Hollywood Comes to American Optical Co. |

This article first appeared in |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Written by: Roy C. Gunter Jr. News Science and Health Care Editor. From The Southbridge News Monday, October 14, 1985. Todd-AO Southbridge's Role in the Movies - First in a Series. | Issue 67 - March , 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On late night television, the viewer may

notice at the beginning of the credits of the scratched movie classic,

the words TODD-AO. AO, American Optical? In the mid-50s, Hollywood came

to Southbridge in the person of movie entrepreneur Mike Todd. Todd

wanted to make his mark on Tinsel Town, and he wanted America's top

optical firm to help him. Using some 100 of the sprawling Southbridge

plant's scientists, researchers and technicians, Dr. Brian O'Brien, one

of America's foremost optic experts, supervised the creation of a new

movie process: TODD-AO. On Oct. 10, 1955 - 30 years ago - that process

premiered with the showing of Rodgers and Hammerstein's

"Oklahoma!"

This is the story of Southbridge's role in the movies. |

Further in 70mm reading:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

The Showman and the Scientist |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

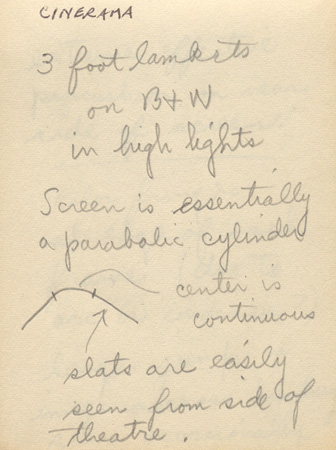

When Todd returned from a

European trip, he heard of the work Fred Waller was doing. Todd went to

Waller's place at Oyster Bay and saw the embryonic Cinerama, becoming

ecstatic about its possibilities. Todd was subsequently hired by Cinerama

and turned a simple documentary Lowell Thomas was planning into the

fantastically successful "This is Cinerama". Typically, Todd wanted

to take over this new medium. By October 1952 Todd became increasingly irked

by the technical difficulties with Cinerama. He was literally forced out of

the partnership by financial backers who were wary of Todd's financial ups

and downs. Todd, however, still believed in the widescreen principle. Thus

Todd asked Todd Jr.'s wife, who had friends at Columbia University, to find

out "who was the 'Einstein' of optics?" The answer came back: "Dr. Brian

O'Brien, director of the Institute of Optics at the University of

Rochester." O'Brien had a reputation for inventiveness and had developed

special lenses and high-speed cameras for A-bomb testing. With his own

typical speed, Todd immediately called O'Brien and asked him to come to New

York. O'Brien, however, said he was tied up but agreed to see Todd if he

came to Rochester. Todd said he would fly up and a meeting was set.  Walter

Siegmund's original notes from The Broadway Theatre in New York Walter

Siegmund's original notes from The Broadway Theatre in New YorkO'Brien, cautious as always, brought Walter Siegmund, a recent Ph.D. recipient who was working with him at the institute. The meeting took place in a restaurant near the airport. Todd explained that he wanted to develop a Cinerama-type motion picture system, but he wanted it to "all come out of one hole" - the three cameras and three projectors caused too much trouble. Todd wanted O'Brien to take on the job of developing the system on a consulting basis. But O'Brien said it was much too big for that and recommended that any of the three large optical companies - the American Optical Company, Bausch and Lomb, or Eastman Kodak - would be able to do the job. O'Brien, however, was interested in what Todd said about Cinerama and sent Siegmund to New York to look at the system. Siegmund went and reported back to O'Brien that while the optical system was not really sophisticated, the audience response to the wide screen was clearly favorable. When Siegmund was in New York he also took light intensity measurements from different parts of the screen with a Luckeish-Taylor photometer. When interviewed recently, he pulled open a desk drawer, showed the instrument and proudly said, "See - it still works!". Subsequently, O'Brien did go to New York. He agreed with Siegmund that optically Cinerama was not very sophisticated, but he also was tremendously impressed by the wide screen. His years in physiological optics told him immediately that it was the peripheral vision afforded by the wide deeply curved screen that gave the audience the definite sensation of not only depth but also of being a part of the action. After O'Brien had told Todd of the three optical companies that could do what he needed, he made his own investigation and selected the AO. Whether Todd knew that O'Brien had already made a commitment to Walter Stewart, then president of the AO, to come to the AO as vice president in charge of research is a moot point. But Todd's next action was typically Todd. Todd came to Southbridge to meet Stewart, plunked down a $100,000 certified check [$60.000, ed], looked Stewart and O'Brien straight in the eye and said, "Let's talk business!" Mike Todd Jr. relates in his book that Todd, having already become somewhat acquainted with the 125-year-old spectacle company, fully expected to see a Bob Cratchitt perched on a high stool when he walked in. The differences in the ways of thinking of a Broadway producer and entrepreneur and the cautious movement of the AO were enormous. Typical of Todd was what O'Brien called his constant spending rate - whether he had money or not. Todd himself said, "I may be broke, but I'm never poor." AO was just the opposite - steeped in conservatism in its business practice and its scientific outlook, it was, in fact, beginning to have trouble competing with more forward-looking optical companies - even in its own field. It is small wonder that it found dealing with the bullient Todd a different experience - to put it mildly. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The Protagonists |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brian O'Brien was born Dec.

20, 1898. His grandfather was from Killarney, Ireland, and his father was a

mining geologist at Queen's College in Dublin. The family emigrated to this

country in the 1890s and after the high school, O'Brien enrolled in an

electrical engineering program at Yale. After graduation from Yale in 1918,

he went on for a Ph.D. in pure physics. While he received his degree in 1922

he also took courses at Harvard and M.I.T. Avrom Goldbogen had a quite different bringing up. He was born on or about June 22, 1907 (the exact date is not known) and was the seventh of eight children of Chaim and Sophia Goldbogen. He was the first of Chaim's children to be born in the United States, the others having been born in Poland from which his family had emigrated. Chaim was educated to be a rabbi. As did the O'Brien family, the Goldbogens emigrated to America. Unfortunately, there was no opening for a second rabbi in Minneapolis where they settled and Chaim never did do well financially. He was a gentle studious man who eked out an existence officiating at kosher slaughterings. His son Avrom, however, was something else again. Because of a childhood friendship with a garbage man called "Toady," his friends started calling Avrom "Toady." Later this was shortened to "Todd" and much later because "Avrom" did not have a theatrical ring, Avrom changed his name to "Michael Todd." Todd's formal education was also not exactly that of O'Brien as it ended in the sixth grade when he was kicked out of school for running a crap game in the school year. He did, however, become something (of a sort) in academia that O'Brien never did - a college president. When he was 15 he saw that bricklayers were making good money, so he and a friend formed the American College of Bricklaying. Naturally, he was president. The school lasted only until the graduates found they were not really eligible for jobs after taking the two-week course. Todd took his money and went into the remodeling and building industry and by the time he was 18 had assets in excess of $1 million. Not entirely due to Todd, Todd's company, the Atlantic and Pacific Construction Co., went broke when his bonding firm folded. Down but not at all out, he started in the construction business again, and again in Chicago and again by his 21st birthday he had assets of nearly $1 million - about the time O'Brien was getting his Ph.D. from Yale. O'Brien also was showing his creativity early. Just one of the things he did later was to develop a special motion picture camera that would take 10 million frames a second. It was this work, in part, that attracted Todd to O'Brien. While O'Brien was working his way up the scientific and academic ladder, Todd was doing anything but standing still. For years Todd had had his eye on show business and in the late 20s he saw his chance. Building on his construction knowledge, he got a contract to soundproof the film stages for Columbia Pictures. Todd was now at last in Hollywood. On his 28th birthday he was well on his way to making his second million. Unfortunately the business folded and Todd was broke again. Todd's checkered but steadily upward career can be seen by the following sampling of his activities. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Upset by the technical

problems with three projectors and three cameras and the fact he could not

have full production control, Todd quite Cinerama. He went looking for a

system where "it would all come out of one hole" and with Brian O'Brien

found it. With the Todd-AO process a new era in show business was born. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Optical

Obstacles in Search of Bugeye Lens

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The overall technical

problem was to project a film onto a very wide screen without

distortion. Cinerama had gotten around the distortion problem with three

cameras and three projectors. To accomplish what Mike Todd wanted, a

wide angle lens with a field of view of 128 degrees had to be designed.

This was so a print could be projected to an equally wide angle and yet

be essentially distortionless on a deeply curved screen when projected

from the regular projection booth. To help with the technical work, Dr.

O'Brien talked Dr. Walter P. Siegmund, who was doing post doctoral work

at the University of Rochester, into taking a leave of absence. Dr.

Siegmund realized the challenge that faced him but still jumped at the

opportunity. He has been with the AO and most recently Reichert

Scientific Instruments in Southbridge ever since. The technical problems

were formidable just by themselves. But matters were complicated with a

man like Todd, who always wanted things yesterday, hovering about. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The Wide Angle Lens |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To understand the problem

facing O'Brien, basic optics must be considered. All cameras consist

essentially of a lens, a shutter, and a film plane. The problem is that as

the field of view gets greater, that is, as we can see over wider and wider

angles, the distortions on the film increase and increase rapidly. Dr. James

G. Baker tried to solve this problem for wide angle aerial reconnaissance by

using a lens that consisted of a series of concentric elements. The imagery

was indeed virtually perfect even for a field of view of nearly 180 degrees

but, and what a big but this was, the imagery was perfect only if the film

was on a hemisphere concentric with the lens. This will work well on, say,

an astronomical camera where we will take one picture and can then spend

months examining the negative. For aerial reconnaissance where the scene

changes rapidly or for motion pictures where we want many pictures of the

same scene in a short space of time, a hemispherical film poses impossible

obstacles in changing the film fast enough. Further, in going from

hemispherical to flat film without producing errors in angle or distance has

been proved impossible by the mapmakers. O'Brien's lens problem is now

getting clearer. We must not only see a very wide angle with the camera but

we must squeeze the image onto a flat film. One technique that has been

around for some time is the anamorphic system. This approach, which was

actually adopted by Twentieth Century-Fox in the fall of 1953, was rejected

by O'Brien. He said in a recent telephone conversation, "The trouble with

the anamorphic system is that if a crowd comes toward you, you always see

their faces head on whereas in actually they would appear in profile as they

pass." That is, it does not necessarily give the perspective of a true wide

angle lens. To augment the lens design capability of the AO, O'Brien hired Dr. Robert H. Hopkins of the University of Rochester as a consultant. AO had, of course, been involved with lens design problems for years and under people like Dr. Edgar D. Tillyer and Arthur Kavanagh in Southbridge and Robert Tackaberry and Richard Walters in Buffalo had built upon an envied reputation. Initially in Southbridge, as elsewhere, the work had been done largely with scaled-up versions of desk calculators. In 1953, in a move to update its lens design procedures, AO acquired first a card program calculator and then an IBM 650 computer. Both of these were monstrous by today's standards but they were just what Hopkins needed to design the complex "bugeye" lens, as it came to be called, for the Todd-AO camera. John Davis, now retired from the AO but still very active as an optical consultant, was manager of the optical computing facility. He relates that many a night he worked at the AO computer facility in Southbridge while it was connected to terminals in Hopkins' bedroom in Rochester and Richard Walters' office in Buffalo. Basically, the bugeye lens is a reversed telephoto lens. In actuality there were not three elements but 14. All of the surfaces had to be ground and polished and the elements then assembled with proper spacing. It is amazing that such a complicated lens could have been designed and fabricated so quickly. From the time Hopkins got the order to the time the lens had been designed, fabricated, tested and the patent filed was only a little over a year! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

AO

Researchers Find Solutions to Lens Distortion

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dr. Brian O'Brien was well

aware of the problems Dr. Robert Hopkins faced in trying to create a movie

lens at American Optical Co. for Hollywood producer Mike Todd. O'Brien and

Hopkins, rather than trying to create an impossibly perfect lens, elected to

accept some distortions from the lens - distortions they figured could be

taken out in the process of printing the film. The distortion they chose to accept in the lens was "barrel" distortion. Fortunately, this type of distortion in the negative is exactly what is needed if the image is to be distortionless when projected on a curved screen. Notice how the image on the film is curved. This is a deliberate curve to compensate for the cure caused when a normal image is projected on a deeply curved screen and viewed from beneath the beam. We have to be concerned, however, with more than the distortions by the wide angle camera lens. To give the illusion of depth through the allowance of peripheral (side) vision, we have to have a deeply curved screen. Further in a theatre the projector is usually mounted high above the heads of the audience. First the effect of the curved screen on the image projected perpendicularly onto the screen is to produce a pronounced droop in the horizontal lines. Try it yourself by shining a home slide or movie projector straight onto a piece of curved cardboard. If we now mount the projector above the plane perpendicular to the screen, we now produce a keystone effect in the vertical lines in addition to the droop in the horizontal lines. Researcher Brian O'Brien Jr. also noted that if you think about this further you will realize that unless something is done about it, normally more or less round faces at the ends of deeply curved screens are going to be distorted into ovals and look "pig-faced." This was one more problem for the optical designers who wanted to use the regular projection booth. We can now see, however, why the type of barrel distortion left in the lens was desirable as it counteracted the barrel distortion introduced by the use of the deeply curved screen. Dr. Walter Siegmund said there were three corrections made in the projection printing process: A-correction for barrel distortion in the vertical lines; the B-correction for droop, and the K-correction for keystone. The result should be a distortionless, perfect image when the picture is properly projected in a theatre. Arthur Kavanagh, now retired from AO Southbridge, designed the printing illumination optics while Henry Cole and Ian Crawford of the machine shop were deeply involved with the complex mechanical printing mechanisms. Dr. O'Brien, no slouch himself when it comes to machine design, suggested deliberately deforming the film onto a curved, slanted shoe with a vacuum back to further correct for the residual horizontal and vertical distortion in the printing lenses. This metallic show had to be of optical finish quality and this job fell to Colin Yates, then head of the precision optical shop in the research division. To achieve the ultimate corrections, it was necessary to have different corrections for each taking lens. O'Brien Jr. suggested using a line-by-line instead of a frame-by-frame printing with a cam mechanism to effect the desired changed in correction line by line. The AO projection printer was probably the most exotic film printer that had been developed for the motion picture industry. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The Camera Body |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It was one thing to make an

exotic optical system that would function beautifully in the clean, secure

environment of an optical laboratory. It was quite another thing to make a

camera that could be used reliably in the field. In fact, the camera got

perhaps its roughest test when it was hauled all over the world - up onto

roofs, down in boats, in cars, and trucks when Todd made his

"Around

the World in 80 Days".

The supervision of the camera construction fell on Henry Cole now working

with Siegmund at Reichert Fiber Optics in Southbridge. To add to Cole's

troubles, Dr. O'Brien had stipulated that to get all the detail he wanted on

the film plus to get the desired amount of light through the film gate, the

film had to be 70mm wide - twice as wide as the conventional 35mm film. 65mm

was to be used for image and pull down holes and 5mm for the six magnetic

sound tracks. Problems! Problems! There were no commercially available cameras like this to experiment with. Eventually Cole found that the Thomas Camera Co. had tried to develop a 65mm film camera but it had never been successful. O'Brien Jr., ever the successful ferret, did manage to scrounge up parts of several old Thomas cameras. These were turned over to the Mitchell Camera Co. of Hollywood, Calif., and were revamped under Cole's supervision. One of the problems, however, was the clatter involved in the mechanism reaching up and yanking down the 65mm film 30 times a second. Thirty times a second was the speed rather than the conventional 24 times a second to reduce flicker. The mechanism was bad enough but the noisy motor added to the din. Mitchell eventually solved many of these problems but even so he had to completely surround the camera with an elaborate sound-deadening enclosure appropriately called a "blimp." This is normally done with movie cameras but was particularly necessary for the more complex Todd-AO film. A standard Mitchell camera housing cost then about $15,000 but the Todd-AO camera with blimp cost $25,000. Consider that when a camera crew is shooting they always have at least one camera on standby, you can begin to see where the high costs of making movies comes in. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The Projector |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Faced with the virtually

impossible time schedule and the fact that there were no projectors for 70mm

film, Henry Cole and Hobart French, the latter then of AO Buffalo, found

some old Erneman projectors at Paramount. These were designed, however, for

65mm film. To accommodate the 5mm soundtrack, Cole and French came up with

the idea of using a separate normal 35mm projector in addition to the

Erneman and synchronizing the pair. John David was involved with the

projector as well as with the optical computing. He tells of the problem of

trying to install arc carbons 16mm in diameter in cooled silver jaws capable

of handling 400 amperes at 60V. Under normal times this is a problem but

trying to do it with the frequent power outages caused by the Flood of 1955

in Southbridge made it even worse. One time during the flood a hose broke

loose and 400 amps of electricity was essentially on the loose. Those were

trying times. Eventually contact was made with N.V. Philips of The

Netherlands and an agreement reached for them to design and produce a

projector

to meet the specific Todd-AO design. This projector was used in the world

premiere of "Oklahoma!" at the

Rivoli Theatre.

Just how close this whole showing came to failure was related by Norman

Powers. Powers worked with the movie people in the printing of the film. The

printing was done at Fort Lee, N.J. It was Powers' responsibility to set up

a laboratory where they could compare the film being shot in "Oklahoma!"

with that accepted as commercial quality. It was fortunate that such a lab

was set up as Powers caught what would have been some way off-color prints.

Powers also told about the convoy (Colin Yates was in it) that left Fort Lee

so late that they delivered the last reels of "Oklahoma!" while the

first reels were still in the projector! The final technical problem was that of the screen. The deeply curved screen that was planned for the Todd-AO system would require the projector's light to be spread out over almost twice the area of an ordinary theatre screen. Thus even with the special 16mm carbons Davis used, Dr. O'Brien felt there would not be sufficient screen brightness and directed that a new screen be designed. Ed Moon was in general charge of the project and Harry Crandon was the chemical engineer. The screen surface would consist of resin with plasticizer and loaded with aluminum flake. In theory the screen was to be embossed with a concave spherical imprint whose axis would change as you moved away from center screen. There were several reasons for this. One was to make the screen uniformly bright and another was to orient the spherical imprints so that light from the right side of the screen would not be reflected onto the left side of the screen with an obvious washout effect. The embossing of the special angled, spherical reflectors was great - in principle. In practice this was almost impossible to achieve well. The result of the best efforts that could be mustered in the time available were not satisfactory, according to Crandon. The experimental screens were streaky and there was an unsatisfactory spillover of light. Recourse had to be made to a specially selected commercial screen material suspended from an aluminum frame and tautly secured. Mike Todd finally had his system - on time as promised by the AO and "it all came out one hole!" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Mixed Reviews for "Oklahoma!"

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To start this section we

must turn the clock back to 1952 when Mike Todd first approached American

Optical. President Walter Stewart, after consulting the AO Board of

Directors, came back quickly to Todd with an offer. If Todd could put

together a group with theatrical prominence and the necessary financial

backing, the American Optical Company would work with him to develop the new

motion picture film process he envisioned. Todd was as good as his word and

assembled the following group called initially the "M-O-A-T"

(Magna-American-Optical-Todd) Corp. Later this was simplified to "The Magna

Corp." Leading the group were: Joe Schenck, chairman (20th Century-Fox);

George Skouras, president (United Artists); Judge James Landis, attorney,

and Professor Charles Seligson, attorney. Lee Shubert, Edwin Sneall (an

independent producer), Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein, and Arthur

Hornblow Jr. (film producer) were also board members. Todd had already sold

Rodgers and Hammerstein on the fantastic success that their "Oklahoma!"

would have when presented the Todd-AO way. That made assembling such a

knowledgeable and money savvy group much, much easier. "Oklahoma!" was as

American as apple pie but no one in the movie industry had been able to

capture the screen rights - Todd did it! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Even in Hollywood, where

the word "fantastic" is banal, the progress that this timetable represents

is "out-of-this-world." With make-shift cameras, projectors, and screens

O'Brien kept AO's word and Todd had himself, indeed, a unique motion picture

process. Todd, himself, however, had problems with his own kind. As Todd Jr., says in his book about his father, "He had automatically assumed that as father of the process and the whole deal, he would have control of the opening gambit, Oklahoma!" Ever mindful of Todd's mercurial ways, however, Rodgers and Hammerstein insisted on maintaining artistic control. Todd could make all the suggestions he wanted but the final word was to be theirs. The straw that really broke Todd, however, was the board of directors of Magna Corp., "His Board" gently, but firmly, sided with Rodgers and Hammerstein. There was too much at stake to trust to a movie industry outsider. The fact, however, that his name was now linked with Rodgers and Hammerstein and the Todd-AO process did give Todd new status in the film world - status that Aaron Goldbogen (Todd) wanted badly. He was un-broke again and status-wide on top of the world. On Oct. 10, 1955, "Oklahoma!" opened at the Rivoli Theatre in New York City. It was not the fantastic success Todd had envisioned. In large part this was due to serious scratches on the film that had been made when the normal method of editing the original negative was used. These scratches are not serious when the film is contact printed but when it was projection printed as in the Todd-AO system, very disconcerting streaks of light were produced. It is interesting to note that there were actually two projection booths at the Rivoli. The upper was the one normally used and the one for which the projection printer corrections were designed. A special booth had been built underneath the balcony so that film that had been contact printed directly from the original negative, and without the corrections required for use in the upper booth, could be used. The scratches were essentially removed later by a special lacquering process. George Skouras wanted to use the uncorrected film from the lower booth as the corrected film was not yet up to its potential. Unfortunately, the contact print film was not ready so they were forced to use the projection printed film for a few days. When the contact printed film was ready, the lower booth was used and the performance was markedly better - but the damage had been done. "Oklahoma!" in the Todd-AO process was a success but not as much of a success as had been hoped. Fred Hynes, now senior vice present of the present Todd-AO Corp. which does only post-shooting sound production, was one of the first sound men hired by Todd. When interviewed by phone, he was adamant that the difficulty with the early Todd-AO system was the poor quality of the AO lenses. In fact, Hynes stated categorically, "The 128 degree lens was worthless!" Todd Jr. also pointed out shortcomings of the lenses. There is some question of the correctness and/or objectivity of these criticisms by Hynes and Todd Jr. Interviews of the same Robert Surtees in the prestigious American Cinematographer (Oct. 1954 and April 1955) give the following quotations from Surtees: "The combination of the wide angle of coverage of Todd-AO lenses combined with the great screen area produces high on the screen. As a result, Todd-AO pictures are clearer and sharper." Earlier Surtees had said "from the standpoint of optics alone, Todd-AO is a superior picture process." Todd, however, while dismayed was not defeated. He believed in the process and now had a double reason for looking for another property. For some time Todd had been having a running battle with Henry Woodbridge, president of the Todd-AO Corp. Woodbridge wanted to mass market the Todd-AO system. Todd, on the other hand, wanted to select one theatre in each of the major markets, revamp it and make seeing a Todd-AO movie an event - an event people would drive many miles to see. Todd sold his stock in Todd-AO, resigned from the board of Magna and set about with determination to find a successor - an even more successful property than "Oklahoma!" It was on a trip to England that he visited a long-time friend and fellow entrepreneur Alexander Korda. Korda thought a bit and then suggested Jules Verne's "Around the World in Eighty Days." Todd realized instantly that this was the property he had been looking for. Further he already owned $40,000 worth of an Orson Welles version that had not panned out. Todd was off again! While there might have been some questions about the success of "Oklahoma!", there were none about "80 Days." As Inez Robb, a columnist with the New York World Telegram said, "Whoever thought we'd live to see the day when tickets to a movie would be as difficult to scrounge as those to 'My Fair Lady?'" On Oct. 17, 1956, "80 Days" premiered at the same Rivoli Theatre in New York City and was instantly a world success. Todd was acclaimed by all of the same movie moguls who he earlier felt he was an outsider, given rave reviews in the New York Times, the Herald Tribune, Daily Variety, Hollywood report, Time Magazine, etc. but the best was yet to come. Todd announced that he was to be married to Elizabeth Taylor, and they were the following year. Todd now had everything. Success. He had showed Hollywood he could meet and beat them; "80 Days" was named the picture of the year by the Academy of Motion Pictures, and he had married the person many considered to be the most beautiful woman in the world. And then suddenly it was all over - all, all over. On a flight in his own outdated Lockheed Lodestar that Todd Jr. had urged him to get rid of as a needless extravagance and unsafe to boot - Mike's plane flew into a mountain in New Mexico as it tried to go through a storm. His death was as turbulent as his life but Mike Todd with all his bravado, with all his mercurial manners will long be remembered - is still remembered in Southbridge as the man who caused the AO to fly - if even but for a few short years. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Remember "Oklahoma!"'s Premiere? Two Can't Forget

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On Oct. 10, 1955 - 30 years ago - that process premiered with the showing of

Rodgers and Hammerstein's "Oklahoma!". It's cold for October and they want

to sit near the window at a table dappled by the late afternoon sun. Walter

Siegmund orders ginger ale, Brian O'Brien Jr., a beer. Siegmund's words

tumble, roll, slide, loop from one thought to the next, finally stop when a

vivid memory pulls him up short. Then he clasps O'Brien's arm. "Remember?"

he says. O'Brien, a tall man who sits straight in a soft chair, lets his

large frame collapse a bit and leans forward. "Remember" he says, "who could

forget?" Siegmund sat separately in a darkened theatre, wearing a dark suit,

and significantly darker hair. Siegmund touches his full, white beard and

issues a sigh of comic regret. "Now I'm distinguished. But I really looked

quite handsome at age 30." O'Brien grins, reaches for a cracker. "And I was

thinner." On Oct. 10, 1955, the two were dazed from last-minute efforts to print a film the likes of President Harry Truman, Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher were sitting in a fancy New York City theatre to see. Hollywood's p.r. people may have tacked on the exclamation point because it looked impressive on marquees, but "Oklahoma!" from a technical viewpoint, deserved the exclamation point, say O'Brien and Siegmund. This was Todd-AO. Audiences, like never before, could enter the story along with the characters on the wide screen. That realization drove about 100 American Optical researchers, scientists and technicians to work one long day after another for 36 months. Oct. 10, 1955 was the climax ... sort of. O'Brien, 62, now a private consultant, and Siegmund, 60, a fiber-optics scientist at Reichert, were two background men among a roomful of glitter and glory. The excitement had been in the production, not the final product. Neither recalls if it rained or was clear, whether they drove themselves or took cabs to the theatre, whether their suits were black or blue. Both sets of eyes were scrutinizing the screen for technical problems and successes. Siegmund places both elbows on the table, presses his fingertips together. "If we had had more time ... the pressure was unbelievable. We got rushed into the process before we were ready. I hadn't slept for two nights in a row. The hour had arrived." O'Brien drains his glass. "I was mad as hell at those idiots! The stupid woman who edited the film." Brien O'Brien Sr., Todd-AO's mastermind, was, in his son's words, "thoroughly disgusted" that October evening. When the house lights went down and the projector illuminated the screen, scratches - deep, wide, hard-to-miss scratches - marred the picture. Siegmund was sandwiched between Director Fred Zinneman and film editor Arthur Miller. The credits were rolling down the screen. Then the streaks of light appeared. Zinneman leaned over Siegmund and whispered fiercely to Miller, "How could you give me a print like that?" "I'll never forget that moment. It was uncomfortable, to say the least," says Siegmund. "Idiots," repeats O'Brien, but more softly this time. "Quite frankly, it was trusted to a group of amateurs. I had dreams in college of becoming a technical expert in Hollywood. After Todd-AO, I think I came away with a little bit of disillusionment." "That cutter," says O'Brien, his voice loud again. "The extremes we went to handling the film, gloves and all, and that woman's carelessness. Damned scratches." Siegmund's words begin tumbling again and now O'Brien's speech comes faster too. The waitress brings another round but the two leave their drinks untouched for minutes. The sun has traveled past the table, hit the top of Siegmund's shoes and settled onto the carpet. "Forgive us," says Siegmund. "We have a lot of catching up to do about this. It was the most exciting time in my life, those three years. You're taking us a long way back. Is there something else we should be telling you?" O'Brien releases a small smile when asked what O'Brien Sr. thinks of dissecting a long-ago evening. "I talked to my father this morning and he wondered why I was wasting my time." "Now, now," says Siegmund. "I don't mean anything by that," says O'Brien. The two sit quietly for a moment. It's not easy, they say, to recall a swirl of emotions now three decades distant. "It was the most exciting period of my life, the climax, if you will. Everyone involved in that project loved it. But Hollywood was not for me. The optical scientists at American Optical were the best and that attracted me more than Hollywood," says Siegmund. "Once Mike (Todd) asked me if I wanted to live in Hollywood," says O'Brien. 'Hell, no,' I said. I'm sick of looking for stars in the rear view mirror." The two laugh long and loud. It is a good joke to be recalling extravagant movie budgets, nervous directors and Mike Todd's girlfriends in an empty restaurant along a quiet Main Street. "We could use a new project," says Siegmund. "Maybe so," says O'Brien. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 09-01-25 |