|

| |

Restoration of "My Fair Lady"

"What a gripping, absolutely ripping moment."

|

This article first appeared in

..in 70mm

The 70mm Newsletter |

|

Written

by: 20th Century Fox's press release about the restoration.

Prepared for in70mm.com by Anders M Olsson, Lund,

Sweden |

Issue 38

- April 1995 |

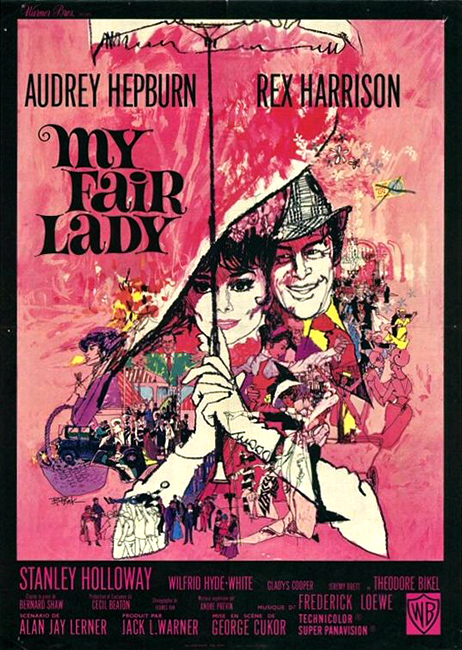

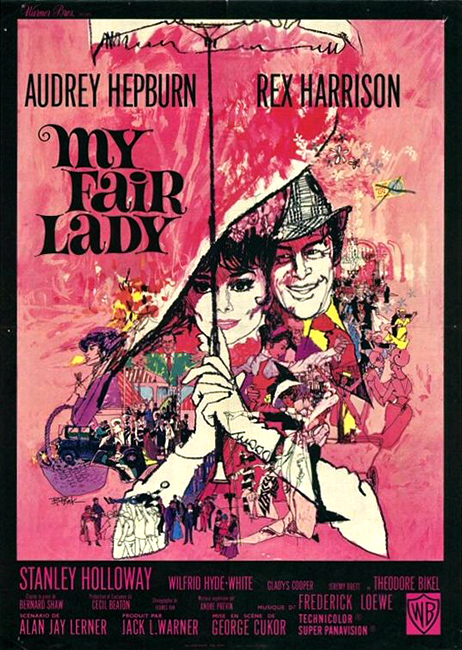

Artist

Bob Peck's "My Fair Lady" poster, 1964. Artist

Bob Peck's "My Fair Lady" poster, 1964.

In 1964 it was the quintessential American musical comedy - the tale of a woman

transformed and a man beguiled -- in which story, lyrics and music came together

in one grand sweep to create a totally encompassing entertainment.

In 1994 "My Fair Lady" has herself undergone a miraculous transformation from

tatters to splendor. Found disintegrating in a quake-ravaged vault in the

Northridge Fault Zone, the original camera negative was taken under the wing of

Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz, two film producers who have made a second

career of preserving cinema's pinnacle achievements with such acclaimed

restorations as

"Spartacus"

and

"Lawrence of Arabia".

Lovingly, painstakingly, the team worked to smooth "My Fair Lady's" rough spots,

restore her beauty and melody, and prepare the once torn and faded film elements

for its debut to a new generation of film lovers, both in a theatrical release

from 20th Century Fox and in a special home video edition from CBS Enterprises.

Although she is thirty years older, the great lady of American musical comedy is

now more loverly than ever.

In their efforts to rescue "My Fair Lady" from the brink of destruction, Harris

and Katz also discovered related treasures nearly lost to time, including rare

behind-the-scenes footage and the controversial and long-sought-after original

soundtracks sung by Audrey Hepburn before she was dubbed by Marni Nixon. This

material will become available to the public for the first time as part of the

restoration celebration.

"People who have seen the film have

never seen it like this," said Jim Katz. "And those who have

never seen it will be blown away by the performances, the music, the

kind of production value that could never be done today. It is 'My Fair

Lady' the way it should be seen in 1994."

When George Bernard Shaw wrote "Pygmalion" in 1912, based on the Greek fairy

tale of a man who unwisely falls in love with his own creation, he could never

have foreseen his simple moral tale would become the basis of the world's most

popular Broadway musical. Yet the story of Eliza Doolittle, the smart-mouthed,

spirited London street girl transformed into a ravishing sophisticate by a

cynical Professor, was universally appealing.

When Lerner and Loewe set the story to music it became a lyrical miracle --

witty and wise in prose and indelibly memorable in tune. "My Fair Lady" took

Broadway by storm in March of 1956 - and stayed there for some 2,712

performances over the next six and a half years. Throughout the late 50s its

songs were sung in almost every well known language in almost every city on

earth. Long before the mega-spectacles of today's Broadway, "My Fair Lady"

became an event, one that made theater seem fresh again.

Then, in 1962, it was reported that mogul Jack Warner had acquired the motion

picture rights for a whopping $5.5 million. There was enormous anticipation and

conjecture world-wide. Would Rex Harrison reprise his most famous role? Who

would play Eliza Doolittle on the screen? And could anyone possibly capture the

almost electric elegance and drama of the play on a movie set?

Production began in 1963 and lasted a full five months. It would be the most

costly and elaborate feature ever filmed by Warner Bros. -- a visual, musical

and technical undertaking of a proportion no longer seen in today's Hollywood.

At the height of production the majority of Warner Bros. soundstages were

devoted to "My Fair Lady" alone. Hundreds of seamstresses worked round the clock

preparing the costumes. And for the "Ascot Gavotte" sequence it took some 33

wardrobe persons just to get the cast in and out of their clothes.

Creating a screen

"My Fair Lady" to rival the Broadway production monopolized

studio resources and became priority number one. In retrospect, it is easy to

see why. The assembled cast and crew contained the créme de la créme of cinema

and theatre talent. Director George Cukor was already one of Hollywood's most

celebrated artists, a master of elegantly stylized drama and comedy, having

directed such classics as "Dinner at Eight," "Camille," "The Philadelphia

Story," "Holiday," "Adam's Rib" and Judy Garland's

"A Star is Born."

The legendary photographer and fashion innovator Cecil Beaton, who designed the

Broadway play, was the production designer. Beaton let his imagination go wild

on the more than 1,000 costumes, ultimately creating a London of such tactile

extravagance audiences would almost be able to feel the fabrics on the screen.

Gene Allen, long Cukor's right-hand man, was brought in as art director. Today

it is known that it was Allen, rather than Beaton, who was primarily responsible

for the creation of the sets, architecting a new Covent Garden, the lavish Ascot

Park and several English pubs in the process. André Previn, the composer and

conductor of renown, arranged the marvelous score which would go on to win an

Academy Award.

In front of the camera would be Rex Harrison, at the peak of his charismatic

career, having already won theatre-goers' hearts as Professor Higgins on

Broadway. Harrison was so beloved in the role that Cary Grant, when turning down

the studio's offer for the role, said he wouldn't even see the film if Harrison

wasn't Higgins.

And, in a stunning announcement that would create long-lived controversy, the

filmmakers announced that Audrey Hepburn, an international symbol of charm and

class in action, had been cast as the lowly Eliza Doolittle. Celebrated as an

actress but not a singer, it was a stunning and unexpected choice. Yet Cukor

said he saw in Hepburn a perfect match with George Bernard Shaw's description of

Eliza as "dangerously beautiful." The cast also included British stage legend

Stanley Holloway reprising his Broadway role as Mr. Doolittle and Jeremy Brett

as Freddie Eynsford-Hill.

It was clearly the cinematic event of the year. Gossip was rife about happenings

on the set -- would Audrey Hepburn sing her own songs? Did Rex Harrison really

request to perform his lines live with a wireless mic? Were George Cukor and

Cecil Beaton feuding?

It was also a time of enormous emotion when in November of 1963, just as the

crew was shooting "Wouldn't It Be Loverly?," news came of President Kennedy's

assassination. The crew attempted to continue but when Hepburn broke down in

tears, work was suspended for the day.

Even with its release, "My Fair Lady" did not stop monopolizing the news,

especially when it garnered some 15 Academy Award nominations, winning 8 Oscars,

including Best Director for George Cukor, Best Actor for Rex Harrison and Best

Picture of 1964. Only Audrey Hepburn was denied a nomination, which in itself

created a media sensation, especially after Julie Andrews (who created the role

of Eliza Doolittle on Broadway) took the Oscar for her performance in the year's

other great musical, "Mary Poppins."

Despite the hubbub, the consensus was clear: Cukor, Beaton, Allen, Previn,

Harrison and Hepburn had captured the excitement of one of the greatest moments

in musical history in a sumptuous motion picture that celebrated not only the

stage play but the very humanness of humans that Shaw's story illuminates.

|

Further

in 70mm reading:

Note from

Robet Harris and James Katz

"My Fair Lady" restoration credits

and a

comment

The Reconstruction and Restoration of John Wayne's "The Alamo"

Restoration of "Spartacus"

Restoration of

"Lawrence of Arabia"

"Lawrence of

Arabia" cast & credit

Internet link:

|

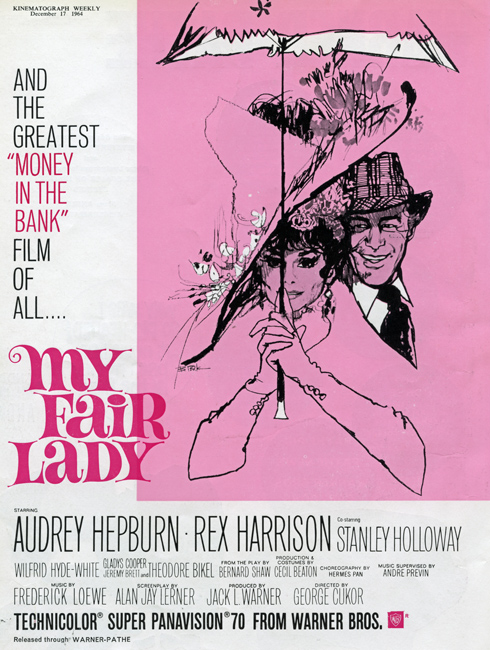

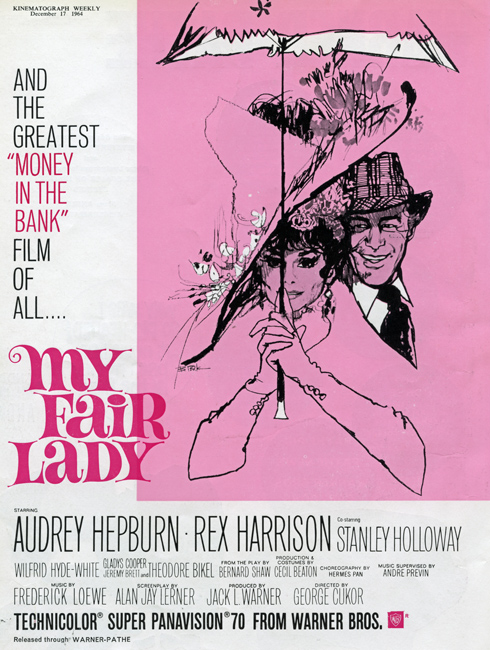

"My

Fair Lady" UK full page trade ad from Kinematograph Weekly, December 17,

1964. "My

Fair Lady" UK full page trade ad from Kinematograph Weekly, December 17,

1964.

Yet, a mere thirty years later what those tremendous artists had worked so hard

to capture was very nearly lost. Although there is a feeling that once something

is filmed it remains forever, it is sadly not the case. Images are fragile,

their colors and tones easily washed away, and celluloid grows brittle and old.

In fact almost 50% of all films ever made have been lost to the ravages of time.

"It is an outrageous thing that an

industry that is only 100 years old should have already lost so much,"

says Jim Katz. "Fortunately, things are better today. But the

conditions of prints just twenty years old can be abysmal."

To recover lost film, you don't call in a detective or an archeologist but

someone very akin to both -- you call in film preservation and restoration

experts such as Harris and Katz, two producers who have taken a special interest

in preserving state-of-the-art films from Hollywood's lavish era of large-format

features.

"It's a lot harder to fix a film than it is to make one,"

admits Katz, who has

produced such contemporary features as "Scenes From the Class Struggle in

Beverly Hills" and "Nobody's Fool." "You have to go into it not believing

anything, because whatever you find is going to just be the beginning of your

problems."

"What we do is part digging through history, part film production and part

science mixed in with a whole lot of bulldoggedness,"

-, adds Bob Harris, who is one of a

handful of people in the world with the skills to extract the buried

treasure that can lie beneath decades of dirt smudges, tears and neglect.

Currently, he is the world's foremost expert on fully restoring large format

films, including those shot in Super Panavision 70, a skill he particularly

relishes.

"Very few kids have seen a wide

format film but when they see the brilliant image of a 70mm print on a

70 foot screen they walk out of the theatre stunned. It's a whole new

experience," he says. "This was the last great large-format

musical of its time. There was nothing like it afterwards, and probably

will be nothing like it again."

Once they began on the project, Katz and Harris spent weeks rounding up every

surviving element of the film -- from daily continuity reports to the various

existing prints -- and found themselves crow-barring open vaults whose contents

had been upturned by the recent quake. Most of the material was held by CBS to

whom the rights reverted in 1971 (CBS originally financed the Broadway play in

order to produce the soundtrack album.) Unfortunately, much of the original

material -- including original soundtrack elements, main title elements, trims

and outs and B negatives -- had been thrown away.

"All we had at this point was a negative held together by tape and spit, and the

real work was about to begin," says Bob Harris. "It was up to us to figure out

how to put it back together the way it was meant to be."

The restoration itself took eight months of intensive research, digital

manipulation, sound re-recording and splicing negatives. It was as if Harris and

Katz had to take the film negative through the entire postproduction process

again -- only this time with the technology of the 90s at their disposal.

"The industry is more sophisticated today and so are filmgoers. There is a lot

that can be done to make a 30 year-old film look even better today than the day

it premiered," says Katz. "For example, 'My Fair Lady' is the first

reconstruction to take advantage of digital technology."

The main title sequences were marred by huge nicks and scratches including a

black hole under Jack Warner's name so big, according to Harris, "you could

drive a Buick through it." Once considered unfixable, these flaws were digitally

"erased" in the computer-lined studios of Cinesite, where digital artists turn

film into malleable digital information and then back again. By using digital

information, Katz and Harris could literally remove and replace individual

pixels, until the holes were patched without so much as a trace that they were

ever there.

Many sequences in the negative suffered from multiple frame tears. In some

cases, they were able to go back to the black and white separations to produce

new dupe negative. When that was not possible, they resorted to digital

restoration -- an extraordinarily expensive process that was used only for the

most horrific problems, such as the light spot that bounced around on Audrey

Hepburn's otherwise perfect face through parts of the film.

Even as Katz and Harris worked to fix the film, it continued to disintegrate.

The negative was so fragile that during the first attempts to reprint it, it

continued to tear and break. Sometimes, the only plausible option was to tape

the torn negative by hand. In each case, it was a matter of deciding what would

be best for the film.

"Everything can't be perfect and not all problems can be

100 % fixed," Harris admits. "There is no magic machine we can run the film

through to make it all right. In some cases, you just have to decide what would

be the least objectionable thing."

The team faced an equal challenge restoring the film's sound to the aural

brilliance and clarity so necessary to its full enjoyment. In 1964 it was

announced that "My Fair Lady" would utilize the most sophisticated sound

recording system ever used for a motion picture -- state of the art six track

recording. Harris and Katz wanted to use today's state-of-theart -- digital

sound and Dolby stereo -- to heighten the immediacy of the Lerner and Loewe

score even more. But as they prepared to re-record the picture's soundtrack, it

became apparent that the original vocal and music tracks had not survived. The

only sound available was a six track composite print master and a three track

foreign version of music and effects.

Most of the voices could be fixed, but today's sophisticated sound reproduction

equipment picks up even subtle background noises yesteryear's playback equipment

never revealed -- meaning Harris and Katz found themselves listening to flies

buzzing around on Cukor's set!

Other problems also arose with the sound, some of them having to do with the

production's colorful history. In 1964 it was reported that Rex Harrison refused

to lip-synch his musical numbers like all the other actors and insisted on

singing "live," performing each song in a single live take while wearing one of

the very first wireless microphones (which incidentally can be seen as a bulge

underneath Harrison's tie throughout the film).

|

|

"My

Fair Lady" playing in Super Panavision 70mm at the Max Linder Panorama,

Paris, France, summer 1990. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev "My

Fair Lady" playing in Super Panavision 70mm at the Max Linder Panorama,

Paris, France, summer 1990. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev

The unusual request may have forged a performance of sublime spontaneity and

presence, but it also caused major headaches for the restoration. Due to the

difference in technology, Harrison's "live" songs have a harsh and brittle

sound, not the lush, warm sound he would have had if he recorded them on today's

equipment. And the mic, though sophisticated for its time, ended up registering

such very un-Shavian sounds as police radio broadcasts and taxicab calls.

Still, the restoration team was cautious to use sophisticated new sound

technology only to preserve and not to add any newfangled effects.

"Obviously we were working with

Academy Award-winning sound so we didn't want to get too gimmicky,"

says Katz. "Our aim was to reflect the intention of the filmmakers to

the best of our technological ability."

One of the most obvious examples of how new technology was put to work to

enhance the original spirit of "My Fair Lady" can be heard in the famous scene

in which the horses fly by the grandstand in Ascot Park. Here the restoration

utilized state-of-the-art surround sound so that the sound moves with the

horses, from right to left, fading as they disappear. For the first time, the

audience can sense the full presence and power of the horses as they furiously

round the bend, something Katz and Harris feel certain the filmmakers would have

done if they could have in 1964.

Knowing what the original filmmakers would and would not have done is all part

of the process of properly restoring a beloved film. This is where the detective

work comes in -- the team not only dug through vaults and inspected mysterious

unmarked film cans but built an entire dossier on the production and all its

participants in order to understand everything they did.

They even tried to track down the costumes and sets -- discovering, among other

things, that there have been more unconfirmed sightings of Audrey's Ascot Park

dress around the world than Elvis sightings and that her famous ball gown is

gone forever, accidentally thrown into a dumpster when it was shipped to a

benefit in a Ralph's Grocery bag!

"We end up knowing more about the production than the people who were there,

because we're seeing everything, all the memos and audio tapes and

correspondence, and we have the advantage of hindsight," explains Harris. "We

find out what the problems were. In many cases we found that the truth doesn't

necessarily jibe with people's memories."

One of their truly astonishing finds are the original soundtracks sung by Audrey

Hepburn. Although it was widely reported in 1964 that another singer was going

to "help" Audrey with some of the higher notes, she was excited about doing her

own singing and trained vigorously with a voice coach. Only later was it

revealed that the vast majority of the songs were sung entirely by Marni Nixon.

Harris and Katz now believe that Cukor may have encouraged the belief that most

of the singing would be Hepburn's own in order to keep her spirits high for her

performance as the unsinkable Eliza Doolittle. They spent several months

recording her singing the songs, yet all along were planning on using Marni

Nixon.

"She has a sweet voice but it's

definitely not operatic," says Katz. "It was good enough for a

song like 'Just you Wait, Henry Higgins' but many of the songs were just

out of her register. We can't say for sure what the filmmakers were

thinking, but everything points to the fact that she didn't know she

wasn't going to sing the songs. A similar thing happened to Jeremy

Brett, who did not find out until after the movie opened that his songs

were dubbed by a singer named Bill Shirley."

In the end Audrey Hepburn sings only one complete song, "Just You Wait," and

bits and pieces, including some intros, on the actual soundtrack -- yet she

publicly accepted the fact with the grace and warmth for which she remains

idolized today.

"The reconstruction is an homage not

just to the film but to Audrey Hepburn," says Katz. "During the

reconstruction, we were very moved to learn of the birth of Audrey's

grand-daughter. It really choked us up to know that our work was going

to enable her to see her grandmother's performance the way it should be

seen. That's what real restoration is all about."

Katz and Harris hope the restoration will allow all kinds of people to discover

Audrey Hepburn's and Rex Harrison's wondrous performances in their new pristine

condition.

"Even I didn't really know the film

that well when we started, but I've come to love it," says Harris.

"It's just a really great movie, a movie that's more and more fun the

more you see it. It's a great discovery not just for film buffs and for

people who haven't seen it in decades but for young people who have

never seen it before." Katz adds: "I think a lot of people will

find they know the songs, even my kids know the songs, but they don't

know they're from 'My Fair Lady.' They know Audrey Hepburn but they

haven't seen her on the big screen. And the great thing is, now 'My Fair

Lady' can be shown into perpetuity the way she was always meant to look

and sound."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Go:

back

- top

-

back issues

Updated

22-01-25 |

|

|

Artist

Bob Peck's "My Fair Lady" poster, 1964.

Artist

Bob Peck's "My Fair Lady" poster, 1964. "My

Fair Lady" UK full page trade ad from Kinematograph Weekly, December 17,

1964.

"My

Fair Lady" UK full page trade ad from Kinematograph Weekly, December 17,

1964. "My

Fair Lady" playing in Super Panavision 70mm at the Max Linder Panorama,

Paris, France, summer 1990. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev

"My

Fair Lady" playing in Super Panavision 70mm at the Max Linder Panorama,

Paris, France, summer 1990. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev