mitch Miller and the Gang. The Great Escape was one of 68 films produced by the Mirisch Corporation for release through United Artists. Mirisch – founded by brothers Harold, Walter and Marvin – was an independent company which became UA’s biggest supplier of product between 1958 and 1974; the film historian Tino Balio, in his book United Artists: the Company That Changed the Film Industry, calls it a “studio without walls”. Among Mirisch’s productions were the Best Picture Oscar winners The Apartment, West Side Story and In the Heat of the Night, and six films produced and directed by John Sturges, including The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and the 70mm Cinerama comedy Western The Hallelujah Trail. The film was budgeted at $2.75 million. Originally only essential locations were planned for shooting in West Germany, with 90% of the production to be made at the Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood (1). Four weeks of location shooting were supposed to begin on 2 April 1962 but were delayed until 4 June, while casting continued until late May. In the end the entire film was made in Germany, the interiors being filmed in the Bavaria Studios at Geiselgasteig near Munich. The first stars to be announced were Steve McQueen, James Garner – and Richard Harris, possibly in the part eventually taken by Richard Attenborough. John Mills was also approached, presumably for James Donald’s role (2). McQueen was also wanted by The Guns of Navarone’s Carl Foreman for his war film The Victors, scheduled to start shooting in September; but The Great Escape overran its shooting schedule by 75% due to bad weather, only completing in October, so McQueen missed out on it (3). Although we now tend to think of The Great Escape as having an ‘all-star’ cast it’s important to remember that this was not how the film was regarded at the time. In its review, American trade paper Variety commented: “Since there are no marquee ‘naturals’ in the cast, this picture will illustrate how superior story and production values can carry a project to great success without the aid of prohibitively expensive, souped-up stellar names. Its [sic] still the picture that counts, not necessarily who’s in it.” (4) Six rewrites were needed for the script, credited to W.R. Burnett and James Clavell – the last version was by Ivan Moffat – which pushed the film further over budget than the weather; it eventually cost $3.8 million, more than $1 million over (5). The rough cut ran five and a half hours, with the aim of being reduced to four; it came in at just under three. Sturges was supposed to go on to direct Yul Brynner in the Mirisches’ The Mound Builders in Mexico immediately afterwards, but was so exhausted that he dropped out, later making The Satan Bug for Mirisch instead. Kings of the Sun, as The Mound Builders was retitled, was taken over by Navarone director J. Lee Thompson. The Great Escape was given its world premiere, in aid of the Royal Air Force Benevolent Association, at London’s Odeon, Leicester Square, on 20 June 1963. The Women’s RAF Auxiliary Band marched the distance from the Air Ministry to Trafalgar Square, playing the title theme; Sturges was so thrilled that he granted the RAF a waiver in perpetuity to play it at concerts (6). Elmer Bernstein’s main title has in recent years become adopted as an alternative national anthem by British football supporters abroad, who can often be heard chanting and humming along to the tune. But how many of them know the original words? There was indeed a title song, with lyrics by Al Stillman, recorded by Mitch Miller and the Singalong Gang, and released as a single on the Columbia label; it was even used in a special trailer and TV spots (7). Here it is. The American opening was in July. The Great Escape ranked eleventh at the US box office among all films opening in 1963, with a good but not outstanding total of $5,545,692 in distributor rentals (8). In Britain however the film was the third or fourth (depending on which source you read) most successful general release of the year, following From Russia with Love and Summer Holiday, and running “neck and neck” with Tom Jones (three of those four were United Artists releases, please note). The general release of The Longest Day, following its roadshow runs, was in fifth place (9). Despite its length, The Great Escape was not a roadshow (there should not be an intermission) and in June 1967 it was reissued in the UK on a double bill with the Mirisch production 633 Squadron. The film also did well in non-English-speaking territories. In France it was number one at the box office, selling over 500,000 tickets in Paris alone (The Longest Day had been number one the previous year) (10). In Japan it grossed $2 million (11). It was the official US entry at the Moscow Film Festival, where Steve McQueen won the award for best male performance (he was also given a prize by the Soviet Union of Sports Societies). Though the film itself was beaten to the top festival prize by Fellini’s 8½, a request was submitted to have it released in the USSR under the Cultural Exchange Agreement (12). The festival had rejected The Longest Day as an unsuitable entry because, according to producer Darryl F. Zanuck, “it did not involve the Soviets in any way and was removed from their interests” (13). Why did they like The Great Escape, then? To British audiences, the film is perhaps best known for its extended afterlife on television. It was shown for the first time on UK TV by BBC1 on 28 December 1971 (the alternative attraction on ITV was the network premiere of another World War Two film, The Train). According to ITV’s Jictar ratings service, the broadcast was seen in 7.1 million homes; the BBC’s own audience research unit estimated the viewing audience as 21.5 million people, making it the most popular programme of the month after the Queen’s Christmas Day message, shown on both major channels (14). The Great Escape has subsequently become a Christmas TV perennial; is it only the British that associate war films with national holidays, I wonder, and what does that say about our national character? I’ll leave the last word to a director who made no fewer than eight films for the Mirisch Company, Billy Wilder, and who said after seeing a preview of The Great Escape: “If Steve McQueen taught Lawrence of Arabia how to ride a motorcycle, he’d be alive today.” (15) |

|

|

1 Daily Variety, 20 February 1962, pp. 1,

4.. 2 Daily Variety, 7 March 1962, p. 2; 18 April 1962, p. 4; 21 May 1962, p. 9. 3 Daily Variety, 27 April 1962, p. 11. 4 Variety, 17 April 1963, p. 6.. 5 Variety, 31 October 1962, p. 24. 6 Daily Variety, 27 June 1963, p. 2. 7 Variety, 5 June 1963, p. 18. 8 Variety, 6 May 1991, p. 96. 9 Kinematograph Weekly, 19 December 1963, p. 5; Motion Picture Herald, 22 January 1964, p. 9; Films and Filming, January 1964, p. 41. 10 Daily Variety, 27 October 1964, p. 126. 11 Variety, 15 July 1964, p. 7. 12 Variety, 31 July 1963, p. 4. 13 Variety, 5 June 1963, p. 3. 14 Western Daily Press, 11 January 1972; Cinema and TV Today, 15 January 1972; Television Mail, 21 January 1972. 15 Daily Variety, 21 May 1963, p. 4. |

|

"The Sound of Music" by Wolfram Hannemann | |

Wolfram

Hanneman introducing "The Sound of Music". Wolfram

Hanneman introducing "The Sound of Music". Good evening, Ladies & Gentlemen, dear Widescreeners, and welcome to our screening of a movie which was selected by BBC executives as one to be broadcast after a nuclear strike, to improve the morale of survivors. A movie which was selected by the United States‘ Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2001 and which was ranked as the #40 Greatest Movie of All Time by the American Film Institute in 2007. A movie which most likely everybody in the audience tonight has seen more than once – Robert Wise’s film version of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s THE SOUND OF MUSIC. It premiered on March 2, 1965, and played in New York for a record-setting 93 weeks. The movie's initial U.S. release lasted 4 1/2 years, and from 1966 to 1972 THE SOUND OF MUSIC was cited by Variety as the "All-Time Box Office Champion." It was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, 5 of which it actually won: Best Director, Best Editing, Best Music Scoring, Best Sound and Best Picture. 1957, two years before the musical made its Broadway debut, Paramount bought the rights to the Von Trapp Singers story, intending to cast Audrey Hepburn as Maria. When Hepburn declined, Paramount dropped plans for a film. In 1960, Twentieth Century-Fox bought the film rights to the musical, along with the rights to two German films about the family from 1956 and 1958. The project was jeopardized by the poor box-office showing of an English dubbed compilation of the German films in 1961, as well as Fox's financial difficulties resulting from CLEOPATRA. After multiple directors had turned down the film, William Wyler finally agreed to take it on. Wyler at the time was suffering from a loss of hearing and was highly sceptical about making a film about music, thinking he was the wrong man for the job. He was slightly appeased in his decision after seeing the Broadway production. However, he actually scouted locations and toyed with the script. He had a different film in mind; tanks crashing through walls, etc. And he wanted Audrey Hepburn to play Maria von Trapp. During pre-production, it was clear to many that William Wyler's heart was not really in it. He was approached midway through pre-production by producers Jud Kinberg and John Kohn who had purchased the film rights to the John Fowles novel 'The Collector' before it had been published. They already had a commitment from Terence Stamp and a first draft screenplay by Stanley Mann. Wyler fell overboard for the script, feeling a much greater affinity with the material than he did with THE SOUND OF MUSIC. Consequently, he asked Darryl F. Zanuck and Richard D. Zanuck to release him from his contract. They agreed. Fortunately, Robert Wise had been experiencing delays with the production of THE SAND PEBBLES and was now at liberty to make the film. Among the actresses considered for the part of Maria were Shirley Jones, Anne Bancroft and Leslie Caron. Doris Day was apparently offered the role, but turned it down. Director Robert Wise then decided to cast Julie Andrews as Maria as soon as he saw “rushes” of her scenes while shooting MARY POPPINS – a part she was given by Walt Disney who was so impressed by Andrews’ Broadway portrayal of Guinevere in Lerner and Loewe’s CAMELOT that he went backstage and asked her to play Mary Poppins. Julie Andrews, by the way, nearly turned down the role of Maria Von Trapp, fearing the character was too similar to her role in Mary Poppins. As soon as Julie Andrews was cast in the movie, attention turned to who would play her Captain von Trapp. Executives at 20th Century Fox were eager for Bing Crosby (a suggestion director Robert Wise never took seriously.) Filmmakers also thought about Sean Connery, Rex Harrison, Richard Burton, Peter Finch, Walter Matthau, and Yul Brynner – known for his star turn in THE KING AND I. The part, of course, went to Christopher Plummer, who opted out of the Harry Palmer role in THE IPCRESS FILE in favor of the Captain Von Trapp part, a decision he later regretted. Plummer’s singing voice is dubbed by professional singer Bill Lee. Among the kids who auditioned to play one of the Von Trapp children were Kurt Russell, Richard Dreyfuss, Veronica Cartwright, and the four eldest Osmond Brothers (Alan Osmond, Jay Osmond, Merrill Osmond, and Wayne Osmond). Liza Minnelli, Patty Duke, Mia Farrow, Kim Darby, Lesley Ann Warren, Tisha Sterling, and Sharon Tate all auditioned for the role of Liesl. Latest news has it that the actor's who portrayed the von Trapp children are planning to be on a cruise, departing on October 5th, 2013. Grace Kelly was considered for the part of the Baroness. However, she had retired from acting when she married Prince Rainier of Monaco and was not open to offers to return to her former profession. So the part went to Eleanor Parker. Fred Astaire was considered for the role of Max Detweiler, which went to Richard Haydn. Marni Nixon became famous as the singing voice of Deborah Kerr in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s film THE KING AND I as well as Audrey Hepburn in MY FAIR LADY and Natalie Wood in WEST SIDE STORY. Nixon finally appeared as a performer on camera while singing the part of Sister Sophia in THE SOUND OF MUSIC. Did you know that the real Maria von Trapp has a cameo appearance in the background in the Residenzplatz during „I Have Confidence“? Dressed in Austrian garb, she is visible for only a fleeting moment, as Julie Andrews sings her story to the cameras. Unaware that filming this short segment would require several takes, Maria later declared „That‘s one ambition I‘m giving up.“ Director Robert Wise and his SOUND OF MUSIC cast and crew wrapped up eleven weeks of shooting on location in and around Salzburg, Austria. The original plan was to shoot in Salzburg for 6 weeks. However, because of continuing rain, they ended up staying in the city for 11. Among the locations they used for shooting was a house owned by actress Hedy Lamarr. Her house became the Von Trapp home. Principla photography resumed in Los Angeles, where Wise shot interiors scenes on sets that included the entire ground floor of the von Trapp villa, the lavish ballroom and the Abbey itself, as filming within the Nonnberg’s walls was forbidden. The film was shot in 65mm Todd-AO by Ted McCord, with the famous opening scene being filmed with a MCS-70 camera. To my knowledge it was McCord’s only 65mm production. Following THE SOUND OF MUSIC he would do just one other film before retiring from business. If you watch very closely you can even spot another famous movie location within THE SOUND OF MUSIC. It is in the background of the picnic in the mountain pasture when Maria and the children start singing "Do Re Mi", where you can dimly make out a castle on top of a hill and I think the 70mm print should reveal it quite good. This castle, called Hohenwerfen, was featured more prominently in the Richard Burton-Clint Eastwood thriller WHERE EAGLES DARE two years later. When the film was originally released in France, the sequences of the nuns singing "Maria" and the Mother Abbess singing "Climb Ev'ry Mountain" were cut as it was felt by the authorities that nuns singing non religious songs was disrespectful. When the film was released in South Korea, it did so much business that some theaters were showing it four and five times a day. One theater owner in Seoul tried to figure out a way to be able to show it even more often, in order to bring in more customers. So he cut out all the musical numbers. My first encounter with THE SOUND OF MUSIC was at the end of the 1970s during one of my first visits to London. During that time the National Film Theatre had a season of 70mm films and they would show two each day. So I was very lucky to attend two of their double features, one being BATTLE OF THE BULGE paired with THE TOWERING INFERNO, the other being CAMELOT paired with THE SOUND OF MUSIC. I learned that the NFT had rented the SOUND OF MUSIC print from the United States, because the only print available in Britain had lost some of its colour. Wow – I never would have imagined that a cinema would go through all that trouble importing a better print from overseas! Not to mention the extra money that had to be spend. Then I thought, well, it is the National Film Theatre which explains everything. But most important: I fell in love with THE SOUND OF MUSIC! What an amazing film. And it really shows off in Todd-AO! Several years later I found out how lucky I was that I had the chance to see this film in its original English version. I discovered that when the film was first released in Germany it was cut down by the distributor, 20th Century Fox, from its original 174 minutes running time to just 127 minutes, eliminating all of the Nazi stuff. I hope that I am not revealing too much of the film’s plot by telling you that the cut version ended with Maria’s wedding! And if that would not have been enough already, this version was completely dubbed into German – including all the songs! What a nightmare! So I guess I am very lucky again, being here tonight in this auditorium, awaiting a screening of the full uncut 70mm print of THE SOUND OF MUSIC in full English language and again, of course, flown in from the United States. |

"Meine Lieder-Meine Träume" in Germany |

"Remnants" by Grant Wakefield | |

Grant

Wakefield introducing his own film "Remnants", a digital time-lapse

extravaganza. Grant

Wakefield introducing his own film "Remnants", a digital time-lapse

extravaganza.Good morning. I’m Grant Wakefield - the director, editor and cinematographer of REMNANTS. The film you’re about to see has been the love of my life, and the bane of my existence, for over two decades! It all began in 1987, as a proposed 10 min. black + white IMAX film that I hoped could accompany a main feature presentation. But five Space Theatre Consortium + Giant Screen Cinema conferences later, and it hadn’t generated the slightest bit of interest. Later it expanded into a 30 minute piece, with a colour section included, but again, nothing…..at which point I began pitching it as a 35mm film. I was very fortunate when Michael Brown of London based Tattooist Productions ran with it for while, but despite his best efforts, the broadcasters, the Arts Council and the like, all passed. That’s when I started thinking about making it myself as a 16mm anamorphic film with clockwork Bolex cameras. But I could barely afford to buy or rent equipment, let alone self-finance a trip around the major Megalithic sites of the British Isles. And so, in about 1995, reluctantly I gave up. At least, I thought I did. Something about the project continued to nag at me. Every once in a while a freelance job, or a holiday, would take me close to a location I hadn’t already scouted. I’d schedule in an extra day or two and photograph it. By 2005 I had close to a hundred. In 2006, a long planned feature project, based largely in Ireland, fell through at the very last minute. A week’s test shoot had been scheduled, and so I decided to go anyway, armed with a single intervalometer, an early Nikon digital SLR and a rudimentary motion control head. Sleeping in the car, and cooking on a stove in the boot, I shot timelapse at as many sites as time and weather would allow. I take a certain amount of delight in the fact that one of these shots has actually made the final cut. From digitised stills, and this Irish timelapse material, the first, proper, full length video-storyboard was born. Paradoxically, when my intention had always been to originate on the highest resolution medium I could, it was the beginning of the end of film that proved to be the turning point. By 2007 I had produced a full treatment and support DVD for a 35 min. IMAX film proposal. And given that so few large format films have ever been produced in the UK, I sent this package out to every IMAX and 8/70 theatre in the country with a heartfelt plea: In a nutshell I said: It looks like film is on the way out. This is probably the last chance for all of us in the UK with a passion for large format to produce a proper 65mm film. Will you get behind this, and help me make it? I received just 3 responses, and their answer was…no. But John Rorke at Birmingham’s ThinkTank Museum suggested that I might try making it in the new digital ‘FullDome’ medium instead. He kindly invited me to come and take a look. And I was impressed. It is, essentially, the digital version of OMNIMAX. And with digital SLR cameras improving almost weekly, I could sense the potential for a high resolution production after all. There I met theatre manager Mario DiMaggio, and he recommended I join FullDome’s Yahoo Discussion list. I duly did, and put out an open call for help with the project. Within 48 hours I received a response from Glenn Smith, managing director of the European division of FullDome planetarium manufacturers and installers SKY-SKAN. With his shared interest in all things Megalithic, he asked for a copy of the treatment, and within just a few weeks I found myself at Stonehenge, shooting test material with a couple of Canon 5D Mk1s. I take more delight in the fact that several of these shots have also made the final cut. But I discovered something problematic immediately. The 180 degree fisheye lenses needed to shoot FullDome were highly limiting in terms of composition, and totally unforgiving in any attempt to hide modern artefacts. One of my principal aims in the film was to capture an ‘ancient essence’ - the feel and possible look of the sites at the time of their construction. But the modern world was everywhere. It would take a team of post-production experts an eternity, and a gigantic amount of money, to paint out the pylons, houses, wires, roads, planes and all the other intrusions that 21st century life comprises. So, early in 2008, we decided to divide the project in two. One half would be a traditional interviewee and narration led documentary, shot with fisheye lenses for the FullDome format, called ANCIENT SKIES. This film would explore the emerging science of Archaeo-Astronomy. A 46 min. version is now complete, and a 25 min. version is in progress. And whilst I was making this film I would, wherever possible, shoot material for REMNANTS with flat lenses, with which I would be able to hide modern artefacts in the frame, and have more control over composition. Which is exactly what happened. So, REMNANTS is essentially ‘the other half’ project, shot whenever the principal cameras were not capturing fisheye material. Fortunately, it’s suffered very little as a result. It’s sad that Thomas Hauerslev isn’t here this year, for it was he that provided the final piece of the puzzle. He forwarded on an innocent e-mail request for information about IMAX DIGITAL to your very own Duncan McGregor here at Pictureville. For reasons I’m still unsure about to this day, Duncan took a look at my on-line work and asked: would I like to show some material at the 2009 Widescreen Weekend event? Yes! I would! And it was the screening of early material at this, and subsequent Widescreen Weekends, that provided the inspiration to plough on. Because I could see that originating in RAW format with Digital SLRs produced an image comparable to 5 perf. 70mm. And this meant my dream of producing a high resolution, experiential large format film was no longer a dream, but a reality. It is thus fitting, and such a tremendous honour, to be here today at Pictureville to show the world premiere of REMNANTS. And I’d like to say a huge thank you first off to: Duncan McGregor and all at Pictureville and the National Media Museum, both for this opportunity, and for your support over the years. And thanks to Alex Hibbitt of Arts Alliance Media, who has also continually supported my efforts with his beautiful digital prints. To Thorsten Quaeschning, for his superb score. To additional cinematographers Lee Ford Parker and Dominic Boudreault, for putting their icing on the cake. To Martin Tarrant for building the camera dolly, and to Bryan Mumford for his super-reliable motion control systems. And to: the amazing Amanda Davis, for digital image cleaning. Where the modern world unavoidably combined with sensor dust, and every flying bug known to humankind, with infinite patience she rescued shots I thought lost to oblivion. And lastly, to project sponsor Glenn Smith, whose trust, faith and generosity made it all possible. Thank you all, so much. And thank you for coming. I hope you enjoy it. |

|

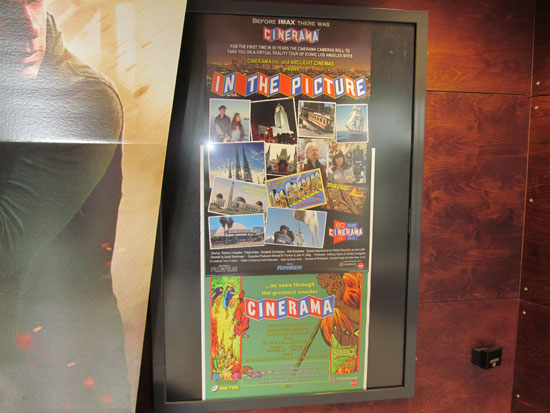

"Seven Wonders of the World" by Randy Gitsch | |

Randy

Gitch lecturing about the difficulties in the making of "Seven Wonders

of the World", and why it was the second Cinerama film to begin

production, but only the third one released. For more details he

suggests reading the diary of Richard J. Pietschmann at in70mm.com. Randy

Gitch lecturing about the difficulties in the making of "Seven Wonders

of the World", and why it was the second Cinerama film to begin

production, but only the third one released. For more details he

suggests reading the diary of Richard J. Pietschmann at in70mm.com.With our team’s digital remastering of the Cinerama 3-panel library of motion pictures, these rarely seen one-time blockbuster road show films have begun to make their retail bow on Flicker Alley DVD and Blu-ray, and can now be screened theatrically from DCP. In 2013 the Cinerama legacy should become more viewable, and more enjoyable to more people, than it has been at any time since the 1960’s. All of this progress, brings us to what are we working on now. The answer is That's Cinerama’s “Seven Wonders of the World”, their 3rd release, from 1956, released here in the U.K., on Feb. 12, 1958. In the U.K., this picture premiered at and played the London Casino theater for 90 consecutive weeks, making it the 3rd most popular Cinerama road show to ever play London. Only “How the West Was Won”, at 123 weeks, and “Cinerama Holiday”, at 105 weeks, beat it. It was also the very last Cinerama picture to play in the mobile Cinerama theater, the Itinerama or the Super Cinerama, as it was called. It’s last show played in Walsall on Nov. 4, 1967. You may have read or heard that “ ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ was the 2nd Cinerama film to start production after ‘This is Cinerama’, but it was the 3rd film released.” That’s absolutely correct. And there’s an interesting story behind “Why?” that happened, which I’d like to share with you this morning. On the eve of the New York City premiere of “This is Cinerama”, on Sept. 30, 1952, no one could have known what a sensational hit it would be. It just might have been a flop. Hence there was no firmly pre-set plan in place to produce any 2nd picture after the first. A plan did develop by the Spring of 1953, however. Keep in mind that as soon as the decision was made to make a 2nd picture, Cinerama needed to evolve as a company. Here’s why. Cinerama was actually, three companies; 1. Vitarama Inc., privately owned by Fred Waller-then his estate and Lawrence Rockefeller, owned the patents to the process; 2. Cinerama Inc., had an exclusive franchise to those patents, under which it made hardware, cameras and projectors. It then sublicensed the right to make films and exhibit them in the Cinerama process to a third entity; 3. Cinerama Productions Corporation made films in Cinerama. This was itself a private company, owned by Lowell Thomas and partners. Cinerama Productions received 75% of the theater profits (the rest went to Cinerama, Inc.), and Cinerama Productions held this exclusive right to license to other producers, allowing them to make films in the process. Up to this time, the man closest to production was Lowell Thomas. He then, and well into the 1970’s, was perhaps the loudest proponent of Cinerama being suited best if not only to outdoor, panoramic reality coverage. Cinerama’s lack of a true close-up ability was cited by Thomas as a reason to stick Cinerama’s future firmly in the travelogue style of story telling. It helps to know that Lowell Thomas was a disciple of Burton Holmes, the popular American lecturer, who himself was an associate of John Lawson Stoddard, the man who coined the word, “travelogue”. Thomas, as a young man, had gotten degrees in oratory, and had taught oratory. And after becoming a journalist and a WWI correspondent, he eventually tagged up with T.E. Lawrence in Jerusalem, and shot film of Lawrence and the Arabs he was helping to up-rise against the Turks. Thomas had then set about presenting in Madison Square Garden and in Covent Garden, then around the world, a hugely successful lecture tour using these film clips. Starting in the 1930’s, Thomas had made his hosted and narrated Movietone News newsreels in the style of miniature travelogues- film clips with narration, before becoming the most famous American radio broadcaster of his time. Certainly, Cinerama, “This is Cinerama” and the two other travelogues Lowell Thomas ended up making for Cinerama, gave him great, audio “close-ups”. If you came from radio, and newsreels, as a travelogue host, hosting Cinerama, in the travelogue style, would have been a wonderful opportunity. Lowell Thomas’s preference for his style of travelogue became well known to the Cinerama management. However, they also harbored an open-minded desire to tackle dramatic content next. Former MGM kingpin, Louis B. Mayer, brought into Cinerama only three weeks after the inaugural premiere to be the Chairman of the Board, in the hope that he’d curry Hollywood studio investment capital, also favored…as it was reported, both fiction and non-fiction for the 2nd Cinerama presentation. Using his name, in January and March, 1953, Variety, the trade paper, made hay of Mayer announcing that “Paint Your Wagon”, which Mayer retained ownership of movie rights to at the time-he’d left MGM, something called “Lawrence of Arabia” and the June 1953, “Coronation of Elizabeth” would be the next Cinerama pictures. As for “Paint Your Wagon”, the Broadway musical of 1951-52, and the West End darling of 1953, it’s interesting to note that in the last week of March 1953, Joseph Schenck, the Chairman of Magna Theatre Corporation had announced that their new Todd-AO process would premiere with “one multi-million dollar musical” which would be road shown in 1954, in approximately 25 specially-selected theaters across the U.S.. This alone may have shied Cinerama away from making a musical in the face of that potential competition from what became the motion picture, “Oklahoma!”. After his being let go from his Cinerama Chairmanship, Mayer continued to try to get “Paint Your Wagon” made into a motion picture, right up to his 1957 death. Even before “This is Cinerama” premiered, in the Spring of 1952, Sir Alexander Korda had traveled to New York and looked at Cinerama test footage, and likely, dailies for “This is Cinerama”, where upon he reached an agreement with Cinerama Production Corp’s pre-curser, Thomas-Todd Productions, to both produce and exhibit Cinerama pictures in England. Variety reported on May 14, 1952, that Korda was ready to begin production on “an outdoor spectacle”. Korda referred to the process as, “…one of the most important inventions in the history of films.” Subsequent reasons given for the failure of these plans were the U.K. government’s disapproval of the necessary royalty payments, and the lack of a single-lens camera.  Randy

Gitch introduces "Cinerama Holiday". Randy

Gitch introduces "Cinerama Holiday".After the appointment of Mayer, the General Manager in Charge of Production for Cinerama Productions Corp., Merian C. Cooper announced that the next Cinerama picture would begin production in 2 months, be produced by himself, and directed by his old friend, John Ford. Nothing came of it. And with Mayer as Board Chairman, no new, 2nd picture was started. This malaise, happening while Cinemascope was premiering, came to be called by Lowell Thomas, writing about it 20 years later, Cinerama’s “fatal delay”. Now you’ll recall I mentioned that IF Cinerama was to go on making pictures, it needed to evolve. This all came to an apparent head in the Spring of ’53. With only three theaters in operation, and each screening all day long to sold out crowds, Cinerama Productions was spending a massive chunk of its’ profits on promotion and operation costs, but needed cash for new productions. Cinerama Inc. needed cash to manufacture more equipment to fit out new theaters, and it needed to finance Smith-Dietrich research into the new single booth modification. The solution was reached in term- licensing exhibition rights to an experienced theater chain, the Stanley-Warner Corporation. Meanwhile pacing in the background, Lowell Thomas had, with the approval of the New York Board of Education, run an essay contest with New York schoolchildren, entitled, “The Story I Would Like to See in Cinerama”. If you’ve ever had a souvenir program for “Seven Wonders” in your hands, you’ll read in it that the ideas behind the picture you’re then about to see came from the suggestions of you, the Cinerama audience. Later today, if you come back for “Cinerama Holiday”, the prologue to that picture features a shot of a large open ledger placed in the theater lobby, in which patrons could write…as the sign said overhead, “What would you like to next see in Cinerama?” Now keep in mind that Lowell Thomas was Cinerama Productions Corp.. To that extent, he was his own boss, and thereby took off with Paul Mantz flying the converted Mitchell B-25 bomber and a camera crew only, including D.P., Harry Squire and his operator, Jack Priestly, and others, spending an amount reported to be at least $500,000 starting “Seven Wonders of the World”. Speaking with Cinerama production veteran Jim Morrison on the phone a couple of months ago, I asked him about this first excursion. Morrison was back in Oyster Bay while the crew was “flying all over hell”, as Jim put it. Jim told me that as a director, Thomas was an ad-libber. He made up their shot sheet in his hotel room and in the plane. If you can’t quite believe that, you might recall Jim’s comments caught in “Cinerama Adventure”, in which he tells of how the “Seven Wonders” crew found themselves eating in a Belgian restaurant in the Congo. When one of the waiters chimed in and said there’s a magnificent active volcano just up the road a couple of hundred miles, Harry Squire, or perhaps Paul Mantz, or likely Lowell Thomas, had said, “By Golly, we’ve gotta’ go and shoot it!” Only Thomas’s approval would have made that happen. And of course, it resulted in one of the greatest shots in all of Cinerama. So being spontaneous can be phenomenally rewarding, but comes at a great price. This may explain why Thomas oddly recalls this first, globe-trotting aerial excursion this way, from his autobiography, So Long Until Tomorrow, ”It seems that I had used up the nearly million-dollar budget for ‘Seven Wonders’ and the picture was still only half finished.” What! They shot 200,000 feet of film, but then, with money tight, and the Stanley-Warner deal under negotiation, filming had stopped. Jim Morrison recalls that the crew ended holed up in a hotel in Cairo perhaps, for nearly a month, withering on the vine waiting for more money to come. It didn’t come, and the crew came home. Merian Cooper had then confidently stepped forward to state that John Ford would step in to direct the “rest of the picture”, which would feature a narrative story line, and which would possibly star John Wayne. As the S-W deal neared signing, the production schedule on the picture had still not been agreed upon. Simon H. Fabian, the President of Stanley-Warner did not want to commit to an extended long-range production program, and was to become contractually bound to produce and finish a Cinerama picture within one year of signing, as well as a 2nd, 3rd and 4th picture by subsequent set dates. Now, at this very juncture, Lowell Thomas offers up an explanation in print, in his last penned book, that I can only describe as “the troubles of the rich”. Thomas, who write of himself as “…a man of money”, with his longtime business partner, Frank Smith, simultaneous to starting “Seven Wonders”, had on the side, just bought an Albany, NY radio and television station, WROW. They had then hoped to upgrade their investment and get the Federal Communications Commission, the “FCC”, to immediately change this station’s ultra high frequency, “UHF” signal into a more powerful, and far-reaching VHF station. In putting that maneuver in motion, Thomas had talked with the head of CBS, Dr. Frank Stanton, to share their desire to also switch their station’s network affiliation from its’ bottom-of-the-barrel ABC programming, to the stronger, more lucrative programming of the tiffany network, CBS. This was all about wanting to broadcast “I Love Lucy” instead of “Wrestling”. All was in place, until the owners of another UHF station in Albany, the one now in line to lose their CBS affiliation, learned of their fate. That station was owned by none other than the Stanley-Warner Corporation. And they promptly brought suit against Lowell Thomas and partners on the grounds that they’d had a prior agreement with CBS when they bought the station. This would have been highly unethical and illegal. Thomas said they hadn’t, and Stanley-Warner lost the case. Consequently, negotiations with Stanley-Warner on whether or not to finish “Seven Wonders”, let alone complete the Cinerama deal at all, were mired in the bad afterburn. On Lincoln’s birthday, Feb. 12, 1955, Thomas’ attorney, Gerald Dickler, who had won the TV station case, and was now, still repping his client, Thomas, sitting idle in the Cinerama case, was confronted by his wife, for whom he’d promised a vacation in Jamaica. “Are we going or aren’t we!”, she’s reported as saying sternly. That prompted him to march into Nat Lapkin’s office, the Stanley-Warner’s Vice President, and, as Lowell tells the story, loudly declare, “ ‘Nat, you can have half a picture and an action against Lowell if that’s what you want. Or you can come up with the additional money and have a completed picture. You decide – I’m going to Jamaica’. And he stalked out.”  By the time the Dickler’s vacation was over, the completion money, an

extra one million dollars, was written into the Cinerama contract. By the time the Dickler’s vacation was over, the completion money, an

extra one million dollars, was written into the Cinerama contract. A proviso required that Thomas complete the picture no later than August 1955. Now, with no previous background in production, Stanley-Warner’s Fabian believed in hiring experts and letting them do their job. Fabian believed in, as Cinerama historian, Thomas Erffmeyer, called it, “…the expertise of autonomous corporate divisions”. This extended to film production. And because of it, Fabian ended up hiring Louis De Rochemont, the American producer/director with a track record of bankable fiction and non-fiction films, to make “Cinerama Holiday”. Started under its’ working title, “The Thrill of Your Life”, De Rochemont had himself brought the story to the deal. De Rochemont wasted no time, and commenced filming shortly after signing in December, 1953. And from the day of his signing, before a frame had been shot…make that three frames, Hollywood trade papers ran headlines stating, “De Rochemont Producing Second Cinerama Feature”. As a hired gun, he completed his picture on time, in June 1954. Although, once edited, the picture sat, waiting for the unexpected longevity of “This is Cinerama’s” box-office power to fade. The whole, reconvened “Seven Wonders” crew, with cameras AND Sound Crew, now fully-funded and re-energized, didn’t fly out of Idylwild for Prestwick, until Sept. 12, 1954. On Feb. 8, 1955, the “Seven Wonders” crew was in Dharan and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia., while “Cinerama Holiday” was finally premiering in Manhattan. You can read soundman Richard Peitschmann’s diary of the journey of the whole crew, as commencing that September, transcribed by Frank Aston, Brian Guckian and Anders Olsson, as appearing right here on in70mm.com “Cinerama Holiday” also enjoyed unexpected box-office power. And so the completed “Seven Wonders of the World”, also sat on the shelf for 8 months. It finally premiered on April 10, 1956, featuring aerial footage shot in 1953, thus becoming the 3rd Cinerama release. And in the U.S., it became the 3rd highest-grossing box-office picture of 1956. And although the picture proved itself another golden goose for Cinerama, the critics began to qualify their accolades. P.S. Harrison, writing in his venerated, exhibitor’s reviewing service newsletter, Harrison’s Reports, wrote of “Seven Wonders”; “Like its predecessors, this third Cinerama production is a hodge-podge travelogue which, despite some sequences which border on the tedious, shapes up on the whole as a vastly entertaining show. There has been no technical advance in the process itself; parts of the picture still appear distorted to those who view it from seats that are off dead center, and the dividing lines between the three pictures that dovetail into one big picture are as “jumpy” as ever. One becomes accustomed to these flaws, however, and they do not seriously affect the entertainment quality. In his 46th of 52 authored books, entitled Seven Wonders of the World, published as a tie in with the movie, Lowell Thomas, who may have then still harbored a desire to maintain his active relationship with Stanley-Warner, simply skimmed over his own history, and wrote; “Meanwhile the exhibition of ‘This is Cinerama’ had been taken over by a newly formed organization called Stanley-Warner, and they produced a second feature, ‘Cinerama Holiday’, after which another picture was needed. So it was that we decided to film the Seven Wonders…” But by the time he wrote, in 1977, his very last book, So Long Until Tomorrow, Thomas, now 85 years old, let more of the truth be told, and wrote in far greater candor the true story of his Cinerama adventure trying to make “the next Cinerama” picture. |

Cinerama Color recovery examples Credits: Cinerama Remastered Cinerama Remaster |

Introduction of "Cinerama Holiday" by Randy Gitsch | |

|

Of all of the 3-panel Cinerama

travelogues, “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” is my favorite. Is it yours? This was the very first picture that I saw in Cinerama, as projected in the New Neon Movies Theater in Dayton, Ohio, in 1996. It was pink, red and magenta…only. I didn’t get the chance to sit back and enjoy the whole movie because I was there making a documentary on film preservation. That particular segment was on John Harvey and how his print of “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” was in fact thee last print of the motion picture, as in last print...on the planet. As a film archivist, that detail hit a nerve in me. That print, as seen in my doc, “KEEPERS OF THE FRAME”, was the same print that some of you may have seen here in Pictureville, when it was shipped over on a 2-year loan. It played here in 2000, the same year that “KEEPERS OF THE FRAME” played in the Cubby Broccoli. So, that year you could have watched “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” here, and then watched a film of people watching it…upstairs. Still on loan, that last print screened here again in 2001. It’s amazing, that a print that looked so awful, so bad, so faded, could still be so powerful, and become so memorable to me, and to some of you. There are some good reasons why that happened. Firstly, unlike “THIS IS CINERAMA”, “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” is one unified story, with a beginning, two middles and an end. And unlike the segmented, “THIS IS CINERAMA”, you’re less inclined to like or hate a single part of it, you either like it all or you don’t, period. It’s “stars”, and I’m going to insist that they are stars, not actors, but stars, are in it from beginning to end and you’ll find yourself empathizing with them. If taken at face value, that you’re watching a Swiss couple, Fred and Beatrice Troller, tour America for the first time, and a couple of American’s, John and Betty Marsh, tour Switzerland and France, for their first time, you’ll start thinking “How different, how unique their albeit scripted adventures must be to them, and how they must be filled with awe, surprise, or wonder.” After all, the Trollers and the Marshes really were traveling out of their respective home countries for the first time. Just one case in point, as late as the year 2000, American Heinz brand tomato ketchup was first sold in a squirt tube with a cap in the U.S.. And initially, U.S. sales spiked because of its’ immediate novelty. For those of you who haven’t seen “CINERAMA HOLIDAY”, you’ll see a ketchup surprise in it. As an American, I’m telling you…it was a real, honest surprise…when this was filmed. “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” is also memorable because of Cinerama, as an effect. Come on, not all of Cinerama’s visual tricks were pulled out of the hat in “THIS IS CINERAMA”. Die-hard film fans will often say that whereas 3-D motion pictures throw something at you, they make you duck. Cinerama pictures pull you in. In my case, the best Cinerama effects make me move my head. So as I watch the Atom Smasher coaster go up, up, up its’ ascent in “THIS IS CINERAMA”, my head tips backward. Not too much, I don’t want people in a darkened theater to notice. In “CINERAMA HOLIDAY”, I’m on that bobsled, and in that icy run, I feel those G-forces as my head is tipping from side-to-side on every turn. That’s not the only thrill sequence in the picture, fortunately. While on the Ferris wheel, the bottom of my stomach drops out, I slump into my seat, and my head rocks. I feel vertical movement. I hope you do too. As I mentioned earlier this morning, “THE THRILL OF YOUR LIFE” as was the “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” working title, came about because of its’ director, Louis De Rochemont. He had the story in mind when he sat down with the brand new Stanley-Warner Cinerama management, to discuss making a picture for them. The picture had appeal to Stanley-Warner, because it wasn’t so closely akin to Lowell Thomas’ plans for the more narrowly defined travelogue, “SEVEN WONDERS OF THE WORLD”, that was already in production. Commencing in December 1953, Producer De Rochemont accompanied Philippe De Lacy directing the European sequences with the Marshes, and de Rochemont’s Associate Producer and co-writer, Otis Carney followed Robert Bendick directing the Trollers in their American adventures. “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” has narrative dramatic flourishes, especially in the second half, in the scenes with the Marshes. When we get to the scenes of Art Buchwald visiting them in their Paris hotel room, just stop and take in the picture a moment. You’ll see a dramatic interplay with 3-persons…3-“actors” hitting their marks in a hotel room interior in widescreen. Compare that to the scenes you’ll see tomorrow of Monroe, Grable and Bacall in “HOW TO MARRY A MILLIONAIRE”, in Cinemascope. 3-actors are hitting their marks in an apartment interior in widescreen. At this point, I think it’s fair to say that Cinerama hits its’ adolescence. There are many spots in “CINERAMA HOLIDAY”, which merit a little background. I’m going to just mention a couple of things I think you’ll appreciate knowing. When the Marshes arrive in Switzerland, via the returning DC-6 that had brought the Trollers to Kansas City at the start of the film, they then train to St. Moritz, to be entertained at the Suvretta House. Built in 1912 in the Belle Époque style, it was a grand hotel destination for the rich and famous, and has been ever since. On the day that the “Holiday on Ice” show was photographed here, it was 10 degrees below zero, and the musician’s lips were sticking to their instruments. The legendary Frick & Frack Swiss comedy skating team had been a part of the American version of “Holiday on Ice” since 1937, and you’ll see skaters performing their well-known moves here, including Frick’s “cantilever spread-eagle” and Frack’s “rubber legs” routine. However, as Hans Mauch, the “Frack” retired in 1953, I have to think we’re watching his understudy or protégé here. The Frick may be the one and only original, Werner Groebli, in which case the Frack should be his then-new skating partner, David Thomas. These performers are not credited. Seven separate bobsled runs were made in St. Moritz. It was so cold that during these runs, the film broke six times. One camera cracked up in a spill. With 1948 Italian Winter Olympic Gold Medal skeleton champion Nino Bibbia at the controls, the very last run set a world speed record, by just 1 minute and 25.3 seconds. Nino’s still alive and turned 91 on March 15. The mass skiing scenes on the Parsenn ski run in Davos, if you believe what your original “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” program tells you, resulted in more than one casualty. All I can tell you is that it didn’t involve the crew or the camera. We’ll drive down the section of Fremont Street in downtown Las Vegas known as Glitter Gulch because of all of the neon signs. And here Vegas Vic is greeting us. He’s the tall cowboy signage, outlined in neon, installed in 1951, so here…still so new that his arms move, and his recorded greeting intermittently drawls out loud, “Howdy Pardner”. Today, the entire street is covered by a LED display/light show ceiling, rechristened the Fremont Street Experience, and Vic no longer waves or talks. The Painted Desert Room was thee place to dine in Wilbur Clark’s Desert Inn, the 5th of the “original” Vegas resorts and one owned by the Chicago mob. It had, like many Vegas showrooms, an elevated stage and terraced table arrangements to make every one of its’ 450 seats a vantage point. This is where “Ocean’s 11, the original with the “Rat Pack”, was shot in 1960. Howard Hughes eventually lived there, and then simply bought it when the hotel asked him to leave. It is sadly no longer there, as the entire Desert Inn complex, expanded and rebuilt and expanded again, and then really compressed when it was all imploded in 2001. The Wynn Las Vegas is now on this spot While the Stanley-Warner deal was being negotiated, Cinerama needed $150,000 in cash and quickly. Help came from a millionaire real estate mogul/friend of Louis B. Mayer, San Francisco millionaire, Louis Lurie. Lurie owned and lived in the Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Fran. So I wonder, could it have been payback that a scene shot in the Hotel’s tony, “Top Of the Mark” restaurant is featured in “CINERAMA HOLIDAY”? Because Lurie was Mayer’s friend, we can say, that this scene is Mayer’s on-screen contribution to Cinerama. To shoot the Vista Dome shots of the California Zephyr train, each of the tinted plexi-glass windowpanes had to be removed and replaced temporarily with clear glass. Such a shame these trains are now long gone other than surviving here or there in railroad museum, or if you’re lucky, as a part of a special private charter train somewhere. One long-time, purported, rumored star cameo associated with this picture, I must debunk. Smokey Robinson is not a part of The Jolly Bunch Social & Pleasure Club’s funeral processional in New Orleans. Although the young man in a blue suit, about 4th from the end of the procession does bear perhaps, a passing resemblance. Smokey would have been just 14 at the time this was shot, and his bios don’t mention him ever getting out of the Brewster neighborhood of Detroit by that age. Furthermore, his Hollywood manager wouldn’t even return my call on this one. There are many enjoyable and fascinating musical performances in this picture. Just one is Jazz bandleader, cornetist and Dixieland giant, Oscar “Papa” Celestine and his Tuxedo Brass Band performing in the Absinthe House on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, in his only filmed appearance. He had performed before President Eisenhower, and died in December 1954, before “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” was released. The Absinthe House is still open. Early on it was visited by Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde. You’d likely order a Sazerac here, the first American cocktail. And the Dog Who Smokes bistro is still there in Paris as it has been since 1740. So-named because one of its’ first chef’s had a dog who smoked. Let’s go! Try to notice, in the scene in the 2nd half when the Trollers and the Marshes are re-united, and they arrive in front of the Warner Theater in Manhattan, you’ll see a multi-story broadside movie poster on the side of the building across the street advertising MGM’s “Brigadoon”. This shot was originally printed with a diffusion mask filter to prevent you from noticing that broadside. You don’t need to be reminded that there’s any other movie on the planet but this one. By the time ‘CINERAMA HOLIDAY” premiered in the U.S. on Feb. 8, 1955, the 3-D craze had dramatically subsided there, and “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” was advertised with the banner, “Imitations come and go but only Cinerama puts you in the picture.” Surpassed only by “LADY AND TRAMP”, “CINERAMA HOLIDAY” earned $12 million dollars, making it the 2nd highest-grossing American film in 1955. And now, it’s about to prove, I believe, it’s still got it. If I wasn’t in Bradford this Widescreen Weekend, I’d be in the Cinerama Dome for the encore Dome-held TCM Film Festival event there. They are tomorrow, with the attendance of the two surviving cast members Betty Marsh, now Betty York, and Beatrice Troller, screening the digitally re-mastered, recombined and Smileboxed “CINERAMA HOLIDAY“, just like Pictureville is going to do for you…now. Enjoy your holiday! | |

"Hello, Dolly!" by Wolfram Hannemann | |

Wolfram

Hanneman introducing "Hello, Dolly!". Wolfram

Hanneman introducing "Hello, Dolly!".„Achtung! I have an important annoucement to make. After an absence of several years there will return to the Pictureville Cinema tonight the lady who has always had the happiest smile, the warmest heart and the largest appetite in the city of New York – Dolly Levi!“ With these (slightly altered) words from Rudolph Reisenweber, the chief waiter at the Harmonia Gardens restaurant, brilliantly played by Berlin born David Hurst in Gene Kelly’s movie version of HELLO, DOLLY! it is my pleasure to welcome you to this Widescreen Weekend saturday evening event. As some of you may already know HELLO, DOLLY! from 1969 will be the only movie surviving mankind - at least according to Pixar Animation Studios. It is in their 2008 animation movie WALL-E that the main character, a small waste collecting robot who seems to be the only living thing on earth in the near future, constantly watches a worn out VHS copy of HELLO, DOLLY! in his tiny home. If you have seen WALL-E and watched very carefully you might also have noticed that our robot is watching a pan- and scan-version of this movie. And this definitely is a „no go“ for widescreeners like us. Therefore I am very happy that Pictureville is providing the real treatment tonight, showing Barbra Streisand and Walter Matthau on the big curved screen in 70mm and 6-track digital sound. It is interesting to note that UK DVD retailer HMV realized during an analysis of its 3rd quarter figures for 2008 that HELLO, DOLLY! had sold more copies in this period than in all the quarters combined for the previous 10 years. This was put down to the popularity of WALL-E which features clips from HELLO, DOLLY! at several key points. The original Broadway production of HELLO, DOLLY! opened at the St. James Theater on January 16, 1964 and ran for 2844 performances, setting a Broadway longevity record. The movie version was released theatrically by Twentieth Century Fox in 1969 at the trail end of a trend of big-budget musicals with which Fox wanted to duplicate the tremendous success of THE SOUND OF MUSIC in 1965, with DOCTOR DOLITTLE and STAR! being the other two. None of these films came close to repeating THE SOUND OF MUSIC’s success and, subsequently, were blamed for the ruination of many studio balance sheets. Suddenly, the merits of these films were beside the point. The result was that several top studio executives lost their jobs, and the studio itself went into such dire financial straits that it only produced one picture for the entire calendar year of 1970. In truth, Fox would never recoup its losses until a highly successful theatrical reissue of THE SOUND OF MUSIC in early 1973. While some of the musicals deserve their fate of late-night television obscurity, others, like HELLO, DOLLY! do not. The film premiered in New York at the Rivoli Theater on December 16, 1969 and at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles on December 19. Production had wrapped more than a year earlier, but release was significantly delayed for legal reasons. A clause in the 1965 film sale contract specified that the film could not be released until June 1971 or when the show closed on Broadway, whichever came first. In 1969, the show was still running. Eager to release the film to recoup its cost, Fox negotiated and paid an "early release" escape payment to release the film at an estimated $1–2 million dollars. One of the actresses considered for the role of Dolly was Elizabeth Taylor, who was passed on because she couldn't sing. Doris Day and Shirley MacLaine were both briefly considered as well. Carol Channing was never considered for the role because it was felt, despite her Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress in the musical MODERN MILLIE, that she could not carry a film of this stature despite being one of Broadway's top leading ladies. Channing's MILLIE co-star, Julie Andrews, ironically turned the role of Dolly down. During filming, Barbra Streisand as Dolly and Walter Matthau as Horace Vandergelder fought bitterly. He disliked her so intensely that he refused to be around her except when required to do so by the script. I guess this is the reason why their pairing in the film works so perfectly. Matthau is famously quoted as telling Barbra that she "had no more talent than a butterfly's fart". In the final shot Horace kisses Dolly in front of the church. Walter Matthau detested Barbra Streisand so much that he refused to kiss her. To get around this he leaned near her and the camera was positioned so that the angle makes it appear that he kisses her when, in reality, his face was several inches from hers. The set for the Harmonia Gardens filled an entire sound stage at Fox Studios and occupied three levels: a dance floor, a main section that surrounded the dance floor and an upper mezzanine. The Harmonia Gardens sequence took an entire month to shoot. For all of you who have seen THE SOUND OF MUSIC yesterday: in the Harmonia Gardens, the back wall behind the hat-check girl is the wall from the ballroom of the Von Trapps Villa. And the large fountain in the Harmonia Gardens set was reused in THE TOWERING INFERNO. It can be seen in the top floor restaurant. It gets knocked over by the water and kills the bartender played by Gregory Sierra. During the filming of BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID director George Roy Hill heard about the turn-of-the-century New York set constructed for HELLO, DOLLY!. He wanted to use the set to film a brief sequence in which Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid and Etta Place visit the Big Apple. The producers were proprietary about the set, and didn't want it to appear in another movie. 20th Century Fox, however, allowed Hill to take still photographs of his stars Paul Newman, Robert Redford and Katharine Ross on the set, surrounded by the extras (who appear in the old-time, tinted photos as city crowds) which were used in a montage sequence that served as a transition between the U.S. West and Bolivia sections of the movie. Let me tell you about my personal experience with HELLO, DOLLY! It was in the 1990s that I first came across that movie. Not in the cinema, but in my home theatre. Being an laserdisc addict during that time I collected every laserdisc I could get my hands on. American laserdiscs featuring a Dolby Digital audio track were the Rolls Royce of my collection – I just had to have all of them. When Fox Video released HELLO, DOLLY! as one of their widescreen editions with Dolby Digital sound it immediately became part of my collection. Having never seen the film before I was very curious to see this Todd-AO production for the first time on my 4x3 color TV – and was disappointed very much. So I put the disc back into the shelf where it stood untouched for several years. All this changed all by a sudden in 2005 when I came to Bradford to participate in Widescreen Weekend’s tribute to 50 years of Todd-AO. HELLO, DOLLY! was one of the films which were shown with new 70mm prints during that occasion. WOW! I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was like I had never before seen this film. I loved it from the first minute to the last. Not only did I enjoy the film so much, I also thought that this must have been one of the best 70mm prints I ever encountered. I will never forget the spontaneous applause from the audience following the waiters‘ ballet sequence and it will be very interesting to see whether this happens tonight as well. So my personal experience with HELLO, DOLLY! proved once and for all for me that certain movies really need an auditorium like this to showcase their full potential. I am very glad to be here tonight. Please note that due to an error the running time of HELLO, DOLLY! is incorrectly stated as 129 minutes in the festival brochure. Rest assured that we are going to see the full 148 minute version including an intermission. |

See

the video |

"The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm" by Duncan McGregor | |

Duncan

McGregor introducing "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm". Duncan

McGregor introducing "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm". |

|

"How to Marry A Millionaire" by Tony Sloman | |

Tony

Sloman introducing "How to Marry a Millionaire". Tony

Sloman introducing "How to Marry a Millionaire".The fourth of November, 1953: The world premiere of ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’, the first motion picture ever filmed in 20th Century-Fox’s new anamorphic big screen process called CinemaScope, whose 60th anniversary we celebrate this year. ‘Millionaire’ wasn’t the first film shown in CinemaScope: that was ‘The Robe’ which premiered on September 16th, 1953: Head of Fox Darryl Zanuck, in his wisdom, realised that ‘The Robe’ would be a more serious appropriate debut for the CinemaScope process, given its subject matter, than the frivolous ‘Millionaire’, which, although filmed before ‘The Robe’, didn’t open until November 1953, at The Globe and at Loew’s State in New York simultaneously, where it was supported by Disney’s first anamorphic effort, the cartoon ‘Toot, Whistle, Pluck and Boom’, plus a ‘scope Coronation short. Zanuck, as usual, was right to open ‘The Robe’ first, as cinema history proved. Let’s take a moment to talk about that history, before we move on to ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ itself. By 1953, U.S. cinema audiences were dwindling; post-war domestic audiences held enthralled by a new device called tele-vision, and older stars, and a few failed film comedians, were proving hugely successful on the home medium, and hordes of people now stayed at home to watch the likes of Milton Berle, Jackie Gleason, or Red Skelton on their televisions, especially on Saturday nights, that evening once solely reserved for the special treat of going out to the movies. The movies fought back with a huge triple-screen and stereophonic sound process called Cinerama, and, for a while, Cinerama was immensely successful, but its size and its complexity of operation made it hard to travel: audiences had to travel to it, rather than the film to the audience. 3-D was also tried, but the process was virtually sabotaged by inept projection, and the excuse of 3-D glasses causing alleged headaches lead to the process being a flash in the 1952-53 pan, only to resurface successfully very recently in the wake of digital projection, obviating the need to run two projectors in perfect synchronisation in order to achieve the three dimension effect. So if 3-D couldn’t maintain its success back in 1953, what was the answer? Anamorphosis. It is a word of Greek origin – an origin that made it especially attractive to the Greek-born head of 20th Century-Fox, Spyros P. Skouros. Now, 20th Century-Fox owned Movietone News, and a French inventor called Henri Chretien had perfected a camera lens he called a Hypergonar, and had used it experimentally on newsreel shorts. The lens ‘squeezed’ the image anamorphically, changing the screen ratio from 1.33 to 1 (approximately a square) to 2.66 to 1 (vaguely resembling a letter box), and Chretien had presented a paper in Paris on the principle of Anamorphosis as early as 1927, but the film industry had seemed totally disinterested. At least they were in 1927. But in 1952 Spyros Skouros’ attention was brought to Professor Chretien’s lenses, and he sent a 20th Century-Fox representative to France to try to locate Chretien. (Oh, and incidentally, as soon as Warner Bros. heard that Fox’s representative in France was looking for Henri Chretien, Jack Warner initiated his own search for Chretien – after all, Warners had once revolutionised the film industry themselves once before, with a little invention called ‘talking’ pictures):- In November 1952, a full year before ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ premiered, Fox’s Herbert Bragg commissioned Bausch and Lomb to manufacture test anamorphic lenses based on Chretien’s original design – only to discover that Britain’s Rank Organisation had an option on the lenses, due to expire on December 16th. On December 18th, 20th Century-Fox picked up Henri Chretien’s option, and the following day screened short tests for Spyros P. Skouros at the Rex Theatre in Paris. Impressed, Skouros flew to Chretien’s home in Nice, and secured an agreement with him for Fox to use the lenses… And just one day after that agreement had been signed, Jack Warner’s representative Joe Hummel managed to reach Chretien in Nice… Having secured the rights to Chretien’s Hypergonar anamorphic lens, Spyros Skouros instructed studio head Darryl F. Zanuck to use it immediately on Fox’s long-gestating epic ‘The Robe’, which was to star Gregory Peck. But Peck had just walked out of his ‘Robe’ contract, and whilst Fox were searching for an available replacement – who would turn out to be the new young contract star Richard Burton – Zanuck ordered that the new process be first used on the next Nunnally Johnson production, a movie that Johnson was putting together utilising one of Fox’s oldest-ever plots, and one that could benefit from the new process, now renamed CinemaScope, and utilising magnetic stereophonic 6-track sound, with a ratio of 2.55 to 1 with the magnetic track, or 2.33 to 1 where an optical soundtrack would be available in addition to the magnetic striping. And such was Zanuck and Skouros’ confidence in their new motion picture process that cinemas not equipped to play stereophonic CinemaScope would henceforth be denied future 20th Century-Fox product. So there! The ploy worked. In the last quarter of 1953 the first and fourth biggest box office grosses were Fox’s first two CinemaScope movies. ‘The Robe’ was at number one, followed by ‘From Here to Eternity’ and ‘Shane’, with ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ coming in at number four, ahead of Disney’s ‘Peter Pan’ at number 5, which, not so coincidentally, featured an animated Tinker Bell whose attitude and looks owed more than a little to one Miss Marilyn Monroe. ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ was the fourth collaboration for producer Nunnally Johnson and director Jean Negulesco, who had had previous successes together with ‘Three Came Home’, ‘Phone Call from a Stranger’, and ‘The Mudlark’. ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ was to be their most popular and most successful. 20th Century-Fox had had a major success back in 1932 with a movie called ‘The Greeks had a Word for Them’, based on a play called ‘The Greeks had a Word for It’. By Broadway sophisticate Zoe Akins, quite simply a plot about three gold-diggers – played by Madge Evans, Joan Blondell, and Ina Claire – looking for husbands, and it was very successful. (By the way, a young ingénue called Betty Grable appeared in it, playing a small role as a model). Fox remade it six years later, in 1938, only this time they called it ‘Three Blind Mice’, and the girls were Loretta Young, Marjorie Weaver, and Pauline Moore. In the meanwhile, Fox and Zanuck have turned that ingénue from the first version, young Miss Betty Grable, into a star when their own biggest musical star, Alice Faye, became pregnant, and instigated a style of casting which Zanuck would perfect throughout the next two decades: that of co-starring the out-going blonde with the incoming blonde, a line of talent that roughly went: Alice Faye, Betty Grable, June Haver, Marilyn Monroe, Sheree North, and Jayne Mansfield, who would become the last of the great Fox blondes: by the way, the successor to Jayne Mansfield was emphatically not a blonde – Mansfield’s co-star in ‘The Wayward Bus’ was Joan Collins. So – ‘Three Blind Mice’ was remade in 1941 as ‘Moon over Miami’, and starred, yes, Betty Grable (with Carole Landis and Charlotte Greenwood), and was further remade as ‘Three Little Girls in Blue’ in 1946, with June Haver, Vivian Blaine, and Vera-Ellen. So when writer-producer Nunnally Johnson (who you’ve just seen uncredited as Marilyn Monroe’s escort at the ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ premiere) was looking for a new Fox project, he certainly didn’t have to look too far!! Johnson went right back to Zoe Akins source material ‘The Greeks had a word for It’ for his ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ screenplay, and cleverly updated it by incorporating another play called ‘Loco’ by Katherine Albert and Dale Eunson, from which he drew Loco Dempsey, the character played in ‘Millionaire’ by top-billed Betty Grable. But note carefully, only on the actual film’s main title itself is Grable billed over Monroe, which was a contractual requirement in Grable’s contract with Zanuck. On June 3rd 1953 20th Century-Fox issued a press release which stated that ‘Twentieth Century-Fox announced today that the studio and Miss Betty Grable have amicably agreed to end their contract’ : So Grable’s contract with Fox ended as ‘Millionaire’ was shooting. Grable – contractually –has billing over Monroe on the actual screen credit titles, but Marilyn had just scored a monumental success at Fox with ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’ in 1953, and so on all advertising materials, including posters and trailers, from henceforth Marilyn Monroe was billed above Betty Grable, who was, in fact, the contractual star of ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’. And Marilyn took over Grable’s dressing room on the Fox lot. Never before – and never again – would Darryl Zanuck’s blonde replacement policy become so obvious. And in the premiere newsreel that you’ve just seen, Betty Grable was a no-show, claiming that she couldn’t appear without an escort, as her husband bandleader Harry James was on tour. But Marilyn turned up without an escort – you saw her clinging onto the arm of writer-producer Nunnally Johnson; no fool, she. Incidentally – there are three good private jokes about the ‘real’ husbands of the co-stars in ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’: Grable references Harry James by name, Lauren Bacall mentions ‘that guy in ‘The African Queen’’, whilst Marilyn –ever Marilyn – just mentions the title of her last smash hit movie ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’ – ‘nuff said. Incidentally, another private joke was not lost on contemporary audiences – and might be worth recalling today – is that all three co-stars in ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ were, in fact, actually married to millionaires!! Betty Grable was married to America’s hottest bandleader, trumpeter Harry James (they had wed in 1943, Betty being five weeks pregnant!, and were to divorce in 1965). Lauren Bacall, of course, famously married her ‘To Have and Have Not’ co-star Humphrey Bogart in 1945 (you remember ‘If you want me, just whistle’) and remained married until his death in 1957. And Marilyn? She wasn’t actually married whilst ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ was in production, but during its worldwide release she wed the world’s greatest baseball legend Joe di Maggio on 14th January 1954! Dollar Millionaires, all!! ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ was such a big success for Fox that they virtually remade the plot of three women looking for husbands several times – Negulesco himself followed ‘Millionaire’ with an even bigger smash hit with the same theme – called ‘Three Coins in the Fountain’, about three women in Rome; then again with ‘Woman’s World’, ditto, set in New York; less successful with a remake of ‘Three Coins’ set in Spain with a younger crowd called ‘The Pleasure Seekers’; and lastly a more sophisticated trio as he filmed ‘The Best of Everything’. Same plot. If ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ is actually the 4th remake (i.e. 5th time out for the same story) of ‘The Greeks Had a Word for It’ – well, you work it out… Just one more point before we let you wallow in this brand-new CinemaScope print – courtesy of 20th Century-Fox Los Angeles. ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ begins, uniquely, with an on-screen overture. MGM was just about to win an Oscar for the best short subject with their CinemaScope filming of the overture to ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’, consisting only of the score played by the MGM Studio Orchestra, and Zanuck got miffed at this news so he had the first film in CinemaScope also begin similarly – although by opening ‘The Robe’ before ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’, he had lost his historical advantage. As you view today, sixty years on, think of this orchestral overture not just as the overture to ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ – which of course it is – but the overture to 60 years of CinemaScope – 60 years of those Henri Chretien Anamorphic lenses – whether called CinemaScope, Panavision, Technirama or whatever – 60 years young, and here to stay for ever! This overture consists of the great Alfred Newman, multiple Oscar-winner, conducting the 20th Century-Fox Studio Orchestra in his composition ‘Street Scene’ – and if it sounds familiar to you, well it is. Fox used it over and over, most notably as title music to those urban New York-set ‘films noir’, ‘Hot Spot’, ‘The Street With No Name’, ‘The Naked City’, and now, most notably of all, the very first motion picture filmed in the wide screen process known as CinemaScope – Happy 60th Anniversary!: ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’. |

|

"The Guns of Navarone" by Brian Hannan | |

Brian

Hannan signing his books "The Making of The Guns of Navarone" and "The

Making of Lawrence of Arabia". Brian

Hannan signing his books "The Making of The Guns of Navarone" and "The