The Origins of Cinerama | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Mark Trompeteler | Date: 12.06.2013 |

|

As 2012 is

Cinerama’s sixtieth anniversary year and everyone is celebrating

both Cinerama and the huge expansion in widescreen cinematography and

exhibition that followed – it is easy to think in these early years of our

semi automated digital era of Cinema, that everything modern has only

relatively recently been developed. In particular the development of

Cinerama by Fred

Waller has been very widely documented and acknowledged.

However, following attendance at a screening of Abel Gance’s

"Napoleon",

regular CT [Cinema Technology, ed] contributor Mark Trompeteler became curious about some earlier

pioneers in Cinema exhibition and particularly widescreen multi panel

projection systems. | |

Pre–Photography & Cinema | |

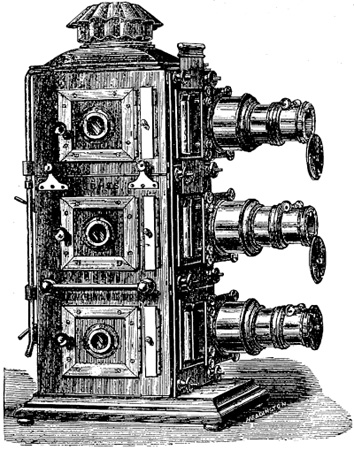

Triple Magic Lantern

Arrangement for Dissolves Triple Magic Lantern

Arrangement for DissolvesSince Cinerama, Cinemascope, Todd-AO, 70 mm, Imax and other large format and widescreen cinema exhibition formats, including higher resolution and brighter digital cinema projectors, screens that almost fill the front wall of a cinema auditorium have become almost a norm in the modern cinema experience. Alarmingly the wonderful aesthetic of widescreen cinematography has been for many years under increasing threat of proper exhibition. This has been caused by increased viewing of films on televisions, computers and other devices, the sheer size of screens that now need considerable masking to show a widescreen film in its proper aspect ratio and the emergence of formats like Digital Imax and their digital re-mastering of films. The acknowledgement by the image creators of the compelling and immersive impact of both large images, panoramic images and curved screens in image exhibition, is something not limited to the cinema image creators of the twentieth and twenty first century. In the Baroque period, in the 17th. and 18th. centuries, during the Restoration period in the UK, and in other earlier centuries, the immersive and compelling impact that huge canvases, very large paintings, and illustrated whole walls as murals or frescoes could have on the viewers, were all clearly understood by painters, their studios and their clients. | More in 70mm reading: Cinerama Birthday 2012. Bradford Celebrates Cinerama’s 60th. Anniversary in70mm.com's Cinerama page The true history of Circlorama 1962-65 “Napoleon in San Francisco” |

Panoramas | |

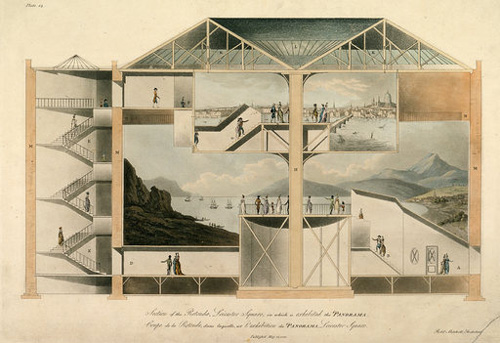

Cross-section of the Rotunda Panorama Building in Leicester Square in which

the panorama of London was exhibited in the smaller “Screen 2“, whilst the

larger “Screen 1” exhibited a huge landscape. (1801) Cross-section of the Rotunda Panorama Building in Leicester Square in which

the panorama of London was exhibited in the smaller “Screen 2“, whilst the

larger “Screen 1” exhibited a huge landscape. (1801)Closer to cinema and Cinerama however was the phenomenon of Panoramas and Dioramas. Panoramic painting became popular in many countries in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1793, a Scottish painter, Robert Barker moved his paintings to the first ever purpose built Panorama building in the world, into the heart of what is now London’s cinema land – Leicester Square. Barker, just as many a modern cinema exhibitor hopes for, made a fortune. Cinema enthusiasts should note that people flocked to queue to enter his Panorama building - they paid a very expensive three shillings admission price to witness the pictorial spectacle. In a Panorama building, patrons entered through foyers, and climbed steps or staircases to viewing areas or platforms where they were able to view huge curved realistic canvases lit carefully to totally immerse the viewer in a visual experience and give them the impression of reality. In Barker’s Panorama Cinerama enthusiasts should note that all borders and joins in the canvas were concealed. Props were strategically positioned so canvas borders or joins could be disguised. The Panorama painter / entrepreneurs were also mindful to give their audiences a good entertainment experience. Their mass audience visual entertainment buildings often used various devices so that the ticket price could often afford the patron viewing two different panoramic paintings. Amidst all the queuing and viewing and use of foyers I wonder if refreshments were on sale too? The cylindrical rotunda type Panorama buildings were built as a form of mass visual entertainment in many cities across Europe and America. In the later stages of sophistication Panoramas gave the illusion of movement by all manner of devices in their visual exhibition of pre-cinema imagery. | |

Dioramas | |

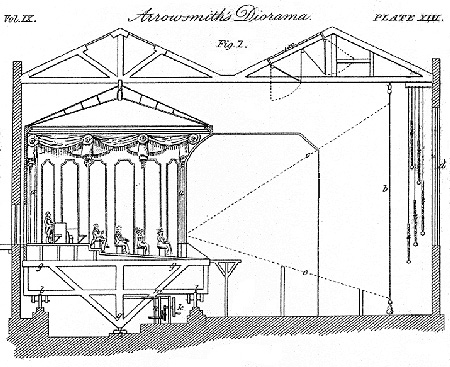

John Arrowsmith's Diorama of 1823 (above) looks remarkably like the concept

of a basic cinema. John Arrowsmith's Diorama of 1823 (above) looks remarkably like the concept

of a basic cinema.Louis Daguerre was a pioneer of photography, but originally he was a decorator, manufacturer of mirrors, painter of Panoramas, and masterly designer and painter of theatrical stage illusions. Prior to his contributions in photography, he developed a variation or an advance on the Panorama building. His Diorama is a worthy pre-historic ancestor to cinema – having virtually every element of the concept of cinema excepting the projecting of film which hadn’t been invented. However he used the picture imaging and special effects technology of the day to give his audience a pre cinema visual experience. His original Diorama opened in Paris and he opened his second in Regent’s Park, London, in 1823. As many as 350 patrons would file into an auditorium built on a rotating platform. Most would stand and some would sit in rows on tiered stadium seating to view a very large landscape painting. This would change its appearance both subtly and dramatically. The effects were so delicately and finely executed that the audience was astounded and thought that they were looking at reality. The show lasted some 15 minutes, after which time the entire audience (on the massive turntable) would rotate to view a second painting. Later models of the Diorama theatre even held a third painting. The large images were hand-painted on linen, which were made transparent in selected areas. Behind the proscenium a series of these multi-layered, linen panels were arranged in a deep stage truncated tunnel. These layers were illuminated by sunlight re-directed via skylights, screens, shutters, and colored blinds. Depending on the direction and intensity of the manipulated light, the scene would appear to subtlety change as scenes do change in nature with the time of day and different weather conditions. | |

Panoramic Photography | |

San

Francisco panoramic image. Click the image to see an enlargement San

Francisco panoramic image. Click the image to see an enlargementThe advent of photography and its rapid development in the second half of the 19th century also saw the increasing popularity of a technique for creating a panoramic image. This panoramic technique involved the joining together of separate images of a wider panoramic view to recreate the original wide view, essentially just as in Cinerama. It became a popular early photographic technique. Here is a panoramic photograph, of extremely high resolution in its original form, of the ruins of San Francisco after an earthquake which dates from circa 1906. The panoramic image consists of five separate panel images joined together. | |

Possible Cylindrical “Panoramic” Magic Lantern Possible Cylindrical “Panoramic” Magic LanternDuring this period, the pre-cursor to the slide projector, The Magic Lantern, also became a popular form of entertainment and communication. As photographic magic lantern slides developed the techniques were developed to produce panoramic projected slides. However despite repeated prolonged research on the subject, I have never come across an example where two or three or more lanterns each projected a separate panel of a panoramic image onto the same screen. There does not seem to be any examples of panoramas being created by the separate projected panel images being aligned on the screen to recreate the original panoramic view. Panoramic slides were projected through a single projector so that the viewer could only see a part of the panorama at any given moment of the viewing of it. Whilst the vertical stacking of two or three magic lantern projectors was common in the later stages of magic lantern presentation this was for the purpose of achieving smooth dissolves from one image to the next or other effects during a presentation. However an unusual 4 lens lantern was offered on ebay a little while ago The seller suspected it was a "Kaiser" optical panorama, with a rotating internal slide mechanism and four separate (identical) projection lenses. The lantern appeared as if it would project four images at the same time to four screens. It was in fairly poor condition and it is confusing to know whether or not it was manufactured as a multi image multi screen device or an amateur adaptation of a manufactured model. At the turn of the twentieth century cinema and motion pictures had been invented and everything was in place to help the development of large panoramic multi panel large screen cinema. World Fairs, International Exhibitions and later on Theme Parks proved a major impetus and catalyst for the development of this kind of immersive large screen cinema experience. | |

Cineorama - at the 1900 Paris Exposition | |

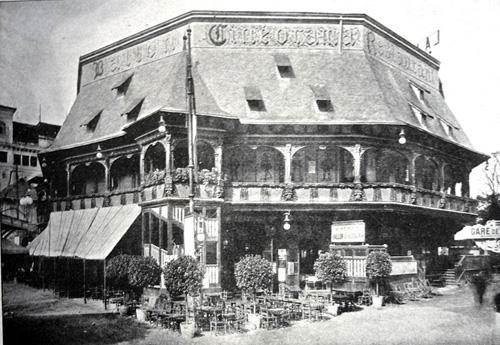

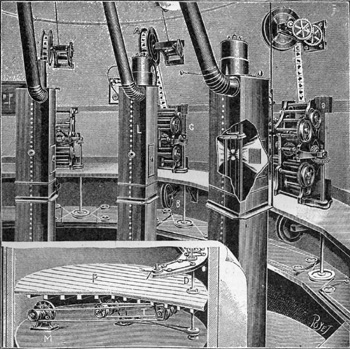

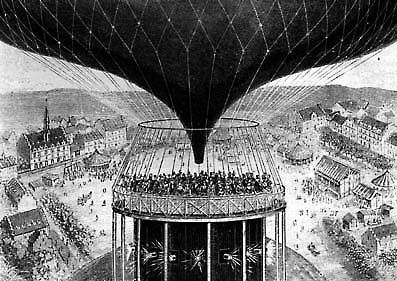

Cineorama Building (1900) Cineorama Building (1900)The 1900 World’s Fair in Paris provided an opportunity to show what cinema and experiments in large screen multi image presentation could achieve. The Cineorama process housed in a purpose built building emerged as format for the presentation of an image that literally engulfed audiences. It was almost like an early theme park ride that was a union of the earlier technology of panoramic paintings and recently invented film projectors. Devised by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson, the Cineorama experience simulated a hot air balloon ride over Paris. Visitors climbed up onto a platform that essentially reproduced the effect of being in a large hot air balloon basket with rigging and the lower part of the hot air balloon above them. Up to 200 visitors could be in the basket for the ascent and descent. Beneath them was a projection room with 10 synchronized 70 mm movie projectors, projecting onto 10 9x9 metre screens arranged in a full 360° circle around the viewing platform. At the appropriate moment the synchronised projectors showed an especially made film shot from the basket of a balloon rising over Paris and at another appropriate moment, the film was projected in reverse to simulate the return and descent of the balloon. The film was shot using a camera rig of 10 cameras with a single central drive locking them together in synchronisation. The film was made from a balloon that ascended to a height of 400 feet above the Tuileries Gardens in Paris. | |

Part

of the Cineorama Projection Room Part

of the Cineorama Projection RoomOne of the problems was that in 1900 when there were up to 200 people standing on the roof of a projection room that had ten projectors and ten arcs and not an insignificant amount of nitrate film below their feet, you had a significant safety issue. The Cineorama only operated for three days because following an operator fainting from the extreme heat in the projection room the police, fearing the possibility of a catastrophic fire closed the building. Cineorama clearly preceded Circle Vision 360°, which was introduced at Disneyland in 1955 and Circlorama, the system that ran using 11 35mm film projectors on a 360 degree screen in central London in the nineteen sixties, and the various other variations of 360 degree exhibition systems. By all accounts the people who did get to experience Cineorama during those three days in 1900 seemed to have related that it was quite an experience. In Kevin Brownlow’s book on the film “Napoleon", he indicates that Abel Gance was clearly aware of Cineorama (P.119). Other sources seem to imply that Cineorama was a part influence in Abel Gance’s conception of his three panel triptych Polyvision process. | |

Widescope 1922 /1923 - The Work of John D. Elms & George Bingham | |

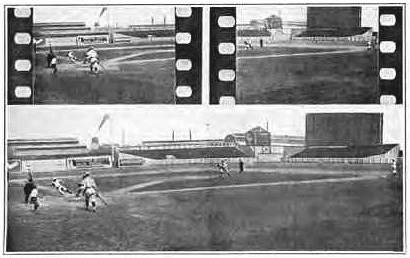

The

2-strip Widescope Process The

2-strip Widescope ProcessThe Widescope process involved a camera with two lenses centred above each other and a mechanism to ensure that they focused in perfect synchronisation. Each lens was slightly offset to each other in order to photograph either side of a wider panoramic view. This meant twice the horizontal visual angle of a single lens camera was filmed. The two strips of film photographed in synch were then projected by connecting two projectors of any standard make with a rod and universal joints and aligning them to make one wide picture on the screen. | |

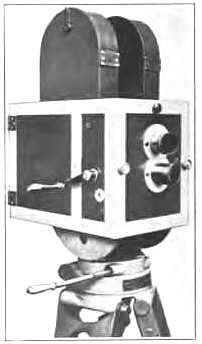

Two Lens Widescope

Camera Two Lens Widescope

CameraThe Widescope process had two things to perfect. The merging of the two images on the screen, where they joined in the middle, and also the issue of parallax error. In filming with two lenses situated one above the other the parallax error in the difference in what the two different lenses “see” and film increases as you begin to decrease the camera to subject to camera distance – i.e. the more closer the shot the bigger the difference in what the two lenses film. This increases the problem of aligning the two images side by side on the screen. Sources record that some of these problems were part overcome. Widescope / Widevision was shown commercially for a time at the Cameo Theater in New York City beginning on November 9, 1926. | |

Abel Gance - “Napoleon” 1927 | |

Almost simultaneously to the development and commercial showing of the two

panel widescreen process of Widescope, French film maker,

Abel Gance, was

overcoming the problems of making his epic masterpiece “Napoleon”. Almost simultaneously to the development and commercial showing of the two

panel widescreen process of Widescope, French film maker,

Abel Gance, was

overcoming the problems of making his epic masterpiece “Napoleon”.In particular, in Kevin Brownlow’s book on the subject, he relates how Gance was realising that for some scenes he was conceiving, the single almost square aspect ratio screen was not big enough to contain the scale of the scenes he wanted to depict and convey. His solution was to ask the Debrie camera company to construct a three camera rig with now three lenses slightly offset to each other in order to photograph the three parts of a now very much wider panoramic view than Widescope. Again the idea was to align the three panels of the triptych image on a large wide screen. The vertical mounting of three cameras had inherent parallax problems. First test filming using this camera rig took place in February 1926. This year of celebrates the première of “This Is Cinerama” sixty years ago on 30 September 1952, at The Broadway Theatre in New York. Reports on the premiere describe the shrill screams of the ladies in the audience and the utter amazement of the men when the huge screen was opened to its full size and the audience was immersed in a thrillingly realistic ride on a roller-coaster. It is easy to forget that Abel Gance had done almost exactly the very same thing twenty five years earlier. The Cinerama opening made the front page of The New York Times and its gala première was attended by amongst others, the New York governor, the chairmen of NBC and CBS, Broadway composer Richard Rogers and Louis B Mayer, The New York times wrote: People sat back in spellbound wonder as the scenic program flowed across the screen. It was really as though most of them were seeing motion pictures for the first time.... the effect of Cinerama in this its initial display is frankly and exclusively "sensational," in the literal sense of that word. Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” and the legendary three panel Polyvision triptych was premièred at the old Paris Opera house (Opera Garnier) on April 27th 1927. Admittedly there was no synchronised sound – it was a silent black and white film accompanied by an orchestra – but accounts relate to the amazement of the audience when the curtains opened and the full scale of the large wide three panel image was projected. The whole film and triptych was sensationally received by the audience and at the end of the film and the triptych sequence the audience rose to its feet and gave Abel Gance a fifteen minute standing ovation. In the audience was a young Charles de Gaulle and another Frenchman Henri Chretien. “At the end of the film and the triptych sequence the audience rose to its feet and gave Abel Gance a fifteen minute standing ovation.“ In later life Gance mounted the original three Debrie cameras he used on the triptychs in “Napoleon” horizontally, and post the unveiling of Cinerama, called his revised new three camera / projector system Magirama. It is difficult not to conclude when seeing the last twenty minutes of “Napoleon”, in the three strip version it should be seen in, that Gance got to and successfully executed the Cinerama process long before Waller did. Brownlow’s book indicates that both he and Gance certainly thought so too. | |

Henri Cretien's Hypergonar Lens

| |

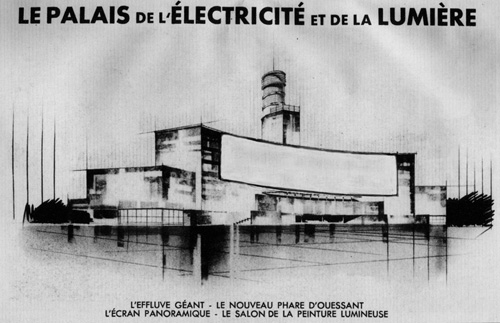

Artist’s illustration of the curved panoramic screen at the Pavilion of

Light 1937 Artist’s illustration of the curved panoramic screen at the Pavilion of

Light 1937In a letter addressed to Abel Gance dated 3 July 1953, Chretien confirmed that 'it was seeing your film “Napoleon” at the Opera that gave me the idea to apply to panoramic images an apparatus I had conceived for military purposes'. It is important to note that Chretien acknowledges that it is Gance’s triptych that inspired him to conceive of and perfect his Hypergonar anamorphic lenses. Henri Chretien reacted very quickly to the presentation of Abel Gance's film: three weeks after the premiere of "Napoleon" at the Opera, he had his cousin Georges make a confidential patent application. Chretien was probably aware of Abel Gance's innovation even before the film's premiere, as the shooting of most of its triple panoramic images in August 1926, near Toulon, had received significant newspaper coverage in France. The apparatus was far simpler than Gance’s, because only one anamorphic lens was needed to be added to a standard camera lens in order to obtain a “squeezed” wide panoramic image onto a 35mm film frame and then a lens added to the projector lens to “unsqueeze” it back into to the wider image on projection. It was the occasion of another World's Fair in Paris in 1937, that provided Chretien an opportunity to demonstrate the possibilities of his Hypergonar process on a 60 metre by 10 metre screen. He used two Hypergonar lenses to project a composite of two “unsqueezed” anamorphic images side by side (as in Widescope) on an extremely wide aspect ratio screen. Each of the two separate projected images were 30 metres by 10. The screen on the outside of the Pavilion of Light building and was curved concave like the exterior of the building wall itself. The curved wall compensated, in part, for the distortion introduced by the cylindrical projection lenses, maintaining a constant distance in the projection throw from centre to sides. A short film entitled “Panoramas au fil de l’eau” commissioned by the Paris energy company was projected on this outside screen nightly for five months. Another short film commissioned by the same company entitled “Phenomenes Electriques“ was also shown on the same screen. As we know Chretien sold his Hypergonar process to Twentieth Century-Fox in 1952 and CinemaScope and modern single lens widescreen cinematography was born. | |

Enter Fred Waller | |

Cineorama Interior (1900) Cineorama Interior (1900)Yet another World’s Fair in New York in 1939 featured Fred Waller projecting a mosaic of still pictures on a curved screen. It was at around this time that Waller was experimenting with peripheral vision as a component of the illusion of depth. His colleague Ralph Walker has explained that Waller was interested in a curved screen as a means to delimit the field of vision in viewers and convey a sense of the all-embracing environment in the experience of a film. Waller reasoned that if a giant curved screen could provide a closer replication of the human field of vision then anyone watching it would feel as if they were right in the centre of the action. The impact of the curved screen became an integral part of Waller's gunnery trainer in the early 1940s and his subsequent experiments with Cinerama. One has to concede that this is a difference to Gance’s concept, but is it really big enough to deny that Gance got there first? | |

Familiarama Cinerama | |

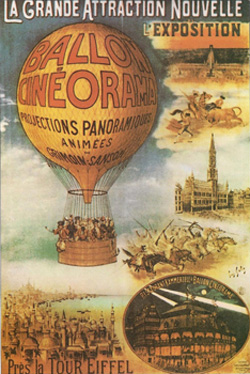

Cineorama Poster Cineorama Poster

If the painter Roger Barker, who made a fortune with his Panorama in the first half of the nineteenth century, and Louis Daguerre, who built Dioramas, could have attended the 1952 debut of Cinerama they might not have been totally surprised by what they witnessed. They may have been totally amazed at the dress of other members of the audience, the price of refreshments, the amazing multi channel sound and the photographic reproduction of the images that moved so smoothly on the screen. However, if they had been able to look around the auditorium and analyse what was happening, I am sure that they would have recognised that the concept of Cinerama, was not all together that very far removed from their earlier Panorama, Diorama and other things they had dreamed of and conceived. There is an impressive list of film formats, multi panel and others, at Wikipedia: | |

References | |

|

•

wikipedia.org • New York Times archives • Markman Ellis. Spectacles within doors: Panoramas of London in the 1790s. Romanticism 2008, Vol. 14 Issue 2. Modern Language Association International Bibliography Database. • Sophie Thomas. "Making Visible: The Diorama, the Double and the (Gothic) subject." Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Robert Miles. 2005. Praxis Series. 31 Jan. 2010. • Kenneth MacGowan (Spring 1957). "The Wide Screen of Yesterday and Tomorrow". The Quarterly of Film Radio and Television 11 (3): 217–241. doi:10.1525/fq.1957.11.3.04a00020. • Bernard Comment (1999). The Panorama. London: Reaktion Books. p. 76. ISBN 1-86189-042-7. • Laurent Mannoni. "Raoul Grimoin-Sanson". Who's Who of Victorian Cinema • "The Panoramas of the Paris Exposition". Scientific American Supplement (1287): 20631. 1 September 1900. • Kevin Brownlow. “Napoleon”. Threefold Music 2009. ISBN 978-1-84457-077-5 • Henri Chretien, Bernard Natan, and the Hypergonar. (CinemaScope) • Article from: Film History | January 1, 2003 | Meusy, Jean-Jacques | | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |