The Restoration of "Lawrence of Arabia" |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Columbia Pictures, 1989 | Date: 06.08.2008 |

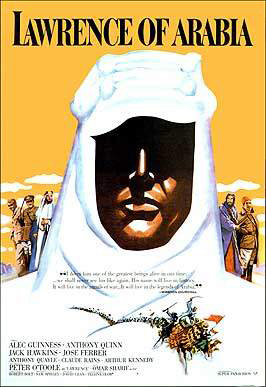

The

original poster from 1962 by Howard Terpning The

original poster from 1962 by Howard TerpningSir David Lean's epic saga, "Lawrence of Arabia," is one of the most honoured films of all time. The 1962 Sam Spiegel/David Lean Production for Columbia Pictures received 10 Oscar nominations and won for Best Picture, Director, Cinematography (color), Art Direction (color), Editing, Music and Sound. In 1986, Robert A. Harris, the archivist-producer involved in the restoration and presentation of Abel Gance's "Napoleon", contacted Columbia Pictures with a proposal to restore the original premiere version of "Lawrence of Arabia" in a pristine 70mm print. Warned that the film might need a bit of restoration, Harris took it as a challenge. Twenty-five years of records indicated that the original negative had never been touched and that full and complete black-and-white 65mm protection materials were available. Columbia gave the "go ahead". What began as a "fun" project turned into a two-year odyssey, encompassing months of exhaustive research, detective work, a touch of modern archaeology, a worldwide search and inventory of surviving materials, the painstaking and meticulous examination of over four tons of picture and sound elements, and finally the total reconstruction and restoration of the film. The project brought together a team of Hollywood professionals including sound consultant Richard Anderson, re-recording mixer Gregg Landaker of the Goldwyn Sound Facility, two dialogue editors, scores of people at Metrocolor Labs, as well as the film's Academy Award-winning editor, Anne V. Coates, and director Sir David Lean. Harris next involved Jim Painten, a friend and partner on other projects, as co-producer of the restoration. The two had met while Harris was working on "Napoleon" and Painten was making the documentary "Napoleon Conquers America". Painten, who has an extensive background in all phases of production and post-production, agreed to help with the technical work in New York and then act as west coast liaison in all areas while the reconstruction was still under way in the east. "When work began", said Harris, "our knowledge was extremely limited". The only thing that was known with certainty was that the film had been released in December of 1962 at a running time of 222 minutes plus additional music. Sometime between then and mid-January, 20 minutes were removed. In late 1970, an additional 15 minutes were cut, reducing the length to 187 minutes. No print of the premiere version was found to have survived. Columbia had no written continuity, no record of any kind of what the 222-minute version even contained. In mid-December, Harris and his New York assistant, Joanne Lawson, visited Columbia's vaults. They were shown through by Columbia's Negative Records Manager, Irwin Rosenfeld. "It was our first look at the cans of the 'Lawrence of Arabia' camera negative," recalls Harris. "We had gone to inspect a few rolls, hoping that they were uncut." They were in for the first of many unpleasant surprises. The delicate 65mm negative was in cans with a rust-like patina. While this was of little concern, some of the cans were almost totally crushed, only being kept in shape by the bulk of the negative inside. |

More

in 70mm reading: "Lawrence of Arabia" cast & credit Restoration of "Spartacus" Restoration of "My Fair Lady" Restoration of "Vertigo" The Reconstruction and Restoration of John Wayne's "The Alamo" Robert A. Harris: Film Restoration on the eve of the Millennium A View from the Trenches in70mm.com News A tribute to Howard Terpning |

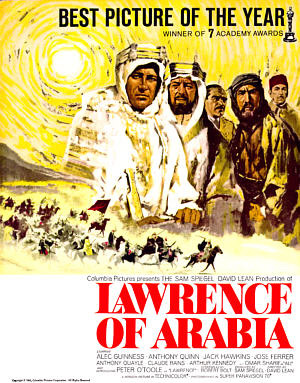

Later

general release poster Later

general release posterIn an inspection room, the cans were opened with the help of tools. Fortunately, only a few feet of leader were damaged. It was determined that the film had been cut for a unique form of printing in which several versions could be produced from the same negative -- footage could be selected to be printed and create dissolves or fades as needed. Unfortunately, this had been done over 200 times, putting incredible wear on the negatives, which were scratched, dried out and warped, and the over 1000 fine splices were falling apart. The negative was shipped to Metrocolor Labs in Culver City. The only magnetic stereo soundtracks in the vaults were taken back to Harris' offices for examination and inventory, which, when measured, ran 202 minutes. They were shipped to the Goldwyn Sound Facility of Warner Hollywood studios. Rosenfeld also supplied used 35mm release prints of the 202-minute version. These would be cut together to form a work copy of the current version without the expense of a new print. Lastly, copies were made of the thousands of pages of paperwork from the "Lawrence" files. Harris ordered tons of material to be shipped in from England, Germany and Holland. Painten came east to help review paperwork and plan the months of work ahead. The reconstruction phase of the project had begun. In early January, the shipments Rosenfeld had promised began to arrive: hundreds of thousands of feet of unlabeled and unmarked 65mm negative trims and unused takes, hundreds of boxes of 35mm trims and unused takes, and hundreds of thousands of feet of unmarked picture and magnetic film. This was followed by two surviving 70mm prints -- one in German, one in English with Dutch subtitles. Both turned out to be the 202-minute version. Every element had to be inspected, identified, catalogued and sorted. A second copy of the magnetic track arrived, again the 202-minute version. It was marked as a protection dub, a copy, but it contained splices where some of the lost footage must have been deleted. When it was played, the magnetic oxide flaked off, leaving a film of rust everywhere. It clotted the playback heads and would run for no more than 10 seconds at a time. Marked as a copy, this turned out to be the original recording. Shipped to Goldwyn, it was inspected: The original track to the 202-minute version wouldn't run. Before the reconstruction could continue, the negative had to be printed. The lab patched it wherever possible and finally ran the negative to produce a first 70mm work print. Although the color was quite yellow, the fragile Eastmancolor dyes had not faded over the years but merely shifted. The color would be correctable. Even the heavy scratches, when printed with a liquid coating to fill them in, seemed less in evidence. The test print was shipped east. |

|

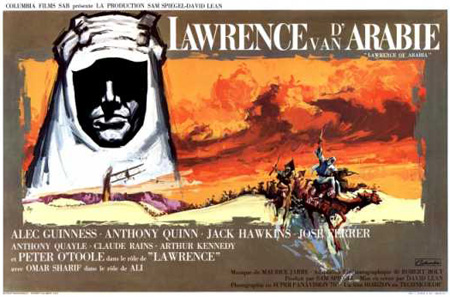

Small

poster from Belgium Small

poster from BelgiumFrom the print, several things were determined. First, because of a selective process used in the early '60s, fades and dissolves could be eliminated or moved without problem. In areas where Harris thought that cuts might be rejoined and where dissolves had been inserted for the 202-minute version, several feet of normally unseen footage remained. However, when compared to the two existing versions it became clear that the negative had been cut not once, but twice. Only the 187-minute re-issue version could be produced from it to exact specifications; when the film was re-cut in late 1970, even parts of the 202-minute version had been removed. "We felt that we still had the protection masters," recalled Harris. Color film is protected archivally by the production of three black-and-white (silver) masters. Each master (cyan, magenta and yellow) carries a portion of the spectrum. When the three are reprinted on color negative film, a duplicate negative of fine quality can be produced. "Then", continued Harris, "came the report from Metro. They had examined the masters and someone had cut them. They held no more footage than the camera negative. No one could understand why anyone would cut up the negative, no less the protection material." Meanwhile, work progressed on cataloguing the various elements. Every can of 65mm negative was opened, and all scene and take numbers were compiled, listed and interrelated by can number. Painten had returned to L.A. and then in January was back in New York. The attempted identification of the various unmarked 35mm elements had begun. Among the thousands of pieces of film were short strips of black-and-white dupe with an optical soundtrack. Harris unrolled a few. They didn't look familiar. The quality was awful. Late that night, the two were attempting to make some sense of the tons of material. It was almost midnight and Harris had an idea. Returning to the office, he took a black-and-white dupe, threaded it on the editing machine and the two had their first look at bits of the missing scenes, with sound. Into the morning, the two began to cut bits of old film into the "new" print produced in the early '80s. The scratchy black-and-white dupe was cut into newer color footage in which the sand was blue. Martin Scorsese filled in as director, answering a myriad of questions as to what shots might fit together. Painten had to return to Los Angeles, having been given the position of ABC production executive for “Moonlighting”. He would continue to help from L.A. in whatever free time he could find. At this time, Harris made contact with the woman who held the key to the success of the project. David Lean was away, scouting locations for his next production, “Nostromo”. Editor Anne V. Coates was the only other person who could shed light on putting the pieces of the puzzle back together. After attempting to find her in England, Harris discussed the problem with a friend, producer Jon Davison. Ironically, Coates was cutting a film in the office next to Davison. As Painten commented, Anne Coates is the one person who knew not only how the picture was put together, but also how it had been taken apart." Coates was thrilled to hear of the restoration, offered total assistance, and supplied a basic rundown of the original cut of the film. As Lawrence's goggles were the first piece of film to be edited out, she advised them to "keep looking for the goggles". |

|

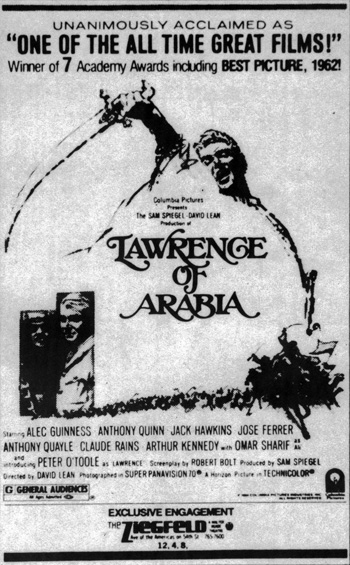

Re-release

in 1983 in New York Re-release

in 1983 in New YorkShe also contacted Lean in Spain, who was excited by the restoration. Lean asked Harris to call him, and they made contact when Lean was in Los Angeles. Lean would not only add his support to the project, but would be in Harris' office the following Tuesday on his way through New York. He wanted to see the materials. Harris had cobbled together a first indication of the basic shape and content of the finished film. Finally, they were looking for definite materials. Dubbing sheets had been found which gave an indication of the footages at which changes had occurred. These were "slugged" with black film, while the black-and-white dupe footage interrupted the blue sand of the new prints. The director gave his thoughts as to what was yet to be added. Offering his help, Lean asked the inevitable question, "What do you intend to do if you can put the picture together, but you can't find the tracks?" Harris answered that he would use tracks that survived from alternate takes and, failing that, record new dialogue. Responded Lean, "If that's what you need, let me know. Alec, Peter, anyone else you need will be pleased to help". The reconstruction continued. Before any of the original negative could be cut back into the film, it had to be found. Nowhere in the hundreds of cans was anything marked "Deletions: January 1963- Reel l." The picture elements had to be located, measured and prepared before they would know what tracks would be needed. Months before, the 202-minute version was compared to the script. Additions were noted. The next step if the reconstruction was to be completed was to use alternate takes and trims in place of the original missing camera negative. The can that contained the trims of the goggles was located. At the head of the shot was the scene number followed by footage of Lawrence's goggles swinging from a branch. This one was easy. No dialogue. He continued in another can, pulling the next missing material, that of a pull-back, a tracking shot beginning with a close-up of a bronze bust of Lawrence, moving back to a medium shot in which a legend beneath the bust could be read. The slate was pulled with the start of the camera movement, and then it ended...too soon to work. The tail of the shot was too wide an angle and too short. "Possibly, if we slowed it down and reprinted frames," Harris thought. He continued winding slowly through the roll of trims, and then, quite suddenly, he came upon another shot of the goggles. This was followed by a splice in the negative, cutting to a shot of the bust of Lawrence again. Harris was in near shock. In his hands was finally the long-missing camera negative, the actual pieces of film that had been used to produce only a few prints in late 1962. Found at last, they had been returned to the hundreds of cans of trims, as if they had never been in the film in the first place. In the next few weeks, all of the missing negative was located except for one shot, which was replaced by an alternate. The final piece of negative to be located was a unique Columbia logo. Since there had been no 65mm logo available, a new painting was produced in England. Photographed on the Super Panavision 70mm film, it was used for only the first few prints, then replaced with a more generic version blown up from 35mm. It had been the first cut to be made, and now, 25 years later, was the final piece to the "Lawrence" puzzle. The restoration was about to begin. Late in 1987, Dawn Steel was appointed the new President of Columbia Pictures. The importance of the restoration of "Lawrence of Arabia", was stressed to her by Scorsese and another Lean fan, Steven Spielberg. Steel was anxious to continue the vital preservation of one of Columbia's most prestigious films, supporting the most extensive, complex and expensive restoration of a film ever attempted. |

|

Restored

version shown in Australia Restored

version shown in AustraliaWithin weeks, in March of 1988, the restoration was headquartered at Warner Hollywood, where all of the sound would be produced at the Goldwyn Sound Facility. Rooms were packed from floor to ceiling with tons of "Lawrence of Arabia" material. Harris had 65mm protection material produced on all of the cut scenes. No chance would be taken that they might now be destroyed while running through a printer. A 35mm internegative was produced from the new scenes by Deluxe Labs and a print produced. This was then inserted into the 35mm work print. The 70mm material was inserted into the 70mm work print. Because of the unique film format, two work prints had to be constantly compared and upgraded as the work progressed. Only the 70mm print had numbers printed along the edge, which were needed for negative cutting. Only the 35mm print could be run on an editing table as the soundtracks were built. Although some sound had been taken from the black-and-white dupe footage and some culled from alternate takes and carefully honed to fit the picture, finally over eight minutes of film had no sound whatsoever. There were no effects, music or dialogue. Effects tracks were created by Academy Award-winning sound editor Richard Anderson, borrowing effects from elsewhere in the film. Foley tracks, those sounds that people make as they move and breathe, were created by Harris and dialogue editor Jim Christopher after hours at Goldwyn. The other major contributor was re-recording mixer Gregg Landaker. It was his responsibility to take the various tracks prepared by Anderson and create the final 6-track recording. It was Landaker who had to create stereo where there was none, to make hissy, old optical tracks sound better than they ever had, and also to clean up problems inherent in the original 25-year-old recordings with newer techniques, problems that could not be heard originally were now obvious. Further, because of the various re-cuts, dialogue was now out of sync, even on the master tracks. Dialogue editor Burt Weinstein would arrive at the cutting room after finishing his day job, ready to do whatever was necessary. In mid-April, the new dialogue was needed. The missing dialogue was revealed when Harris had his Los Angeles assistant, Jude Schneider, locate a hearing-impaired couple who could lip-read. Three scenes were finally scripted in this manner. It was time to record the needed lines. Peter O'Toole and Sir Alec Guinness made themselves available in London, where they were directed by Lean. Anthony Quinn re-recorded his two lines in New York one afternoon before leaving for Europe. Arthur Kennedy, who was located in Georgia, met Painten at a TV studio in Savannah. After viewing a videotape of the needed footage, Kennedy's missing dialogue was recorded by Painten on a Nagra lent by Goldwyn. Even the new recordings had to be mechanically altered to compensate for the actors' voices having matured over the past 25 years. By the end of April, the restoration was in good shape; the material was looking and sounding extraordinary. It was time for David Lean to approve the final work and make any changes. As soon as Lean arrived in town, he was anxious to join the restoration team. They worked tirelessly far into the night. |

|

2003

re-release of the restored version in Los Angeles 2003

re-release of the restored version in Los AngelesLean sat at the editing table, seeing for the first time in 25 years a facsimile of his original vision. While viewing the print, Lean and Coates noticed that the second reel was reversed and commented that the camels were going right to left, which couldn't be correct. He always had the camels going from left to right. After checking the other prints of the film, the team discovered that the error had occurred during the production of a 35mm scope interpositive in 1966 - which was made directly from the original negative. Therefore, every theatrical, video or television print since 1966 (with the exception of the 1971 187-minute reissue) had 10 minutes reversed. It became apparent to Harris and Painten that Lean was concerned that the film would still work, that the restored scenes not inhibit the flow of the story. Lean began to wonder if some of the added scenes might not be unnecessary, and that some new cutting might not be a bad idea. "David was exceedingly patient with me as we began to partially dismantle the restoration," recalls Harris. The completed 70mm work print with the new 6-track Dolby Spectral Recording was screened for Dawn Steel and the staff of Columbia Pictures at the Academy of Motion picture Arts and Sciences. The film had not only been restored, but had been re-cut to Lean's specifications. After 26 years, the director had finally gotten the "fine cut" of his masterpiece. Steel gave approval to clear up a few scratches and other marks that had been plaguing the negative, and the production of preservation and duplicating materials began. Lean gave his final approval and moved on to Cannes, where the festival was held in his honor. Metrocolor began the tedious job of creating, for the first time, a 65mm duplicating interpositive (IP) on "Lawrence of Arabia," Everyone involved knew the printing life of the negative was at an end. Steel gave permission for a second IP as additional protection should the camera negative fail. In May, as the final runs of the negative were needed to complete the project, hundreds of old splices began to open. The negative began to tear while in printing. A final, fully color-corrected print could not be produced. The chance of it tearing before even the first IP was created became a reality. As carefully as Metrocolor would try to handle the negative, it continued to tear, losing shot after shot of original material. The process was halted. Negative cutters began to place tiny bits af mylar tape on the edges of every splice that looked endangered. Hundreds of repairs were made. Some reels of IP were completed since the entire negative had to be re-cut into what are called "A" and "B" rolls so that dissolves and fades could be put back into the film, each IP took two runs of negative. Some rolls were simply not making it. Harris went to the black-and-white protection masters to produce new dupe negative. Sometimes this worked, sometimes it didn't. Differential shrinkage had caused the masters ("seps") to misregister. Cyan and magenta ghosts of elements of the picture would appear beside the actual content. Harris went back to the lists of shots of available takes, replacing or extending what remained with trims of the original shots. Finally, the first IP was created. One problem caused by the slight color shift from the original camera negative was the loss of the bright blue skies normally attributed to the film by those who had seen original Technicolor dye transfer prints from 1963. The prints taken from the original negative lacked the brilliant blue. Finally luck was with them. The new Eastman duplicating interpositive and internegative seemed to pull every bit of available blue out of the original negative; the final result looked right. This, combined with the exceptional quality of the new lowfade Eastman release print stocks, made the film look better than it did when it was new over 25 years ago. When Harris and Painten embarked on the project, they decided that if a certain quality could not be attained, they would not attempt to complete the restoration. "It's a David Lean film," said Harris. "At no time were we willing to drop below his standards. You give it your best, nothing less. Everyone involved did." Columbia pictures presents the Sam Spiegel and David Lean Production of "Lawrence of Arabia," starring Peter O'Toole, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn, Jack Hawkins, Jose Ferrer, Anthony Quayle, Claude Rains, Arthur Kennedy and Omar Sharif. The film was directed by David Lean from a screenplay by Robert Bolt and produced by Sam Spiegel. "Lawrence of Arabia," was reconstructed and restored by Robert A. Harris. The restoration was produced by Robert A. Harris and Jim Painten. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|