Waking the Sleeping Giant

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Brian Guckian, Ramon Lamarca Marques and Mike Taylor, with Thomas Hauerslev and Chris O'Kane. First Published in this format in Cinema Technology Magazine December 2009 and March 2010, and in Digital & 65mm: Today’s Technology for Tomorrow’s Cinema 2010. This updated version: February 2011 | Date: 21.02.2011 |

Abstract |

|

|

IN today’s era of digital cinema it may

seem anachronistic to focus on mature film technologies as a basis for

innovation in the related fields of film production and exhibition.

However, simplistic assumptions about the preferences of audiences and

the extent of acceptance and dominance of new technologies belie the

possibility of continuing demand for traditional technologies due to

their unique properties. This Paper questions the dominant belief that digital acquisition and presentation of movie content will entirely supercede motion picture-based film production and exhibition. In particular, it posits a different and innovative approach to large-screen presentation in the cinema, and summarises several related technical proposals The history of technological progress in the entertainment industry is not rigidly linear but moderated to some extent by personal preference. A well-known example is the market for vinyl records. Despite the overwhelming dominance of the compact disc format, and latterly, internet downloads, the market for 7-inch vinyl records accounted for two-thirds of UK singles in 2007, with sales up five-fold in the 5 years preceding[1]. What accounts for this survival of an analogue format that should be obsolete? Vinyl fans cite the warmer, more nuanced sound quality over CDs and MP3 files[2] and appreciate the tangible nature of the medium. Similarly, analogue motion picture film has unique properties that appeal to the viewer in ways which are difficult for digital technology to emulate. For example, in the BKSTS Bernard Happé Memorial Lecture of 2004, The Film Look: Can it Really be Defined?, Peter Swinson FBKS portrayed, with regard to film projection, the relaxing effects of slight motion and interruption of the image on the subconscious of the viewer, allowing them to more readily “believe” what was being presented on screen. He also described key attributes of the random grain structure in the film image that lead to film’s wide latitude, dynamic range and ability to represent very fine tonal gradations. The important phenomenon of Stochastic Resonance – the presence of random noise in an image allowing the brain to resolve more subtle detail and more sharpness – was further explained[3]. These fundamental and positive attributes of motion picture film, and its unique exhibition process (mechanical transport with interruptive shutter), mean that it is incorrect to claim direct equivalence by digital video emulation, no matter how sophisticated such processes might be. The projected “film look”, different to that of digital video, also enhances the difference between home entertainment and theatrical exhibition. If there is still a place for film in today’s cinema environment, then what shape should it take? A common mistake made by sceptical observers is to assume that advocates of film acquisition and projection wish to “roll back progress” and to return to a hypothetical “all-film” world. This fails to acknowledge the complexity and diversity of the tools available for production. A useful analogy is found in the art world, where modern acrylic paints, for example, have not superceded oils or watercolours, but have merely added to an expanding palette of options available to the artist. Likewise in music, the development of electronic instruments of increasing sophistication over the years has not in any way led to the diminution or extinction of their traditional counterparts. |

More

in 70mm reading: See PDF version 65/70mm Workshop Internet link: Cinema 70 mm de volta Webinsider |

Combining High Resolution and the Film Texture: 65mm Production |

|

|

The traditional 65mm format provides a

compelling trajectory for developments in the mature film technology area,

especially as theatrical audiences become more demanding of technical

quality, and as HDTV and Blu-Ray Disc penetrate the home viewing

environment. Cost is regularly cited as a perceived barrier to a revival of the traditional 5-perf 65mm format for big-budget productions. However early research by the 65/70mm Workshop discounted this. For example, a 1992 Variety article on "Far and Away" (filmed in Panavision Super 70)[4] quoted its producer Brian Grazer as stating that the additional cost of shooting the film on 65mm was relatively small at $ 700,000. With a quoted budget of $ 45 million[5], this figure represented just 1.6% of the total cost. The later 1996 release of Kenneth Branagh’s version of "Hamlet", also shot on 65mm, was supported by a promotional brochure published by Kodak Professional Motion Imaging. In the brochure, former Managing Director of Technicolor (UK) Ltd. Bob Crowdey stated: |

|

|

|

Confidential figures for 65mm negative

processing, telecine and 70mm printing obtained by the Workshop from a

leading laboratory in 2007 corroborated these earlier views. Using the more

current figures, the additional cost of shooting on 65mm over regular 35mm

for big-budget films was estimated at between 3% and 5% of the total budget,

including the cost of additional camera and lighting equipment. This did not

include CGI; however the cost of high-resolution effects work is falling,

and there is an argument to be made about re-visiting the crafts of

traditional physical model-making and matte painting [7] as well as the use

of real stunts and real extras. Confidential figures for 65mm negative

processing, telecine and 70mm printing obtained by the Workshop from a

leading laboratory in 2007 corroborated these earlier views. Using the more

current figures, the additional cost of shooting on 65mm over regular 35mm

for big-budget films was estimated at between 3% and 5% of the total budget,

including the cost of additional camera and lighting equipment. This did not

include CGI; however the cost of high-resolution effects work is falling,

and there is an argument to be made about re-visiting the crafts of

traditional physical model-making and matte painting [7] as well as the use

of real stunts and real extras.The development of lightweight camera designs since the early 1990s such as the Arri 765, Panavision’s System 65 and most recently the 3D Consortium / MKBK 65mm camera[8] has greatly helped overcome popular misconceptions about 65mm equipment related to perceived bulk and weight. Perceptions of high cost are further countered by the recent use of the 15/70 IMAX format in "The Dark Knight" (2008) and in "Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen" (2009). A common argument today against producing 5/70 prints is that they are allegedly expensive, yet IMAX prints use three times as much film stock but are deemed worthy of investment, and indeed enjoy considerable box office success across many territories. "Hamlet", being the last commercial release in 65/70 mm, also showed how impressive and beautiful film shot in 65mm and presented in 70mm can look, with both high resolution and a pleasing naturalness that has characterised cinema for more than a century, very different from the digital video look. Due to its larger frame size and versatility, 65mm origination further provides highly persuasive advantages in the emerging HD production and display context. Key to this is its multi-platform release capability that maintains very high quality across a large range of theatrical and home cinema release options.  Click

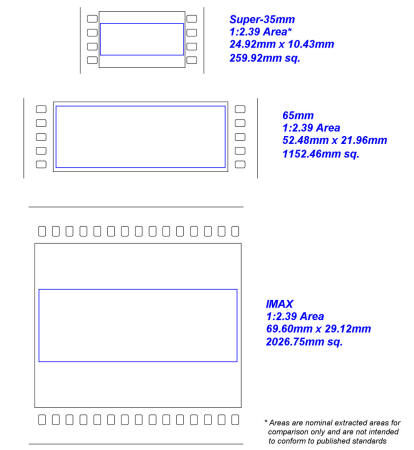

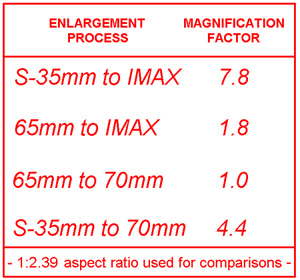

to see enlargement Click

to see enlargementFig. 1 (left) and the accompanying magnification chart show how shooting on 65mm permits straightforward release on the 15/70 IMAX format (with a relatively low magnification factor and theoretically higher quality compared to the current 35mm-based IMAX digital re-mastering [DMR] process), along with the added advantage of being able to make limited quantities of traditional “Roadshow” 5/70 prints (see below). |

|

The 65mm negative also yields far higher quality on conventional 35mm prints

as the negative is over 4 times greater in area (referenced to the 1:2.39

aspect ratio), and critically, also offers an extremely high resolution

source for both 4K and 2K digital cinema platforms (including IMAX Digital),

as well as downstream domestic HDTV transmission and Blu-Ray Disc release.

It is not too surprising that major consumer and professional audio-visual

electronics manufacturers regularly showcase 65mm-originated material to

demonstrate the capability of their display technologies. An example is the

recent Blu-Ray transfer of "Baraka" (originally produced on 65mm, and released

widely in 70mm). The 65mm negative also yields far higher quality on conventional 35mm prints

as the negative is over 4 times greater in area (referenced to the 1:2.39

aspect ratio), and critically, also offers an extremely high resolution

source for both 4K and 2K digital cinema platforms (including IMAX Digital),

as well as downstream domestic HDTV transmission and Blu-Ray Disc release.

It is not too surprising that major consumer and professional audio-visual

electronics manufacturers regularly showcase 65mm-originated material to

demonstrate the capability of their display technologies. An example is the

recent Blu-Ray transfer of "Baraka" (originally produced on 65mm, and released

widely in 70mm). |

|

Click

to see enlargement Click

to see enlargementAcross this wide spectrum of release options, with its ability to offer and maintain very high image quality, plus its important archivability and film-based advantages, 65mm film is a realistic option for visionary filmmakers (Fig 2, left). In addition, the format is “tried and tested” with extant infrastructure and work practices. Non-anamorphic 65mm also offers filmmakers who do not like to work with anamorphic photography the opportunity to have a wide image without having to sacrifice film resolution, as with the current Super-35 format. It is significant that several leading contemporary Directors such as Terrence Malick ("The New World"), Martin Scorsese ("Shutter Island"), Tom Tykwer ("The International") and Christopher Nolan ("Inception") have re-discovered the 65mm format and have used it to various degrees in these recent productions. In an interview with Collider.com, the latter stated: |

|

|

|

“Niche” Distribution |

|

|

On the exhibition front, industry commentators

often wrongly dismiss any possibility of a return to the use of the 5-perf

70mm format by incorrectly assuming that the only distribution model

possible is the former large-scale release practice dating from the 1950s

onwards. Striking several hundred prints is seen to be uneconomic and such

critics further point to the smaller remaining installed base of 70mm

projectors worldwide. Whilst this is true, it fails to consider other distribution methods that might be practical, involve far less cost and which would tailor release to the smaller installed base of 70mm-equipped theatres. In 2008 the Workshop developed a "niche" distribution model that fits in well with a more informed understanding of film exhibition as being diverse and able to accommodate a range of viewing formats simultaneously. As mentioned, a 65mm-originated production can yield limited quantities of 70mm prints. In the contemporary context, the perceived need for "hundreds" of such prints is avoided by re-positioning the 5/70 format as a specialist "showcase" platform for the title in question. In this scenario, only small numbers of prints would need to be struck for a territory, initially for pre-release screenings, using a "Mini-Roadshow" concept previously trialled successfully with conventional 35mm releases in locations such as New York[10]. The Mini-Roadshow concept acts to build excitement and generate word-of-mouth, whilst also permitting higher ticket prices. Typically, the Mini-Roadshow "pre-release" may occur three weeks prior to the normal wide "day-and-date" release. Pre-release screenings on their own are unlikely to justify the striking of 70mm prints, even today with DDE (Datasat Digital Entertainment) sound eliminating the need for magnetic striping. Accordingly, most prints could be crossed over to a new set of locations at the time of the day-and-date release, then crossed over to a subsequent set of venues later, thus maximising the revenue-earning life of the prints. Prints could see further life at 70mm festivals and other special shows, "asset sweating" the investment by the studio / distributor. Additionally, the DDE format readily permits the production of audio tracks for different markets without entailing striking more prints, as well as facilitating electronic projection of subtitles where desired. Designing a limited distribution model for small numbers of 70mm prints made from 65mm-originated material must take account of the fact that studios / distributors are highly unlikely to accede to any additional expenditure on prints, even if such expenditure would be relatively low in the context of typical overall P&A (Prints and Advertising) spend on a major title[11]. However one way of addressing this is to examine where savings could be made in other areas that could offset the small additional cost of striking 70mm prints. Limited 5/70 exhibition is in fact an advantage as it suits the higher quality control, film handling and projection standards both the format and audiences demand. Venues could be accredited, and would not be eligible to receive prints unless they fulfilled a set of accreditation criteria. Comprehensive training could be arranged at cost and allied to the accreditation process. To enhance and protect print life, films should be shown off spools with changeovers. The IMAX release of "The Dark Knight" on 15/70mm showed that audiences appreciate the quality a larger negative with larger prints produces. Neither the film trailers nor the film ads had any mention of the impressive IMAX scenes, yet audiences flocked to the IMAX screenings, even travelling long distances to do so. If audiences value and are voting for the 70mm experience on IMAX screens it can be inferred that 5/70mm should also attract audiences to conventional cinemas with fairly large screens if there is good promotion and marketing of the product. In particular, more mature audiences who are tired of the multiplex experience could return to the cinema if – again – it had a truly theatrical feel. |

|

Compound Curved Screens |

|

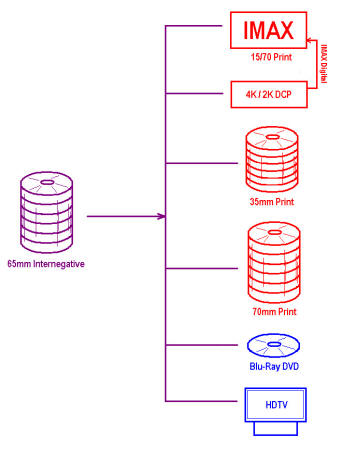

As part of its work, the Workshop has put

forward improvements to the viewing experience, particularly in the context

of the larger image sizes possible with 70mm and with the goal of achieving

greater immersion. As in the past, replicating a sense of peripheral vision

was a key objective. As part of its work, the Workshop has put

forward improvements to the viewing experience, particularly in the context

of the larger image sizes possible with 70mm and with the goal of achieving

greater immersion. As in the past, replicating a sense of peripheral vision

was a key objective.A common technique for curved screens is to use either a chord depth of 5% of the screen width, or to curve to the throw, or to curve via ray tracing according to the requirements of gain screens. Whilst all these methods enhance screen luminance (a common reason for their use today) and provide an aesthetically pleasing curve, they do not offer the immersiveness of former curved screen processes such as those employed by Cinerama, Todd-AO and Dimension 150. With the increasing need to differentiate the cinema experience from the home viewing environment and also to encourage the return - at least on a modest basis - of the "Roadshow" large screen presentation, and further, given the increasing flexibility and attractiveness of shooting on 65mm, the question was asked if former curved screen processes could be revived and adapted for the modern cinema environment. In order to do this, the properties of the two most common immersive "single hole" large screen processes - Todd-AO and Dimension 150 - were studied. Importantly, though effective, both these processes used constant circular curves. This is advantageous for the widest projected aspect ratio, i.e. 2.21:1 or 2.76:1, but narrower ratios are disadvantaged by the same constant curved field. The answer was to "flatten" the central portion of the screen using another, gentler curve. In researching this work, drafting methods showed that a curve of chord depth of 5% of the screen width, combined with the most immersive non-Cinerama curve (120 degrees) to create a compound curve, provided useful results (Fig. 3). Interestingly, use of compound curves was recommended by Philips in the 1960s[12]. In this case they recommended a parabolic curve for multi-format 35mm / 70mm screenings. However it must be noted that the parabola, being an inclined section through a cone, achieves its greatest curvature at its apex. This again goes against the desire for a flatter field for narrower aspect ratios in the central portion of the screen, so that a compound curve of decreasing radius towards the edges rather than the centre appeared to be a better choice of geometric form. The transition point between the two curves was chosen via drafting as the on-screen boundary of the Academy Sound (1:1.37) ratio. There could be a more scientific way of choosing the transition point, but it could also be argued that there is an element of aesthetic choice involved. A fixed transition point was deemed to be necessary if the screen design were to be popularised. Some former curved-screen projection processes required lenses tailored for each venue. However in today's cost-conscious era, such practices are unattractive. A compound curved screen design overcomes the problem by limiting the required correction only to the widest ratios (i.e. 35mm 'Scope, and 70mm), and furthermore, involving only a standard correction method by tying the screen curvature transition to an unchanging point proportional to the screen width. Also, since the curves can be mathematically derived from the screen width, screen size is not a limiting factor. Lenses for the wider ratios could be provided with greater depth of focus to accommodate the deeper curvature towards the screen edges. In 2008 lens manufacturer Isco-Optic GmbH confirmed[13] that the design would work with lenses of 55mm focal length and upwards, and apertures f2.2 and f2.4. A compound curved screen design also greatly minimises cross-reflection as the central portion is flatter and the deeper curved sections are well separated. Screen manufacturer Da-Lite Inc. further recently confirmed[14] that no cross-reflection would occur with this design provided a matt white surface was used. In order to reduce peripheral perceived image distortion on the part of the viewer, seating layouts used with the design would be curved or angled, which in any case is in line with best practice in cinema design. Conveniently, the design would also make it easier to accommodate wider aspect ratios than today's, such as 3:1 Vistamorph. This is because a curved screen design inherently has a shorter linear width for a given ratio than a flat screen does. By extension, this means wider ratios can be accommodated without the need to greatly expand laterally, and thus makes it easier to incorporate such ratios into current cinema auditorium designs that favour "wall-to-wall" flat screens. An important factor in achieving adoption is the standardisation of screen curvature and lens correction. This would keep costs down, and importantly, the multi-format nature of the design and its immersive selling point would be equally attractive for both digital and conventional film screenings. Furthermore, digital 3-D systems which do not require silver screens, such as those from Dolby and more recently, Panavision, could potentially be accommodated by the system. On the production side, use of short focal length lenses more closely matching the viewing angle of the eye, would further enhance a sense of peripheral vision. This of course was a key feature of historical widescreen processes. |

|

9-Channel Lossless Audio |

|

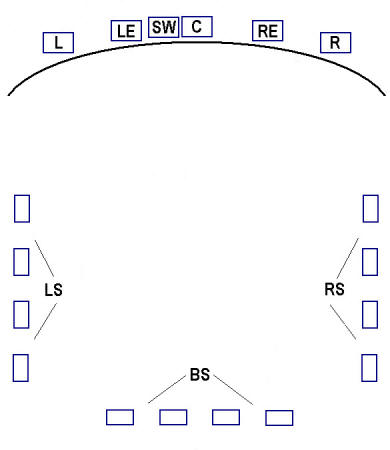

The Workshop also addressed sound reproduction

in the cinema. Here, the objectives were to build on and enhance existing

multi-channel sound techniques in a cost-effective and realistic manner, and

with a greater degree of differentiation to home entertainment formats. The Workshop also addressed sound reproduction

in the cinema. Here, the objectives were to build on and enhance existing

multi-channel sound techniques in a cost-effective and realistic manner, and

with a greater degree of differentiation to home entertainment formats.The conventional 5.1 sound format used in both theatrical and home cinema has been very effective in dramatically improving the audio experience in the cinema and home viewing environments, being refined in recent years with the addition of the back (or rear) surround channel. However, of course 5.1 is not the only multi-channel sound format that has been developed for theatrical use, and in large theatres, the advantages of 5 stage channels, with additional Left Extra and Right Extra information, and a Centre that can be kept free from music and effects, have been known since its advent with Cinerama in 1952. The "5 across" configuration gives better spatial audio experience in large theatres, as the additional Left Extra and Right Extra channels fill the aural "holes" between the Left and Centre and Right and Centre screen channels on very wide screens. The 5 across configuration has also been used on several 35mm SDDS releases over the years, and many cinemas are equipped for this configuration. In 2007 the Workshop proposed, for large screens, a marriage of the traditional 5-across format with the current enhanced 5.1 format with rear surround, to yield Left, Left Extra, Centre, Right Extra, Right, Left Surround, Right Surround, Back Surround and Sub-woofer channels. This gives a total of 8.1, or in short, 9 channels, with several advantages. It was also found that this new 9-channel format could theoretically be accommodated across 70mm, 35mm and D-Cinema digital sound formats, ideal in today's sound post-production and re-recording environment in terms of viability. Lossless audio compression would also ensure highest quality. As many theatres are already equipped for both 5 stage channels and Back Surround playback (the only point to note being that both have not been formally used together up to now), adaptation in these cases to play back 9-channel material does not require new speaker runs, speaker assemblies or amplifiers; rather modifications only at the processor end of the system. It was not within the scope of the work to detail exactly how such upgrades could be done, but merely to point out that it should be possible and was worthy of consideration. 70mm audio and certain 35mm audio formats are theoretically upgradeable to 10-channel reproduction, whilst digital cinema accepts up to 16 channels under DCI[15]. The proposed 9-channel layout is shown for reference in Fig 4 above. Since a 9-channel mix must also be reproducible in a 5.1 theatre, processors would have to include a "fold-down" function so that the Left Extra, Right Extra and Back Surround channels could be mixed into the 5.1 envelope on playback. Alternatively both mixes could possibly be included on discs or hard drives as sent to the cinema. A final consideration was archivability. Fortunately, it is possible to record up to 10 tracks of audio to 35mm fullcoat mag using the specialised "8+2" head and track configuration. This uses 8 sound records across the mag between the perforations, with an additional track outside the perforations on each side. It was concluded that adoption of 9 channels as a new choice for mixing and theatrical reproduction provided the following advantages: |

|

|

|

Marketing: The Premiere Experience Concept and the Return of the Roadshow |

|

|

A critical requirement for 70mm identified by

the Workshop was a relevant, contemporary, effective and well thought-out

marketing strategy. In the modern era marketing has evolved into a sophisticated, semi-scientific, activity based around behavioural psychology and highly-developed data-gathering techniques. Product branding is now a stand-alone discipline and central to effective marketing. In the context of high-quality cinema presentation using 65mm for production and 70mm for exhibition, the challenge was seen as how to update the marketing techniques of the past for contemporary cinema audiences. Considerable creative effort is required in terms of "positioning" the 65/70mm format in today's cinema exhibition environment as a modern, high-quality experience. Key concept elements of a modern 65/70mm marketing strategy were identified as: Quality, Tradition, Spectacle, Theatricality, Contemporary relevance and Exclusivity. One strategy is to focus on the indirect attributes of the format, rather than on its immediate technical characteristics (since in today's world "70mm" does not have the same widespread "brand recognition" that it had in the past). To this end, the brand concept of The Premiere Experience was devised.  The word "Premiere" (US: "Premier") connects with the key concept elements

described above. It evokes images of the 100-year history of the film

industry, an exclusive "red carpet" atmosphere, a high quality theatrical

experience and something of quality and lasting value. The word "Premiere" (US: "Premier") connects with the key concept elements

described above. It evokes images of the 100-year history of the film

industry, an exclusive "red carpet" atmosphere, a high quality theatrical

experience and something of quality and lasting value.A Premiere Experience can be inserted into today's exhibition environment via a physical upgrade to the largest screen or screens in a typical cinema complex, by way of a sub-concept known as the Premiere Screen[16] concept. This also diversifies the cinema experience, in much the same way that modern retail department stores contain discrete sub-units (the "store within a store" concept). Premiere Screens could also be installed at dedicated single-screen cinemas or cinemas with small numbers of screens (for example 3-screen and 4-screen cinemas). Indeed it can be argued that Cinema as an artform and a craft has suffered considerably through the influence of the retail industry and that a de-coupling is desirable via a return to stand-alone cinemas with larger screens and vastly better design. Some effort should be made to bring back some of the imagination of the past and make such cinemas consistent in quality but unique in design and management, accommodating the different patrons’ demands whilst bringing back the sense of excitement that “going to the pictures” had in the past. This of course is dependent on a new economic model being developed that would remove the current "need" for multiple screens, run at low profit margins. An upgrade to the largest screen in a cinema complex - which usually can include a "dormant" 35/70mm projector if the complex was constructed (or split) in the 1990s - could be carried out as a "Premiere Screen" project. The re-vamp of the projection and sound system could be paid for by a small premium on ticket prices. Décor, seating and ambience could also be upgraded, and consideration could be given to significant additional upgrades of the sound system via a loudspeaker baffle wall and greatly enhanced acoustics, which would further support the technical presentation. The interested Exhibitor could go further by installing a compound curved screen to the immersive design discussed above, and Premiere Screens could be certified to guarantee quality of experience. The "Premiere Screen" concept would typically involve just one screen (or for large complexes, two), thus minimising outlay and maximising returns. In large complexes the second screen capability is advantageous in transferring 70mm titles after the initial period of the run. Allied to the wider Premiere Experience concept along with the “Mini-Roadshow” distribution model outlined earlier are the following ideas: 1. Re-introduction of Hard Tickets (tickets at higher prices than normal, with allocated seats, which must be booked in advance, but not to exceed current 3-D ticket prices). This could be coupled with special promotions during weekdays with allocated seats to promote the system and grow audiences 2. Re-introduction of high-quality promotional Brochures which give information on the film, and which can be purchased by the audience at the cinema as collector's items, as stage theatres still do 3. Re-introduction of Trailer Tags, attached to the trailer for the feature film in question and which give release dates and booking details 4. Re-introduction of other Roadshow marketing techniques, including Showmanship in the style of the Todd-AO pioneer and Showman Mike Todd, with use of curtain tabs and full stage lighting. Adverts should be clearly differentiated from the main feature and ideally shown using a smaller screen ratio with curtains just half opened and a simpler and softer sound set-up so as to distinguish it from the film experience. The current practice of showing adverts on a screen larger than that for ‘Scope features (the incorrect “common width” screen configuration) damages the film experience as something unique. Correct screen masking is also essential, and a fine example, compatible with the compound curved screen design described earlier, was installed at the former Odeon Marble Arch cinema in London in conjunction with the Dimension-150 process. This multi-format masking system accommodated all 35mm and 70mm aspect ratios and was an integral part of the D-150 concept 5. New promotional 65/70mm trailers which educate today's audiences regarding the craft aspects of the format, as well as its history. These could be run prior to 70mm feature presentations, in the same manner as conventional sound format trailers, and could comprise short interviews and clips. Similar material could be incorporated into trailers for 65/70mm features themselves. One excellent example is the special 70mm theatrical trailer for Far and Away (1992) where director Ron Howard and producer Brian Grazer explain the unique qualities of the 65mm format to the audience. This could be extended into a new short to promote the 70mm format, like the original The Miracle of Todd-AO 6. Avoidance of cheap concession foodstuffs (Cinerama theatres of the 1950s and 1960s prohibited the selling of popcorn), and their replacement with more sophisticated products like wines and quality confectionery, as found in stage theatres. The Roadshow presentation format facilitates Intermissions that could also increase revenues from sales of such products, and going further, meals could even be served during Intermissions, as has been experimented with in Europe[17] 7. The return of the Roadshow format; something that is belatedly being done for the IMAX release of Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen. Full versions of major films are increasingly only released for the home cinema market, with cinemas having shorter versions, when the contrary should be the norm 8. The return of the Overture - albeit perhaps not as long as it used to be in the 1960s - enhancing a sense of anticipation whilst the lights dim and only the footlights beneath the curtains remain, linked to automatic colour changes to enhance presentation and improve the ambience of the theatre The Rex cinema in Berkhamsted has demonstrated that a return of Showmanship can be successful. Large single-screen cinemas can also reorganise their space to provide for patrons who would like to have a snack whilst watching their favourite movie. The Interval during a Roadshow presentation is the ideal time for some food, which could in some cases be theme-related to the main feature. |

|

Conclusion: Why Should Studios Invest in 65/70mm? |

|

|

65mm film provides a compelling, high quality

origination medium in an era of high-resolution content, offering all the

advantages of film whilst providing a unique multi-platform release

capability. A limited return to 70mm presentation offers exciting new technical advances and marketing opportunities for selected cinemas, with the format re-positioned for specialist showcase / Roadshow screenings. In engineering terms, 70mm is also far more appropriate for many large screens that are currently 35mm / digital only. Piracy has become a serious problem for the industry in recent years with very damaging consequences. Illegal copying or downloading of films is often not perceived as wrongful by the public, and digital technology has made the practice far easier. One solution would be to keep Roadshow 65/70mm films in the photochemical domain only, with no digital versions made available, for the three first weeks of the Roadshow release. With the soundtrack audio on a separate disc, and the film on 70mm reels, a pirate copy may prove difficult to make. Moreover, a 65/70mm production with high production values, and cinematography designed for the big screen rather than the TV screen, would greatly enhance the theatrical experience as compared to that found in the home cinema environment. |

|

The Potential of Vistamorph® in the Cinema Industry

|

|

There

exists today a substantial market for large format cinema. These cinemas

sell the thrill and experience of a big show where films entertain and

educate the audience for 40 minutes with short films and over 2 hours with

commercial feature films. The large format Imax® system has its films

originated on 15-perf 70mm horizontal film. These films are printed and

synced up with a powerful surround sound system. The concept is to convey a

sense of realism to the audience, as if they are physically involved in the

film through the use of scale and power. There

exists today a substantial market for large format cinema. These cinemas

sell the thrill and experience of a big show where films entertain and

educate the audience for 40 minutes with short films and over 2 hours with

commercial feature films. The large format Imax® system has its films

originated on 15-perf 70mm horizontal film. These films are printed and

synced up with a powerful surround sound system. The concept is to convey a

sense of realism to the audience, as if they are physically involved in the

film through the use of scale and power.This idea stems from Cinerama, a system launched on the cinema industry in 1952, where the panoramic film was shown on a curved screen 90ft wide and 30ft high. Accompanied with 7-channel stereo sound, Cinerama made such an impact in the industry that all wide screen film systems were developed as a consequence of the great public response to the Cinerama experience. Even wide screen TV is now the standard in homes. The Vistamorph film system was developed by Vistatech Ltd. as a response to the rising costs of large format film production and presentation in the late 1990’s. It was envisaged that it could fill the role that Cinerama once had in commercial cinema and offer a much lower cost alternative to 15/70 formats as a medium. Vistamorph is a process that can produce spectacular wide screen films and emulates Cinerama in scale. One of the many benefits of Vistamorph is that it utilises existing motion picture technology to produce films at a reasonable cost. Vistamorph has a presentation ratio of 3: 1 to 1 or greater and is originated on 35mm motion picture negative stock. It incorporates a x2 anamorphic optical compression along the horizontal axis of the film stock and is shot in a VistaVision format camera. A range of prime lenses can be coupled to the Vistamorph anamorphic attachment lens for originating wide and medium fields of view.  In

March of 2000 a short test film was shot using a Technicolor model camera

from Panavision and a Nikon prime lens coupled with a x2 anamorphic

attachment. The film was shot in good daylight on Eastman Kodak EXR 50D 35mm

stock. The film A Trip to Dunoon was shot on the west coast of Scotland in

early spring and consists of several shots of moving boats, vehicles and

people in a rural landscape. In

March of 2000 a short test film was shot using a Technicolor model camera

from Panavision and a Nikon prime lens coupled with a x2 anamorphic

attachment. The film was shot in good daylight on Eastman Kodak EXR 50D 35mm

stock. The film A Trip to Dunoon was shot on the west coast of Scotland in

early spring and consists of several shots of moving boats, vehicles and

people in a rural landscape.The film also includes moving camera shots. This was done to test for strobing problems in theatre viewing. These proved to be minimal and non intrusive for the audience. The negative was processed by Technicolor in England and was telecined by The Mill in London. The negative was cut by Trucut of London and a 70mm Vistamorph projection print was produced by Technicolor using existing Technirama printing equipment. The test film was run a DKP75 Kinoton projector with a 3K lamp and shown on a 56ft Todd AO screen where the aspect ratio exceed the width of the screen at 3:1. The film was also test run on the Pictureville Cinerama screen in Bradford and on the 96ft Cinerama screen at the Martin Cinerama Theatre in Seattle, where the aspect ratio of the screen was exceeded also. This was done using a medium focal length backing lens attached to an industry standard x2 anamorphic with a 7K lamp as a light source. The development of better lenses and cameras would further improve the quality of the Vistamorph process and make it a viable system to produce super-wide-screen motion pictures. The costs to do this need not be excessive as some existing equipment could be adapted for the purpose.  The

VistaVision negative format lends itself to fitting in with existing

printing techniques. Fotokem and Gulliver labs can produce either a 70mm or

35mm anamorphic print from the Vistamorph negative. Soho Labs can produce

VistaVision contact prints for VistaVision projection and DDE can produce a

surround sound track for the film. A multiplex cinema could knock two large

halls into a large one and build within it a Vistamorph auditorium that

would allow the screening of, not only Vistamorph 70mm format films, but

also all existing 70mm, 35mm and future digital formats too. The

VistaVision negative format lends itself to fitting in with existing

printing techniques. Fotokem and Gulliver labs can produce either a 70mm or

35mm anamorphic print from the Vistamorph negative. Soho Labs can produce

VistaVision contact prints for VistaVision projection and DDE can produce a

surround sound track for the film. A multiplex cinema could knock two large

halls into a large one and build within it a Vistamorph auditorium that

would allow the screening of, not only Vistamorph 70mm format films, but

also all existing 70mm, 35mm and future digital formats too. |

|

Vistamorph requires at this stage a three-phase development. |

|

|

Phase 1: Production and testing of a full-scale prototype system and test

film. Phase 2: Production of new equipment for filmmaking and the building, or adoption of an existing theatre as a Vistamorph auditorium in a popular location. Phase 3: Establishing the concept worldwide. Vistamorph is a UK registered trade mark - Copyright© Chris O’Kane 2010 |

|

Notes |

|

|

1. Back in the groove: young music fans ditch

downloads and spark vinyl revival, Katie Allen, The Guardian, 16 July 2007 2. Vinyl Gets Its Groove Back, Kristina Dell, Time, 10 January 2008 3. Swinson, Peter, The Film Look: Can it Really be Defined?, Image Technology January / February 2005 pp 17-23, and April 2005 pp 9-12 4. The Future of 65m production is fuzzy, Richard Natale, Variety, 18 May 1992 5. "Far and Away" Test Case for 65mm Film, Screen Digest, June 1992 6. Kenneth Branagh's "Hamlet" on 65mm, Kodak Professional Motion Imaging 7. Filmgoers are sometimes critical of CGI for its lack of realism, as well as misuse of digital effects to the point where there is no suspension of disbelief. There exists a corresponding nostalgia for traditional techniques, which was drawn upon in the recent science-fiction feature film Moon (UK, 2009) in its use of traditional model-making and matte paintings 8. A New 65mm Film Camera, Jonathan Kitzen, www.in70mm.com 9. Christopher Nolan and Emma Thomas interview "Inception" – They Talk 3D, What Kind of Cameras They Used, Pre-Viz, WB, and a Lot More! 10. Is There Any Showmanship Left?, film-tech.com, Film Handler’s Forum, 24 July 2008, p. 3 11. Based on average UK P&A costs of £ 1.8 million quoted in Allison, Deborah, Multiplex programming in the UK: the economics of homogeneity, Screen 2006, Oxford University Press, pp 81-90 12. Planning a Cinema, Philips (Undated, 1960s) 13., 14. Information courtesy AVCOM Ltd., London 15. An interim format that achieves many of the goals of a 9-channel layout is the 8-channel format as previously used by e.g. SDDS and DTS. This comprises 5 stage channels, 2 surrounds and a sub-woofer channel and is not to be confused with the recent Dolby 7.1 format 16. Some cinema chains may already use the term “Premiere Screen”; its use here is purely coincidental and unrelated 17. Communication from International 70mm Publishers, 18 May 2009 |

|

Acknowledgements |

|

|

Thanks to Thomas Hauerslev for his invaluable

input and to Peter Swinson for his kind advice on the text |

|

The 65/70mm Workshop |

|

|

The 65/70mm Workshop

was started in 2006 by projectionist Brian Guckian and 70mm advocate Ramon

Lamarca Marques after a posting on Projectionists’ website www.film-tech.com

calling for a return of the 70mm format to cinemas. Later joined by projectionist Mike Taylor, and supported by Thomas Hauerslev of www.in70mm.com, the Workshop has engaged in research and development of the 65/70mm format and has addressed perceived obstacles to its re-introduction. It has re-positioned the format as a realistic choice for filmmakers, in today’s exhibition environment. Three Workshop sessions were held at the annual Widescreen Weekend in Bradford in 2006, 2007 and 2008, and the Workshop gratefully acknowledges the ongoing and invaluable support of www.in70mm.com and the Widescreen Weekend. |

|

Title Attribution |

|

|

A Sleeping Giant who cannot awake because of the limitations

imposed by the many theatres of restricted potential throughout the world -

a description given to the 70mm format by eminent American projection

engineer Ben Schlanger in 1966 |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|