Adding the Sound to Cinerama |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Hazard E. Reeves, 1953 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

Hazard E. Reeves Hazard E. ReevesTRAINED as an engineer at Georgia Tech, Hazard E. Reeves has devoted his whole career to finding belter ways to record and reproduce sound. In 1933 he founded Reeves Sound Studios, of which he has been president ever since. He also has been associated with other companies in the sound field, not to mention Cinerama, which he endowed with the most wonderful sound system put into theatrical use up to now. He has been a leading pioneer in magnetic recording. THE IDEA of stereophonic sound is not new. As far back as April, 1940 the Bell Laboratories had demonstrated the startling realism possible with a multi-channeled sound-on-film system. Walt Disney's "Fantasia" later the same year introduced directional sound for the first time to the ordinary movie-goer - at least to ordinary movie-goers seeing it in the few first run houses wired to handle the new technique. It used a three-channel recording setup, and I am sure that many who remember "Fantasia" have noted some similarities with our own Cinerama sound. In 1940, however, stereophonic sound was premature. It died aborning, and for a very significant reason. "Fantasia" linked a wide angled sound system to the ordinary, narrow screen. Technically, with its limited equipment, it worked very well, but practically, even aesthetically, it was wrong. It was wrong because it needed a wider picture to complete the illusion. As it was, sound seemed to emanate from Beyond the edges of the frame, falling off the screen in a way that proved more distracting than stimulating. |

More

in 70mm reading: The Entire Development of the Cinerama Process mr. cinerama The Birth of an Idea Cinerama Goes to War This Cinerama Show Finding Customers for a Product in70mm.com's Cinerama page Internet link: |

|

In 1940 Fred Waller, the inventor of Cinerama, invited me to a demonstration

of his new process in the Rockefeller carriage house on West 55th Street in

New York. Like everyone else who saw it at that time, I was tremendously

impressed with it, despite its crudities, despite its all-too-apparent

limitations in that early phase. Unlike so many of the others, however, I

wanted to do something about it, but Waller had to shelve Cinerama—Vitarama,

as it was called then—because of the war. Fred had already begun work on his

Gunnery Trainer. Even so, I said to him, "Fred, when you get around to

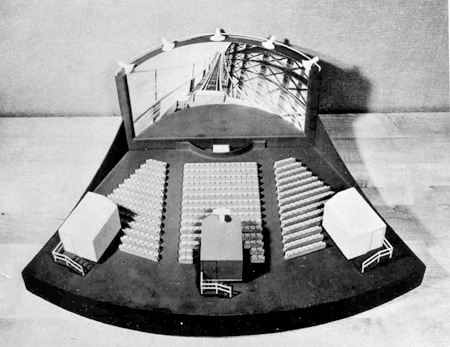

putting sound on your picture, let me know." In 1943 I started to investigate magnetic film as a means of achieving high fidelity in sound recording. The motion picture industry started off using the photographic process in sound recording which has had definite limitations. Of course, this process took the place of the Vitaphone process which used phonograph records in its sound reproduction. The limitations in quality in photographic recording can definitely be defined. The frequency response adopted by the Society of Motion Picture Engineers was a range from approximately 125 to 7,000 cycles. These standards were set up due to the limitations of the photographic printing process and also the amplifier and loud speaker limitations. These standards as originally established have continued until this day. However, it is hoped that the advent of Cinerama and the use of magnetic recording will drastically change them. FM, long-playing records and especially TV, have helped to increase the public's interest in high quality sound reproduction. The current enthusiasm for hi-fi sound in the home is symptomatic of a new renaissance in sound. I sincerely feel a new era is just beginning. Magnetic film for sound recording has proven a great step forward in raising the level of sound quality for motion pictures. From the very beginning both its greater flexibility and fidelity recommended it to the documentary people in the east. In 1948 Joseph Lerner made "C-Man" the first full-length feature using magnetic sound. The recording was done at Reeves Sound Studios in New York City. Now magnetic film for recording is being used almost entirely throughout the film industry. But this development, which should have come from within the industry itself actually was developed independently and without industry aid.  THEATRE model of a typical Cinerama installation. Projector in each of the

three booths throws a portion of the picture onto the large, curved screen.

Above the screen the five speaker horns symbolize the stereophonic sound

installation. In actual practice the loudspeakers are located behind the

screen and also on the side and rear walls of the theatre. THEATRE model of a typical Cinerama installation. Projector in each of the

three booths throws a portion of the picture onto the large, curved screen.

Above the screen the five speaker horns symbolize the stereophonic sound

installation. In actual practice the loudspeakers are located behind the

screen and also on the side and rear walls of the theatre.The same is true for Cinerama. Just after the war, Fred Waller called on me. He was ready to go ahead, working out the theatrical possibilities of his Vitarama, trimming down the Gunnery Trainer into a medium for the theatre. I joined with him, Laurance Rockefeller, Time, Inc., and several others to form the Cinerama Corporation. Fred moved into that now-famous tennis court in Oyster Bay to develop his camera and projection mechanisms. At the same time, my group began to build Cinerama's sound system. To me it was a real challenge. This would be the first multiple magnetic sound recording equipment ever devised. Since we could establish our own sound standards, we decided to go all out for high fidelity. We concluded that five loudspeakers behind the screen was the very minimum for a good stereophonic effect. (Ideally, there should be an infinite number of speakers behind the screen). In addition, we wanted speakers in the rear and to the sides of the house to create offstage effects when desired. An additional control track was also available for special use. In producing a Cinerama film, five microphones are placed about the scene to cover all the action within the range of the camera. Other mikes may be placed off to the sides, to the rear - anywhere - to record offstage effects. By spring of 1949 our equipment was complete and we had shot a number of short films to use as demonstrations. Then began the really heart-breaking part of the business. We invited everyone we could think of out to Oyster Bay - leaders of industry, leaders in the theatre, movie executives, writers, technicians. Everyone was impressed. But there was a terrifying inertia about their enthusiasm, too many "buts." It was fine, but there were too many technical problems. It was great, but it was too expensive. It was marvelous, but what would become of all the fine films in vaults out in Hollywood if this thing should ever take over? Actually, less money was spent between 1947 and 1949 in the creation of Cinerama and its first test films than is generally spent on the average Grade B movie. But it looked big, and people were afraid. Then in July of 1950, Time, Inc. backed out, followed by Mr. Rockefeller. They generously afforded me the opportunity of acquiring the assets of Cinerama Corp. I felt it would be wrong to let this thing die without giving the public a chance to decide its merits. |

|

|

The next few months were spent in an effort to interest a potential producer

in making a first feature on Cinerama. The trips out to Oyster Bay were

resumed. We invited producers, both film and theatrical. We even took out

theatre executives. This time, however, I was resolved that the process had to sell itself. Either our future Cinerama producer was going to be vitally interested in it, or we weren't going to be interested in him. I decided to take literally that old kiss-off line, "Don't call us, we'll call you." And we did get some nibbles. Hal Wallis, the movie producer, began negotiations. It was even announced in the trade papers that he was going to produce the first Cinerama feature. But he changed his mind. Then Lester Cowan, together with a group of theatre Owners, became seriously interested. It was just at this time that Lowell Thomas dropped in to see me. He had recently returned from Tibet and was filled with stories. Then, quite casually, he asked me what I was doing. I told him about Cinerama, and a few days later showed it to him. There was no mistaking Lowell's enthusiasm. He was all for it. He wanted to get the ball rolling immediately and, with Frank Smith and the theatrical producer Michael Todd, Lowell formed Thomas-Todd Productions. Frankly, I couldn't have been more delighted. Lowell was a showman, but not chained to the thinking, the superstitions, the inhibitions of the motion picture crowd. There would be no, "We can't do this because it has never been done before." Our first picture, with Cinerama as the only star, opened the eyes of the public to a new kind of motion picture entertainment. I like to think that it also opened their ears to a totally new kind of sound in the theatre. Their acceptance of both has meant a great deal to me. But I know that we can do more. Fred is still working on the development of the cameras and projectors, and on a number of new patent applications. I know how much more can be done with the sound. Used to present musical comedy or opera, it can give audiences a greater sense of "presence" than even a live show. We can create a wholly new kind of theatre. The potential powers of stereophonic sound alone can achieve a new entertainment form. Everything about Cinerama can be improved, made less expensive, made more effective. Its future as an entertainment medium, I firmly believe, lies completely in the hands of those technicians, engineers—and artists—who have been called upon to develop the potentialities that I know are within the process itself. The public has already demonstrated its willingness to support them. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|