Why 70mm Matters |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Brian Walters, Australia | Date: 04.02.2017 |

During the 1950s and 60s, the large negative 70mm release print format was

ubiquitously associated with epic films produced on a grand scale, such as “Ben

- Hur”, “Around The World In 80 Days“,

“My Fair Lady“ and

”2001: A Space

Odyssey”. When a production was announced to be captured on 65mm negative it put

the film crew on notice of the level of commitment expected which had a knock on

effect on all aspects of the production. When David Lean took

Super Panavision

70 cameras into one of the most hostile environments on Earth, the Jordanian

desert, to film his masterpiece “Lawrence Of Arabia“, he did it knowing that

this would be one of the most difficult and challenging film shoots ever

undertaken. He also knew that no other format would fully realise his vision of

the film, one which has proven to be the bench mark of large negative 70mm

productions. During the 1950s and 60s, the large negative 70mm release print format was

ubiquitously associated with epic films produced on a grand scale, such as “Ben

- Hur”, “Around The World In 80 Days“,

“My Fair Lady“ and

”2001: A Space

Odyssey”. When a production was announced to be captured on 65mm negative it put

the film crew on notice of the level of commitment expected which had a knock on

effect on all aspects of the production. When David Lean took

Super Panavision

70 cameras into one of the most hostile environments on Earth, the Jordanian

desert, to film his masterpiece “Lawrence Of Arabia“, he did it knowing that

this would be one of the most difficult and challenging film shoots ever

undertaken. He also knew that no other format would fully realise his vision of

the film, one which has proven to be the bench mark of large negative 70mm

productions. This format however only a few years ago was on the brink of extinction due to the world wide rollout of digital projection systems in cinemas. Amazingly however the 70mm format has experienced a phoenix like re - birth due to the efforts of film makers like Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino, who have against the odds, released films using the large negative 70mm release print format, after being instrumental in brokering a deal with the six major Hollywood studios to guarantee the availability of Eastman Kodak film negative for a further five years. It is an exciting time for lovers of the 70mm format with productions recently released, in production and announced for production in the 70mm film format, because of the efforts of these and other film makers. This situation has not occurred since the late 1960s, despite the closing of most of the large 70mm equipped auditoriums that showcased 70mm Roadshow productions in that era. When key cinema venues close, such as the Imax 15 / 70mm cinema in Sydney Australia, which had the largest Imax screen in the world, they are more than just closures, they are losses of relativity. Their existence is the required connection between production and large negative 70mm exhibition, and are the vital final link in the theatrical film release chain. Without them, discerning cinema audiences don’t have the option of seeing high quality large screen film presentations, giving them the opportunity of comparison to digital presentations. Currently in cinemas there are three types of presentation, films shot on film and presented on film, films shot on film and presented digitally and movies captured digitally and presented digitally. All three of these have different characteristics, because they are inherently different to each other, and then other compromising factors such as silver screens for 3D presentations installed into many cinemas in a knee jerk reaction to the success of “Avatar“ also come into the equation. This unfortunate silver screen saturation now in cinemas, which in some complexes is upward of 90%, not only inhibits accurate colour rendition for all non 3D presentations, but also introduces a range of issues with screen illumination and light uniformity. Stereoscopic imaging which has been experimented with since the early years of cinema and which has had two major release windows, firstly on film in the 1950s and then in the late 2000s in it’s current digital incarnation, has often in the publics’ eyes been regarded as somewhat of a gimmick, reserved for “coming at you“ special effects, rather than being a cinematic tool for an improved theatrical experience. Interestingly the two most commercially successful movies for each of these two periods were “The House Of Wax“ in 1953 and “Avatar“ in 2009, both the first major productions of these two resurgences. This can be attributed to the fact that once viewed the novelty of 3D is gone and the audience attraction for the format would appear to be diminished for subsequent releases. Over the last two years especially, there has been a dramatic roll off in audience interest in 3D presentations, with fewer and fewer sessions now scheduled for 3D releases and the 2D version of any 3D available movie now far more popular, which is a complete turnaround from the box office performance of “Avatar“. The recent HFR, High Frame Rate, 3D release of “Billy Lynn’s Long Half Time Walk“ has met with indifferent reviews similar to those for the HFR 3D version of “The Hobbit“ where the hyper realistic images make the viewer acutely aware that they are not watching a normal nor natural presentation, which ultimately is more of a distraction rather than an enhancement, making the overall experience seem more sideshow than theatrical . While there are those who view 3D as the future of cinema, if the decline in popularity continues at it’s current rate, the reality may well be it could once again become the past, as history repeats itself to await yet again for another generation of cinema goers to be amazed by the “new“ must see screen wonder. |

More in 70mm reading: Around The 70mm World In Thirty Seven Days The 70mm Trailer Anomaly Internet link: |

Click

the poster to see enlargement Click

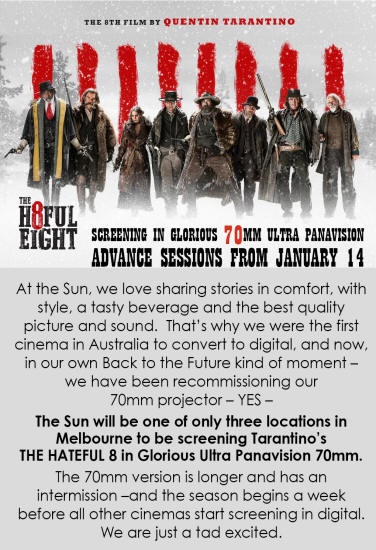

the poster to see enlargementBy stark contrast, in recent times there have been a number of cinema productions captured on 16mm film, such as “Suffragette“, “Carol“, “Anthropoid“ and “Jackie“ ,and one might wonder why a film maker would in this day and age choose to do this, rather than shoot high definition video which would be more economical and have higher screen resolution ? This is because some film makers realise there is a lot more to picture quality than resolution, “digital does not need more pixels, it needs better pixels“ , as has been stated elsewhere. The colour saturation and contrast of film capture can’t currently be matched by that of digital, then when you go from a 16mm negative capture to a 65mm capture the benefits are exponential. This superiority of the film format is what digital capture has always been chasing and continues to do so, with improved camera sensors and the proposed REC 2020 colour space now under discussion for cinema use in HDR, High Dynamic Range, formats such as Dolby Vision. However the Rec 2020 colour space will only be properly projected by digital RGB laser projectors that are currently prohibitively expensive and represent less than one percent of digital projectors installed in cinemas. The move away from white light xenon based digital projector light sources that currently support the P3 digital colour space standard, will be a very slow transition as these projectors are still relatively new, making their redundancy economically difficult to justify and afford, especially as the VPF, Virtual Print Fee, arrangements where film distributors subsidised the installation of digital projection systems in cinemas come to an end. Advocates of digital capture often use the phrase “a film like appearance“, when talking about the most recent advancements in this technology, and that the gap between the two technologies is always reducing. This opinion only holds true of course if you regard film as a static technology, but with the Eastman Kodak film company now with the wind back in its’ sails, it can be assumed that it will again be putting resources into research and development to improve their products, as has always been their policy. Are Kodak Vision 2383 & 3383 film emulsions the ultimate release print film emulsions ? I wouldn’t think so. Are Kodak Vision 3 negative emulsions as good as they can be ? I’m sure Vision 4 is coming, and are the current Estar Polyester release print film bases lossless ? Film lovers can look forward to new and exciting products from the company that has always lead the way to further enhance the theatrical film experience in the years to come, just as new and improved film laboratory processing techniques will also continue to improve the film experience producing ever higher quality release prints. |

|

Click

the poster to see enlargement Click

the poster to see enlargementIn a recent article from the newly appointed president of Kodak Motion Picture Entertainment, Steve Bellamy, entitled “Be a Film Maker, Not a Video Maker“ in which he explains many of the obvious and not so obvious reasons to shoot on film, he highlighted the artistic differences of the two mediums. “Film is an artful medium for creating art and digital is the medium for capturing content“. The difference has never been more obvious than after seeing “The Hateful Eight“ in 70mm projected onto a white screen and then going to see a digital presentation afterwards. The 70mm release print format also has the great advantage of providing a theatrical experience that cannot be duplicated in your lounge room. Do cinemas advertise a digital presentation being in 4K resolution, its premium digital cinema offering ? Well rarely, because many people already have this on their television set at home with a colour space close to the P3 digital cinema standard. Will “Magi Cinema“ be available for home entertainment in years to come ? This would only require increasing the television refresh rate from 200Hz currently for 3D televisions to 1000 Hz for high frame rate home entertainment 3D, it’s only a matter of applying electronics technology to make it happen. Any digital based format can be transferred to the home entertainment experience because they both rely on the same technology base, only the pre - eminent qualities of film can set cinema apart from home entertainment. This fact is what lead director Quentin Tarantino to lament to French journalists at Cannes in 2014 why he felt that for him cinema was dead, “because all you are doing now is watching television in public“. This lost point of difference that cinemas once had is one of the big marketing advantages that 70mm theatrical film presentations have over digital presentations, whose look has a sameness about it with what people see every day at home. The theatrical 70mm format cannot be transferred to the home environment and this cinema exclusiveness and unique theatrical look is what is driving the current wave of enthusiasm for the format with film makers and audiences around the world. When a cinema patron buys a premium priced admission ticket they feel like they are getting better value for money if they are about to experience something different and special, and 70mm delivers this. Visionary film makers want their films to stand out from the crowd, and shooting and releasing in the 70mm format achieves what digital can’t, a point of difference. It must be noted that “The Hateful Eight“ was photographed using Ultra Panavision 70 lenses that were over fifty years old and still managed to produce images with a quality exceeding anything we have seen from digital photography. When examining the box office performance of “The Hateful Eight“ from a film distribution stand point, it is difficult to determine from the available data whether the overall performance was increased by the fact the release was in 70mm film print format as well as the now conventional DCP, Digital Cinema Package, format. For the distributor they are looking at the bottom line, which can only be improved by increased admissions or an increased ticket pricing, or both, when considering future 70mm film release strategies. For “The Hateful Eight“ a premium ticket pricing was employed to help offset the considerable added expense of a wide 70mm print release. Did the 70mm format however grow the market, or did it simply move market share around ? Did the 70mm format bring patrons to cinemas who would have otherwise stayed at home and waited for the home domestic release on DVD and other digital platforms ? While the determination of increased admissions is somewhat speculative without hard evidence available, some anecdotal evidence may provide an insight. The “Sun Theatre” at Yarraville in Melbourne Australia continues to screen “The Hateful Eight“ once a month on the 8th at 8:00 PM. I attended the screening on November 8th. 2016, some eleven months after the film’s initial release which happened to fall on a Saturday night, so I was expecting maybe an audience of possibly fifty people. I was quite amazed however that the session in cinema one, the largest auditorium of this eight screen complex, was sold out to a very enthusiastic audience that broke into applause at the film’s conclusion. Would a similar movie released in digital format only, many months after it’s release on DVD be an economically viable option for a commercial cinema to screen again in digital? I would very much doubt it. This example though far from being conclusive evidence does show the potential of specialised presentation and marketing, and should be something carefully considered by film companies for the release of major productions. |

|

Click

the poster to see enlargement Click

the poster to see enlargementThere also appears to be a growing public interest in not only filmed analogue entertainment, but with 2016 showing a 200% increase in the sales of vinyl records worldwide also. This analogue sound format that like film, was on the brink of extinction with the introduction of domestic digital sound formats in the 1980s is experiencing a major revival that first starting gathering momentum in 2006. Whether this is due to a need for something tangible rather than just a downloaded playlist on a computer screen, or whether it’s more for the warmer full bodied sound that analogue delivers, this much revered format of audiophiles appears to be on the way back. While digital has proven to be the medium of social media, it may not necessarily be the exclusive medium for premium audio visual entertainment, where something more than ones and zeros is being sought after by some sections of the paying public. A balance of analogue and digital choice may be required to satisfy all tastes and markets. The decision to close the door completely on film, as was the strategy adopted by the major exhibition chains and motion picture distributors with the digital roll out, may now, due to a nostalgic longing by film fans and the creative choices required by film auteurs be something to be re - assessed. There would appear to be a case for digital and film formats to co - exist where a specialised presentation format is desirable to drive a more theatrical marketing campaign for certain big budget productions. You will sometimes see the marketing campaign “only in cinemas“ because it is a first release movie, but it could also be used because of the presentation format. Repertory cinemas such as the Prince Charles Cinema in London have shown this to be the case in the back half of 2016, when they installed 70mm film capability once again, after some earlier prompting by Christopher Nolan and Paul Thomas Anderson, to show a host of much loved 70mm film titles in recent months. British film makers Christopher Nolan and David Lean, though generationally separated, both epitomise the single minded resolve some film makers can have in their pursuit of film making excellence. In July this year when Christopher Nolan’s epic film “Dunkirk“ releases captured entirely on 65mm negative, both horizontally and conventionally, audiences will again have the opportunity of seeing film based cinema at it’s very best when it releases in Imax 15 / 70 and conventional 70mm release prints around the world. Following on from the release of “The Hateful Eight“ where almost 100 cinemas in North America were equipped for 70mm projection capability for it’s release, the work flow is now in place for a wide release of 70mm prints giving audiences the opportunity to experience the premium cinema release format once again. Recent news of the new 65 / 70mm laboratory capability at Cinelab in the UK for large negative film processing not only for “Dunkirk" , but also for Kenneth Branagh’s upcoming remake of “Murder On The Orient Express“ also now announced to be shot in 65mm, now offers film makers large negative film making processing facilities on both sides of the Atlantic. When examining the movie capture formats of the previous six months and looking ahead to those announced for the next twelve months there has been a noticeable move back to film capture of all gauges when compared to the previous two years. It is by no accident that all of the essential elements required for film capture and production are coming together again so quickly, as the movie making fraternity once more embraces the efficacy and quality of film to bring back the allure of cinema. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |