mr. cinerama |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Ralph G. Martin, True Magazine. Photographs for TRUE by Myron Ehrenberg. August 1953 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

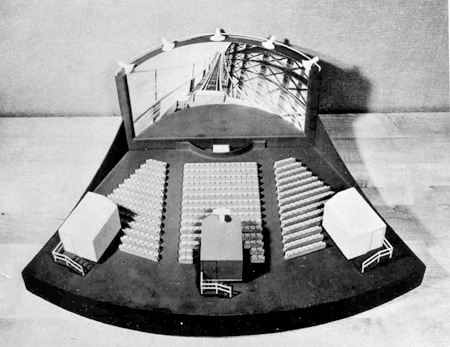

Eye filling curved picture from three projectors and ear filling sound

from multiple speakers made Cinerama seem real. Rollercoaster in this

scale model gives the audience a hair-razing ride. Eye filling curved picture from three projectors and ear filling sound

from multiple speakers made Cinerama seem real. Rollercoaster in this

scale model gives the audience a hair-razing ride.The way things are going, don't be surprised if movies become "feelies" - and Fred Waller is just the man to create them. For this nonstop inventor, Cinerama was just an afterthought The movie man from Hollywood couldn't get over it. He was watching a preview of Cinerama, a three dimensional film show you could almost reach out and feel. After some scenic panoramas, the Hollywood man excitedly nudged his neighbor. "Can you imagine something really sexy up there, like maybe Jane Russell"? he said. "Imagine catching and feeling every bounce, every curve". The mild mannered man next to him smiled, then commented, "But could you stand it"? The mild man was Fred Waller, and he knew what Cinerama could do, for it was his creation. But then so are a surprising number of things. During World War II, Waller was busy on top-secret research for the Army. He had just remarried and wanted to surprise his new wife by completely re-decorating their bedroom. Since he had no time during the day, he managed to persuade Macy's to open their doors an hour earlier, just for him. Within that hour - during which a woman might quibble over a single pair of curtains - Waller made a hundred snap decisions, expertly selecting everything from the color and weave of materials to the candlepower of dressing-table lamps. The breathless salesman finally asked him, "Pardon me, but what the hell is your business"?. It was a good question. |

More

in 70mm reading: in70mm.com's Cinerama page Internet link: |

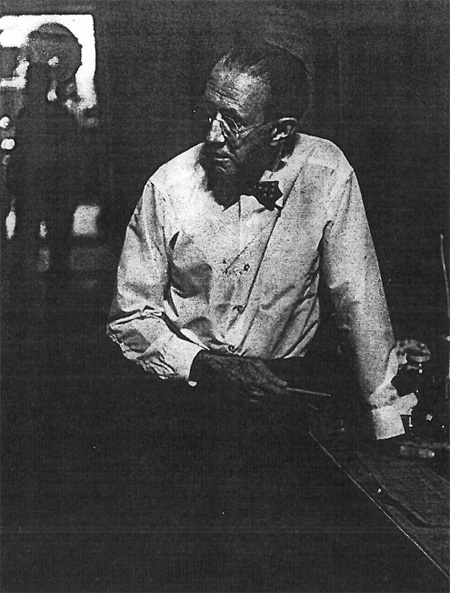

Ideas that Waller

sketches on the train go into his well staffed barn-workshop and come out as patentable inventions. Ideas that Waller

sketches on the train go into his well staffed barn-workshop and come out as patentable inventions.You get the best answer today by going home to Huntington, Long Island, with him and taking a look in his barn. In a train station crowd you can't tell anything from Waller's appearance. He's a tall, slightly stooped man who wears rimmed glasses, conservative suits and gray ties. His hair has thinned, but there is no gray in it. And his face has so few wrinkles you'd say he was twenty years younger than his actual 66. His earliest Cinerama model consisted of eleven movie cameras, carefully mounted and synchronized. The government man he showed it to wanted to know, "Where did you make this?". "In my barn", said Waller "You must have some barn". It's a big place, doesn’t look like much from the outside - old, rambling, ramshackle. But inside, it's an inventor’s dream-workshop; you find machines and tools to make everything from a miniature bolt to a complicated motor. Most of his tools are carefully catalogued and hung on a series of outhouse doors which swing open like pages in a book. More than that, it's a barn full of history and mystery. Stacked near the door are a bunch of battered boxes, still labelled "Byrd Expedition". Dangling from the ceiling are scale models of all kinds of planes and planets, souvenirs from some of his shows at the New York World’s Fair of 1939. On the wall, there is a sign that says "Waller Studios", a memento of the days when he pioneered in the film trick world and produced hundreds of movie shorts and juke-box films. Look up where a chicken coop used to be and you see a strange boat on skis. Examine an odd box on the table and you find it's a Waller camera to measure you for clothes photographically, a system now in trade use. At first the barn looks like one big confused clutter, but you soon grasp how well organized it is. One corner is the camera corner, where you see a current project - a still camera that photographs in a complete circle. Close to the camera is a darkroom, ventilated by hidden fans and louvers. As well as his fun, Waller values his friends, and he likes to make them laugh. He once spent a whole day hunting for one of those huge, curved, window display pieces of peanut brittle that weigh some 30 pounds. He put it under his coat, wearing it like a piece of armor, and went down to the boat to see his actor friend Osgood Perkins off to Europe. Waller waited for Perkins - who loved the stuff - to come up with the running gag, "Hey Papa, where's my peanut brittle?". And then Waller gravely pulled out the 30-pound morsel. |

|

|

Waller invents a different big gag for every party. Once when his guests

started whooping it up the window crashed open and in came a pink

elephant (with Fred in the front legs), and it promptly gave birth to

live rabbits. "Those parties are just for old friends", says Waller How does someone get to be an inventor-photographer anyway? Fred Waller was born into it. His grandfather invented a number of things, including a floating steam derrick which Waller says is still operating in the New York City area after 106 years. Fred's father was probably New York City's first commercial photographer, making photo catalogues for salesmen. So Fred's family wasn't too surprised when Fred got into Long Island Sound, a mile from the shore, holding a home made sail (with two pieces of wood with canvas) and let a southwest wind blow him ashore on his belly. Fred was only 8 then.  That antique Welsh cabinet is deceptive...naturally since it is Waller's handiwork That antique Welsh cabinet is deceptive...naturally since it is Waller's handiwork"But I grew up in Brooklyn's Victorian era", said Waller. "I had to wear long curls and a velvet suit and it wasn’t too easy to live that down. Then my folks sent me to Brooklyn Poly Prep and I was a damn poor student, because I was rebellious. I thought most of the stuff they taught there was just a lot of tripe". He got pneumonia when he was 14 and never went back to school. "If I had, they might have kicked me out anyway. After that my father wanted me to go to college, but I wouldn't go. I found out that I needed two modern languages and two dead ones to become a mechanical engineer and so I said "To hell with it". From then on, Fred Waller had had only one teacher - himself. Much reading, but no novels, no murder mysteries - just technical books, technical magazines. "I wanted the meat. I wanted to know why things work. The basic physics and mechanics of it, and no frills". He went to work for his father, sweeping his shop. The biggest joke in his father’s photo studio was a sign. Beware of Machinery. It was funny because there wasn't a single machine in that shop until Fred Waller invented one a few years later. It was a huge photographic machine, 10 feet high and 40 feet long, that printed, developed and dried 1800 prints an hour.. This machine helped the skinny, sensitive Brooklyn boy build up a business that soon produced 90 percent of all display photos used in movie-theatre lobbies. Display-picture production was in the millions when Fred got a call late one night telling him his plant was on fire. None of it was insured. "How soon will you be down here?" the excited caller wanted to know. "I'm not coming", said Waller quietly. "Then what are you gonna do"? "Tomorrow is a big day. I'm going to sleep" His wife stayed up all night worrying but Fred slept soundly - while everything at the plant burned down to a total loss. His struggle upward after that was slow, and then again he got slammed. The disappearance of chemicals and photographic paper during World War I crumbled his photo business. And his marriage had reached the breaking point (his first wife and two children are still a closed subject, even among his nearest friends). |

|

|

"Every time I think of Fred", says an old lawyer friend, "I think of

bang, bang, bang, struggle, struggle, struggle. In this early days

especially, he had to grub for money and fight for his ideas to get

people to believe in him. Most people with money think that

inventors are just a lot of crackpots". Waller really started working his imagination when he took over Paramount's Special Effects Department with the motto, "Anything you can put on two dimension paper, I can put on two dimension screen". It wasn't so easy. D. W. Griffith once wanted photographic close-ups of flying angels. Waller wired some actors to the ceiling but they passed out under the hot lights. As a helper Ken Adams, tells it: "Fred sent me down to a gym to pick up some of the non-fainting angels. I got five cabloads of them, really tough-looking pugs, and I remember one of them got cold feet and stopped the cab near Queensborough Bridge and said, "I ain't going through with this. I ain't no angel". You should have seen the rest of them after Fred's make-up man got through with them: long blond curls and chiffon and powder and 6-foot wings and a silver harness around each gut, all of them about 25 feet up there flying around looking unhappy as hell. That was some scene, but what a crummy picture".  Step up and the proprietor will mix you any drink, including some he invented Step up and the proprietor will mix you any drink, including some he inventedWaller set the work pace. Waller assistants often worked around the clock in shifts and slept on grass hula skirts left over from a South Seas picture. One new man checked in and didn't go home for thirty days. Waller once got only twenty two hours sleep in eight days, then worked seventy-two hours without any sleep at all, without a shave, without changing his clothes. "I've seen that man so tired he couldn’t talk. He had to make signs to me to tell me what to do", said another former Waller worker, Eugene Laroche. "And yet, when the tension among his men got really rough, usually just before sunrise, Fred would always come out with one of his limericks - he knows a million of them - and that would explode everybody into laughter. "I'll tell you something else", added Laroche. "I've worked with that man for thirty years, and never once have I seen him get mad, not even once. I tell you. Now how about that?" Technicians still ask Waller how come he thought of inventing the Optical Printer? Waller's answer was simple: "I had to. I was working too hard". Waller's Optical Printer did almost everything: could reduce a movie frame, blow up any part of it, distort it, revolve it, even create a whole movie scene by superimposing up to seven film strips onto a single film. It saved weeks of work. One thing Waller never learned about the movie business - he couldn’t be a yes man. So he and Paramount had several job intermissions. He didn't have a dime left when he married his second wife and she had only 34 dollars, so they postponed their honeymoon. And when they finally saved up enough to go some place. Fred said "Let's buy a boat instead". They bought the Islander, a tubby black-hulled sloop, a shallow draft center boarder. Fred installed a kicker - a Ford Model A conversion that he put in himself. Most of his marine inventions - and he had a fat pile of them - simply grew out of his love for Islander, his wish to keep improvising it: a solid-alcohol stove with a special flue arrangement to control the flame's height and intensity, an anemometer to bring the wind-velocity statistic inside your cabin, a simplified boarding ladder, and adjustable sail batten, a way of steering and changing ship speed from the crow's nest of the ship. |

|

|

A friend introduced him to skiing. Fred got all excited about it and

wondered aloud how much fun it would be to ski on water. Everybody

thought that it was very funny, including Waller. But the idea stuck with

him, kept stirring him, until he went to his barn and produced something

never seen before - a pair of water skis. He insisted on being his own

guinea pig, and became an expert: he let himself be towed by his teeth,

even put stilts on his skis and rode them for the newsreels. "I had so much confidence in Fred", said photographer friend Eugene Laroche, "that I went out on those skis even though I didn't know how to swim". Water skiing stayed a fad until Waller's ski patent expired. Now it's a hot American sport. Challenge is a big thing with Fred Waller; it's the basis of much of his life. "Some idea will challenge him and then time means nothing", said his friend Gordon Thompson. "Out comes that drawing board and slide rule and he'll work right through with it. Once he sets a fire under a problem, he stays with it". "If you ask me", says another friend "the trouble with Fred is that sometimes he sets too many fires, and then drives on all of them until he is almost ready to be packed in a box. And that's why he stutters, too". "It isn't a stutter", explained Lanny Ross, the singer. "It's an occasional halting hesitation in his speech. I do it myself sometimes. You are talking to somebody but you are thinking of other things way ahead of what you are saying.  A self-taught engineer, Waller passed up college as waste of good time A self-taught engineer, Waller passed up college as waste of good timeIt was always that way with the Geneva movement, a mechanical gear device. Waller was tied up in a dozen projects that had nothing to do with the Geneva gear, but he suddenly started thinking about it while he was talking to somebody about something else. The Geneva gear is a basic motion-picture machine part. Waller spent a lot of his train-riding time - he says he gets some of his best ideas on the Long Island Railroad - playing with diagrams on paper. Then one day he told his engineer assistant, Frank Richmond, "I think I know a way to turn the Geneva gear inside out". Richmond was a fat little boy who rode Waller's water skis in 1925, has worked with him ever since, knows him as well as anybody. "Now I think you really have gone crazy", said Richmond sadly. Waller shrugged his shoulders, handed him his diagrams, forgot about it. Weeks later, a tired-looking Richmond walked up to Waller and said quietly, "It works". "What works?" said Waller, already wrapped up in a number of other things. "Your inside-out Geneva gear. I made this model just to prove you were nuts. But it does work, it really does". |

|

|

Waller still has that model on his desk. Since then they've started

using it in England to index dyes on a punch press. He does a lot of things "just for fun". Back in the 20's, he saw a newspaper story about a coming lunar eclipse and decided he'd photograph it. Astronomers had spent months planning film procedures for it, and all he had was a couple of days. But that made the challenge more interesting. He remembered an old Brooklyn neighbor who knew all about astronomy and phoned him to find out the relation of the outer light to the full moon. Then he borrowed his father's lenses to make up an assembly yielding a 29-inch focal length, got some special experimental sensitized film and kept it on ice, then took his pictures at 4 in the morning. Astronomers say that Waller's eclipse pictures are among the best ever taken Waller went back to Paramount as head of their Short Subject Department and produced, directed and photographed 365 movies within eight years. He filmed many of the things that interested him personally, from birds to frozen fog to deep-sea delicacies to a Rube Goldberg invention Fred picked one of Rube's craziest cartoons - a choice insanity which Rube himself swore could never be worked and was willing to bet prohibition whisky against. It was called "How to get rid of a bore". Waller made a hula dancer's shimmy excite a tiger whose motion rubbed a flint, caused a spark, lit a candle, burned a rope which released a lever and dropped a big foot which kicked the Bore right through the window (fake glass which Waller formed from melted sugar). Waller got his whisky. Fred Waller could be found in a lot of places in those days: researching underwater photography problems in the bottom of Brooklyn's St. George Hotel swimming pool, or in cold storage 65 degrees below zero testing equipment for Byrd's first expedition to the South Pole. Waller also edited the final Byrd film, and used a sledgehammer to do it. Byrd's most dramatic story about the polar trip was the sudden splitting of the ice into a gaping crevice. But it never got photographed. And their camera had jammed when they dropped the American flag from the plane onto the Pole. So I got a big crystal-covered block of plaster of Paris", said Waller, "and I photographed it before and after cracking it with a sledgehammer. As for the flag shot, I had a flag dropped from the top of the Paramount building, photographed it on the way down and used a still photo of the Pole as a background shot. Then I put both shots in the final film and nobody ever knew the difference." At about that time, Waller's boss told him to cut his budget and staff in half and produce the same number of pictures. Waller said, "Nuts", and quit. Every time he quit Paramount, he started opening doors to other projects. He designed Florida's famous Marine Land Aquarium, originally conceived as an underwater photographic studio and never found time to visit it. Cinerama was only a vague glimmer of an idea then, an idea that if people use the sides of their eyes as well as the front, looking at a curved screen, they can almost see a new dimension. |

|

|

Waller put that idea to its first test in some of the four shows he put

on at the New York World’s Fair. For the Kodak show, he projected

synchronized color slides to 50.000 times their original area onto a

huge semicircular screen. (Kodak still shows a smaller version at

their Rochester Photography Museum). And for the Perisphere show, he

extended the same idea in a slide series to make it look like a panorama

movie of people marching over a hill into the sky. But he got his

strongest audience reaction- -some people screamed and raced for the

exits - at his Space show where his combined use of pictures, light and

sound made people feel they were flying through space. Film notches set

off flash bulbs to show different objects in space, and set all bulbs

off at once when they went through the heart of a comet. But those fair shows had an even bigger effect on Waller. They proved what he had suspected: not only about this film "third dimension", but about its emotional impact - and that it could be achieved without having to view it through red-and-green spectacle lenses or Polaroid glasses. And it raised the challenge: if he could do it with multiple projectors and still photography, why couldn't he do it with movies? He needed more money for his research so he went to work producing juke-box or peep-show films. It was only later that he found out that his boss was just a respectable front man for a hijacker. "Still, I never had any trouble with tough guys", said Waller. "They are simple fellows - you talk their language and you lay it on the line to them, and they lay it on the line to you, and it works out fine. So what if they carried guns. I remember once when I took over my brother's waterfront business when he was sick - I was only 17, keeping a fat payroll in my pocket - I carried a gun, too". Waller really impressed a borrowed secretary by directing an intricate musical comedy number while he dictated to her the highly technical details of a new idea. His second wife having died, he later married that secretary. As for that new idea, it became a Gunnery Trainer that played a highly important role in World War II. Waller needed a bigger barn to work out his gunnery trainer, so he took over the former stables of the Rockefeller family in New York. The trainer is a huge ugly thing. The gunner being trained perches on a seat high above the ground behind a photoelectric gun, the kind you find in a penny arcade. The room looks like the inside of a huge rubber ball. As it darkens, five synchronized projectors whir a continuous picture on the walls and the gunner gets the feel of being thrust through the clouds, sitting in a gun turret of a bomber flying several hundred miles an hour. He can even see the tail of the bomber just ahead of him. Suddenly he sees a spot, watches it grow quickly into an enemy plane diving straight at him, barely giving him time to sight his gun and press the trigger, his hands shaking under the recoil. The noises are now the same noises he'd hear in combat flying. Another plane dives at him from another angle, and e beep sounds through his earphones when he's dead on target, every shot registering on a master control board. Still more planes and he's spinning and firing and it's no longer a game - the sweat is real sweat, the fear is real fear.' One hour in a Waller Trainer equalled ten hours in a big bomber. And more time was saved, for in ordinary flight training the Air Corps expected one death every 6000 flying hours, a wrecked bomber every 12000 hours. Waller graduates seemed better gunners, too. The first Waller-trained Flying Fortress gunners shot down 90 percent of the attacking fighters on their first mission without a loss of a single man or plane. To create the Trainer, Waller had to know much more than the relationship of thousands of wires and gears. He had to get intimate with ballistic factors, gravity drop, windage and dispersion of different guns, intricacies of optics and sound waves and electronics, and whether a shell comes straight out of a gun barrel or whether it wobbles. All this took up only parts of Waller's brain; he gave the rest of it to Cinerama. The practical fact, though, was that the trainer and Cinerama both grew from the same basic idea. |

|

|

For Cinerama, Waller boiled down his original complicated conception

from eleven synchronized cameras to three. Then he worked out a

multiple-track sound system with Buzz Reeves (five loudspeakers spaced

behind the screen, several more around the auditorium). The curved

screen was almost six times as large as the one in the average movie

theatre, and instead of being solid it looked like a vertical Venetian

blind with 1100 narrow louvers to scatter the light. Waller set the

whole thing up in an indoor tennis court, with the three separate movie

projectors, each in its own booth loaded with film bearing one-third of

the scene, beamed at a different portion of the screen. Then he invited

big-shot movie magnates to come and inspect - and maybe invest. They came, saw, were impressed, but shrugged their shoulders. "It's very nice, Mr. Waller", one of them said, "but why should we start competing with what we've got, throw out our present features, re-equip all our movie houses?. All very nice, Mr. Waller, but can't you see how impractical it is?" Waller simply smiled, went back to work. He put in all his own money, Buzz Reeves put in more, a group headed by Lowell Thomas invested the rest. It cost them some $30.000 to re-equip a theatre on Broadway. Then they opened. The theatre lights go out, and you don't just see something - you're in it. You look at a roller coaster and your stomach rolls with it, your hands grip hard on the sides of your seat, you duck your chin when you go down, down. You're at Niagara Falls, and no matter how often you've seen it - you'll never see it all - you've never really seen the trickling nearness mixed with the huge rush of the falls and a panorama miles wide - all in the same split-second view. You see an opera and you're on the stage with the singers. You're with three-dimensional bathing beauties in Florida on water skis, so close you can feel the water spray. But Waller has much bigger dreams. He remembers the Fred Waller who quit school because he couldn't stand the dull tripe and now he sees Cinerama as something that might overhaul our whole educational system, make us visual and vital. He'd like to see Cinerama teach history, geography, science, he'd like to see dry facts jump out of text books and become emotional experiences that stick. And he'd like to see Cinerama save lives. "If the trainer could produce good gunners", said Waller, "why can't we use the emotional shock of Cinerama to give the new infantry soldier a more realistic taste of war? Why can't we use it to give civilian-defense workers some shock preparation for an atomic attack? And imagine if we could use it to test all auto drivers, to give them the full force of every traffic situation, something they can never get in an ordinary road test. It's all very nice for Cinerama to entertain people and make a lot of money, but it can do so much more than that. And I'd like to live long enough to see some of it". His friends keep pushing at him to go home and relax more. It is a relaxing place. The most typical piece of Waller in the house is an antique-looking Welsh cabinet. You look at it, and almost as quick as you can blink it splits apart into a saloon bar, complete to the brass rail, spittoon, plate of cloves, and a calendar that says, Wallers's Cafe...Wines Liquors and White Slaves. Step up on the rail, and bartender Waller will mix you any drink, including a few of his own invention. |

|

|

He papered his stairway wall with thirty-seven individual sailing charts

hand-colored and painstakingly fitted to form a huge nautical map of

Long Island "Took about 1000 man-hours", said Waller, and then he laughed. "That's almost as long as it took me to give enemas to those red-headed worms". Thousands of the worms were eating pinholes in the oak beams of his huge living room, leaving their daily piles of sawdust on the floor. Waller hunted up the strongest poison, put it in a hypodermic syringe and patiently went from hole to hole. "And then I found out that those worms wouldn't really have hurt anything and that the room heat would have killed them". He laughed louder this time. "And some people tell me how smart I am". Waller also thinks a man is through id he starts saying yes all the time, or if he stops getting interested in new idea, or if he sells himself cheap. I was at a private Cinerama showing when a highly enthusiastic millionaire announced that Cinerama was the biggest thing since talking pictures. Then he pointed to Waller and added, "But I'm not going to invest any money unless I can buy you". Waller gave out his slow smile and said "Thanks, but I've never been for sale" Another friend summed up with a warmer postscript on Waller: "That guy's a happy man. He thinks his work is fun. What more do you want?". |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|