The Birth Of Todd-AO

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

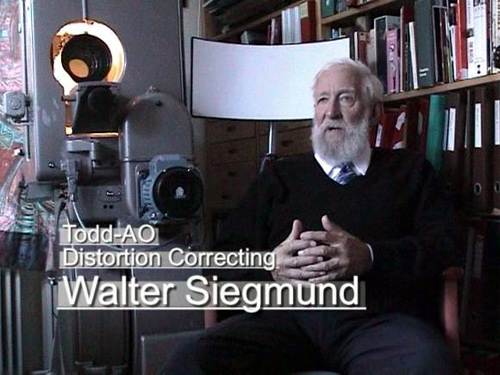

| Interview by: Thomas Hauerslev, Copenhagen, Denmark. Transcribed from MC audiotape and DVD between August 2003 and May 28, 2004. Edited for clarity by: Paul Rayton, Brian O'Brien, Jr., and Walter Siegmund. Clean up by: John Belton, Martin Hart and Daniel J. Sherlock | Date: 15 November 2005 |

Walter P. Siegmund: The 50th anniversary of Todd-AO and also

[approximately] of my employment at American Optical [AO] on February 6,

1953. Actually Todd-AO could be considered to have begun with the fateful

meeting in 1952 between Mike Todd and Dr. O'Brien at the Rochester (NY)

airport, where I was the silent witness. Walter P. Siegmund: The 50th anniversary of Todd-AO and also

[approximately] of my employment at American Optical [AO] on February 6,

1953. Actually Todd-AO could be considered to have begun with the fateful

meeting in 1952 between Mike Todd and Dr. O'Brien at the Rochester (NY)

airport, where I was the silent witness.Who would have thought then that movies would again become so popular and lucrative? Did Todd-AO make the difference? It would be nice to think so! Question: Tell me about your background and how you got involved in American Optical and Todd-AO. Well, I was both an under-graduate and a graduate student at the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York. The director of the Institute of Optics, where I took most of my training in optics, was Dr. Brian O'Brien. Dr. O’Brien was at that time very much interested in the field of physiological optics, which is the study of the eye. In fact that was his specialty. After I finished my doctoral thesis in physics, I was asked to stay on as a postdoctoral assistant, and one of the first things I worked on was a problem in physiological optics, an anomaly. It had to do with something peculiar about the detection by the eyes of flickering light (which, incidentally, sounds as if it has something to do with cinema). With black and white flickering lights you would find that, when they were in phase (for both eyes), the frequency has to be higher than if they were out of phase in order to eliminate the consciousness of flicker. This was known as “The Sherrington Effect”, and has to do with the way signals are passed from the eye to the brain. But if you use colors, complementary colors say like red and green, then according to the work that was done earlier, the reverse occurred, and that was the anomaly; it was not understood. It didn’t seem to fit anybody’s understanding of the process, and so Dr. O’Brien asked me to look into this problem again. I looked into it for some months; I can’t remember very well when; it was probably 1951 or 1952. It turns out that the previous measurements were in error and, that if you did it a little more carefully, it was consistent with the black and white phenomenon and so there were no so-called reversed Sherrington effect, which cleared up the problem. I don’t know if that impressed Dr. O’Brien, but in any case he was very pleased to have this problem resolved. Then, in late 1952 he approached me one day, quite by surprise, and said: “Walt, I’m going to go to the American Optical Company in Southbridge, Massachusetts to head up their R&D; would you be interested in joining me? Leaving the University and going there and working for me at American Optical?” I said I’d like to think about it and I thought about it for exactly 24 hours. I talked with Lois about it. We had been married then a little over two years. I said we would give it a try. He even went so far as to say: “Look if it doesn’t work out, I will arrange with the University so you can come back a year from now and just pick up where you left off”. Of course, it never happened and I stayed in New England and I’m still in New England. It was a wonderful opportunity; … one of our first problems we got into was Todd-AO. Question: Tell me about your visit to the Broadway Theatre and Cinerama – What was your reaction and who did you meet? First of all, Mike Todd had approached Dr. O'Brien. In fact I was present at that first meeting, which took place at the Rochester [NY] Airport. Some days afterwards he insisted that Dr. O’Brien come to New York to see the Cinerama process, but Dr. O’Brien for whatever reason, felt that he couldn’t go. Maybe that was his own way of being a little bit aloof. But in any case it was arranged that I should go in his place and make an evaluation; just to simply tell him “What did I think of it?” |

Further

in 70mm reading: Interview Reviews The Ethel O’Brien Printer. Letters from Walt Hollywood Comes to American Optical Co. Walter P. Siegmund, a small bio Todd-AO How It All Began Todd-AO Home Page In memory of Walter Siegmund |

Well the fact is, I can’t think of the exact timing, but I think I went in

the latter part of the day. I met with Mike Todd, Jr., in New York City,

and then he took me out to one of his friend’s houses somewhere outside

the city. Then we went back that evening to have a wonderful steak dinner

at a famous restaurant whose name I should remember [Peter Lugars]. They

served only steak and sliced tomatoes; they were famous for that I guess.

It was some of the razzle-dazzle that the Todds used, to soften you up, so

to speak. Well the fact is, I can’t think of the exact timing, but I think I went in

the latter part of the day. I met with Mike Todd, Jr., in New York City,

and then he took me out to one of his friend’s houses somewhere outside

the city. Then we went back that evening to have a wonderful steak dinner

at a famous restaurant whose name I should remember [Peter Lugars]. They

served only steak and sliced tomatoes; they were famous for that I guess.

It was some of the razzle-dazzle that the Todds used, to soften you up, so

to speak.The following day he escorted me to the [Broadway] theatre where I saw a demonstration of Cinerama. From the top, so to speak, but I was also given the privilege of going to any place in the theatre, observing from whatever location I wished. One of the few things Dr. O’Brien asked me to do was to measure the screen brightness, and he gave me an instrument, which was his own personal photometer, a very “ancient” instrument but also something that was very conveniently operated. I took a series of measurements of the screen brightness, as though that was really important. The important thing, of course, was the overall screen quality, and then the complexity of the system, all of which I reported to him in one form or another. But when I called him - and I think he asked me to do this - I did use the well-known expression “WOW”! And it was a wow-situation. No question about it, because at that time I was very intrigued with of all kinds of motion pictures, and to see this demonstration was very special. It was the best I’d seen of any motion picture, and “WOW” was a simple way to express that. What were your main responsibilities with the development of Todd-AO at American Optical? Well, it is getting a little hard to remember, but one of the things I was asked to do was to lay out the shape of screen precisely, with respect to the distortions that were contained in the wide angle Todd-AO lens. Once we knew exactly what they were, it turns out there’s a simple mathematical relationship between the shape of the screen, the position of the projection lens, and the distortion characteristics of the camera lens. But you don’t know those parameters until the lens has been completely designed. The lens was designed to try and create the desired depth of the screen, which I think was on the order of 13 feet, but we wanted to know what the exact shape should be. I remember doing those layouts in the drafting department of American Optical. Because I came with Dr. O’Brien, I was privileged to have sort of free run at the various facilities. It was a nice way to start a career - to have license to do things (anywhere). Everyone was very co-operative. I worked in their drafting department laying these screens out. Then the question was “How should the screen in fact be made”? How were current motion picture screens manufactured? We found out it was done by embossing plastic with a large number of very, very small concave spherical facets. Well, this worked very well with a flat screen, or one, which was very modestly curved, but our problem was the very deeply curved screen. If we had used that technology as it was available at the time, we recognised, that in a deeply curved screen, it would be necessary to modify the facets very substantially from those near the centre of the screen to those near the edge, in order that light which struck the screen would not bounce straight across the screen and wash out the picture. So, we attempted to devise a series of facets, which were tilted, in relationship to the distance away from the centre of the screen, so that every facet would return light towards the audience and not to the screen. 1) That was the concept; the question was “How could it actually be done? What kind of equipment would we need?” One of the people at American Optical´s Mettalurgy department, made an extraordinary suggestion. He said that it would be possible to make up the screen embossing rolls by embossing a piece of wire, which the company was using regularly for the manufacture of eyeglass frames, and embossing them in such a way that they could be wound on a drum to form a continuous pattern of slightly changing slant of facets. First of all it sounded like one of the very few ways one could do it, and secondly as something we could do ourselves at American Optical, and have complete control of the operation, rather than subcontracting, and seeing how it would work out. It sounded awfully good on paper. But we discovered to our dismay, as we went further and further into the process, that very minute defects were very pronounced on the screen. In particular, the repetition of the rolling embossing wheel, which made the facets, showed up periodically all through the screen, giving a wavy pattern which lent a texture to the screen that you wished was not there. The screen should basically be “invisible”. You should see only the image on the screen. The screen itself should not impose on your vision. We discovered when we projected still pictures on the screen that these defects were pretty well lost when you concentrated on the image, but as soon as the image moved, relative to the screen, the two “separated company”, so to speak, so that any defect from the screen remained fixed while the picture was moving. It ultimately proved that no matter how hard we tried, we could not make the screen free of those defects, which were intrinsic to the process, and it had to be abandoned. In place of the highly reflective facetted screen we substituted a screen made of ribbed white material with grooves impressed to reduce light from bouncing from one side to the other. This is a serious problem with a deeply curved screen - there’s always a certain amount of crosstalk, or cross illumination, which reduces the contrast of the image. But it was sufficient for the purposes, and it was done very quickly after we found we could not accomplish the higher (efficiency) reflective facetted screen. And the lower gain of the screen was acceptable. But we didn’t get all the things we had hoped for from the original screen. I was responsible for the work on the original screen, and it was one of my profound failures not to produce an adequate screen. But by that time I had been transferred to the problem of producing the optically corrected print and so others took up the issue of the screen, and were successful and therefore we did have a screen material that was uniquely Todd-AO. It worked, and was used for the opening and subsequent showings. |

|

Tell me about how AO organized the development of this huge undertaking

and how many people (and who) were involved. Tell me about how AO organized the development of this huge undertaking

and how many people (and who) were involved.Dr. O’Brien had just taken on the responsibility for running the Research and Development Department for American Optical. That meant he inherited a group of scientists and engineers who were already in place, some of whom were suitable for this kind of undertaking and some of whom were not. He also had pretty much carte blanche to hire new people because very quickly [a] number of new people was hired many of them from the University of Rochester. So we were able to bring in some new people to work on “it”. But in addition American Optical had not only a research department in Southbridge (in Massachusetts where the headquarters were), but also marvellous engineering facilities in the plant in Buffalo, New York. These engineers were accustomed to designing optical devices, microscopes, telescopes and binoculars - all those kind of things. They were ideally suited to manufacturing any kind of optical component that might be needed. In addition there were optical design experts at Southbridge that were accustomed to working primarily with ophthalmic lenses, but they knew lens design and therefore could switch their attention from ophthalmic lenses to compound lenses necessary for the process. So there was a lot of talent available. Additional talent was being brought in, in the form of engineers and scientists and so quite a large group of people were available when we started. Nevertheless despite that, the initial design work was done, in case of the (wide angle) lens, by Dr. Robert E. Hopkins of the University of Rochester Institute of Optics, who already had a significant amount of experience in wide-angle lens design. He had designed an even wider-angle lens for a different kind of wide-angle screen process years before and so he already had that as background, and he knew what the approach would be. In addition, there was a certain aspect of the design of the lens, which would require an aspheric optical component at the rear of the lens. The technology with which an aspherical lens could be produced had been jointly developed by American Optical and the Institute of Optics. In fact I had worked on that process myself, so I knew a bit about that particular aspect of it, but I wasn’t asked to work on it. Dr. Hopkins, in designing that lens, had the additional freedom to design the lens knowing it could include an aspherical component which would help correct the lens for all the conditions that were necessary for the best performance. Strangely enough the first optical design was only for the wide angle lens with the 128 degrees of field of view 2). Subsequently other lenses were designed, such as projection lenses, and narrower field camera lenses. In terms of the mechanical design, the work that was done later, on the corrective printers, also made use of some of the talents that were already in place in the research department, a group of design engineers who were accustomed to designing optical equipment. All they had to do was to get a new set of requirements specified and they were off to work on those. I think specifically of Henry Cole, for example, who is an excellent engineering physicist who understood the kinds of designs that were required. Some of the work was also subcontracted and wasn’t done at American Optical at all; the most significant being the [DP70] projector, but I’m thinking here of the correcting printer for which American Optical had the primary responsibility. Even some of the electronics for the printer was subcontracted, because we didn’t really have a lot of electronics background in the company. |

|

|

How many people were involved? Well at one time they talked about a hundred people. I don’t know if it ever reached that number, but it might have reached fifty. As far as names are concerned, well, they begin to fade a little bit. I already mentioned Henry Cole as an engineer who helped expedite the camera and later worked on the printer. Brian O’Brien, Jr. was heavily involved in this program. George Simpson, a very good friend of mine who just passed away (June 2002) was very much involved in the printer program. Dr. Charles Koester was another of the people who worked on it. In fact, when we were doing the actual printing in New Jersey, his wife also worked in the laboratory as well. It will take a while for me to try to remember all the names that were involved, but it involved a team in Southbridge, and at Buffalo, in the AO Instrument Division. The camera itself was a very specialized technology and, after working with a couple of old cameras that were found in the archives, new cameras were designed and developed by the Mitchell Camera Company, and that became the main source for the camera itself. We were not in the position to contribute technology for that. Mitchell was, after all, the world’s expert in that area. 3) The [DP70] projector, of course, represents a wonderful story by itself, and the coordination of the projector design was done again through the instrument division at Buffalo, New York. Mr. William Peck, who became my boss years later, was the person who coordinated that work with the Philips company in Eindhoven. Mr. Kotte was the engineer at that company who was responsible for that wonderful piece of equipment that you see behind me. |

|

|

How soon were the basics of the new process decided? How soon did you

come up with the principles of each component? It’s hard for me to recall that exactly, but I can remember being in the attic (the uppermost floor) of the Institute of Optics building and projecting pictures onto a screen, to try to get some feeling for what was involved in wide angle projection, and there was a feeling at the very beginning: How would we deal with the distortion of such a wide-angle system? How did we understand what was happening in Cinerama? And there was some confusion there, I think, until Dr. O´Brien pointed it out to us, (and I give him credit for that and he also got a patent on his concept). He pointed out that the natural distortion you will get from a “fish-eye” lens - which has barrel distortion that makes objects near the edges of the field more compact, more squeezed together than at the center - was precisely what you want to have in a lens if you are going to project onto a deeply curved screen from a fixed point behind the centre perspective with a distortion less lens. He saw this basic geometry and, once he pointed that out, in a way it fell into place. In other words, what the system demanded became an automatic feature of the system and in the design of a “fish-eye” lens you get exactly the kind of distortion that you need. Now, you can argue that is only (exactly) true from a single point in the audience, but in fact it spreads out enough so everyone can get a fairly good feeling for the perspective and a “sense of participation” that comes from it. But only one person is in exactly the right place to see everything precisely reconstructed by the projection system. Once this was established, then we were basically home free. We could have the deeply curved screen. We could have a fisheye lens - which is the only way to design a very wide angle lens anyway - and then the two were melded together. The projection lens system could be more or less conventional, and that was also a goal. When Mike Todd said he did not want to change a theatre, he wanted to be able to project in a normal fashion from an upper booth, then we knew that ordinary projection lenses would be appropriate. What remained - and what carries forward now to the correction of the residual distortions - is the peculiar shape of the picture as seen from the (usual) projection booth. When you have a deeply curved screen it does not look like a rectangle from the projection booth, and yet all frames up to that point were simply rectangular frames or square frames. |

|

Can you comment on the notion that Todd-AO was designed to reproduce

Cinerama. Can you comment on the notion that Todd-AO was designed to reproduce

Cinerama.We didn’t try to reproduce Cinerama - we made our own process. It seems to me that there were certain parameters, which more or less were expected. Something like a 2:1 ratio between width to height. It had to do with the width of a stage and the height of a proscenium arch, through which the screen in general would have to pass, and yet not project too far into the theatre. So there were some parameters dictated by theatre shapes, but we knew the wings of the screen would extend well beyond the proscenium in order to get the width. And also there may have been some sense that a 2:1 aspect ratio was reasonably favourable from a point of view of vision. It was not “slot” shaped like CinemaScope. This was a more appropriate rectangle to begin with, and then the question was - how much film would you want to devote to this? In fact what was the film to be, anyway? I think it was quite early on that a decision was made regarding this; in order to establish a new standard of sharpness for a large picture we needed to have more “real-estate” on the film. 4) It had to be bigger. So how could it be made bigger? Merely through width. Since many different widths had been used in the past this was probably dictated (and I am not quite sure how this were done) by the existence of some old 65mm equipment which allowed us to demonstrate some concepts early on, by digging up this old equipment and re-using it 5). I remember we found a series of projectors for 65mm film made by the German company Ernemann. We found some 65mm cameras made for the Thomascolor process, which had an 8-hole pull down that could be modified to a 5-hole pull down. 5 was established by the width and height parameters that I just mentioned, something like a 2:1 ratio. 4 holes would not have been enough (that’s a standard for the Academy 35mm film). 6 holes would have been excessive and would cost that much more in film. So 5 holes was the compromise. How all of this was done I’m not sure. I don’t think it was done necessarily in a large committee. I think it was done by a group of people just sitting together saying, “This is rational, why don’t we go with it?” And at a much later time it was decided that 65mm film would not provide enough space for the soundtracks, which were to be 6 magnetic soundtracks, so, it became obvious, (or, not necessarily obvious, but it seemed reasonable!) to extend the film width to 70mm for the release print, to carry the soundtracks. But there was no need to put 70mm film in the camera, because you don’t put the soundtracks in the camera. You put them on later, and so 65mm continued to be used in the camera and 70mm in the projector 6). And again, it was partly dictated by the availability of some 65mm equipment. If someone would have said, “Why don’t we make it 62,5mm”, and you would start from scratch, and it would be ridiculous. There might have been some other sizes around, but we didn’t know of them. Somebody in the system must have known about this existing [65mm] equipment, which was still stored away in the archives somewhere in Hollywood, and it was dug up. Didn’t you try to recreate Cinerama? This, of course, was the premise of the entire process. Cinerama had made a magnificent showing of a wide-angle system, but it didn’t have the versatility, for storytelling, which is one aspect. But the worst aspect was that it used up a tremendous number of seats in the theatre! It was very costly to install, requiring 3 projection booths, which at that time had to be manned separately - that was another cost factor - but the removal of a large number of seats, in the most favourable part of theatre, was in itself already a deterrent. It was simply very costly. What a theatre owner would like to do is to install the least equipment that he can use to get the full benefit of the system. The [original] upper booth was available since it was built in. Adding booths was an expensive thing to do anyway, because of all the installation and safety factors that had to be taken into account. The screen might not be that big an expense, although the owner would have to install additional sound equipment, but with those changes he would be in business in his own theatre as quickly as possible, with the least cost, which is a big factor for him. Cinerama, as I say, was a tremendous display of cinematic technique but it was a prohibitive process from a point of view of wide use of the process. I’m not sure how many Cinerama theatres of that type that I saw in New York were ever built, but it would have been a very costly way to proceed. At least that was how Mike Todd perceived it. |

|

|

What kind of person was Dr. Brian O’Brien? Any good anecdotes about

him? Dr. O’Brien was a scientist who was very precise in his scientific work and earned his reputation in three areas. He had worked in the area of nutrition, on vitamin D supplements for children, using ultraviolet light. He had done a magnificent job there, and he was also an expert in vision. But he actually had trained as an electrical engineer and he knew engineering extremely well. He was also the type of person who could discuss almost any subject, being a person with a fantastic memory, and a wonderful way of expressing his ideas. He was not reluctant to express his ideas. If anyone brought up a subject, he could almost invariably add some new elements to the discussion, so he was a great teacher. He was a very effective scientist. He was a good organizer. Dr. O'Brien, in my opinion, loved fieldwork where he would take a group of people out and do a project away from the school, or away from his home base. One of the areas had been in studying the distribution of ozone in the upper atmosphere, which he attempted to do in 1937, by attaching a spectrograph to reach what was then the highest-achievable altitude to a helium filled balloon. Well, there were some failures involved with that and he never got the information. But in 1948 when a new kind of balloon technology came along, he was anxious to renew those measurements and we - Dr. Parker Givens and I - brought home the necessary data from which he could conclude that, in fact, most of the ozone was higher than the maximum altitude that the balloon could achieve. He “had” made a tremendous contribution in World War II working with a team of people in the field of night vision, using a technology which is now totally obsolete, but at the time was the best available. And for that he received the medal of merit from the American government for having done such a magnificent job. Again, he had worked with a team of people, perhaps as many as 50, both students and teachers, who were reconfigured to do this kind of work. I was one of them, as a student at that time, also working in that field. But let me also say that, as well as being a good scientist and a good manager, he was also more of a showman than he would like to admit. He liked to present his material in an effective way. He was not just a typical, let’s say, college lecturer, who would tell what he had to tell in a dry manner. He had a way of making it exciting and I think, when he recognized this in Mike Todd, he realized that he and Todd could actually get along very well because they had some of that same interest. Todd was much more of a showman than Dr. O’Brien was, and much more aggressive. But they recognized, I think, this talent in each other. I enjoyed working for him enormously. He was a great person to work for. He also did something, which I can only just touch on briefly: He introduced the field of fiber optics in the United States of America. Now you might say, is that possible? Yes it is. It is a long story and it is a separate story, but one can say, almost as a quirk, he brought fibre optics with him when he came to American Optical, and a few years later it began to be developed. And it is still going very strong at what is now the offshoot from American Optical with the heritage that was developed as early as 1954 under Dr. O’Brien’s tutelage. |

|

|

How many years did he work for American Optical? I think his contract, when he joined American Optical, was for a period of five years. That encompassed all the work of Todd-AO, which was the first project he got into. Unfortunately, from my point of view, Todd-AO sort of got in the way of what might have become a whole series of even more important work. It just seemed so exciting at the time that, essentially, everything was dropped in favour of getting that job done as quickly as possible, because of its enormous potential for profit for the company. The fact that it didn’t achieve that, I think, was a problem for Dr. O'Brien - and a problem for the company - and my understanding is that he elected to complete his five-year period of the contract and then take up what might have been his “severance” from American Optical after the five years. In fact, in the last one or two years, he was not very active in the company. He did consult later on, in the field of fibre optics, and perhaps in some other areas, but I was only familiar with his consulting in fibre optics. Then he became very active in government work, and did that for the rest of his active life. |

|

|

“We selected the lenses to have some sort of distortion” – can you

explain that? Well, in a way I’ve alluded to that already, and that is when you design a very wide-angle lens, you have a couple of possibilities. One is to make it absolutely distortionless. Such a lens, for instance, is designed for aerial photography - for doing mapping. You have say, 90 degree field of view with such a distortionless lens, because you want the image to be an exact reproduction of what is viewed on the ground. Wide angle distortionless lenses were used for many years in taking architectural pictures and sometimes, and you may have seen this, used to take a picture of a large group of people, let’s say at a banquet or something like that. If you look at such a picture from the wrong perspective, i.e. looking at it from further away than the centre perspective, you find that, in fact, there is an enormous amount of distortion in such a picture. If you look at the image of a face near the edge of the picture it is completely distorted. It becomes a wide oval instead of a round [circle], or whatever it should be. And it’s really very ugly under those circumstances. So a truly distortionless lens on a curved screen would have resulted in serious distortions from the point of view of the viewers. But, beyond that, it is very difficult to design such a lens with a high optical speed, an F2 or something like that. Those older distortionless lenses were usually designed to be F16 or F22 with an extreme of maybe F11 or something like that. But never at very high speeds. If you want a very high-speed wide-angle lens it really has to be, what we call a “reversed telephoto” lens, or a fisheye lens. With a fisheye lens, you get barrel distortion. But we worried about that. We said - “What are we going to do about the barrel distortion”? As I said earlier, Dr. O’Brien finally realized that you want some barrel distortion in order to take care of the deeply curved screen in conjunction with a “distortionless” projection lens. And that is where the melding of the two came together. The reason that was fortuitous is because, now you can design a fisheye lens that was, let’s say, F2, so it could be used at low light levels. It could be a relatively fast lens and give excellent image quality, which is what it did. The big “bug eye” lens actually had superb image quality, but it also contained something like 15 or 20 lens elements in order to accomplish that. So it is peculiar that you don’t want a “distortionless lens”; you want a lens with a controlled amount of barrel distortion. Now the other side of that coin is that some of that distortion is not very desirable, in that it makes vertical lines near the edge of the field curve inward. Anyone who has looked at fisheye lens photographs will recognize that, and that it needs to be corrected. Fortunately, it is not as bad as it is for, say, a format like 3 by 2, because the vertical lines are not as long. But they are long enough to be troublesome! A telephone pole appearing near the edge of the bug eye lens is definitely curved. We dealt with that later in the printing process - that was one of the goals. I was involved, I think, in almost every technical discussion that took place, but not necessarily the business discussions. There was no need for that. It began to gain momentum. It started out with a group, maybe with the three or four of us at the very beginning: Bob Hopkins, Dr. O’Brien, myself, and a fellow named John Davis. He got in very early on. And some names I’ve already forgotten, people from Buffalo, got things going. We had quite a few people working on different aspects of it (he overall Todd-AO process). Once when we had at least one printer operating, the printing was done in New Jersey 7). It wasn’t done in Southbridge except maybe for some very early experiments. The printing of “Oklahoma!” was all done in New Jersey. After the opening of “Oklahoma!” (For which we made as good a print as we could up to that time) there was a lot of disappointment. Everybody trusted us to come up with a good print that would be very acceptable under normal Hollywood criteria. Well, I think, when this failed to happen, the first thing that happened was that they took the master negative back and used it to make contact prints and we never saw it again. But what they gave us was a duplicate negative that was made with internegative, and we continued working on that. And that was when I got more deeply involved in the printing process, and we were working on that, trying to make a better print. But the real problem was that we were doing it without any expertise in that particular activity, and it does take expertise to make a good print! We were kind of naïve about it, and, as a result it was a very time-consuming and very inefficient process. And then, after we found that we were stumbling around quite a bit, someone suggested that we bring in somebody who actually had some experience [printing]. And they helped us enormously to get an acceptable print. But we were still working with the duplicate negative. Now what happened with the prints we made I really don’t know. At one point, after we worked with the duplicate negative - after a period of about 6 months - I dropped out of it. I went back to Southbridge and that was it, as far as the basic process was concerned. But when I got back to Southbridge I undertook this other activity that I mentioned, using an optical solution to the distortion question and I did that on my own, without getting too many people involved, because I wasn’t sure it would work - but it did, and it looked like an interesting solution. |

|

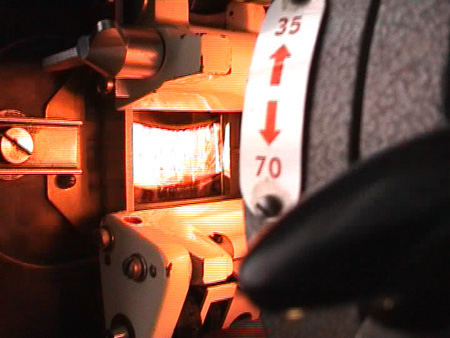

Side view showing the supply reels at the top and the take-up reels at

the bottom. The closed reels are for the raw stock and the open reels are

for the negative. The circular pulley in the center is the heavy flywheel on

the printing drive to insure smooth motion. Side view showing the supply reels at the top and the take-up reels at

the bottom. The closed reels are for the raw stock and the open reels are

for the negative. The circular pulley in the center is the heavy flywheel on

the printing drive to insure smooth motion.Tell me about the distortion correction printing process – how did it come about and how did it work. We recognized, very early, that if you were going to project from the upper booth you would have to make some optical compensation. You can’t just tip back the screen …You can ask. “Well, why not tip back the screen, so that the axis of the projector is perpendicular to the centre of the screen?” Well, that means tipping it back as much as 20-25 degrees, and so the image, as seen from the orchestra of the theatre, would look ridiculous! The horizon would go upward like a pan, you know, or like a dish, so that wouldn’t work very well. You want the horizon to appear level, at least from the point of view of a major part of the audience in the orchestra of the theatre. If people up in the balcony have to look at a line, which isn’t particularly straight, they may make an accommodation for it. In any case you have to decide where you want your best picture. And the decision was made: we wanted it to look like Cinerama, which meant that the horizon was straight for people sitting on the floor level of the orchestra level. And that was another way of looking at the question. Well, to do that with a curved screen meant that the image really had to look like the screen looked as viewed from the projection booth at 25 degrees, that means it has what we called a “droop” shape. I mean, it looked like an “upside down” smile. The curvature is substantial. If you project an ordinary contact print onto a deeply curved screen, with the screen strictly vertical or plumb, then you would get an enormously curved horizon on that screen. So that was one of the considerations. There were two further considerations that came along. One is that, in addition to the curvature, which we called the “droop”, you have “keystone” distortion which, if you again looked at the screen from the point of view of the projection booth, you realized that the bottom of the screen [-image] will be wider than the top and if you don’t correct for that, then vertical lines are going to be very, very slanted [kind of trapezoid] when seen from the orchestra part of the audience – so that had to be corrected. And finally, the third correction was for the fact that the “bug eye” lens (the 128-degree lens), would cause vertical lines to be curved due to the fisheye effect, and that had to be straightened out. So we had three kinds of distortions to compensate for projection from an upper booth, and the question was – how should that be done? Well, we played around with a number of ideas. I remember, in fact, I did some of the very preliminary work, involving using a lens to project a slanted object onto a slanted image plane, and so forth. And also another way of correcting the distortion due to the curvature of the 128-degree lens, of having a horizontally curved negative projected onto a curved print, sufficiently steeply curved using the adjusted geometry of the projection lens. Unfortunately, none of these things could be combined into one operation by simple projection. It took something more than that and, after playing around with some ideas, we hit on the idea that we would project each line element of the negative onto the print film with slightly different conditions which meant that the magnification of each line element, or each slit element, if you like, [is different] and the way in which you change the magnification is by moving the [printer-] projection lens back and forth along its axis, to either enlarge or reduce the size of that image for that particular line element at that particular instant. We had a cam-driven “relay” or imaging lens moving in synchronism with the motion of the film so that each line element of the film was treated slightly differently. And in that way, you could correct keystone, you could correct the barrel distortion (as we call it) and you could correct the barrel distortion not just for one lens (the “bug eye” 128 degree [effect, ed]), but also for the intermediate lens, which had half that field (64 degrees) and which also had barrel distortion. So you have in fact 3 different settings for the distortion. 8) Because the people of Hollywood said, - “we can’t work a story-telling movie with only the wide angle, fisheye lens – (128 degree lens), we need some narrower-angle lenses to tell stories, to get (good) close ups”. So this lens was designed to provide only a 64-degree field of view. That’s the full field, and then two other lenses were selected and mounted to provide two narrower fields of view, 48 degrees [55mm Zeiss, F2 Biotar double Gauss, ed] and 37 degrees [76mm Voigtländer or Schneider F2,8 Helior for 6x6 photography, ed], and those four lenses became the standard for the Todd-AO system. Regrettably, despite the fact that the whole system was supposed to resemble Cinerama with its 146-degree field, the Hollywood directors decided that this was unusable for storytelling purposes, and practically every scene subsequently done in Todd-AO was done with the narrower field lenses! |

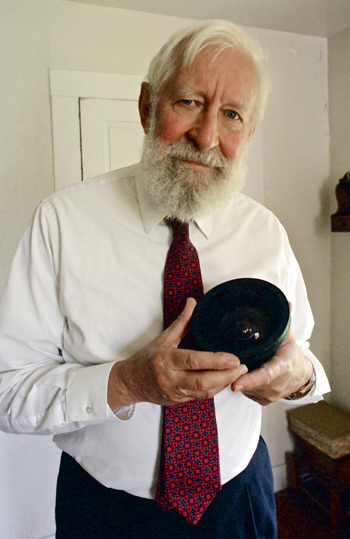

Todd-AO Equipment

Catalog, Distortion Correction Printer, Mark III |

So you might say the system was “compromised” almost from day one. So you might say the system was “compromised” almost from day one. But, I shouldn’t really call it “compromised” in the sense that it wasn’t an effective way of making movies. It’s just that it [using only the “bug eye” lens] wasn’t what we thought we were doing! We thought we were reproducing Cinerama, and what we were actually doing was putting more conventional movies on a very wide screen. But that still required that we develop the droop-correction process because of the requirement to project downwards at say 20 – 25 degrees from the booth. 9) Now, how was that printing really accomplished? I will give you some idea. You do it by imaging one line at a time, but in a continuous fashion, each line being slightly different from its neighbouring line for the full frame and then you start over again. In other words, the cam moves continuously as one frame is being printed and then it resets itself and starts over again with the next frame. And so the thing “clonks” along, moving the lens back and forth, back and forth for every single frame. And the trick was to make this run fast enough to make a practical printing process. How many printers did you have? We first made a “Mark II” printer, which was based on a slightly different principle, and it was the one we started with at the printing laboratory in Fort Lee, New Jersey. That was to get going, so we had something to show. Meanwhile, in Southbridge, three Mark III printers were being prepared and they were going to be run about six times faster, I think, than the Mark II printer. The “Mark I” printer was strictly an experimental unit and was never used for the printing of any part of the films that were shown. It was just an engineering model. The Mark II was set up as an operational model, but it was extremely slow. It would have taken months to make one print! And that was impossible. Those of us who were at New Jersey trying to get this system running were constantly in touch with Southbridge. “When can we get the Mark III printers?” Well, they finally did arrive, and they did speed up the process and we did get a print made in time for the opening [October 10, 1955], which had been scheduled previously for December 1955. I´d like to tell the story of what I probably should have done - since I happen to be that person (perhaps someone else was with me) who actually drove the first print from the New Jersey laboratory to the Rivoli Theatre. I would have done the whole system a great favour if I had stopped in the middle of the George Washington Bridge and taken that print and thrown it over the edge, and told them “There is no such print! Show a contact print!, and forget about the corrected print”. But I didn’t dare do that. But, looking back at it, it might have been a good thing to do, abandon that print, because it had serious flaws. Those turned up in the reviews that were printed the day after the initial showing. But it did have the distortion corrections that were called for. That part worked. It was little flaws, cosmetic flaws if you like, that spoiled the print. |

|

Did you attend the opening night of ”Oklahoma!” at the Rivoli and what

was the reaction to the new medium – any good anecdotes. Did you attend the opening night of ”Oklahoma!” at the Rivoli and what

was the reaction to the new medium – any good anecdotes.Yes I did. It’s vague in my mind now whether I attended the morning show or not. There was a morning showing on a Monday morning for the professionals and for the reviewers, which, incidentally, was unheard of. To get people to review a motion picture in the morning was an insult. They should have been shown the movie in the comfort of an evening, which was traditional. But someone decided to do it on a Monday morning. I think I might have been there for that, I’m not even sure I can remember. I know I was there for the official showing to a black tie evening crowd. You have to tell me when that was. It was October 13, 1955 But I do remember attending that, and it was a great event in that regard, but the print was still embarrassing. 10) What did [director] Mr. Zinnemann say? Where were you sitting? Well, it turns out, that was kind of special. I had the privilege of sitting with Fred Zinnemann and Arthur Miller, who was not the Arthur Miller of “Death of a Salesman” but another Art Miller, who had been hired to oversee the printing process at Fort Lee, New Jersey. And the three of us sat there together, watching the film. Fred Zinnemann really was very unhappy with seeing some of the glitches in the film, and he said to Art, “How could you deliver me film like that”? – or words to that effect. There was no good answer for him. I can’t remember what Art might have said to him, but I think he [Zinnemann] just felt the system had not been perfected and he was expected to work with equipment that wasn’t up to motion picture standards. Well it was, in a sense, experimental equipment, we have to admit that. That’s why I say it might have been better to “deep six” the entire print and tell them to go with the contact print. You might ask - “How can you go with a contact print from the upper booth?” - well you couldn’t, but there was a lower booth already designed and built into the Rivoli Theatre, so it could have been projected from there. |

|

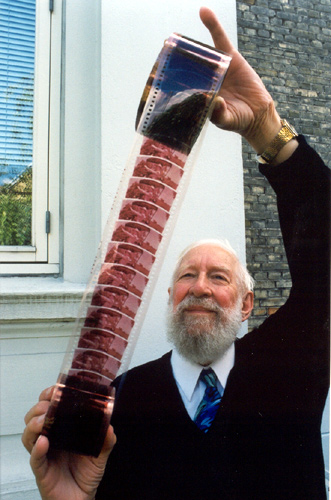

How many distortion corrected 70mm prints were shown other than at the

Rivoli Theatre in New York? How many distortion corrected 70mm prints were shown other than at the

Rivoli Theatre in New York?I don’t know, I’m sorry to say. I have no idea what became of the system after that. I was working on getting additional prints made after the initial “Oklahoma!” print, and then at some point it was decided that there should be other people involved in this. I think we turned it over to people with more professional experience. I was working, you know, with no background in the motion picture business at all. Let me tell you though, as a little sideline that, if someone had asked me in, say, in 1950, “What kind of career would you like for yourself eventually?" I would have said, “I would like to have been an optical expert in the motion picture business”. I would have “liked to have been”: and briefly I was (big smile). But after three years of Todd-AO I was glad to go on to something else. If we had been more successful, maybe I would have gone further with that activity, but I had very little contact with the motion picture business after that. I moved on to some other activities, including how to make gradient power eyeglasses, and things like that, which were more in line with American Optical company and then, as I mentioned, Dr. O’Brien had started the idea of fibre optics, and I actually moved into that and spent the rest of my career in fibre optics. Were distortion corrected 70mm prints available with and without striped magnetic sound? Oh yes, definitely. In fact, that print that we made and sent for the Rivoli I believe had been sound tracked…I take that back - because I don’t know when they would have striped it at the time; that must have come later. But I have in my possession, some corrected prints that have magnetic tracks. |

|

Was "Oklahoma!" shown at the Rivoli in 65mm with 35mm sound or was it

composite 70mm prints with sound? Was "Oklahoma!" shown at the Rivoli in 65mm with 35mm sound or was it

composite 70mm prints with sound?Well, I’m just guessing - that the first release was done with separate sound, because I don’t think there was time enough to get the film striped and recorded. We were delivering virtually at the last minute out of the laboratory. So they probably made other arrangements for the sound at that time. But subsequently I know that striping was done because, as I say, I have samples of some striped prints. But then again, I have to repeat myself, I sort of lost track of the whole process after that. Brian Jr. could probably give you more information about that, because he stayed with it a lot closer than I did, including, of course working with Mike Todd on “Around the World in 80 Days”, which I didn’t do at all. I had no further contact with Mike Todd at all. Tell me about the early presentations and Todd-AO test films. Where did you run the tests and what projection equipment did you use? No, I didn’t see any of the films being made but I will say that the company set up a theatre in Buffalo, New York, so that it would be near the plant where a lot of the components were being made and could be tested. We also had a half scale “theatre”, so to speak, at Southbridge in our own research laboratory. We set up a half size screen. The full size screen was built in a small theatre that was no longer being used, the Regent Theatre in Buffalo. It had a full size screen, as I remember and it might have been made of plywood and painted white. It was a place where they could make demonstrations, and of course they had a facility set up in Hollywood as well, for screenings, but the experiments could be run nearby in Buffalo, rather than sending them off to Hollywood. One other “theatre”, if you could call it a “theatre”, we set up was a screen-testing facility in the “powerhouse” of the American Optical Company. It was the only very large “room” that could take a 55-foot screen in the entire AO plant. And it could only be used at night, because the powerhouse had windows on all sides! Because I was responsible for developing the screen, I often had to run the Ernemann projector with test film to test the screens in that facility. Rather interesting in itself. |

|

What would Southbridgers think when they could see films at night

through the windows of the powerhouse? What would Southbridgers think when they could see films at night

through the windows of the powerhouse?They must have seen something or other “flickering away”. The old Ernemann projectors were remarkable, although they were simple compared with the Philips projector. They looked like they were made of LEGO sets. They were very simple projectors but they always ran. We also experimented with various sorts of arc lamps because, again, one of the hopes of the Todd-AO system was to get the screen very bright - because the Cinerama screen was very bright, with its 3 separate arc lamps illuminating the screen. We made Todd-AO to have a very bright screen, based on my measurements in 1952. Did you meet some interesting people? Todd, Rodgers and Hammerstein etc? I had the privilege of meeting all three of them, not very often, but Mike more than the others. I was present at the very first meeting between Dr. O’Brien and Mike Todd. He flew up from New York to the Rochester Airport. We met him right at the airport, and sat in a restaurant booth as I remember. I don’t know if anything was eaten at that time or if coffee was served. I’m not sure. He brought with him a person whom he had found who supposedly had some expertise in the motion picture field, but dropped out of the picture rather quickly. His name was Warren Millais and he had helped Mike Todd get in touch with Dr. O’Brien. 11) He really didn’t have anything to contribute after American Optical got into the picture, so I don’t think I ever saw him again. But there were the four of us together at that time. I was there primarily as an observer. I mean, it was a discussion between Mike Todd and Dr. O’Brien. He tried very hard to persuade Dr. O'Brien at that time, but Dr. O'Brien was not ready to make a commitment. It took some weeks, I guess, after that, to put the deal together. But American Optical had, I thought, a wonderful opportunity here to break out of its traditional lines into something new. They had tried to enter the field of television, believe it or not, at an earlier time. Projection television, but they were ahead of their time. Now projection television is really quite common. But they were maybe 20 years ahead of their time. They had worked really hard on producing projection television. What kind of work with the Todd-AO process continued after the premiere? I continued working at the printing laboratory in New Jersey for about 6 months and incidentally I might just explain the reason the printing laboratory was there. The printed film had to be processed, and it was processed at the Consolidated Film Laboratories, which also was in New Jersey, just a couple of blocks away. Art Miller used to run Consolidated Film Laboratories, but he left there to take charge of the printing of “Oklahoma!”. But even before it was completed, Art took a job at DuArt Laboratories in New York which is another film laboratory in downtown Manhattan. And so, towards the end of the period when “Oklahoma!” was being printed, Art was only there as an advisor, so we had to pick up the slack on that. And it was mostly Brian O'Brien, Jr. and myself who were responsible for getting the printing done. But I stayed on, as I say, working with the duplicate negative for a period of some six months, trying to get a better print than we had been able to get for the original opening. People were beginning to talk about other theatres for which prints were needed. But the whole process was cumbersome and slow and a different solution was really called for. |

|

|

Did you make corrected prints for each theatre? In principle yes, but as a practical matter, I think probably maybe only 2 or 3 different types were made. The principle difference is the angle of the projection onto the screen. I think in some cases they tip back the screen slightly anyway, but I’m not sure of that. I never saw any other installations other than the Regent in Buffalo, which I think, had a vertical screen. I don’t believe it was tilted. And the Rivoli, which had a vertical screen. As I say, I basically lost track of it about when that would have been. We are talking about some time in the middle to the end of 1956. |

|

|

Tell me about the time [1958/59] when American Optical (under Weldon

Schumacher) closed the Todd-AO activities – what happened with machines

and equipment? Well, I know that the laboratory in New Jersey was closed down earlier, because the printing machines were shipped back to Southbridge - the Mark III printing machines and the Mark II probably along with them, although it was no longer used. Immediately after the Mark III printers arrived they and the Mark II printer were put out of use. Anyway, those machines came back and they were stored for a couple of years. And then the word essentially came down, and I don’t know quite who or how it came down, but it came down - to the effect that those printers were obsolete and they were never going to be used again. And like a bunch of “vultures”, engineers and assistants “attacked” those machines to strip off what they thought were going to be useful components. And it was really a sacrilege to destroy those very nice pieces of engineering, just for their components! I wished at least one of them had been preserved so that it could have been put in the archives along with other old pieces of motion picture equipment. Sorry to say that it wasn’t. All we have left are the pictures, but we don’t have the printers. We do have a few of the corrected prints, including some that I have, and some that Thomas has. But the printers are gone. I do have a few, very few components from the printer. I wish now I had taken a box and collected a few for myself. I’m not even sure there is a complete set of drawings of those printers in existence any longer. But you do have the photographs, and Henry Cole and I can still tell you about them and perhaps also Brian Jr. The three of us can still describe what they did, and how they did it. But that may be the extent of it. |

|

|

Do you recall Fred Hynes? Yes I do, but Fred was primarily responsible for Todd-AO sound. I can say that at one time, we were in Hollywood and Los Angeles, and a group of us went to visit the Ampex Corporation, who were responsible for the sound system. The most unusual aspect for me is we had a luncheon date at a restaurant somewhere in Los Angeles, and just as we pulled up, I saw two of my neighbourhood friends from where I lived in Rochester, New York who were parking their cars at that time – I spoke with them. In that brief moment I was able to see them one more time before we separated our lives forever. I don’t remember too much about the sound aspects, except the decision to go with 6-tracks, two of which would be inboard of the perforations and 4 which would be outside the perforations. Of course, that whole concept of magnetic recording was really just getting underway at that time. I mean, I’m not sure how long that had been tried, but it was the obvious thing to do at that stage of development of Todd-AO, that is to go with magnetic sound. I was not very much involved in any of the sound work but obviously it had to be coordinated. I remember his [Hynes] being a very, very agreeable person. A person who was more of a problem for us was, from a point of view - what should I call it - a conflict between the real Hollywood expertise and our own almost lack of expertise - was Skip Sandford, the cinematographer. He rightfully, I have to say, identified the printing process as being a problem. A real problem, and he was concerned about it. And we had a demonstration at one point, and he said - “There surely has to be another way to do this”? It turns out to be he was absolutely right, but we hadn’t determined what that alternative should have been! I look back now on that particular incident very poignantly, because I realised that he said something which should have been the beginning of at least some re-examination of the whole issue of how to correct the picture for the screen. But we didn’t do it at that point. We kept a narrow focus on the printing machines, and it was not a total success although. It might have been perfected at some point. It was a lot to do in a short time. The window of opportunity for Todd-AO was also very limited, you know. If we had come a year later, by that time it probably would have been just lost in the “scuffle” of all the different processes that were being done at that time. |

|

|

Did you attend the first demonstration in Hollywood of the Todd-AO

process for the press? I don’t think so. But I saw some more limited demonstrations when I was in Hollywood briefly in 1954. It turns out that year both The Optical Society of America and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers were meeting on consecutive weeks. I was able to go out there for both meetings and during that time I think I saw some demonstrations - I mean some shots in the screening room at MGM which was the studio used for the production of “Oklahoma!” But it is a bit vague in my mind. The only impression I got at that time was that, probably, the most comfortable seats in any theatre I ever sat in were in that screening room (big laugh) at MGM, and not surprisingly. No, I don’t think I saw it for the press. I think it was only for a group of us privately. |

|

|

You mentioned you called Dr. O'Brien and said “WOW!" about your first

impression of the Cinerama process. When Todd-AO was finished and it was

delivered to big screen, did it live up to your expectations considering

you used the contact print and not the distortion corrected print? Was it

“The perfect show in Todd-AO” basically? (Long pause) We were so engrossed in trying to solve the problem of the corrected print that I think it was hard to become disassociated with that. We were working with a difficult process without the experience of the whole business. We ran into a problem, which we didn’t anticipate which was very, very worrisome. We found the master negative, which cost 7 million dollars to make as a film, had in fact been cut in the usual traditional way in Hollywood and was covered with scratches. That makes no difference in the world in a contact print, because the scratches are wiped out by the optical diffusion of that [printing] process. But when we made our projection print, every single scratch showed. It was suddenly a disaster, and we had to, very hurriedly, have a machine designed to coat the negative with a layer of lacquer to try to hide those scratches and that wasn’t completely successful even then. So, we were wrapped up in this kind of crisis of getting the film lacquered and then printed and so forth working against the deadline. I don’t think we actually were psychologically attuned to the idea of being able to step back and say - “Now, what do we think of this whole thing”? Those of us who were involved in the printing were, of course, and I speak for myself only, were very, very, uhh (big sigh), exasperated by the limitations that had been imposed on the whole effort. I told you about the scene of Aunt Eller that was off by “forty magenta” or something like that. I mean, what a horrible thing this was to see in the Rivoli Theatre, which had been completely rebuilt to produce the perfect projection situation. And there it was, you know. It was our fault; we had made a serious mistake. And there were all these cosmetic defects, too. Now, did the whole film have any impact for us anyway? I think we had seen it SO many times in making the various prints, trying to get a good print, that it was highly “diluted” by that time. On the other hand, when I saw “Around the World in 80 Days”, which I hadn’t seen anything of before, I was very much impressed. “Around the World in 80 Days” was a masterpiece of filmmaking, I feel. Both in the humour that was involved, and it was also technologically very good. It was as good as the process could be. It was projected in the Rivoli Theatre from the lower booth and it was a magnificent presentation. Everything clicked on the presentation of “Around the World in 80 Days”. And then, I think Mike Todd’s innovation of using all those cameo actors and then putting all the titles at the end was also a masterpiece. The man obviously had an incredible imagination and was willing to break with the traditional Hollywood very effectively. He must have walked away saying “I really showed them how it must be done, I really showed them”! But I never saw him at that time, so I don’t know what he might have said – but it was a great success, no question about it. I saw some other Todd-AO films too, but I can’t tell you which. Wasn’t “Porgy and Bess” done in Todd-AO? I think it was. I saw that in Baltimore and it was very good. |

|

|

After all these years, thinking back at that period of your life, how

would you describe it? It was the most exciting time, and it was exciting for a number of reasons. First of all, I told you the one thing I wanted to be when I was 25 years old was to be an optical engineer in the film industry. And here, I had an opportunity to do exactly that! And I mean it was such a wonderful fulfilment. But I didn’t want to be associated with something that didn’t come out quite right. But that is how it worked out. Still it was exciting, and when I talk to both Brian [O'Brien, Jr.] and Henry Cole who were there along with me, the three of us all agree it was the most exciting times of our lives. And it was because of the pace, and the people, the impact we could have made. The fact that we were dealing with something which was show business - as against something in the laboratory - that might emerge eventually. We were dealing with show business and, speaking personally, I was very, very interested in motion pictures anyway. I loved going to the movies, and this was the ultimate movie. |

|

|

And what is it like speaking about it 50 years later? Oh it’s fun, I enjoy it. And I may not tell the same story every time, but it’s pretty much the same. Let’s say I was disappointed because it lacked the nice touch of perfection, where you can walk away and say we were totally proud of what we had accomplished. I wished we could have said that - and we came close, came close. And it had an impact. I mean, it did affect motion pictures to some degree. But it was such a marvellous opportunity and we fell a little short, and that has always bothered me all these years. Maybe that is unfortunate to record, but I tell you the truth that is how I feel about this, and yet it was a wonderful time, a wonderful time. Those were my questions; do you wish to add anything? Well, I think I would add this, Thomas, and that is, it was incredible to me to find someone like yourself - who has as much interest in this as you have - and I am glad to be able to work with you and give you some of my personal recollections, my personal artifacts, that I saved from the process. And for you to bring me back to that period in the discussion we have had, the one we have just completed. No, I enjoy talking about it, I just wish I could say, - “It was a total 100 % success and it made millions of dollars” which people look for these days. But it may well be that the people who make wide film pictures now - and I don’t know if they make it in Panavision or other things… Certainly IMAX was just another order of magnitude more demanding than Todd-AO, but basically solved the same problems in their own way all over again. A big print film for high image quality, and lots and lots of light and nice wide angles... All the same philosophy was there, they just took it to another degree and were successful. But motion pictures, I think, in 1955, or maybe in 1952 I might say, motion pictures could have gone completely out of business. Theatres were closing at a tremendous rate. It was almost a dead issue with television coming in. But Mike Todd saw the opportunity with his friends with Cinerama and brought movies back to life. And today it’s still a tremendous, big booming industry. The number of pictures still being made today is just unbelievable. We see that when we go to video stores! Anyway, those were my comments. |

|

Notes: |

|

|

1)

We could not use the Cinerama screen concept with a single projector. Back 2) To simulate Cinerama's 146 degree optics Back 3) At that time 90% of the world’s motion pictures were shot on Mitchell cameras. They were chosen to first assemble the remaining Thomascolor cameras and modify them for the 5-hole pull down, and later to develop a new Todd-AO camera for the 65mm film. Henry Cole spent much time at Mitchell supervising this construction and development. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 4) Beside the sharpness reason (keeping the same magnification for twice as large a screen as standard 35mm films) we needed 4 times the gate area to put enough light through to maintain the screen brightness on the larger screen. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 5) Several years before, the Pullman Company had been forced by the government to sell their railroad sleeping car business. This left them with a large amount of cash, and they were looking for businesses to invest in. They engaged my dad to consult for them on a new color motion picture process called Thomascolor. It involved a camera with an image splitter to record three black & white color separation images on each frame of 65mm B&W film. These would then be recombined through red, green, and blue additive color filters and superimposed on the screen by the projector giving a full color picture. The present day monopack color films were in early development, so the future of Thomascolor did not seem bright. Pullman decided against investing, and the process never went anywhere. I heard a rumor about some wide film cameras being stored in a warehouse in Hollywood and immediately flew out there to investigate. Sure enough it was the old Thomascolor equipment. There was one complete camera, and parts for five more, a complete set of blueprints for them, a 65mm film perforator, edge numbering machine and a small film splicer. I immediately issued a purchase order for the whole collection and had it shipped to Southbridge, and that is how we started with 65mm film. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 6) The added 5 mm (from 65mm to 70mm) was added outside the 65mm perforations so both negative and positive would run on the same sprockets. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 7) Our printing laboratory was set up in rented space in Fort Lee, New Jersey to be near the Consolidated Film Industries film processing facility. They were a commercial motion picture printing and processing operation as a division of the old Republic Pictures Company. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 8) This - in fact, just today [22 June 2002], I brought Thomas this lens, which was the prototype of the 64-degree lens, which was designed by Dr. Robert Hopkins. Back 9) For trade secret reasons, we did not want details of our distortion correcting printing process to be known in the industry. Typically in the industry there were two types of printing. For special effects, prints were made on optical printers that printed one frame at a time, (step printing) with essentially a projector pointed into a camera with optics in between. This produced prints with transparent lines between the frames as in any camera. For production release prints, continuous contact printers were used where the negative and print raw stock were pressed together and run rapidly past a light source producing a contact print. In this case the clear frame lines in the negative let light through and so the print had black frame lines. While we let it be known that our printers were continuous printers (not step printers), in order to confuse the competition our printers had a cam operated shutter that cut off the light during frame line passage. Thus our prints all had clear frame lines, as though done on a step printer. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 10) The print was certainly embarrassing, but through absolutely no fault of ours. The negative we were given to print was so badly scratched it was unbelievable. Here was a piece of photographic film whose production cost was slightly more per mile than the eastern extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike over two million dollars per mile and it was destroyed by a union negative cutter. I watched her, over at Consolidated, take scene after scene, strip it off onto the floor, splice it and wind it up, floor dust and all. We did our best to rescue it by lacquering it, but this was only partially successful. Since we were projection printing (even though in a continuous manner) negative scratches scattered light out of the optical path and show up as white scratches in the print. With the conventional contact printing the light source is diffuse and the scratches don´t show. The process of scene by scene color correction is called “timing” in the motion picture industry. This is done by viewing a projected answer print and noting the amount and type of color correction filter needed for each scene in the printing process. At the insistence of the producers, the timing of the final print of “Oklahoma!” was done by a professional union timer from Consolidated. Therefore, any color correction errors were his not ours. As a result, the Todd-AO process was blamed for all the mistakes of the motion picture professionals, while our process itself was technically very successful. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back 11) I can fill you in on the subject of Warren Millais. As far as I know he never had anything to do with the motion picture industry. When I went to work for the American Newspaper Publisher´s Association research laboratory in Easton Pennsylvania, Warren was working there, not as an employee, but they had given him some working space. He had convinced some of the publishers (not your average technical wizards) that he had a process whereby he could take an old black & white photograph, or even a newspaper halftone, and reproduce the colors in the original scene. He tried to explain it to me, but when he got to the point of telling me that it worked by “the wavelength attacking the density” I sort of turned off. To this day I don´t know if he believed in what he was doing or was a complete four-flusher. The “process” consisted of unscrewing his enlarger lens wherever it would come apart (usually near the iris) and inserting a piece of cardboard with several strange shaped holes cut in it. Each hole was covered with a different colored gelatin. When reassembled on the enlarger it produced different colored blurs on the easel. By moving these blurs around he could produce colors in a scene, like a sort of a blue in the sky and a partial green in the grass, etc. After about a year the publishers decided he wasn't getting anywhere and kicked him out. Several months later I got a call from him asking how to get in touch with my father. He said Mike Todd wanted to contact him. Apparently he had somehow gotten together with Mike in New York. Mike was associated with Cinerama and was looking for an optics person to develop “Cinerama out of one hole”. Warren had heard me talk about my father, and one thing lead to another. Mike recognized what Warren was but he kept him on the payroll for about a year. He told me it was out of gratitude for getting him together with my dad. Brian O’Brien, Jr. Back |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 09-01-25 |

|