2018 Widescreen Weekend Introductions |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Feature film text by: -. Pictures by: Ulrich Rostek | Date: 22.10.2018 |

"The Greatest Showman" by Wolfram Hannemann | |

„Ladies and Gents – this is the moment you’ve

waited for!“ „Ladies and Gents – this is the moment you’ve

waited for!“With these very promising words a film musical opens which instantly took my breath away when I first saw it at a press screening in Stuttgart, Germany, last December. I had goose bumps all over me and tears of joy ran down my face. Lucky me that the projectionist had the house lights dimmed all through the end credits which meant that none of my colleagues was there when I left. It was that kind of movie I had long waited for. In fact director Michael Gracey is quoted saying that the movie is similar to WEST SIDE STORY, MARY POPPINS and THE SOUND OF MUSIC! With that in mind nothing can go wrong! It was a dream project for Hugh Jackman since 2009. According to Jackman, the seven year development process was, in part, due to studios' unwillingness to take a risk on an original musical. Nevertheless, after a slow start in the UK and Ireland, the film became an unexpected smash hit. Earnings in the 11th week of release increased 26% over the previous weekend, which is almost unheard of. Michael Gracey, who gave his directorial debut with THE GREATEST SHOWMAN, is convinced that no other genre would have allowed them to live up to the title THE GREATEST SHOWMAN than a musical – it gives one complete freedom to explore fantasy, magic and spectacle. When Hugh Jackman sent him the script, his instinct was to put together the film he believed P.T. Barnum would have made were he alive in the 21st century. Barnum was a visionary of his time, so it only was appropriate to design the film in the most forward-thinking way. Apart from pulling references from the great MGM musicals , Gracey wanted to explore how contemporary pop sounds and dance could elevate the story and make this period film accessible to a modern audience. Gracey says: „Hugh and myself felt really strongly about creating an original musical with all original songs, and that one decision meant years and years and years of work trying to find the right people. When we found Benj Pasek and Justin Paul, at the time they had only done an off-Broadway show which were not the credentials that anyone felt confident about. Except I knew that when I met them and I heard the first songs that they wrote for the film, those two were the perfect people to write something that is a nod to musical theatre but is also very heavily influenced by contemporary pop music. We wanted to sit somewhere in the middle. Some songs, because they’re narrative songs, tend to be a little more musical theatre because you’re telling a story within the song, but others could afford to be a little more pop, lyrically. People can say what they like about the film, but the music is exceptional. You can’t watch the film and wake up the next day without hearing one of those songs in your head. That to be was why we spent so many years writing and rewriting. To their credit, we were rewriting all of those songs again and again and again before we even had a greenlit film. There was no guarantee that their work was ever going to see the light of day, so I owe them everything because there would be no film if it wasn’t for the work that they did.“ Benj Pasek and Justin Paul, by the way, also wrote the songs for another film musical which we screened in this very auditorium during Widescreen Weekend last year and which became one of my favorite movies: LA LA LAND. |

More

in 70mm reading: Widescreen Weekend 2018 Gallery: Widescreen Weekend 2018 Widescreen Weekend Past Widescreen Weekend programs Creating the Widescreen Weekend Projecting the Widescreen Weekend Planning the Widescreen Weekend Cinerama, David Strohmaier and the "We have all seen it as a kid" thing in70mm.com's list of films blown up to 70mm Presented in 70mm Dolby Stereo Internet link: |

THE GREATEST SHOWMAN was filmed digitally with, among other gear, an Arri

Alexa 65 which is the digital equivalent of our beloved 65mm film camera.

Director of Photography Seamus McCarvey who created the stunning look of

films like the 2012 version of ANNA KARENINA or LET’S TALK ABOUT KEVIN,

says: „We had some fantastic sets, with very wide shots of the performers,

lots of extras and lots of detail going on, and the Alexa 65, shooting in

Open Gate ARRIRAW mode, was perfect for that.“. THE GREATEST SHOWMAN was filmed digitally with, among other gear, an Arri

Alexa 65 which is the digital equivalent of our beloved 65mm film camera.

Director of Photography Seamus McCarvey who created the stunning look of

films like the 2012 version of ANNA KARENINA or LET’S TALK ABOUT KEVIN,

says: „We had some fantastic sets, with very wide shots of the performers,

lots of extras and lots of detail going on, and the Alexa 65, shooting in

Open Gate ARRIRAW mode, was perfect for that.“.With regard to the aspect ratio, McCarvey says: „We shot widescreen 2.39:1 spherical, which we protected slightly for the IMAX versioning later on in post. We considered more vertical aspect ratios, such as 1.66:1 and even discussed 1.33:1, but when we saw the horizontal nature of the choreography, with 30 or 40 performers together in a line, the widescreen ratio proved a more natural fit.“ Asked about how the look for the film was established, McCarvey says: „Michael already had a very strong visual notion of the film, as he had been working on it for such a long time. He had created a range of digital storyboards and previzualised scenes to sell the idea to the studio. These were quite elaborate and took the visual look away from a photorealistic approach and more into the realms of theatricality, artifice and the magical imagination. They had a sort of handmade quality – the live action was to be blended with old-school, painterly backdrops, and other elements such as miniatures of the Manhattan cityscape. We didn’t look at any other films about Barnum and his life. Rather we talked about developing a Technicolor-based look to support the artifice. We considered the effect of the two- and three-strip Technicolor process on colour in movies such as AN AMERICAN IN PARIS, SEVEN BRIDES FOR SEVEN BROTHERS and THE ROBE. The idea was to take the real and transform it into this vivid, imaginative, magical Technicolor realm.“ The digital intermediate was done by Efilm at a resolution of 4K. The DCP which we are going to see was further enhanced by IMAX’s DMR process so that it still looks great on a very big screen like ours. However, the first generation of digital IMAX which is installed in here does only have a resolution of 2K. So we are in fact watching a 4K DCP on a 2K system. Nevertheless I personally think that the picture quality is still very impressive as is the 5-track sound which, by the way, was downmixed from a Dolby Atmos source. In an interview director Michael Gracey said: „It took so many years to make, that you kind of forget the joy of watching others experience it for the first time. Just in the last few weeks, seeing what people take away from the film, sitting in screenings where they don’t even know who I am, listening to their honest appraisal afterwards. It’s been incredible. To me the ultimate thing is if people leave the cinema humming a song from the film - that to me is real success.“ I would like to add a quote to Gracey’s comment. It comes directly from P.T. Barnum himself who once said "The Noblest Art Is That Of Making Others Happy.". And in this regard, I think, Cracey ultimately succeeded. Enough now of my strong German accent - Ladies and Gents – this is the moment you’ve waited for. |

|

“Grand Prix” by Dave Strohmaier

| |

How many of you saw it in 70mm

Cinerama? Anyone have home video release

of

"Grand Prix" 2011? Interesting short called “Style and sound

of speed” that includes interviews with race drivers, and “Grand

Prix” crew and even included someone named

David

Strohmaier! How many of you saw it in 70mm

Cinerama? Anyone have home video release

of

"Grand Prix" 2011? Interesting short called “Style and sound

of speed” that includes interviews with race drivers, and “Grand

Prix” crew and even included someone named

David

Strohmaier!This was a perfect film for single lens 70mm Cinerama and was the 3rd film in the MGM (4) film contract with a budget of 9 million. Others –“Ice Station” & "2OO1" in 1968 Super Panavision 70 was the format with 6 tracks magnetic so a flat 65mm image - not Ultra Panvision like “Mutiny” or “Khartoum” to fit Cinerama screens a slight bit of masking was added at the sides or in some Cinerama theaters the top and bottom of the screen had some cropping so it could be as wide as possible. The west coast premiere was held dec. 22 1966 at Cinerama Dome and played for 43 solid weeks. The day before that it opened in New York City at the Warner Cinerama. Highest ticket prices was 4.00 and cheap seats and matinees could be as low as $1.50. It was in the top 10 box office draw of the year (5th?). It won 3 Oscars, sound - sound editing - & editing. Acting nominations were for Jessica Walter and Antonio Sabato. My nomination as a 17 year old projectionist in Keokuk Iowa would have been Francoise Hardy - hands down! Even though she had only 10 lines of dialog. This was 36 year old John Frankenheimer’s first color film and 70mm widescreen film to boot his early career was at CBS directing live TV such as Playhouse 90 - over 140 live shows 1954 to 59. Then later Hollywood features: “Birdman of Alcatraz”, “Mancurian Candidate”, “Seven Days in May”, “The Train” and “Seconds” the film just before “Grand Prix”. “Seconds” was written by Lewis John Carlino, who would eventually become a director as well on his own script for “The Great Santini”. I was one of the film editors on “Santini”, and he told me he had the utmost respect for Frankenheimer - having worked and learned a lot on “Seconds” working together for several months. Note that all of Frankenheimer’s previous films were in 1:75:1 ratio and in b&w. For his first large format film, Frankenheimer wanted a real racing documentary feel on screen -- for this he asked graphic and film designer/concept man, Saul Bass to come aboard. Saul had been involved with such widescreen large format films as “Spartacus”, “Exodus”, "West Side Story", “North by Northwest,” and even helped Hitchcock with the thrilling shower scene in “Psycho”. On “Grand Prix” Saul would help the director, as a visual consultant, and even did some directing on some of the races. |

|

As you can imagine there was the danger that each race could look like

the others. So each had to have a different look, style and feel in its

approach. So this was one of Saul’s primary tasks. Example - watch for

the wonderful ballet sequence of racing cars where the music takes over

the sound track. Then there is the amazing optical effects -- like split

screens montages etc. This was hard enough with regular 35mm optical

work in the 1960s but now done in 70mm and the need to try and keep a

first generation film look for Cinerama. Saul bass supervised all this

as well in the complicated post production period. As you can imagine there was the danger that each race could look like

the others. So each had to have a different look, style and feel in its

approach. So this was one of Saul’s primary tasks. Example - watch for

the wonderful ballet sequence of racing cars where the music takes over

the sound track. Then there is the amazing optical effects -- like split

screens montages etc. This was hard enough with regular 35mm optical

work in the 1960s but now done in 70mm and the need to try and keep a

first generation film look for Cinerama. Saul bass supervised all this

as well in the complicated post production period. Today with digital computer editing - this would have been difficult enough - so imagine the difficulty in 1966, with all the trial and error. Although real race car driver Steve McQueen was to be cast in the lead - he stormed out of the first meeting with Frankenheimer. Probably realising that he could not control this director. So another actor and known race driver was cast as the main lead. James Garner (real name Bumgarner). Garner often said of himself “I’m just another racer forced to act for a living”. Frankenheimer was sold after that. Garner did quite a bit of his own driving in the film and at one point, during one stunt halfway through the filming, his car caught fire. Although unhurt - Lloyds of London immediately dropped his insurance policy on the film. So for the rest of the shoot – he drove with no insurance! Of course Garner was already a well known face from endless TV shows like “Maverick” - last year’s guest, Greg Orr’s father was in charge of that production. Some of you may remember his later hit shows like “Rockford Files” that Steven J. Cannell produced 1974-80. I worked as an editor for Steven on several TV shows 1983 to 88 and he would often bring up Garner’s name often as he was complaining about some actor in dailies “Why can’t this guy be more like Jim”? When “Grand Prix” came out McQueen, who was Garner’s neighbour, expressed regret to Jim that he walked out on Frankenheimer. So not to be undone - McQueen helped to get another racing film “Le Mans” off the ground for 1971. “Winning” with Paul Newman was earlier in 1969. All three racing epics were shown in 70mm 6-track in big cities with “Le Mans” and “Winning” shot in 35mm scope and blown up to 70mm. My co-presenter Hector Warr has another perspective on several other earlier racing films as well as “Grand Prix”. 91 year old actress Eva Marie Saint was our guest at last April’s TCM festival screening of “Grand Prix” at the Cinerama Dome and she said she had to close her eyes for most of the racing scenes. Kathryn Penny and I toyed with the idea of handing out seat belts for the races and to aid in getting you though the Cinerama motion effects off the curved screen. So if you are ready and have taken your Dramamine? Especially you brave folks down front - we now present to you in digital Cinerama the roadshow production of John Frankenheimer’s & MGM’s “Grand Prix”. |

|

"Grand Prix" by Hector Warr

| |

Formula 1 is typically seen as the pinnacle of

motor sport and "Grand Prix" matches its standards in cinematic terms.

It captures the racing thrill with stunning cinematography.

It captures the drama with personal conflicts on and off track.

It has love and it has tragedy. Formula 1 is typically seen as the pinnacle of

motor sport and "Grand Prix" matches its standards in cinematic terms.

It captures the racing thrill with stunning cinematography.

It captures the drama with personal conflicts on and off track.

It has love and it has tragedy.From its inaugural season in 1950 it took until 1966 to get the movie that Formula 1 deserved. Prior to Formula 1, Brooklands featured in the 1939 Will Hay comedy film "Ask A Policeman". In the final chase sequence Will Hay and his sidekicks are seen running around a rear projected Brooklands, dodging racing cars. A hint of what Formula 1 could look like on the big screen came in 1954 when Hammer films produced Mask Of Dust, released in the United States as A Race For Life. The film was directed by Terence Fisher, the man behind all three of Hammer’s first classic colour horror films Curse of Frankenstein, Dracula and The Mummy. Mask of Dust follows the story of once great driver Peter Wells as he struggles to regain his former glory. Fisher was a director who could get the most out of limited material and in Mask Of Dust he delivers a strong drama. Racing sequences were filmed at Goodwood but the actors drive against a back projection screen, looking like they are taking a pleasant drive in the country rather than driving full out on a grand prix circuit. The film only features two races, the British and Italian grand prix. The British grand prix features Raymond Baxter as race commentator. Baxter was an English broadcaster and prior to Murray Walker he provided commentary for the BBC in the 1950s and 1960s. Those of you who remember Raymond Baxter will also spot him in tonight’s film as a correspondent interviewing the winner at the British grand prix. Mask of Dust credits five drivers; Stirling Moss, Reg Parnell, John Cooper, Alan Brown and Leslie Marr. However, only Stirling Moss has a speaking part and it is a blink and you miss it speaking part. According to John Frankenheimer, the drivers in Grand Prix were modelled on real life Grand Prix drivers. James Garner was based on Phil Hill, Scott Stoddard on Stirling Moss, Jean-Pierre Sarti on a composite of Juan Manuel Fangio, Wolfgang Von Trips and Jean Behra. Grand Prix also gives far more screen time to real Formula One drivers with Graham Hill popping into a number of scenes through the course of the film. Father of Damon, Hill was a larger than life character well known for his Dick Dastardly moustache and derring-do. In the 1965 Monaco Grand Prix, the year prior to the season in which tonight’s film was shot, he pushed his car back on track after taking avoiding action up a slip road – and still won the race. He was a media star and very popular with the public. In his autobiography Life at The Limit Hill discusses his role in the film: |

|

Despite his prediction, Hill made it back onto the big screen for a brief role as a helicopter pilot in the 1974 adaptation of Alastair Maclean’s Caravan to Vaccares. Hill was also appreciative of the efforts required to make a film about Grand Prix racing on such a scale:

Indeed, the race sequences are unique.

The split screen segments show that life goes on even while the cars are being

raced hard around a grand prix circuit.

The racing is the central but not only aspect of a grand prix.

Frankenheimer said that he got the idea for the split screen and multiple images

from Alexander Hammid and Francis Thompson’s film To Be Alive, shown at the

New

York World’s Fair in 1964/65.

The film traced how children in various parts of the world matured into

adulthood.

It was shown on three separate screens, each separated by a foot of black space.

|

|

"Contact" by Carin-Anne Strohmaier

| |

Hello…. I’m delighted to be back to Bradford, the last time I

was here was in 2008 to introduce “Who

Framed Roger Rabbit” which was my first feature film with Robert

Zemeckis.

“Contact”

was my sixth feature with him and I have just finished my twelfth one. Hello…. I’m delighted to be back to Bradford, the last time I

was here was in 2008 to introduce “Who

Framed Roger Rabbit” which was my first feature film with Robert

Zemeckis.

“Contact”

was my sixth feature with him and I have just finished my twelfth one.In my career I have run into two type of film devotees at work - whose who love Robert Zemeckis' movies and whose who don’t - who would tell me “Forrest Gump” — too sappy —“Pulp Fiction” should have won Best Picture Oscar, “Back to the Future” — too juvenile” and so forth but then they will backtrack and say “except for Contact, that was a good one he did.” At that time “Contact” was considered his most adult film to date .. Ellie Arroway was no Marty McFly and the science in this movie was more science than science fiction, Hollywood style, of course. It was in 1979 that Carl Sagan and Ann Druyen who would later become his third wife, wrote the film treatment for “Contact” for Warner Brothers and there was immediate interest in the project. Everyone wanted another “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” but it stalled in development hell mainly due to changes in studio leadership. In the mid-80’s Carl gave up and turned his film idea into a novel which became a bestseller. Even though Warner Brothers still wanted to make this movie, filmmakers and writers involved with the project came and went — Roland Joffe was attached to direct at one point. Then George Miller was hired but after a long and expensive drawn out pre-production period, he was fired by the studio. And Zemeckis was hired after approving the rewritten script and was assured he would get final cut. it was shot on film and finished on film with the original cut negative — shot in 35mm, super 35, Vista Vision and 65mm. This was the first time I’ve ever worked with 70mm and everything about it was big - big to handle and needed to use big equipment. You needed big hands while I had small hands. The editing was done on the Avid digital system but we always maintained a up-to-date film print of the latest cut with lots of slugs for the missing vfx shots. Toward the end we went through 3 passes of negative cutting and I would get complaints from the negative cutters that you should only run two passes with the original negative or you could damage the negative. But we needed a film print for the Press Junket and then an updated new print for the World Premiere (which happened way before all the vfx shots were completed) and finally the final release version. Somewhere on this planet are prints of this movie with a lot of temp vfx shots. When it went out for previews before the final release date, it stayed out, they weren’t returned. I hope you won’t see it in this screening. |

|

We shot from September 1996 to early February - almost 6 months of shooting

with lots of location changes and had barely four months of post. After

principal photography wrapped, we were suppose to have 8 months to finish

but the studio wanted to make this a big summer event movie and moved up the

release date from late November to early July. We shot from September 1996 to early February - almost 6 months of shooting

with lots of location changes and had barely four months of post. After

principal photography wrapped, we were suppose to have 8 months to finish

but the studio wanted to make this a big summer event movie and moved up the

release date from late November to early July. But I was fortunate to meet Carl Sagan and his lovely wife Ann when we were on location in Washington DC. Growing up I had heard of Carl Sagan - he was a headliner in the 60’s and 70’s, making the cover of Time magazine in 1980 being hailed as “the Showman of Science.” Even if you didn’t know anything about astro physics, you heard of Carl Sagan and "Cosmos". Though what I had read about him was very critical of him and a lot about his ego and he was a publicty hound. So I was surprised when talking with him - I found him to be a very humble and cordial and amicable person with a sense of humor who was very excited to see his project come to fruition. This was definitely the best thing that I took away from my experience working on this movie. To have met Carl Sagan… This was in November … And less than a month later he was gone. He was supposed to have had a cameo in the film. I’ve often been asked about the opening shot in “Contact”. Carl wanted to be active in this production even though he was not in best of health, after all this was his baby. Before shooting started, he was in a hospital in Seattle for bone marrow transplant and Robert Zemeckis wanted Carl to sign off on the opening concept he had in mind but didn’t want to impose upon him at such a time. So like all good leaders, he sent his producer, Steve Starkey up to Seattle instead, and Steve said that Carl approved the concept but wanted to tell Bob this: “I can’t believe you have defied all the laws of Physics in your opening shot.” So with that in mind, I hope you enjoy this screening of “Contact” and thank you for supporting the Widescreen Weekend Festival. |

|

"Flatliners" by Rebecca Nicole

Williams

| |

Thank you, Kathryn and to the team, and thank you for coming out whether

you’re here for the entire Widescreen Weekend, Celluloid Saturday or just

this rare 70mm screening of Flatliners, which has been a long time in the

making. I discovered that this print exists within days of Widescreen

Weekend 2016, only for Sony to withdraw the film throughout 2017 in

anticipation of the remake, which came out exactly this time last year and

disappeared very quickly. Thank you, Kathryn and to the team, and thank you for coming out whether

you’re here for the entire Widescreen Weekend, Celluloid Saturday or just

this rare 70mm screening of Flatliners, which has been a long time in the

making. I discovered that this print exists within days of Widescreen

Weekend 2016, only for Sony to withdraw the film throughout 2017 in

anticipation of the remake, which came out exactly this time last year and

disappeared very quickly. Flatliners was controversial well before it came under the scrutiny of the medical community. Uber-producers and bidding wars defined its era, and Scott Rudin found himself the most reported on person in Hollywood when he bid for Peter Filardi’s screenplay against Columbia, with whom he already had a multi-picture deal. Rudin had learned about the script from a Columbia executive and was alleged to have bought another script during a Writer’s Guild of America strike. After two weeks of “wrangling” Rudin left Columbia and Flatliners reverted to Michael Douglas and Rick Bieber’s Stonebridge Productions who had a three-year, three picture deal with Columbia of their own. Rudin retained an executive producer credit. Douglas, being Douglas, never commented on the matter. Peter Filardi was a 26-year-old graduate of Boston University, encouraged by friends to move to Los Angeles after becoming the veteran of two unproduced spec scripts for Miami Vice and an episode of MacGyver. Earning a living through TV commercials for telephone sex lines, Filardi started writing Flatliners in 1988 after the experience of a friend who had lain on the operating table technically dead for 90 seconds. The film’s principal themes were drawn from a buzzword of the Irangate scandal: “accountability” and the material expectations of his generation. “It’s essentially an adventure movie,” he said, “The west has been done, space has been pretty well charted, and it seemed as if the only frontiers left would come from within ourselves.” Sending out his finished draft to 4 or 5 producers, within a week 10 were interested. Bidding started at $10k. Scott Rudin bid $400,000 for it. “Unlike St Elmo’s Fire these students are highly competitive,” said Schumacher. “It takes their near-death experience to soften and bond them. They view their dangerous experiments as an easy way to fame and wealth, yet death brings their blind ambition to its knees.” For the director the theme resonated having just come from filming a weekend event for people with various stages of HIV at the Centre for Living in New York. Saturated by discussion of the fear of death, amends and the completion of relationships, Schumacher signed up to direct Flatliners before he finished reading it. Researching from hundreds of books Schumacher observed that “suicide attempters report horrible experiences, and this is what the Flatliners technically do. I wanted to give it a sharp ironic edge, because if you screw with death it screws you back. The purpose of Flatliners is to give you a visual and visceral experience that you haven’t had before in a movie.” Starburst proclaimed “Flatliners has the most exciting visual look any film has dared to present this year”. The opening, continuous, 35 second helicopter shot firmly establishes Kiefer Sutherland as the head of this new band of Lost Children and the recurring themes of Schumacher’s early Brat Pack hits. Incorporating half the giant head of Mercury, a painting of Prometheus, a combination of Greek, Roman and Renaissance art and a vivid Halloween sequence Eugenio Zanetti’s production design was either praised as high concept Hammer or dismissed as MTV gothic. In interviews Schumacher enjoyed recalling a hospital attendant in Miami who asked him “Where was Flatliners shot? Rome?” Principal photography began in Chicago on 23rd October 1989 with a 15 million-dollar budget. 12 Chicago locations were used, including Loyola University’s Lake Shore Campus for exteriors. The Museum of Science and Industry plays the Taft building. The production then moved to three soundstages at Warner Bros in Burbank where an iron grid floor was laid so their images of the underworld could be lit from below. The shoot lasted 57 days, with remaining exteriors shooting on the Columbia lot. Principal photography wrapped on 22nd January 1990. Schumacher told Jan De Bont to make Flatliners look like an action movie. “It’s the content shaping my form,” Schumacher said, “not the style. Instead of having Flatliners come across like a special effects film I went for an unusual and distinctive look. Sometimes we’ve got 65mm, 35, 16 and 8mm footage going off all at once that makes the journey into death fun and visually fascinating.” Make-up effects were created in camera by Greg Cannom and Ve Neill. Quantel Paintbox editor Steve Purcell assembled some rough effects on video which Schumacher liked and transferred straight to film rather than recreate. A sequence going into someone’s eye was created using the then state of the art “Harry” effects compositing system. Shooting what the crew dubbed the “Descent into Hell Sequence” the production manager got a little worried. “He said he’d never had to use so many different colours of gels in any movie he’d ever worked on before,” said Jan De Bont, who shot most of the film’s anamorphic Panavision footage himself handheld. The sequence uses five locations, beginning with a long lens dolly move cutting to a crane shot as Nelson lights a cigarette. As he enters the second location the camera goes from 24fps to 30, 36 and then 40fps drawing us into his nightmare. One camera dollies behind him with a parallel Steadicam capturing his point of view before turning back in on him. Murals feature prominently in Schumacher’s aesthetic and the next location in the sequence features the work of LA street artist Julian Ingals. The opposite wall is covered in polyester film Mylar for blue sheen. “The stairs look strange,” De Bont described the subway used next, “because they’re blood red contrasted by fluorescent lights with blue gels and a water slicked floor.” After night shoots finished the sequence was completed at one last location, a 60-foot-long tunnel on the railyards side of downtown LA. Despite the nightmarish storyline and images, Julia Roberts enthused that “Joel created such a warm working set that everyone wanted to do their best for him and his vision.” Kevin Bacon habitually made Roberts break into her infectious laugh, making it hard to do serious scenes, the fun and games shocking the Jesuit fathers of the campus at Loyola. Flatliners opened on 10th August 1990 playing in 70mm at the Odeon Westwood, the AMC Century City and Grauman’s Chinese. The press focussed firmly on the ill-fated engagement of Sutherland and Roberts, and a woman who passed out at the premiere, although this turned out not to be related to the film. On 35mm Flatliners was the debut of CDS (Cinema Digital Sound) while 70mm blow-ups came with 6 track. In the UK Flatliners played in 70mm at the Odeon West End. What we’re about to see may be the very same print. Variety reported an opening weekend of over 10 million dollars, and a final domestic total of $65 million. The LA Times called Flatliners the “hottest movie in town”, The Episcopalian News said it “may even accomplish some evangelising of its own”, and The Hollywood Reporter wrote “one could service several hundred werewolf movies with the amount of steam that rises from this set.” Flatliners 2 was announced in a Variety article on February 4th, 1991 but never materialised. 2017’s reboot featured Kiefer Sutherland but in a different role, disappointing many fans. During the filming of Flatliners a San Diego doctor was arrested for faking near death experiences on patients whose hearts he would stop, just like the students do. Schumacher responded to one interviewer on whether someone might imitate the Flatliners with a look of complete blankness. “Well…” he considered, “Maybe someone insane….”. On whether Flatliners contains a deliberate homage to Don’t Look Now, Schumacher explained that the original costume to be worn by a key character was a dark suit, but that this blended into the backgrounds so a convenient red hoody floating around the costume department was picked for contrast. “But having thought about it a lot, I’m sure it was somewhere in the recesses of my burnt-out brain,” he speculated, “Both films feature spiritual and physical karma and both feature scaffolding. I’m just a demented old director at work. If you see in my next film a camel going across a desert with a man in white clothes on chances are I’d forgotten I saw Lawrence of Arabia.” I hope no-one here tonight has just woken up after last year’s closing 70mm gala of "Lawrence of Arabia". But if you have, I’m Dr Williams and I’ll be here again at 9:30 with Michael Cimino’s comeback Year of the Dragon. But now let’s plug in and take the 70mm trip that is Joel Schumacher’s original blockbuster: Flatliners. |

|

"Year of the Dragon" by Rebecca Nicole

Williams

| |

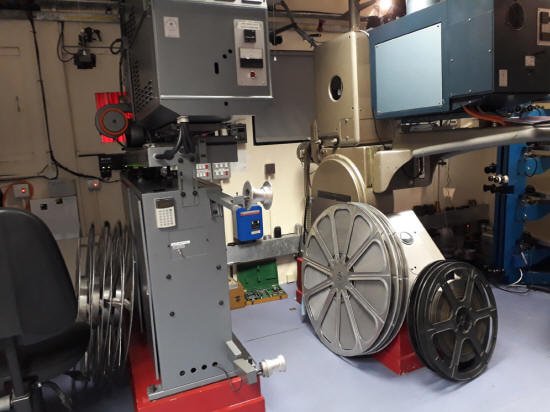

Thank you again, Kathryn and I’d like to take a moment to thank the

projection team up in the booth for whom this has been a big day. How about

we give it up for the projection team? Thank you again, Kathryn and I’d like to take a moment to thank the

projection team up in the booth for whom this has been a big day. How about

we give it up for the projection team?And welcome back, if you were here in Pictureville just now for that fantastic screening of Joel Schumacher’s Flatliners and if you’ve just joined us a simple “welcome.” If you’ve just woken up, I’m Dr Williams and we’re moving on to another cult director and one of his most notorious works: Michael Cimino’s “Year of the Dragon”. Cimino was a great widescreen director, shooting all seven of his films in the anamorphic 2.35:1 ratio. Born in New York City in 1939 he studied fine art at Yale before becoming one of Madison Avenue’s top commercials director. Moving to Hollywood in 1971 he said that the only way to become a director was to own a script that a star wanted to do. Clint Eastwood bought Thunderbolt and Lightfoot intending to direct but was so impressed with Cimino he let him work on the script for Magnum Force eventually up the directing reins on Thunderbolt and propelling Cimino to the A-list. By the 1980s, however, Cimino had ended the New Hollywood era of American auteurs with Heaven’s Gate going several times over budget, taking years to complete and becoming a box office disaster that nearly bankrupted United Artists. Between 1981 and 1984, Cimino was attached to several projects including Footloose, which he envisaged as a musical Grapes of Wrath, causing Paramount to panic and replace him with Herbert Ross. Cimino has been likened to directors such as Howard Hawks, John Ford, King Vidor and Roberts Altman and Aldrich, for whom myth often comes before psychology. One critic compared Year of the Dragon to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, where the great American hero is forced to act irrespective of whether he gets any credit. Easy Riders Raging Bulls author Peter Biskind called Cimino, with his themes of what it means to be an American, “our first home grown fascist director, our own Leni Riefenstahl”. Dubbing Cimino’s eventual comeback “Hell’s Gate” Nick Roddick wrote in the March 1986 Cinema Papers that it was “amazing Cimino was able to make another big budget film post Heaven’s Gate. Less surprising that it is under the aegis of Dino DeLaurentiis, who has the gambler’s instinct of a true impresario.” Principal photography started on 27th October 1984 on an immaculate recreation of New York Chinatown at the DeLaurentiis studios in North Carolina, one of the largest street sets ever built. Director of photography Alex Thomson operated his own camera, shooting mainly handheld in Joe Dunton's anamorphic process J-D-C Scope. Cimino reportedly brought the production in on time and on budget. When completed the film’s politics immediately came into question. Cimino said Year of the Dragon had “been described as a sort of sequel to The Deer Hunter, as if Robert De Niro’s character were 8 years older and had become a New York City cop”. Finding its place amongst the movies of the time that had sparked huge outrage, Year of the Dragon was quickly nicknamed “Rambo in Chinatown.” As Mickey Rourke’s character, Captain Stanley White, says in the film: “This is Vietnam all over again. No-one wants to win this thing.” Picket lines formed in Hollywood, Washington, Boston and Detroit. Protestors distributed leaflets. Press conferences were held in New York and San Francisco. Outside Loew’s Astor Plaza in Times Square over 200 demonstrators announced the boycott. The Coalition Against Year of the Dragon had formed between seven bodies including the Organisation of Chinese Americans, the National Asian-American Telecommunications Association, and the Chinese Benevolent Association. Feelings were strong about the tide of anti-Asian movies such as First Blood Part II and Cimino’s own Oscar winner, The Deer Hunter. Soon Year of the Dragon screenwriter Oliver Stone would spearhead a new cycle of films about the Vietnam war which would last at least half a decade and include entries by filmmakers such as Stanley Kubrick, and Brian DePalma. The deranged Vietnam veteran became a “thing” in action movies like “Lethal Weapon”. “I was in ‘nam, man” became the 80s equivalent of a meme. Robert Daly, whose novel had been greatly altered, issued a statement against the film: “I deplore the violence and racism in the film. I tried to show that the Chinese were as good as any other human beings, who suffer, and care, and bleed like anyone else. This portrayal is horrible.” When Year of the Dragon opened in Manhattan on 16th August 1985 it was top of the box office. Playing in 982 theatres, it took over $4 million in its first 3 days. John Lone, alumnus of the Peking Opera, defended the film, comparing it against the Suzie Wong and Charlie Chan depictions of old. |

|

MGM/UA issued an unsigned statement reading: “We believe the claims made

against the film Year of the Dragon are without validity. Regardless of our

opinion, however, we encourage members of the Asian community to view the

film and make their own judgement”. Within a week the coalition represented

fifty organisations and had some demands: “MGM/UA should provide employment

for Asian-American actors in movies that portray Asians with accuracy and

sensitivity. The price of employment in this movie is the perpetration of

destructive and demeaning stereotypes.” Variety reported that, ironically,

the production had provided work for more Chinese actors than any American

film in years. MGM/UA issued an unsigned statement reading: “We believe the claims made

against the film Year of the Dragon are without validity. Regardless of our

opinion, however, we encourage members of the Asian community to view the

film and make their own judgement”. Within a week the coalition represented

fifty organisations and had some demands: “MGM/UA should provide employment

for Asian-American actors in movies that portray Asians with accuracy and

sensitivity. The price of employment in this movie is the perpetration of

destructive and demeaning stereotypes.” Variety reported that, ironically,

the production had provided work for more Chinese actors than any American

film in years.August 24th was designated a national day of protest. The New York Times, the New York Post, CNN, Variety and Entertainment Tonight all reported on the 1,000 protesters in San Francisco and the symbolic coffin that was carried down Hollywood Boulevard and burned in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre where Year of the Dragon was playing. Within three week the Coalition had shut the film down in 36 cinemas, and the initial box office success quickly waned. On August 28th Frank Rothman, CEO and Chairman of MGM/UA, announced that a disclaimer would be added to the nearly 200 prints circulating in New York and Los Angeles. The disclaimer read “This film does not intend to demean or to ignore the many positive features of Asian-Americans. Any similarity between the depiction in this film and any association, organisation, individual or Chinatown that exists in real life is accidental.” Cimino claimed in interviews that his films portrayed Vietnam veterans he had known as a Green Beret, but fact checkers disputed this proving his only experience was six months training at Fort Dix and Fort Sam Houston in 1962, well before US troops were sent to Vietnam en masse. Cynics questioned the release of Final Cut, Steven Bach’s essential book on the making of Heaven’s Gate and the collapse of United Artists, at the same time as Cimino’s new film. Frank Rothman offered to give a portion of the profits from Year of the Dragon to an Asian-American community project or support the development of Asian-American led stories and projects. Michael Woo, the first Asian-American council representative in Los Angeles got a lot of credit for his part in the protests, but some organisations remained dissatisfied with a seemingly glad-handed resolution. Year of the Dragon closed in the US after 5 weeks having recovered only 8 of its $18 million budget. Robert Daly said the film “grossly distorted the public’s perception of Chinese Americans during a time of great misunderstanding and anti-Asian sentiment”. The changes to his novel were significant. Stanley White was called Arthur Powers, Stanley White being the name of a real-life cop Rourke had shadowed during research. Powers wasn’t Polish nor his lover Chinese. The Powers character had no military background. Some of the violence against women does not happen. Year of the Dragon opened in London on 10th January 1986 at the Warner West End and ABCs Shaftesbury Avenue and Fulham Road, one of ten DeLaurentiis pictures picked up by Thorn-EMI-Screen Entertainment just before they were taken over by Cannon whose big box VHS release contributed to its cult status. The Financial Times observed that British critics were raving about it, but most drew attention to Mickey Rourke’s improbably greyed hair, just as they did to his new chin for Harley Davidson and the Marlboro Man 6 years later. Rourke acknowledged that he was “10 or 12 years too young to play a police captain” while Cimino argued that a lot of guys in their early 20s came back from ‘nam grey. Cimino only directed three more movies: Mario Puzo’s The Sicilian, a remake of The Desperate Hours and Sunchaser, which went straight to video in the US. All three were troubled productions, but all three warrant a revisit. Maybe another year. And while 2018 is actually the Year of the Dog in the Chinese zodiac, here at Celluloid Saturday it’s time for Year of the Dragon. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|