Projecting “Napoleon” – une pièce de resistance |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written and photographed by: Mark Trompeteler | Date: 05.02.2011 |

Triptych

On Screen Triptych

On ScreenScreening “Napoleon” can be amongst the bigger projection challenges for any projection team. Mark Trompeteler reports on how three 35mm projectors and projectionists, a PowerPoint presentation, a full symphony orchestra, an organist, a pianist and a DVD based timecode all come together for a screening of the 1927 silent film masterpiece, and a piece of Cinerama and widescreen pre history. |

More in 70mm reading: 65mm Film: The Fabric of Magic. Part 1 – The Kodak View "Oppenheimer" Reviews Carl Davis Interview Abel Gance’s "Napoleon" Presented in “Polyvision” “Napoleon”: The North American 70mm Engagements We saw NAPOLEON on Sunday in Amsterdam "Napoleon" in Triptych was an Absolute Triumph “Napoleon" in San Francisco Kevin Brownlow Interview - Part 1 Kevin Brownlow Interview - Part 2 |

Triptych

Screen Triptych

ScreenEver since I developed a keen interest in cinema, I had known of the importance of French film director Abel Gance and his place in the development of film language and the history of cinema. I had read much of his silent film masterwork “Napoleon”, particularly since the tumultuous reception of Kevin Brownlow’s and the British Film Institute’s legendary restoration of the film and their presentation of it at the 1980 London Film Festival, and the restoring of its reputation as a true masterwork of cinema. |

|

Central

Main Panel on Screen Central

Main Panel on ScreenI never got to see it on the big screen in the eighties as it should be seen, despite the equally legendary screenings of it at The Empire Leicester Square, in March 1981 in London. I did see the film on television on a weekday afternoon, I think it was in the mid to late eighties, as part of a Silents season, and even on a tiny screen I was so impressed with this masterpiece. |

05.02.2011 Hi Mark Congratulations on an excellent article, which will increase interest in this important strand. Polyvision was very much ahead of it's time- September 30th 1952 to be precise. Nothing in cinema after that date would ever be the same. Best Regards, Mark Lyndon PS. After the interview, KB and I went out for a drink. It was a bitterly cold day, so I put on my Panavision hat and KB donned his Cinerama hat! |

Philips

FP20 Projector Philips

FP20 ProjectorI had always wanted to see the Brownlow restoration on the big screen as it is intended to be seen. When Barry Wright and Steffan Laugharne, the intrepid Bell Theatre Services projection team, kindly invited me to attend and observe them on a technical rehearsal of their presentation of the film – I seized the chance. Ian Nichol was the third member of their projection team. The other very interesting thing about projecting “Napoleon” for readers is the challenge that projecting the film represents. |

|

Some Challenges | |

Triptych

Polyvision Screen Triptych

Polyvision ScreenAmongst some of the challenges for the projection team in this presentation of “Napoleon” were: the sheer length of the film ( 5hrs. 32mins.), the fact that being a major silent film it was being accompanied by a symphony orchestra and an organist with accompanying timing and synchronisation issues, the fact that despite it being a French masterwork, arguably the best print of it available in the world is this Brownlow / BFI one which has English titles throughout, thus hundreds of titles need to be shown translated into other languages should the need ever arise, and also the final legendary three image triptych that bursts onto the screen, in the closing twenty minutes of the film. |

|

Steffan

Laugharne Steffan

LaugharneThe three projector and three panel images on the screen of spectacular panoramas and collages were Gance’s experiment with his “Polyvision” process – that was premièred at The Paris Opera in April1927, predating the première of Cinerama by a quarter of a century. Patrick Standbury, Kevin Brownlow’s partner in Photoplay Productions, who supplied the print, was attending the technical rehearsal and screening and overseeing the whole presentation, as well as taking particular responsibility for the sychronisation of projected image on screen and the orchestra. |

|

Restorations and Scores | |

Specially

Built Projection Box Specially

Built Projection BoxThe story of the restoration of Gance’s epic masterpiece is something of an epic in itself and I can thoroughly recommend Kevin Brownlow’s book “Napoleon’’ (Abel Gance’s Classic Film) .The current Brownlow / BFI restoration at 20 fps completed in its current form in 2000 runs at 5 hours and 32 minutes with the famous twenty minute triptych last sequence available in three 35mm panel prints complete with colour tinting as Gance had originally included. The master material is all from a negative and this latest restoration is largely based on the restoration of 1982 which ran at 5 hours and 15 minutes which in turn was based on the first original restoration by Kevin Brownlow in collaboration with the BFI and the National Film Archive which was the 4 hour 50 minute version that made its debut at the London Film Festival. Thames Television commissioned Carl Davis to compose a new and original score for “Napoleon” as part of its investment in the legacy of silent film and it was this that accompanied the film at the 1980 London Film Festival and the four subsequent screenings at The Empire in March 1981. The role of the late David Gill, Kevin Brownlow’s then collaborator and partner in Photoplay in promoting the legacy of silent cinema also cannot be underestimated. |

|

Silent

Film Orchestra & Central Panel Screen Silent

Film Orchestra & Central Panel ScreenThere are two other restorations of the film - a French restoration undertaken by Gance himself and Claude Lelouch dating from 1970 – 1971 utilising a French score by Arthur Honegger and Marius Constant which incorporates some of the original music from the twenties, and the American (24 fps) restoration undertaken by Francis Ford Coppola and Robert Harris with a score by Coppola’s father. My friend and acquaintance Eric White in Melbourne had recounted to me how in the original “showcasing the restoration” season in Melbourne years ago, with a live symphony orchestra, the last reel and triptych were presented on 70mm. When he saw it again at a later season at Monash University, with Dolby sound, on that occasion the climactic reel was on 35mm, projected with an anamorphic lens and an aspect ratio of about 3:1. They put in a special screen for the occasion as was done for this recent screening. I considered myself lucky being able to witness a screening of what is arguably the definitive Brownlow/BFI restoration, even if on this occasion, it was not going to be shown with its excellent Carl Davis score. |

|

Projection | |

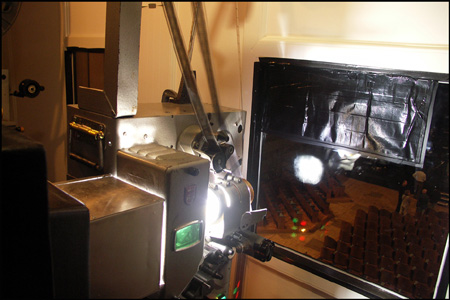

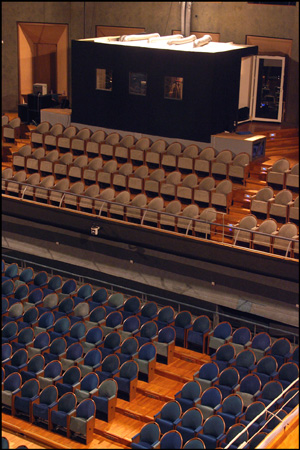

Three

Projectors Three

ProjectorsThe venue for this particular screening was the auditorium of a modern concert hall with a seating capacity of 1000, however for this special screening the capacity had been reduced to 650 due to sight line problems, not so critical when listening to a concert but obviously crucial for a film. A special projection box had been built in advance and installed towards the rear of the auditorium after much prior liaison and specification from the projection team. The box was of upvc construction with the necessary three portholes for the triptych and with extraction hoses going up to the high ceiling of the concert hall and outside to facilitate the extraction from the three projector lamp houses. |

|

The

Three Projectors The

Three ProjectorsThe screen that had been constructed was 16 metres wide by 4.1 metres high and the revelation process for the projection of the ultra wide triptych sequence was being done by curtains and a pulley system. The curtains would open at the right moment to reveal the very wide screen for the last twenty minutes of the film. |

|

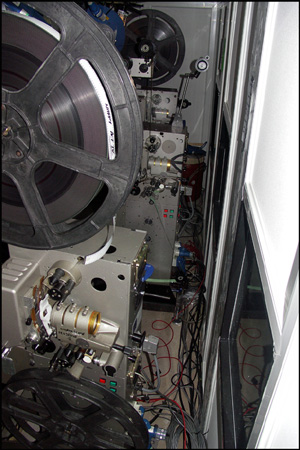

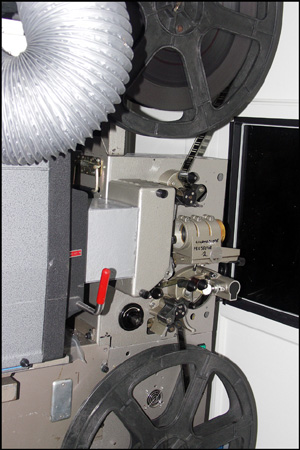

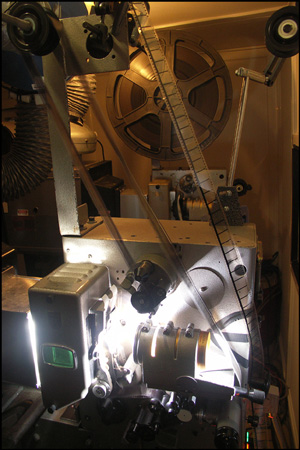

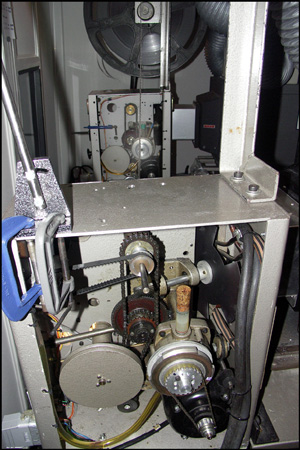

Philips

FP20 Projector Philips

FP20 ProjectorBell Theatre Services had three Philips FP20 projectors and all the necessary equipment required by the projection team shipped over to the venue. The team worked hard to rig up the projection box ensuring everything would be in place for this mammoth projection session. The venue’s health and safety policy came to the fore when the box was visited a couple of times by the venue’s health and safety officer to ensure everything was being considered in terms of these issues. |

|

Projector

running an alignment loop Projector

running an alignment loopThe projection lenses used were 145mm focal length with the projection distance being 38 metres. The projectors had 7kw lamphouses and water cooled gates with the central projector working with a tower, and the left and right hand projectors working with 6000 foot spools. The three Philips FP 20s were specially adapted to have three blade shutters. When silent films are projected at slower linear speeds (20, 18, 16, fps) flickering can become apparent and these shutters help prevent this. |

|

Synchronisation | |

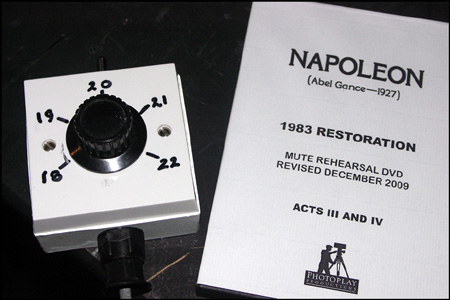

Using

Reference DVD Timecode Using

Reference DVD TimecodeThe central (middle triptych panel) projector was fitted with a variable speed motor that could be controlled remotely from nearby. The left and right hand projectors had their variable speed motors “slaved” to the central projector’s variable speed motor. What this facilitated was twofold. During most of the projection of the film the central projector would be used and its speed could be adjusted very subtly and remotely from nearby. During the final “act” of the presentation all three projectors would be used and any subtle variation in speed adjusted on the central projector would also be effected on the left and hand right projectors. This was the basis of how synchronisation of the various ingredient parts of this magnificent screening was going to be effected. |

|

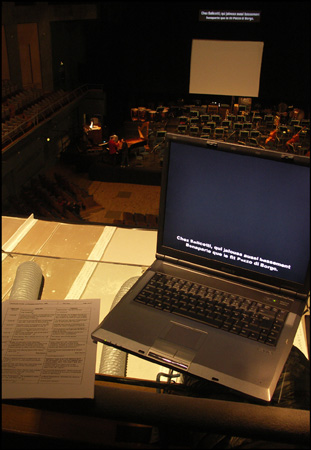

Operating

the sur titles Operating

the sur titlesClose to the projection box in the gallery, in a position with a good view of the screen and the orchestra, a chair, a dvd player and a monitor and a simple variable speed controller had been set up. Patrick Stanbury from Photoplay had a timecoded reference DVD of the film which he could run in front of him and compare the place in the film on his monitor with what was on the concert hall screen with the time code clearly displayed on the monitor. His variable speed controller could adjust the speed of the projectors by 2fps plus or minus either side of the print’s projection speed of 20fps. |

|

Timecode

Workstation Timecode

WorkstationThe conductor, the organist and the pianist in the orchestra all had small black and white monitors beside them so they could see both the timecoded image on their monitor and the image on the big screen. Prior notations on their various music scores already had reference points to where they should be with the score at various points in the film and their references worked to the timecode. The timecode and the ability of Patrich Standury to very subtly speed up or slow down the film to keep the orchestra, organist and pianist and film in synch was simple and effective but something that most projection teams don’t have to worry about normally. In addition Photoplay had supplied the projection team with a number of triptych alignment loops of 35mm film that could be laced and run on all three projectors so the projected panel image could be aligned on all of the screen before the performance in order to make the triptych panorama scenes at the end as effective as possible. |

|

Titling | |

Surtitles

on Laptop Surtitles

on LaptopOne other important component of the presentation was the translation of the 450 titles back into the French language. It is ironic that the definitive restoration of this French masterpiece was undertaken by the English. This irony did not escape the two women who sat in the gallery above the projection box with a laptop and a PowerPoint presentation of all the titles translated back into French. Using a video projector sur-titles of the total translations were projected above the screen with no more than hand and eye co co-ordination, on screen reading and a nearby script to effect the synchronization of the translated sur-titles. |

|

A Magnificent Mammoth Screening | |

Final

Reel Spacer plus toned triptych print Final

Reel Spacer plus toned triptych printOne projection problem that also had to be dealt with was to do with how the print had been printed at the laboratory. In this restoration the frame line had a tendency to wander up and down the screen image a little, and in order for this not to spoil the viewing experience, the projectionists had to constantly monitor the racking adjustment control and constantly make minor adjustments. After five and half hours of this and some significant discomfort in the hand and fingers the team came up with a newly diagnosed projectionists’ industrial injury – RRS - repetitive racking syndrome. |

|

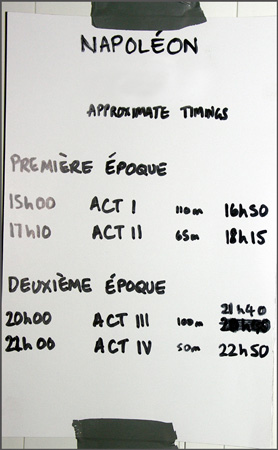

Approximate

Timings Approximate

TimingsThe screening of this restoration “Napoloen” is done in four acts, with a short interval between acts one and two and acts three and four. Between acts two and three a longer intermission is scheduled so the audience can have a meal or snack, since if the running time of the film is five and a half hours, then the whole performance with intervals is going to be a lot longer, hence the need for a central meal or snack break. |

|

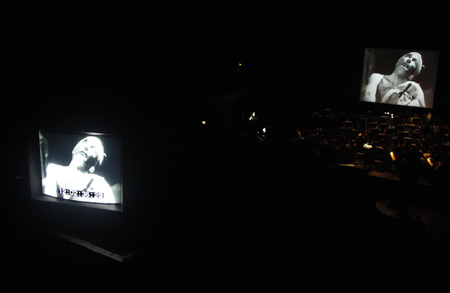

Triptych

On Screen 2 Triptych

On Screen 2The final act of 48 minutes involves the final twenty minutes of three panel “Polyvision”. To effect this all three projectors are laced with synch points on the prints aligned and have their lamps “struck”. Whilst the central projector obviously projects images for the entire 48 minutes, the left and right hand projectors have black spacer film running for 28 minutes – since all three motors are slaved they keep in synch and at the appropriate moment the three panel images suddenly burst onto the screen, the curtains rapidly drawn back and the full width of the screen is revealed, (the “This is Polyvision” moment.) |

|

Variable

Speed Controller Variable

Speed ControllerAttending this screening for me was a fabulous experience and it showed me how much projectionists can be committed to their work and how it can give so much satisfaction. Projecting this magnificent restoration of “Napoleon” must be one of the major challenges for any projection team – and the Bell Theatre Services team executed it brilliantly. Also one can never praise the work of Photoplay & Kevin Brownlow enough. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded a special honorary Oscar to Kevin Brownlow in November 2010 with the citation read by Kevin Spacey, at the Academy’s 2nd Annual Governors Awards dinner. “Each of these honorees has touched movie audiences worldwide and influenced the motion picture industry through their work,” said Academy President Tom Sherak. “It will be an honor to celebrate their extraordinary achievements and contributions at the Governors Awards.” |

|

Slaved

Motors Slaved

MotorsAttending this screening also led me to think as to how in the popular history of cinema, and widescreen cinema in particular, much is quite rightly made of the work of Fred Waller and the development of Cinerama and how Cinerama forced the development of the widescreen revolution. But does Abel Gance get the recognition he deserves in the popular history of Cinerama and widescreen cinema? Seeing this screening of “Napoleon” underlined in my mind at how Gance’s experiment with Polyvision and its successful public screenings predate “This is Cinerama” by 25 years. Surely, apart from a curved screen, to all intents and purposes and fundamentally Waller’s Cinerama is Gance’s Polyvision triptych by another name? |

|

Thanks | |

%20Ian%20Nichol_%20Barry%20Wright_%20Steffan%20Laugharne.jpg) (L

- R ) Ian Nichol_ Barry Wright_ Steffan Laugharne (L

- R ) Ian Nichol_ Barry Wright_ Steffan LaugharneI must express my sincere thanks to Barry, Steffan and Ian, the Bell Theatre Services team, and Patrick Standbury of Photoplay, who so very kindly allowed me to attend this magnificent screening. Related Websites: www.photoplay.co.uk, www.bell-theatre.com Recommended Reading: “Napoleon’’ (Abel Gance’s Classic Film) by Kevin Brownlow, Reprinted and published by Threefold Music 2009, ISBN 978-1-84457-077-5 An excellent and fairly recent interview with Kevin Brownlow by Mark Lyndon can be seen at the website: www.in70mm.com. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |