“All Art aspires to the condition of Music” |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Mark Lyndon. Sunday 3 September 2011. Retyped from audio files by Margaret Weedon | Date: 28.10.2011 |

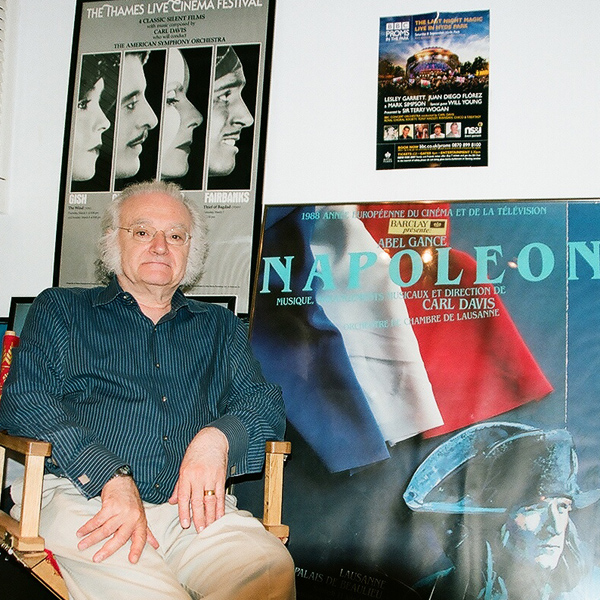

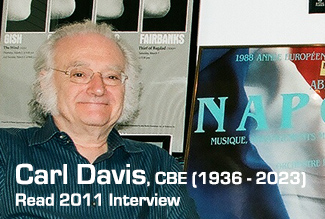

Carl

Davis in his study. Image by Mark Lyndon Carl

Davis in his study. Image by Mark LyndonML: The star witness to this paradigm must surely be Carl Davis, the creator of the greatest film score of them all – the score for Abel Gance’s classic film "Napoleon": and yet, as Kevin Brownlow admits in his book “Napoleon”, he “harboured serious qualms about the big show”. How could you keep in perfect synchronization with the picture for five hours? CD: First of all we did it in four chunks; it was five hours long, at that point, - the longest part was the first part which did go to nearly two hours - that was the challenge, although I really did not equate that aspect of it in my mind so as to articulate it. It was really like writing a big ballet or a big opera; the function was going to be the same; it was going to be continuous except where you might want a dramatic silence – that is then written into the score. I gave myself safety nets so that if I got a little behind or a little ahead I could wait, or I could catch up a bit every once in a while, but when you get to very long sequences, for instance the end of the whole first part where the storm alternates between the storm at sea and the storm in the national assembly – intercut - it was quite long, 11 minutes without stopping, so I had to learn how to do that. My conducting experience ..... Up to that point it had been in a recording studio and there you have all the help in the world; you have click tracks, you have wipes, you can do it again! Now, for the first time, I was in a live situation which means there may be errors but we have to go for the performance, and not get stuck anywhere. So it was to me a mystery as to how I was going to do it; it was the first one we had attempted and, in a way, I suppose the experience of having spent twenty years working in a studio did help me - at least in terms that I was used to synchronising music to film. That is the name of the game – what is film music? - it is music that fits the film; that is one definition of it anyway. I had to work out for myself; there is no school you can go to at this point which will teach you how to deal with a silent film in the way that those guys did it in the 1920s. We know what it is like to improvise – I did some of that. In fact while we were preparing the Hollywood series, there was quite a long lead up time and whilst you are not going to use me for many months, - to the point when anything was edited and ready to be produced; and to keep us in the swim, I proposed that every Tuesday afternoon we would screen a film - interesting films of all kinds, some of which may be included in the series, but perhaps not, and by doing that I got into it a little more – playing for “Intolerance” or “Thief of Bagdad” – or the big ones including one I am dying to do which starred Beatrice Lily - wonderful comedy – I think it is called “Exit Smiling”, absolutely charming. What emerged was something like a ballet or an opera score, but instead of the singers and dancers there was going to be the image which I had to follow; if you are working in ballet or opera of course people are responsive, they are listening to the music, or you are listening to them, and there is some flexibility. Here of course there is none at all – the film is implacable – it goes on and you have got to be there in a relationship to it, and the first thing to realise is that it all depends on tempi. If I am able to fulfil my plan in that I might have conceived a piece to go in a certain tempo, and that tempo would match the action; I would know that this is going to happen on this bar, Napoleon is going to stand here, he is going to walk across the room, he is going to open the door – whatever is going to happen it happens at a place in the music. Once that plan is there, and written onto the score, the instruction to me is to “be at best bar by this point”, then everything starts following, and when it is really, really working, I am hitting these points, and if I am a little behind or a little ahead of it, I can make the adjustment, but the film has to be right; the film is the boss, I am locked to the film, and when in fact it does go together, and the plan is fulfilled, I am very, very happy; it is very satisfying. ML: And the audience rise to their feet – CD: There is a kind of chemistry that takes place in which we are forgetting there is an orchestra, and the music helps you forget that there is a dialogue, which is interrupted with what they are saying, but the music is actually not going to be interrupted; I’m not waiting for a card, I am actually sustaining the mood across the bar, across the card, so that we go through, and the audience is still in the right frame of mind whatever it is - dramatic, comic, and so on. |

More in 70mm reading: Kevin Brownlow Interview Projecting “Napoleon” – une pièce de resistance Abel Gance’s "Napoleon" Presented in “Polyvision” “Napoleon”: The North American 70mm Engagements We saw NAPOLEON on Sunday in Amsterdam "Napoleon" in Triptych was an Absolute Triumph “Napoleon" in San Francisco |

The greatest works of music ..... | |

Carl

Davis' latest CD, released October 2011 Carl

Davis' latest CD, released October 2011ML: The hallmark of the greatest works of music is the perception, before the event, that they are in fact unplayable; and Beethoven’s Third Symphony, “The Eroica”, is a classic example. It was also the foundation stone at the core of your score – this is what you built it on and you had thoroughly researched - there was a good match in Beethoven and Napoleon, and what was crucial really was the thoroughness of your research into the symphony itself; the piano variations, and its first appearance in the ballet Prometheus. All these found their way into the score. And you were developing from that. You also said you took great pride in looking for compositions by other composers working in France at the time of Napoleon: Gluck, Cherubini, Mehul, Monsigny, Gretry, Dittersdorf, Gossec. Napoleon was known to have said that he could listen to an aria from Paisello’s opera Nina, every day of his life – the melody accompanies the picnic scene in Corsica. You also looked at the first printed settings of the songs of the French Revolution and preserved these in their original forms; I think this was crucial to creating a truly authentic feel – as if you were there – the Cinerama effect if you will. How hard was the research – how hard was it to get hold of these materials? CD: The research was a delight; there are libraries that I had inhabited for decades before this arose; doing the thirteen hour project of Hollywood had really prepared me and, the more I think about it, it prepared me very well for this procedure. The first thing was to get a theoretical foundation of what was the score going to do; what followed "Napoleon"; what was set up by "Napoleon" was that our life was going to be somewhat different - in other words, we were not in a commercial cinema, there was not a set orchestra; we were going to examine "Napoleon", and the subsequent films that I did, as unique, and so they could have their own sounds and their own musical life; it is not a staff orchestra and that’s it. |

|

The timing of the first or single performance | |

|

First of all, I had a very big practical

problem; the decision to actually do this single performance, which was

going to be November 30, 1980, was not made until mid-August 1980; so I had

about three and a half months to do the version, which was just under five

hours, so immediately it was quite clear to me that there was no way I was

going to be able to write a completely original score. At this point, with

my knowledge of how they did it in the course of making of the Hollywood

series, I got a chance to talk to the last cinema organist of the Paramount

Theatre in New York, someone who was still practising. We are talking now of

the mid 1970s so you could still find a few 70 and 80 year-olds around. I

got first hand information on how you would assemble a score of this

enormous length in terms of the epics they had played for – the Cecil B.

deMille films, and so on; basically they worked from a library; they had

accumulated in their life time a huge amount of already composed music and,

as they were not composers themselves, would find pieces that they thought

appropriate to the film and stick them together. With this experience behind

me, in the Hollywood series I had alternated between pieces I composed and

pieces by other composers that I thought were appropriate, I used perhaps a

little bit of irony between the pieces I chose and the image, and so on. |

|

The big three – Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart | |

|

I was already blooded with the fact that we

were going to find other music that is appropriate, but I thought that it

has still got to be homogenous in a way – it cannot just suddenly be a bit

of Wagner, then a bit of something else, and suddenly it becomes a real grab

bag; if I was going to borrow what was going to be the theme? This is the

life of Napoleon from childhood to a particular period – 1797 - when he

really came into focus as a General following his first major act of

liberation of Italy. What if I were to offer the public a parallel history

of the musical life of Napoleon’s own time? Who was alive, who was working,

who did he know, and who was affected in their lives by Napoleon? This is a

formidable list – the big three of Beethoven, Haydn and Mozart were all

contemporary of him - and certainly stylistically within that frame. I

decided I would not go to sources that were much beyond the life of Napoleon

– although he lived into the 1820s, but make about 1815 my target, which

basically gave me late 18th Century music as the principal source. Then came

the “problem” of Beethoven; in all conscience, can I be pilfering from these

marvellous pieces - great, great pieces of music – as film music? Is this

not too outrageous? It was a dilemma; it was a real crisis of conscience;

what am I despoiling here, if I am at all? |

|

Beethoven and Napoleon | |

Carl

Davis in his study with interviewer Mark Lyndon. Image by Mark Lyndon Carl

Davis in his study with interviewer Mark Lyndon. Image by Mark LyndonI read a bit more about Beethoven’s views on Napoleon, and the story of the Eroica Symphony which initially was dedicated to Napoleon, then when Napoleon declared himself Emperor - in other words, what was a liberator became a dictator - Beethoven disfigured the score; he made a mammoth scratch across the front page and changed the title so that, instead of being dedicated to Napoleon, it was the Erioca Symphony. He had a view on Napoleon – sometimes good and sometimes bad; there is a very late letter or note, dating from the 1820s, which said “I never really got that bastard – I never really knew which way to take him”. Another book that was a great influence on me was by a Dutch writer called Huizinga, who wrote the “The Waning of the Middle Ages”. He also wrote a book called – “Napoleon for and Against” - and he said that every decade or every two decades there is a shift in France in the public view of him; if the country is well and prosperous, and things are fine politically or economically, Napoleon is seen as a really nasty thing, really bad; but if France is threatened – well - ML: – “La Patrie en danger !” CD: Yes - suddenly the Napoleonic spirit becomes important so that De Gaulle during World War II was seen as an admirer of Napoleon, and it just kept shifting - and the fortunes of the film, and the view of the film, kept changing as well. Gance never stopped working on it – reissuing it, adding sound, doing sequels, etc.. ML: It is really a “Forth Bridge” of a film – it has never been finished. CD: No, no, it has never been finished; the cut we learned from Kevin, it was the first time we actually knew that he had based the American version on the cut that Gance had done, prepared for its premier, where he also could not show it to full length. Going back to the music, I think it is an interesting story of pro and con Napoleon, and it is more ambiguous, has more light and shade, rather than a straight forward pinch; it really is someone who is responding to the Napoleon alive and active, and doing things, even though there is a point where Beethoven was living in a suburb of Vienna, cowering under a table because Napoleon’s cannons were bombarding Vienna. I thought that if I made the Erioca the centre of the piece and that was going to be the spirit of Napoleon, there was another factor in it which actually had to do with the character of Beethoven’s music; I researched Beethoven’s jobs. ML: “The Coriolan overture” was very powerful for me. CD: – Yes it would be quite interesting to see how he made a living. He had a ballet commission, he wrote overtures to plays, he wrote incidental music for plays like “Egmont”; he wrote minuets for dancing, as they all did, Haydn and Mozart as well. ML: They had to be jobbing composers: CD: It was interesting to look at the jobs to see how it could work. |

|

Authentic to the period | |

|

CD: There is another thing about the character

of his music, and this actually works for Haydn and Mozart as well, in the

course of a movement of a symphony, or even the simplest dances, it is full

of dynamics, accents and contrasts, and this works well with the cutting: as

I’m conducting, if I can actually find the pulse of the scene and do it you

have all sorts of stabs, fortes and pianos, events in the music, and they

seem to coincide beautifully to the way the film is cut; I thought there is

going to be an added advantage, a theory of mine, we are looking at

re-creations of rooms, costumes, wigs, props in an attempt to be authentic

in period. Having the bulk of the music be derived from basically late 18th

century music, it will go well together, and the dynamism of a Beethoven or

the symphonies of Haydn and Mozart as well, it really does coincide with the

mood – adds to the authenticity of it, and also has a big dynamic drive. The

personality of Beethoven was very strong very dramatic, not so different

from Napoleon himself who was a very active, very decisive person. That

confirmed for me that this would be all right; and it would be convenient in

one sense, but there were three areas to the score where this did not quite

work: |

|

Corsican folk melodies | |

|

Area 1 - About 40 minutes of the first part of

the film is spent in Corsica with the family; then the political intrigue

about which country should he align himself to, and so on; I thought we

could do with some authentic Corsican melodies, and that was an area of

research to find folk melodies that might lend themselves to the period. But

this had then to be composed; you are starting from scratch, from a single

little tune, and you have got to build this up to the reunion with the

mother, and the sisters and brothers. All the things being chased by the

opposing forces up and down the Corsican coast; jocular scenes with his

little nephews and nieces; anything domestic in this part of it – but then

that gave me a leitmotif; it gave me a theme, one of them in particular,

which is a slow lament, gave me a theme which could be used throughout the

film. ML: A Motif? CD: A motif exactly, so that was one area, |

|

The Revolution | |

|

CD: From about half an hour into the film you

have the story of the Revolution, the early part of which Napoleon is an

observer and does not have a role – he simply watches it. He is already

suspected by the Reign of Terror, and might have ended up on the Guillotine.

So that then takes in the creation of the Marseillaise, and teaching the

Marseillaise, but I knew more, there were many more, that I could quote that

were appropriate. ML: You had a Chant du Depart, a Carmagnole, you had Ah Ca Ira! (CD: Yes, very good!) ML: But I am a great fan of Bernard Hermann and his music, but his shower scene – that stabbing music – (it has lost its power to send a chill up and down my spine) – however, your Hurdy Gurdy music – Robbespiere – it is still a haunting sound. CD: Yes, it is a haunting sound, isn’t it? - Rrang! Rrang! Rrang! - It is a special thing on the attachment that makes a buzz. ML: It’s that special buzzing sound that makes it magical; it still has the power to chill. CD: I hope I can still find one in California – it is a dilemma. |

|

18th Century dances arranged for Hurdy Gurdy | |

|

CD: I had a meeting with the first player of

that; she came to me with a score, with a music book which had 18th Century

dances arranged for Hurdy Gurdy as they were published in the mid 18th

Century. I grabbed about four of those tunes immediately because they were

absolutely suited to the instrument, and they were from the time. ML: Again the sense of authenticity, time and time and time again; the extent to which this was a labour of love, but Kevin also quotes you again saying that you also decided that – “When I found the view of the director became subjective and not strictly historical, that would be the moment I would compose original themes.” CD: Yes, that was the third area. |

|

The Story of the Eagle | |

|

ML: The most important was to describe the

Eagle of Destiny, which was a variation on the Erioca or the Marseillaise? CD: Well it has a couple of intervals, but I did not think about that; I had already been playing with the Erioca theme, but I thought they had to be the Gance point of view from the 1920s; from that vantage point in which he admires the dynamic, and the life force and, at any time of crisis, he superimposes this image of the eagle. The story of the eagle goes back to when it was given to him by an uncle and he kept it in the garret of the school; some nasty colleagues, little boys, released it, and then it came back to him. All this is fairy tale but then throughout the film right to the very end, where you suddenly get the eagle’s wings across three screens, you know that he is celebrating the will and power and charisma of this man and his drive; and this is a symbol that is used by dictatorships and democracies; the independent spirit of the eagle seems to cover a wide variety. So I composed a variant on the Erioca motif – actually it is just the first two notes that are the same as the Eroica - and then I go my romantic way with it. ML: That is the best Cinerama music. CD: Yes, yes, the first time you hear it is on a solo horn and that fades to a scene of the boy Napoleon with his eagle, feeding him, giving him water. ML: You are probably our best ballet composer now, and your affinity comes out in the Bal des Victimes – the gigue, the fan, the tambourin. And the whole audience in a sense is dancing with you, and the images on the screen, and this is just before the interval and that is really important. CD: That is a wonderful scene - again in research I found that is where the Monsigny and the Gretry, and the Gossec give them what they might have danced to. Returning to Beethoven, I was thinking of the use of the finale of the 7th Symphony when he is really greeted in triumph; going to Paris in jubilation; you see people dancing in the streets, although that would have been to folk melody or ca ira, or something like that. Using Beethoven indicates him as the catalyst in making this happen – that Beethoven and Napoleon come together when he is making something happen. ML: Both men of action – it is all about action – making history; changing the world forever. CD: For Beethoven it was in his head as he could not hear it past a certain point. ML: He wrote the score to that period as we look back on it; he really was the bard to the whole revolutionary period. CD: Yes he did change it; it was interesting because I thought it would be good not to use Beethoven for the sequence, but to find the most Beethoven-ish music in Haydn and Mozart. He knew both of them, in fact when he was young he did show lot of his compositions to Haydn, sometimes you can find it, especially if you look for minor keys in Haydn and in Mozart they sound rather Beethoven-ish; they are very strong and had that sort of accent, and hard rhythm; you can find the sounds, and of course they are of the same period. ML: We are going from minuet to something more radical: you had another scene that haunts me to this day – where again it sends a shiver down the spine – but not of terror this time. |

|

The ghosts of the convention scene | |

CD: There was one piece of Beethoven which is

a set of Piano Variations which is called Variations in C minor, which I

have always loved. A piece I studied when I was a kid. They are short

Variations and half of them are in minor keys. CD: There was one piece of Beethoven which is

a set of Piano Variations which is called Variations in C minor, which I

have always loved. A piece I studied when I was a kid. They are short

Variations and half of them are in minor keys.I thought in the scene in the first bit of the film, which is Napoleon as a witness to the Revolution, he is viewing the Revolution from his garret, his room and sees all these unspeakable acts; we have Danton at his forge, and so on. Because these short episodes would go with the short Variations; they were very, very dramatic. But then I thought I would love to use this for when the ghosts come back because of the sinister nature of it - the stern nature - but there was nothing ghostly or lurid about the Variations. Thus, I called upon one of my team of orchestrators, several of whom were composers in their own right; Colin Matthews was handling that section for me. I said – “I want to you to pretend that you are Anton Webern or Schoenberg - it is ghostly and, if you take my C minor theme, and exercise your ability as a composer to give me this atmosphere but using the theme ..... don’t just give me - Bom bar bom bom ...”. They were doing all sorts of stuff – they were giving me the full vocabulary of contemporary music – there were all sorts of marvellous slides, it is very very complex and the brass going .... braaaagg ... and with funny mutes, not 18th Century at all; I asked him to give me horror music, and he did, and that was very, very successful; I had given him the concept and he then did it. |

|

Violine and her shrine to Napoleon | |

|

ML: Another scene that Gance himself said he

did not like and they cut it out in the shortened version - it was Violine

and her shrine to Napoleon. You managed to touch the heart but without any

sentimentality, it was an enormous achievement. When Josephine walks in and

Violine is distressed beyond measure that her god is actually gone, and

there is the shrine to him, a little statuette, that she was worshiping, as

would a bride. It was so touching. CD: There is a scene that was actually derived from a very late piano piece – a bagatelle - which I seized on. I tried to view her from what I knew; she is a fictional character, and so why did Gance introduce her into this? I think he was making her represent the people of France who followed him blindly. The scene where she has saved all the bits and pieces, a feather, etc., are like the deception of the people of France, because ultimately he became an Empire in which he planted members of his family. ML: The retreat from Moscow. CD: Blends into Hitler – ML: “Able was I ere I saw Elba”;.. feet of clay. CD: I thought it was about the seduction of the people of France who trusted him and I thought she needed this faith in him, worshipping him, and so that as well as using this Bagatelle which is gorgeous, orchestrated - ( it is just a piano piece) - then in the last scene when she and Josephine pray to his image - I bring back the eagle theme - played on the flute – very very gently, so that they are both in love with him – I saw it as France. (ML: The whole Nation enthralled - CD: That aspect of it – blind adoration ) |

|

La Havre | |

|

ML: Finally, your memories of actual

performances - the most memorable performances - Kevin cited the one in Le

Havre, in front a French audience, it is their history and you got to them -

a few surprises here and there? CD: It was a little muted – it was a gigantic theatre and we were at the bottom of a very deep pit, making it a quiet performance! I do not know how effective it was - or if everyone could hear the music, but the main thing was that for the first time France saw Kevin’s print. The orchestra who played the music for it, called the Wren Orchestra of London, does not exist anymore, but they did a large number of performances. By 1983 they already had done it maybe ten or twelve times; we had many people who had played virtually all the shows. It was a very confident performance musically. There were train loads of people coming up from Paris interested in film to go and see it; it was a great coup of this man who had just opened the Arts Centre to have snatched it from Paris. The whole question of showing it in Paris was very controversial, and there already was the rivalry of the two productions. It was highly significant and it was all over the national press – “un symphonie d’images – une opera sans voix”– very nice. Huge spreads, and stills, and so on – it was very exciting and that paved the way the following Spring of doing three performances in Paris; it was the beginning of its overseas career for me. It went very well and that was highly significant. The story I like to tell – the different views of "Napoleon" - is that there is a scene in the second half – the Battle of Toulon - where Napoleon is commanding the army; he is a Captain at that point, and because the English Navy have appeared in a different place, and he has found himself with the cannons in the wrong position, he says (in the English version) “Turn the cannons” and it comes back ”Impossible, my Captain”; they said “Impossible is not French”. In England this is greeted with great derision, and everyone has a hearty laugh. In France, I was waiting for this moment, what would happen? – a standing ovation – they clapped and cheered!! ML: Do you think there is any chance of a performance in the Opera House – Garnier – one day – un jour? CD: I think they have attempted it – but not with my score: ML: The one and only! CD: Well you never know what is going to happen with that. |

|

British Film Institute | |

|

CD: The discussion about rights ended in a

decision that the Images and Coppola did indeed have the rights. The last

performance that you saw in 2004 was the last time I did it, and I thought

that could be the finish of it. We were all very depressed, thinking it all

started on the wrong foot. If we go back to the origin of it, everyone who

had operated in 1980 thought that it was going to be possible. David Gill,

Kevin and I thought that the British Film Institute had the rights.

Basically funding turned up to do a single performance and, as far as I

knew, there was a document sitting in a drawer of Anthony Smith, the then

head of the BFI. Otherwise why would we be doing it if we had thought at the

time, honestly, that we did not have the rights: it was a great dilemma.

Kevin had been working on the American version, and so it was not that it

was a secret, or that we did not know; we had to say that we did know. Thames TV was very enthusiastic, following the Hollywood series, which had been repeating, and they were able to sell it around the world. The series was very good in translation because much of the material was just film and music. So it was a very nice programme to put titles on, James Mason could be re-voiced; the rest could be title cards – it was a very workable. ML: Was it Lelouch - from reading the book (dare I say this?) the villain of the piece seems to be Claude Lelouch who was playing strange games, and the terrible irony that at Gance’s funeral, Kevin found himself standing next to Lelouch who had bedevilled the thing throughout - according to his version. CD: To my understanding, if you were actually made an offer, and there was no counter offer - an isolated performance for the BFI – (which is dedicated to film preservation) - a situation where there would be hundreds of performances and big tours around the world, and maybe set in musical, it is not too much of a decision to make! My dilemma, and this is all about the story of the tale of two scores (like the tale of two cities!), was that when it came up to do this one, and we knew that there was the American one; the first thing said was - “Did we have the rights to do it?” Yes we did, we thought, so it was not a question of being deliberately criminal, because it was 1980 and the discussion about these rights began only quite recently: it could be the thirty odd year span. ML: It is a long odyssey – CD: and we are still here! - I did say OK it is very very exciting and we know historically what happened. I thought we will never have another chance to do this – (Kevin slightly misunderstands about meeting Coppola - he got it wrong and I mean to correct that). |

|

Meeting with Francis Ford Coppola | |

|

CD: You recall in 1981, “Apocalypse Now” was

up for a BAFTA award and Francis Ford could not come to England for it; the

music was also up for a BAFTA award, and his father, Carmine, came. Kevin

wanted to interview him (this was in March 1981 BAFTA time – they were

staying at the Savoy). He asked me if I would go with him to the Savoy in

case Coppola asked him something about music that he would not know what to

say. I did not really want to because I knew he was doing the "Napoleon", and

it annoyed me; but anyway, he twisted my arm and I went along. Carmine was

rather suspicious of me and I said I had worked with Kevin on the Hollywood

series. So I met him but I do not remember much of the particulars; there

was one comic question – which was a very Kevin thing – he asked did he give

Francis the middle name of Ford because of John Ford (there was a brother of

John Ford) was it any relation, and he said “No, No! I was in Detroit, and

we had to play the Ford Hour”, which was a television programme of the time,

and they obviously did some concerts; he was with the Detroit Symphony at

that time. So it was after the Ford Hour! (dutifully noted by Kevin in

miniature notebook). CD: That was in March and our series was out: then came the moment in June where we had to ask should we not do the whole film? What about "Napoleon"? The money? It seemed a definite possibility: we all sat at the BFI; there was a man from the reels and we all looked at it on a Steenbeck Editing Table, in the old fashioned way. Since this was going to be a monumental task, and really a huge commitment for me, which may end up being one performance, I wanted some very strong justification for doing it in the face of knowing that the Americans were going to do it with the full Hollywood pizzazz! I bet you a third of their budget would be publicity; and the BFI would be all very modest and home spun. Why should I do it? - what is going to be the consequence? CD: The first reason I cannot tell you because that would be very contentious at this point; the second and third reason I can tell you, which are: this is what Kevin said – “The Americans are not going to do it complete. They are linked to a three and a half hour format because of the golden hour”, and then later when I finally met Francis Ford Coppola, (in that story that Jean Davis began to tell you, when he thought that I was somebody else), in that meeting I said ”I thought you were in the middle of a deal to acquire a complete showing”. He said “What do I want a deal for – three and a half hours is fine by me – I would have to re-edit the film and I would have to spend a lot of money!”; he was quite right: I would have to record extra music, would have to commission extra music, have to remake the print, etc.. But before that Kevin said that it is not the complete film; we have the opportunity to screen the complete film or, as it was never complete, as much as I have which, at that point, if you screen it at 20 frames, would give us nearly five hours. I agreed, I think that is valid. |

|

The American Screening | |

|

The other reason: Kevin said “When the

Americans screen it they are going to do so at 24 frames, and we have been

making such a case for adjusting speeds so that the speed was correct”. So I

felt in the light of that it will be different enough, in those two ways at

least, to say that it will be artistically more viable; it will look better,

and it will present the complete case for as far as we can possibly go. ML:

The best version you could get. CD: Yes, given my total inexperience, and learn as you go. But we all agreed that in the light of the, by then, four years we had been working together that artistically the choice of music, how we were intending to do the music, what I was going to compose, what I was going to draw on; we already had a very strong working vocabulary, which was going to extend into "Napoleon". That was the story of the start of it then, as its history went on, the Americans had a huge success; there is no question they had an absolutely huge success; and so did we in our version. The Theatre we did it in – the Empire, Leicester Square – booked us to do four more performances in March 1981 and we were at Edinburgh Film Festival. We then had the French screening, La Havre, followed by Paris - they were tremendously successful. |

|

Where the thing shut down | |

|

We knew that moving outside of England we had

to actually do it via Images, and that happened. We were in Israel, in

Athens, Helsinki, Lausanne, Luxembourg, Hong Kong – it was extraordinary.

Then in its history - the crisis - which in a way provoked a solution; a

clarification came when Carmine died, it became very difficult to get

permission to do the performance. ML: part of his grief? CD: It became his lasting memorial, apparently. I did make a bid saying to him that we should co–exist but he felt that he had a moral conscience – the word morality came into it - something along those lines; I have forgotten exactly his words. You sense that he had an obligation to protect his father’s blessed memory – it was serious stuff. We did it in 2001 in Pordenone in Italy, and Coppola tried to ban it – but the Italians put pressure on him saying that if they withdraw it “you will bankrupt an Italian Film Festival”! ML: – So that it was moral blackmail in reverse. CD: That helped us there, but when it came to the 2004 showing, which was part of a series I was doing with the London Philharmonic – an annual film we were doing at the Festival Hall – the same thing happened. I am not sure how we scraped through that, but I thought I was going to wake up with a horse’s head in my bed!! Something awful was going to happen; should I hire minders? should I have security guards around me! but it went forward, although there was protest. Then followed the very aggressive attack on it. ML: Kevin made a speech – before the last screening in the Festival hall – he likened him to Dr. Goebbels – CD: Yes, I had heard Mussolini but that was to his face - ML: Mussolini for the Italian connection. CD: Yes. ML: But Dr Goebbels, the man who banned it, how can a filmmaker do this? CD: Well take my point of view – rights or not in the film - I know that the question of the music was really a very sore point, and I can understand that. ML: It was to his genuine grief? CD: Yes sure: I have to say we knew, but I have to take as a reason that our production was going to be different. I thought that was valid: and I still say that was valid - assuming that they had the rights - and at that point there was apparently a document. When it came to investigate no one could find this document, and Anthony Smith was now safely ensconced in one of the Oxford colleges. ML: So nothing to show in court? CD: No. ML: Now the future – after San Francisco – what can we look forward to? CD: There will be a performance in London on 33rd Anniversary, November 30th, 2013 ML: and a Bluray, DTS, Dolby, ? CD: Yes, I thought that was on, but as soon as the legal question had been resolved, we had the bitter thing with Coppola, Kevin was in the position of their demanding to have all the extant material, and he was in the middle of doing this. To suddenly make a DVD, and this would probably have been with Coppola’s score, perhaps extended, the whole thing was dropped midway – it was just dropped! There were financial implications that no one was going to accept. Apparently there is only an illegal version, i.e. the Channel 4 screening - not having any idea that there would be a problem way back in 1982 - no it must have been 1983, because part of its ongoing story is that after many years in which the French regarded Kevin as a “voleur” (thief) – they finally allowed him into the Cinematheque to look at new material! So from that point which I think was 1983, the film went into its next phase because Kevin found material that was not included, that he wanted to include, and most interesting thing of all he found Gance’s own story order, scene order, which was different. He had presented things initially in what he thought was the correct historical order, but in fact they were not; so a lot of things had to be moved around and material added so there followed then quite a radical overhaul of the whole score. |

|

The 2000 Screening | |

Then there was the third overhaul on it for

the 2000 screening, which was at the behest of the Archives of the World, in

London in 2000; then there was a further overhaul – people kept nibbling on

it – (Patrick now) – so I was always in torment because each change has to

be followed through by a change in the score, and the parts to match it.

This is less awful now than it was when you were snipping and pasting; now

everything is on computer so adjustments can be made much more easily - for

instance, I know Kevin will premier something like seven seconds of an

extension of a shot in the school room in the first part. Then there was the third overhaul on it for

the 2000 screening, which was at the behest of the Archives of the World, in

London in 2000; then there was a further overhaul – people kept nibbling on

it – (Patrick now) – so I was always in torment because each change has to

be followed through by a change in the score, and the parts to match it.

This is less awful now than it was when you were snipping and pasting; now

everything is on computer so adjustments can be made much more easily - for

instance, I know Kevin will premier something like seven seconds of an

extension of a shot in the school room in the first part.ML: That is part of the publicity, the appeal – yet more material has got to be found and it will never end. CD: When did you do your interview with Kevin? – ML: last October? - CD: He already had his seven seconds! – people are still finding things in attics – someone in Denmark had found an entire print in an attic. ML: I guess that is it – except for a quote from Arthur Schopenhauer, the German philosopher, where he says – “talent hits a target no one else can hit; genius hits a target no one else can see” So, many, many thanks on behalf of - “in70mm.com” - for affording us this marvellous opportunity to discuss this greatest of all films, and scores! CD: Thank you! |

|

• Go to Carl Davis: “All Art aspires to the condition of Music” |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |