Labyrinthe |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: The National Film Board of Canada. Reprinted from vintage flyer. Text re-typed by Anders M Olsson, Sweden. | Date: 05.03.2023 |

Labyrinthe -

a project commissioned by the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World

Exhibition as one of its Theme Pavilions, was conceived and executed by The

National Film Board of Canada. Labyrinthe -

a project commissioned by the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World

Exhibition as one of its Theme Pavilions, was conceived and executed by The

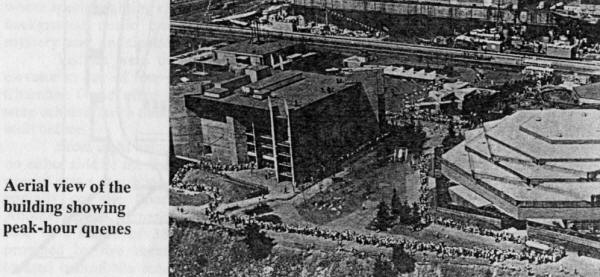

National Film Board of Canada.Back in 1964, when the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exhibition began to round up participation in what was to become EXPO 67, the ground rules they set were straightforward - "think big and use your imagination." Participants, private and governmental, took this advice to heart. Some 50 million visitors attested to the fact that EXPO 67 was, without doubt, the most popular, most imaginative and most highly-acclaimed world exhibition ever. At a very early stage, Canada's National Film Board presented a concept designed to fulfill the C.C.W.E.'s specifications. In fact, so big and so imaginative was the NFB "Labyrinthe" proposal that potential sponsors blanched at the project. Fortunately, EXPO itself had faith in the Board's ability to produce and their faith was well-rewarded. By the time EXPO closed its gates on October 29, 1967, 1,324,560 people had visited the pavilion, many of them having waited in lines for up to seven hours for the privilege. • Go to "Labyrinthe" gallery "Labyrinthe" was commissioned as a Theme Pavilion, one of several conceived to complement EXPO's overall dedication to "Man and his World." While other theme pavilions represented man's conquest of his environment and his development as a provider, producer, healer and community-oriented being, "Labyrinthe" dealt with man's conquest of himself. The approach used was a contemporary re-telling of the Greek myth in which the hero Theseus entered a Cretean labyrinth to slay the Minotaur, a monster half man and half bull whose dietary preferences leaned towards Athenian citizens. Director Roman Kroitor explained the symbolism involved as follows: "The architectural structure is the world and the path followed by the audience while wending its way through the building is the thread of a person's life. The theatres are life's experiences and the 'beast' is the inevitably incomplete realization of one's nature which we hoped would be conquered or dispelled as one moved through the various phases of 'Labyrinthe." The presentation was more than an artistic allegory; it was also a proving ground for various sophisticated cinema techniques. Although it is difficult to determine whether the concept and symbolism were fully understood by the audiences, there was virtually unanimous agreement amongst the international film community that the techniques employed represent the coming thing in the field of visual communication. The presentation was the culmination of years of work on the part of filmmakers, architects, engineers and technicians. "Labyrinthe" is a vast topic - far too complex to be covered in detail in a publication of this size. However, this technical bulletin is designed to provide a general description of the project and the techniques involved. More detailed information on certain phases is available in the material listed in the bibliography or from the Technical Operations Branch of the National Film Board. |

More in 70mm reading: Gallery "Labyrinthe" in70mm.com's IMAX Page The Birth of IMAX See the film: "In the Labyrinth" |

The Initial Mock-up Stages |

|

Traditionally, films are made for viewing in conventional movie theatres.

While techniques have changed over the years, these changes have been

evolutionary rather than revolutionary so the most modern motion picture

theatres being built today still strongly reflect the influences of their

generic predecessors - opera houses. Basically, the audience sits in rows in

front of a vertical screen and while attempts have been made to create a

greater degree of audience involvement through the use of wide-screen

projection and stereophonic sound, the effect is two dimensional. Traditionally, films are made for viewing in conventional movie theatres.

While techniques have changed over the years, these changes have been

evolutionary rather than revolutionary so the most modern motion picture

theatres being built today still strongly reflect the influences of their

generic predecessors - opera houses. Basically, the audience sits in rows in

front of a vertical screen and while attempts have been made to create a

greater degree of audience involvement through the use of wide-screen

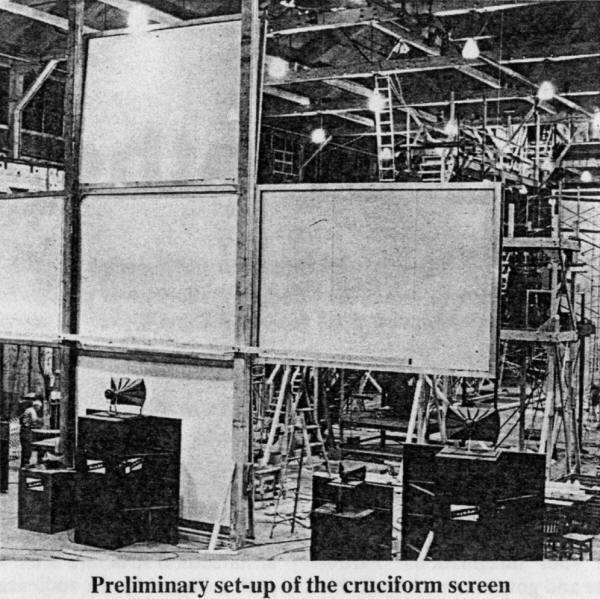

projection and stereophonic sound, the effect is two dimensional."Labyrinthe" was a departure from this traditional train of thought. The producers decided at the outset that a multiscreen presentation would best convey the concept of "Labyrinthe." Since the building itself didn't exist at the time, architectural considerations did not present restrictions. Once the revolutionary screening concepts were decided upon, architects were commissioned to design a building to accommodate the equipment. Before a single frame of film was shot or any equipment chosen, the "Labyrinthe" team experimented with various projection and sound systems until they were satisfied that the techniques chosen would convey the concept with maximum impact. This particular phase of the operation - carried out in a rented aircraft hangar in Ville St-Laurent, Quebec - involved close collaboration between the production teams, the Technical Operations Branch of the NFB, consulting engineers and architects. The multi-screen presentations finally chosen were such that no conventional theatre could be economically adapted to house the equipment for testing and the preliminary editing of rushes. Because of the nature of the material being assembled, it was desirable to work under conditions as close to those to be found in the actual building as possible. Scale models of several chambers and anterooms were built in the hangar. Wherever possible, equipment was tested in these mock-ups before being moved into the actual chambers. |

|

The Building |

|

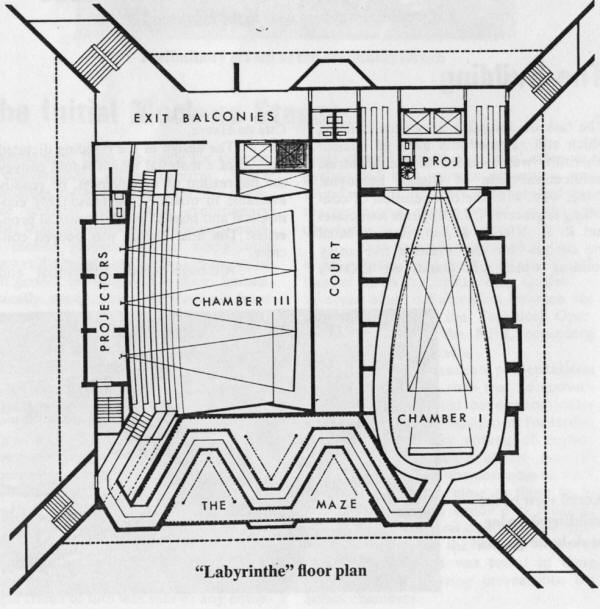

The task of designing a modern building which still retained the aura of

ancient labyrinths was awarded to the Montreal architectural firm of Bland,

Lemoyne, Shine, who, with the co-operation of consulting engineers N.J.

Pappas & Associates and R.R. Nicolet & Associates, created the designs for

the massive five-storey building which still stands on EXPO's Cité du Havre. The task of designing a modern building which still retained the aura of

ancient labyrinths was awarded to the Montreal architectural firm of Bland,

Lemoyne, Shine, who, with the co-operation of consulting engineers N.J.

Pappas & Associates and R.R. Nicolet & Associates, created the designs for

the massive five-storey building which still stands on EXPO's Cité du Havre.The design of the building dictated the use of a material which would convey the impression of massiveness, be readily available in quantity, be reasonably economical and possess good acoustical properties. The final choice was poured concrete. Although solid, substantial and equipped with heating and air conditioning facilities, the building was designed as a "semi-permanent" structure. Since much of the equipment and display material was installed during the winter of 1966, heating was incorporated even though this was not an essential feature in EXPO buildings. However, the architects feel that the heating and air-conditioning systems would not be adequate for large audiences on a year-round basis. The word "labyrinth" is synonymous with confusion; in the original Cretean structure, the hero had to unwind a ball of twine in order to find his way out again. While the illusion of mystery and uncertainty was an integral part of the EXPO re-creation, the architects had to carefully design the various transition areas to create an illusion of confusion while keeping audience flow as straightforward as possible. Passages were designed to handle vast numbers of people in a manner similar to that used in a "sausage machine". Though various groups of visitors followed each other through the building very closely, careful placement of baffles and partitions created a feeling of intimacy. Audience movement through the various chambers, anterooms and transition areas was carefully controlled by a master "programmer." An analysis of the separate operations required in the various areas showed that each presentation required less than 12 specific operations. The programmer performed the following functions: dim house lights, start projectors, start film sound, fade transition music, etc. It also automatically controlled the audience flow. To avoid congestion, the various chambers and transition areas were tied together in logical time sequence and the programmer could "hold" an audience in one area if the subsequent one was unable to accommodate it immediately. Initially, the control system was operated manually in part and handled 26 or 27 complete shows per day. Once operating automatically, it handled 30 shows per day without fail. Because of the number of people being accommodated daily, "Labyrinthe" strictly adhered to the show business law that the show had to go on regardless. Minor problems did not result in cancellations. During the six months that the pavilion was in operation, less than three hours of show time were lost. |

|

Chamber I Arrival, Childhood, Confident Youth |

|

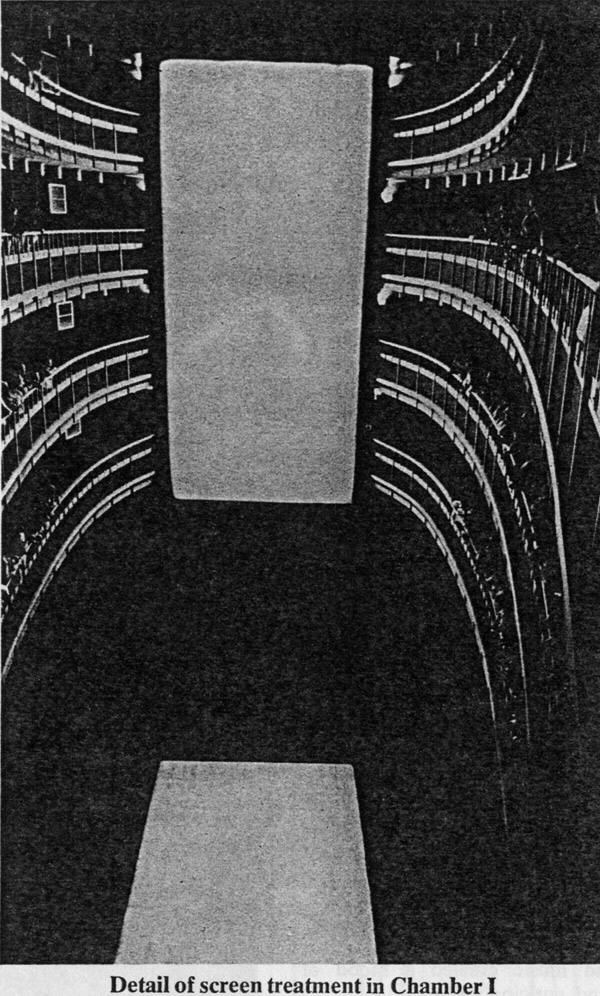

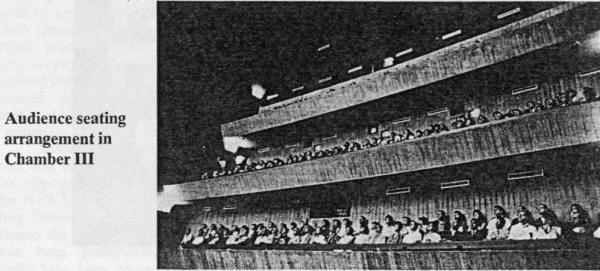

The building contained three main chambers, each relating to one aspect of

"Man the Hero." The visitor entered in a queue which wound its way through a

lobby decorated with the designs of ancient labyrinths and a sculptured

impression of the Minotaur. He then entered a high, cathedral-like court,

"The Great Hall" where special lighting effects and haunting background

music created a mood of mystery and anticipation. The building contained three main chambers, each relating to one aspect of

"Man the Hero." The visitor entered in a queue which wound its way through a

lobby decorated with the designs of ancient labyrinths and a sculptured

impression of the Minotaur. He then entered a high, cathedral-like court,

"The Great Hall" where special lighting effects and haunting background

music created a mood of mystery and anticipation.Visitors were then distributed by elevator to one of four levels surrounding Chamber I and after a brief wait, they were ushered into a theatre unlike any ever built before. From eight balconies on four levels on either side of the theatre, the audience peered down at a huge screen lying horizontally on the floor of the theatre. Another screen, perpendicular to the floor, rose to a height of 38 feet. Sound was provided by five theatre sound systems located behind the screens and surround sound came from 288 speakers positioned throughout the balcony levels. The 20-minute film presentation recalled the story of man's entry into the world, his childhood and his confident youth by careful interplay between the horizontal and vertical screens. In some scenes, the images on the screen complemented each other; in others, they contrasted. This technique, of course, presented a number of technical problems. Since one projector had to operate face down to project on the horizontal screen and the other on its side to fill the long, narrow vertical screen, considerable care had to be taken in choosing suitable equipment. After carefully considering various 70mm machines, NFB engineers chose two Century JJ-3's fitted with Hughes 5KW Xenon lamp housings and Panavision-Steinheil 95mm lenses. These projectors feature positive lubrication systems capable of operating in these unusual positions and the 5KW Xenon lamps were found to offer sufficient light output as well as more simplified operation and greater operating economy than comparable high-intensity carbon arcs. Because of the extreme viewing angles encountered in some sections of the theatres, plain matte white screens were used. The screen mounting presented an interesting challenge. A special mounting system was devised incorporating features for rapid removal and replacement of the screen material. This was necessary since there was a good possibility that the screens - particularly the horizontal one - would require frequent cleaning and perhaps replacement. One thing that was not anticipated was that the horizontal screen would become a depository for lost articles. During the six months, a variety of items were removed ranging from false teeth to ladies' handbags. The Maze Upon leaving Chamber I, the visitor was assumed to be somewhat confused as to his role in life. In this frame of mind, he entered the carefully-contrived "confusion" of "The Maze", an area filled with large mirror prisms illuminated with thousands of tiny, colored lights which flashed and twinkled creating an infinite artificial galaxy. Though the lighting effects in "The Maze" seemed random, they were actually carefully controlled through programming equipment specially designed by the NFB. The intensity of the lights was controlled through 36 narrow band filters and transistorized DC control amplifiers fed by audio information on the control track - actually the sixth audio track on the same magnetic film carrying the five program channels heard in "The Maze." The control system was so designed that it could operate either from the envelope of an audio signal or from an artificiallycreated special tone control track. In the actual presentation, a combination of both control techniques was utilized. "The Maze" was designed to symbolize the seemingly endless passages of ancient labyrinths and the combination of lighting effects and specially-composed music prepared the visitor for his confrontation with the symbolic "monster" in Chamber III. |

|

Chamber III

|

|

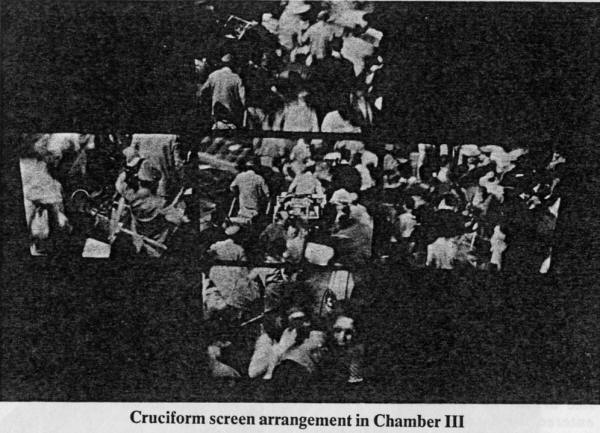

The third and final chamber offered the climax of the experience. The

visitor came face-to-face with the monster of his halfrealized self but on

the screen, this inner monster is represented by a crocodile hunted and

killed by Ethiopian tribesmen. The third and final chamber offered the climax of the experience. The

visitor came face-to-face with the monster of his halfrealized self but on

the screen, this inner monster is represented by a crocodile hunted and

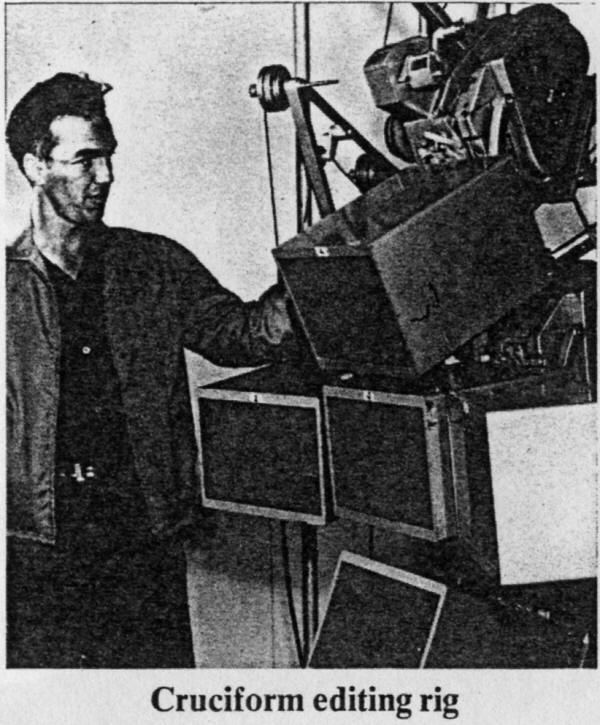

killed by Ethiopian tribesmen.Chamber III featured a multiscreen presentation, a technique very much in evidence at EXPO 67 and one which presents a variety of technical and artistic problems. The five-screen cruciform arrangement adopted by the NFB required meticulous synchronization so all cameras, projectors and editing equipment could handle five separate films with a minimum of image imbalance. Initially, a 70mm single composite print was considered. However, the idea was rejected for the following reasons: The NFB has excellent facilities for handling 35mm color material but none for 70mm; the cost of 70mm prints would have been prohibitive; image quality would have been compromised; and the theatre design would have necessitated lenses with very short focal lengths but very large diameters. The camera system finally adopted consisted of five 35mm Arriflex's mounted in a cruciform arrangement on a specially designed yoke. Since the five cameras were to operate simultaneously, interlock and registration requirements were stringent. Footage for the Chamber III presentation was shot on location throughout the world so portability was an important feature. Synchronization between the cameras was achieved through an NFBdesigned DC interlock with "Syncontrol," an electrical system offering accurate synchronization with far less bulk than mechanical devices. The interlock system also featured power requirements which could be met in the field with a reasonable number of portable batteries or, for aerial work, through standard aircraft power supplies. When the camera yoke was in use, the center camera was used as a reference point. Although it would have been preferable to have a single viewfinding lens cover the entire field of the five camera lenses, this was impractical. Because of the wide field covered by the rig, however, this was not considered to be a serious limitation. Tests and previous experience showed that the closer together the lenses could be positioned, the more compatible would be the group perspective. With the Arriflex cameras, however, the film magazines determined the minimum distance the cameras could be vertically stacked. To keep this distance as small as possible, it was necessary to use 200-foot magazines despite the inconvenience of the small film loads and also equip four of the magazines with special extensions. This permitted a 9½-inch separation between the lenses. The five-camera yoke could be operated as a unit or the three horizontal cameras could be removed and mounted on a separate yoke for shooting footage destined for the three horizontal screens in the cruciform arrangement. In addition, the baseplate of each camera was tapped to permit individual mounting on standard tripods for synchronous shooting of the same subject from different angles. The interlock system was also designed to permit separating the cameras for this shooting technique. From an operational standpoint, the five-camera arrangement worked remarkably well under harsh field conditions although extreme care had to be taken in aligning the cameras. Some problems were experienced in operating the interlock system in low temperatures but a screwdriver adjustment was incorporated so compensation could be made for any given temperature. In the cruciform presentation, the five screens alternately showed panoramic, integrated views on all screens and contrasting or complementing scenes on each of the screens. Editing the films required an editing rig arranged in a cruciform also. NFB technicians met this requirement by interlocking five 35mm D-20 Moviola heads and three Model SL-20-H Sound Readers and connecting them to a master control panel. This allowed any or all of the picture or sound heads to operate in forward or reverse, at variable speeds or at synchronous sound speed. In projecting the final print, uniform light distribution and freedom from picture movement in the various screens were essential. Manufacturers supplying suitable equipment were contacted and asked how their equipment would function under these critical conditions. Most reported favorably but it was obvious that in many cases, they had never before been asked to provide such all-inclusive information. Century WMDA 35mm projectors with Hughes 2.5KW Xenon light sources and Kollmorgan 2-inch and 2¼-inch f1.9 lenses and also featuring Cine-Focus and water-cooled apertures were chosen. The cooling features permitted still-framing for periods up to 10 seconds at full light output. Despite the complexity of the system adopted and the critical adjustments required to maintain quality, no serious problems were encountered. |

|

Sound Systems |

|

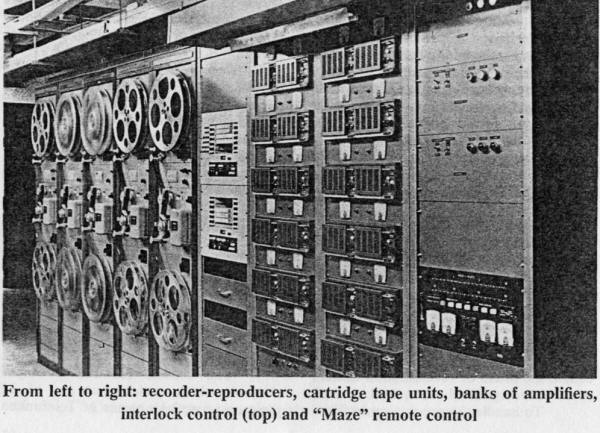

The effectiveness of the various "Labyrinthe" presentations depended on

creating a proper "mood." This involved developing special sound effects,

music and sound reproduction equipment. Much of the music used was composed

by NFB Staff Composer Eldon Rathburn; the equipment was designed by the NFB

Sound Division and consulting engineers. These engineers and technicians

faced a number of challenges. They were asked to provide high quality

equipment without sacrificing portability; special pre-mixing and mixing

consoles were required; the programming devices for crowd control also fell

into their jurisdiction. The effectiveness of the various "Labyrinthe" presentations depended on

creating a proper "mood." This involved developing special sound effects,

music and sound reproduction equipment. Much of the music used was composed

by NFB Staff Composer Eldon Rathburn; the equipment was designed by the NFB

Sound Division and consulting engineers. These engineers and technicians

faced a number of challenges. They were asked to provide high quality

equipment without sacrificing portability; special pre-mixing and mixing

consoles were required; the programming devices for crowd control also fell

into their jurisdiction.Multi-channel sound requirements were standardized on six-track 35mm magnetic film units for the three main chambers and on tape cartridge equipment for the Entrance, Waiting Room, Transition and Exit areas. The units feeding Chambers I and III were interlocked to projectors in those locations; the Chamber II unit also provided audio control information to operate the Maze lights. Original material for all sound presentations came from monophonic, two-track, three-track and four-track stereo masters and all had to be recorded for reproduction on standard six-channel playback equipment. For location recording, where portability and high-quality were prime considerations, NFB technicians found that conventional multi-track equipment was too bulky for easy transport and that it generally required external power supplies for driving the capstan and torque motors. Also, commercially-available professional equipment generally was not suited to one-man operation. The solution to this problem consisted of modifying a monophonic Nagra-Kudelski ¼-inch recorder to two-track stereo operation. Basically, the modification consisted of mating two Nagra units, utilizing only one transport mechanism, and using the two electronic packages for each of the program channels. The regular record and playback heads were replaced by two-track stereo heads produced to Nagra specifications and mounted with special headmounts onto the Nagra tapedeck. Although the original playback speakers could not be mounted into the adapted recorders because of space limitations, the speakers were enclosed in separate wooden boxes which could be plugged into the playback circuits for field playback using the recorder's internal battery power supply. The adaptation of a Telefunken FM Pilot system utilizing a 10KHz carrier frequency permitted stereo synchronous recording without the risk of the 60Hz control-track frequency straying into either of the program channels. |

|

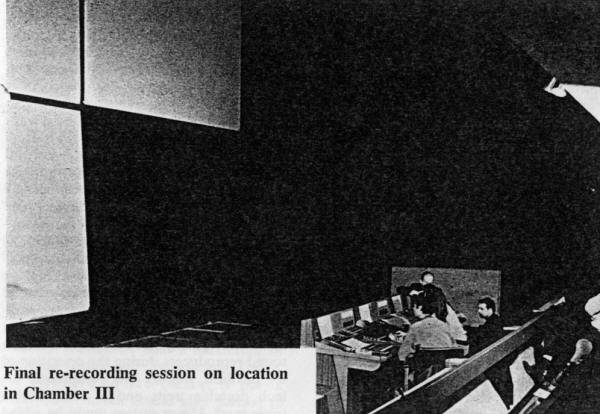

Music recordings were made with a portable 3M four-track one-inch machine

equipped with over-dubb facilities. This unit was used in conjunction with a

custom-made portable mixing console later used in recording sessions with

the Montreal and Toronto symphony orchestras. Music recordings were made with a portable 3M four-track one-inch machine

equipped with over-dubb facilities. This unit was used in conjunction with a

custom-made portable mixing console later used in recording sessions with

the Montreal and Toronto symphony orchestras.The portable console allowed random selection of input channels at either line or microphone levels as well as a choice of masters and outputs. It contained two independent sections each featuring six inputs and three outputs. When both sections were used together, input and output capacity was doubled. Each channel was equipped with "insert" jacks so equalizers, filters or reverberation devices could be incorporated as required. To handle the pre-mixing required before final re-recording, a 19-position mixing console at the NFB Sound Division was altered to six-track capability and four existing Westrex 35mm filmtransports were modified with plug-in head assemblies and printed circuit electronics to handle three- and six-track recording or reproduction. Because of the unusual screen configurations and acoustical conditions at the pavilion, it was decided that the final rerecording could best be accomplished in the completed chambers of "Labyrinthe" before EXPO opened. While this required the construction of an elaborate mixing console, it gave producers, musicians and sound mixers the opportunity of rerecording under actual auditorium conditions. This re-recording console was produced by McCurdy Radio Industries, Toronto, who also delivered the music recording console. Specifications and acceptance tests were made by the NFB Sound Division and the consulting system engineer. The console featured 21 input channels which could select any of 32 program sources by means of Telefunken crossbar switches activated by thumbwheel selectors. This was necessary to facilitate the complicated selection of monophonic, two-, three-, four- and sixtrack program sources and their distribution to the six-channel release system. For each input channel, a sensitivity adjustment, straight-line fader, variable equalizer and push-button output selector were provided. Two custom-made panpots were incorporated for the distribution of monophonic sound to the six stereo outputs. Three EMT reverberation units were available. Seven stereo output channels, each with variable active high-pass and low-pass filters, and seven 10-watt monitor amplifiers permitted control of the multi-track outputs. The seventh channel was used as a spare and for pre-set. For monophonic and multi-track storage applications, three combined master outputs were also included. The console was equipped with slating, signal and intercommunication facilities; remote controls of the reverberation units and an electronic footage counter were incorporated for use during the re-recording sessions in the pavilion itself. It was decided to standardize on double system interlock sound operation using 35mm full-coat magnetic film with one reproducer for each chamber and two alternates. Five filmtransports were purchased from Westrex, Hollywood, and equipped with transistorized electronics designed by the Sound Division in the form of plug-in circuitboards. Three of the filmtransports were used only as reproducers while the remaining two were also equipped with record electronics. All transports had custom-made three- and six-track plug-in head assemblies manufactured by Wolfgang Bogen, Berlin. These transports provided reproduction and recording facilities for the re-recording operation and then were used for transferring material from the completed masters to the presentation sound reels. Finally, they served as double system sound reproducers during the operation of the pavilion. Besides this equipment, ¼-inch portable units and a transportable triple-track 35mm system could be added during the re-recording sessions. Altec A-4 speaker systems driven by McCurdy 30-watt plug-in amplifiers were used for sound reproduction in the three main chambers. In Chambers I and III, five tracks provided behind-screen sound while the sixth provided the surround sound. In the Maze, five tracks carried the "moving" sound while the sixth controlled the operation of the prism lights. In addition, over 1,200 8-inch speakers were wired throughout the building to provide surround sound in the Maze and auxiliary locations. Sound in the transition and auxiliary areas was provided with a cartridge tape system so that the presentations could be made in continuous cycles. Two KRS cartridge systems, each with six ¼-inch tape cartridges were installed to handle requirements for non-synchronous monophonic and two-track stereo sound. |

|

Multi-Screen What is its Future? |

|

Screen formats present film-makers with a formidable challenge as they

attempt to create presentations with a maximum of audience impact and

involvement. Today, the standard square format is passé. Ideally, the screen

should alter format to suit various image requirements. The noted Russian

cinematographer Eisenstein described this ideal format as a "dynamic

square." Screen formats present film-makers with a formidable challenge as they

attempt to create presentations with a maximum of audience impact and

involvement. Today, the standard square format is passé. Ideally, the screen

should alter format to suit various image requirements. The noted Russian

cinematographer Eisenstein described this ideal format as a "dynamic

square."The multi-screen techniques employed in "Labyrinthe" were an attempt to provide a more flexible format until future technology reaches the stage where it can provide true flexibility in size, fidelity, ease of "programming," and composition. Present research into holographs indicates that the ultimate image used will probably be electronic. But what does multi-screen offer besides its obvious novelty and surprise? Writing in the 1967 edition of La Cinémathèque canadienne, "Labyrinthe" Designer and Co-producer Colin Low suggested that it offers a greater degree of composition flexibility than conventional screen techniques. It also allows the showing of the same subject at different time intervals simultaneously; it can show the same event from different positions or viewpoints simultaneously. In short, it offers simultaneity. Poetry often attempts to capitalize on this by assailing its readers with an amalgam of thoughts, feelings, word pictures and metaphor in rapid succession. In fact, some poets even abandon conventional literary form in an attempt to further compress various impressions and thus create a greater measure of simultaneity. "Labyrinthe" director Roman Kroitor described the multi-screen concept as being to the single screen what poetry is to prose. The production of a multi-screen presentation presents several unusual problems. There are no solid rules that can be laid down. While two divergent story lines can be effectively tied together by a simple common denominator (the same predominant color in all images, for example) it is also very easy to overstimulate the viewer and cause a type of optical indigestion. The judicious use of multi-channel sound is also important in multi-screen work since sound has the effect of preventing confusion between competing images. But again, care has to be taken that the result retains the nuances of the individual sound tracks. Will multi-screen concepts find their way into documentary or educational films or are they only suited to large EXPO-type presentations with budgets large enough to permit further experimentation into the medium? While it's still too early to answer this question definitively, it is very possible that some of these techniques will become commonplace in the future. Continuous advancements are being made in the fields of electronics, optics and film materials and as these developments are perfected, they will become more economically feasible. |

|

Production Credits |

|

FILM EXECUTION FILM EXECUTIONLOCATION RESEARCH: Hugh O'Connor DIRECTION: Roman Kroitor, Colin Low, Hugh O'Connor CAMERAMEN: Michel Thomas-d'Hoste, Walter Lassally, Gilles Gascon, Robert Humble, Georges Dufaux, V.V. Dombrovsky (USSR), Alex O. Krasnov (USSR) CHIEF CAMERA ASSISTANT: Douglas Bradley CAMERA ASSISTANTS: Peter Hartmann, Gilles Blais, David Devolpi, Ken Poste LOCATION MIXER: Edward T. Haley LOCATION CAMERA TECHNICIAN: John Pley FILM UNIT MANAGER: David B. Hughes LOCATION MANAGER: Marcel Malacket PICTURE EDITING SUPERVISING EDITOR: Thomas C. Daly EDITOR (CHAMBER I): Eric Boyd-Perkins ASSISTANT: Patricia Corner EDITOR (CHAMBER III): Thomas C. Daly ASSISTANT: Yves Dion SOUND EDITING CHAMBER I: Jean-Pierre Joutel CHAMBERS II & III: Thomas C. Daly MUSIC: Eldon Rathburn ORCHESTRAL CONDUCTOR: Louis Applebaum COMMENTARY: Donald C. Brittain; Claude Jutra STUDIO MIXER: Edward T. Haley SECOND MIXER: Michel Descombes PRINT COLOR BALANCING: Stuart Ferguson PRODUCTION: Roman Kroitor |

|

• Go to "Labyrinthe" for the 1967 World Exhibition |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |