Restoration of "Spartacus"

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Universal Pictures Press Department, 1991 | Date: 26.07.2009 |

Winner of four Academy Awards, applauded as "monumental," "tremendous,"

"genuinely great" by critics across the country, "Spartacus" has long been

considered one of the screen's great achievements. Winner of four Academy Awards, applauded as "monumental," "tremendous,"

"genuinely great" by critics across the country, "Spartacus" has long been

considered one of the screen's great achievements.Now, more than 30 years after the Kirk Douglas -Stanley Kubrick epic premiered, Universal Pictures has restored the classic motion picture to its original grandeur. This spring, "Spartacus" will be presented as it was meant to be seen: In 70mm and six-track Dolby Sound. As part of the most extensive film restoration in history, five minutes of footage cut from the original release print of "Spartacus" was reinstated, along with the original overture and intermission. A new print, painstakingly reconstructed from decades old negative and color separation prints, has been struck, at a cost of nearly $1 million. Starring Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Jean Simmons, Charles Laughton, Peter Ustinov, John Gavin and Tony Curtis as Antoninus, "Spartacus" premiered in New York and Los Angeles in October, 1960 and went on to win four Academy Awards--for Best Supporting Actor, Art Direction (color), Cinematography (color) and Costume Design (color). The $12 million production, the most expensive movie ever filmed in Hollywood (although its gigantic battle scenes were filmed in Spain), was directed by Stanley Kubrick and filmed in the wide-screen process called Super Technirama 70. "Spartacus" was produced by Edward Lewis, with Douglas serving as executive producer for his Bryna Productions. Some 2,500 employees at Universal Pictures put in more than 250,000 man-hours working on the sets, costumes, greenery, carts, banners and palaces needed to accurately show Imperial Rome. Thousands of extras were recruited for the crowd scenes. For the battle scenes, museums and costume houses in Italy supplied 5,000 uniforms and seven tons of custom-made armor. Although the battle scenes featured thousands of soldiers from the Spanish Army, the battle shouts heard in the film were recorded in East Lansing, Michigan by the Michigan State rooting section. In Hollywood, the set constructed for the School af Gladiators was based on designs 2,000 years old. According to a story af that time, all of Hollywood's 187 stuntmen were hired and "trained in the gladiatorial rituals of combat to the death." "Spartacus" under the direction of then-31-year-old Kubrick, took 167 days to film and utilized approximately 10,500 people. The film was written by Dalton Trumbo, based an Howard Fast's best-selling novel, which, at that time, had been translated into 45 languages and sold more than 3 million copies. In hiring and giving screen credit to Trumbo, who had been unable to find work in the Hollywood community for many years because of the infamous HUAC hearings, Douglas effectively broke the practice of blacklisting. Nearly three decades later, when a print of the film was needed for a ceremony honouring Dauglas and Bryna Productions, it was discovered that no print of acceptable quality could be located. The original running time of the film was 197 minutes, including almost ten minutes of music that consisted of the film's overture, as well as entrance and exit music. Edits made before the film opened cut the running time to 182 minutes, excluding the overture and other music. When "Spartacus" was reissued in 1967 the running time was just 161 minutes. The obvious questions were asked. "Didn't Universal Pictures have a clean print?" "No," was the reply. "The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences?" "Only the short, re-issue version was in their vaults." "UCLA Archives?" "No." Stanley Kubrick's print (the 182 minute version) had been placed on deposit with The Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was considered to be an archive print, and therefore unavailable for loan. The only original 35mm print to be found was in the hands of an avid collector, who had gathered footage from various prints, including material from Europe, and meticulously pieced it together to also form a 182 minute version - that of the standard generic release. The collector offered to make it available. It wasn't the fact that the print was scratched in many sections that caught people's attention, nor that there was a more than occasional splice with abrupt color shifts, where material had been cut together. This was all to be expected from an old print. The unique character of the print run before the honouree was that the majority of the footage that made up the difference between the 1967 re-issue version of and that of the earlier 182 minute version was all sub-titled. |

More

in 70mm reading: Restoration of "Lawrence of Arabia" Restoration of "My Fair Lady" The Reconstruction and Restoration of John Wayne's "The Alamo" Internet link: |

Imperial Bio Copenhagen where restored version of "Spartacus" was shown in 70mm. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Imperial Bio Copenhagen where restored version of "Spartacus" was shown in 70mm. Image by Thomas HauerslevIn October of 1989, Robert A. Harris, who had recently completed the reconstruction and restoration of Sir David Lean's "Lawrence of Arabia" was called in to help. Harris found that, like "Lawrence of Arabia", there seemed to be no surviving print in any format...anywhere in the world. Also, like "Lawrence", there was no readily accessible picture and dialogue continuity which could serve as a guide to precisely what the original version had been. Some reviews mentioned graphic elements of the battle scenes...arms being lopped off--blood spurting from a stump. Film lore had discussed, but few could remember actually seeing the scene in which Tony Curtis is the attempted seductive of Laurence Olivier--what has become known as the "snails and oysters" scene. Nor could people actually remember seeing the blood of the slave Draba (played by Woody Strode) hit Crassus (Olivier) square in the face as Draba's neck is slit by Crassus' knife. Further research confirmed the original 197 minute running time and the 182 minute release version. The search for missing footage, then, would be for some 5-6 minutes of material. Harris contacted Jim Katz, whose years as head of Universal's Classic division and background in production and publicity made him an ideal ally for the project. He and Katz had previously worked together in 1981 on Abel Gance's "Napoleon", which Harris owned jointly with Francis Coppola's Zoetrope Studios. Harris recalls that, as a preliminary budget was being prepared, Steven Spielberg became involved, as he had on "Lawrence". Spielberg suggested that Kubrick be notified, and when the director approved the project, Spielberg called Tom Pollock, Chairman of Universal's Motion Picture Group. Pollock was not only interested, but had the restoration in mind since "Lawrence" was first announced. Harris researched the credits of Robert Lawrence, who had been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Editor for his work on "Spartacus". His credits revealed the editing of films like "55 Days at Peking", "El Cid", the Bond film "Never Say Never Again" and "Fiddler on the Roof." Cutting film for over forty years, he had been broken in as an assistant under directors George Stevens, Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Mann. He quickly agreed to assist in the restoration. After another couple of months of research, the project moved to offices on the Universal lot, directly adjacent to Stage 12, where many of the scenes for "Spartacus" had been shot 30 years earlier. By the time Harris, Katz and Lawrence, along with Mike Hyatt, who had taken a leave of absence from a film optical house to assist on the project, had moved in, Universal's technical people had put together a file of all background material that could be located. To this was added a complete inventory from the vaults - hundreds of pages of computer printouts. Materials were moved from locations around the world to Universal's vaults in Los Angeles. Each individual roll of film is identified, tracked and held at the proper temperature and humidity for each element. Among the "Spartacus" - related papers was the first damage report, the news of which was both good and bad. The records showed that although all of the "B" negative (unused takes), trims and outs, plus all of the original pre-mix sound elements, the effects and dialogue, had been ordered destroyed some 15 years previous, there were still some 2,000 cans of "Spartacus" material available. Every can was to be opened, inspected and checked. The original camera negative arrived from underground storage facilities and several reels were delivered to Universal's negative cutting department. Unlike films today, which are generally photographed on either 35 or 65mm negative and edited sequentially, "Spartacus" was found to be in one of the consummate bastard formats of its day -- Super Technirama 70. Created just after the initial productions in Todd-AO, which used 65mm camera negative ("Oklahoma!", "Around the World in 80 Days") and MGM's Camera 65 process ("Ben Hur", "Raintree Country"), Super Technirama 70 was a good idea. Technirama was based on Paramount's system -- VistaVision. It gave access to a larger negative area, while still using normal 35mm film. The difference being that the film was transported horizontally through the camera at 180 feet per minute, giving a frame twice the area of the normal 35mm negative. The quality was superb. Technirama used basically the same large, bulky camera system a VistaVision -- but with one change. A special lens was used to optically squeeze the image by 150%. This meant that when unsqueezed, the resulting image would perfectly fit a 70mm frame. If the filmmakers were desirous of having a standard 35mm release, the image would simply be squeezed a bit more, yielding a standard Panavision 2.35:1 aspect ratio for normal wide screen 35mm projection -but with amazing results. |

|

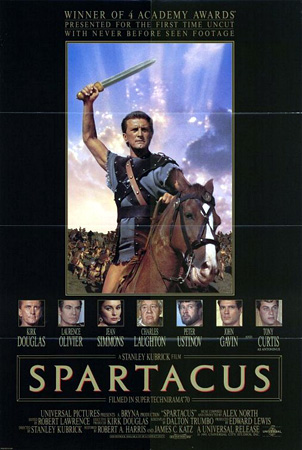

One sheet re-release poster One sheet re-release posterThere were two problems with the original "Spartacus" negative. First, it appeared to have been re-cut not once, but twice, and contained none of the material from either the preview or pre-censor versions. Second, it had a sickening blueish/lavender cast -- sickening, not because the color itself was objectionable, but because to a negative, this was the pallor of death. Still, it was worth a test. The results were less than presentable. Printed in its original Technirama horizontal format, the image was sharp, but lacking contrast and the color...The shadows had turned blue. There was no black reproduced whatsoever, and the facial highlights were a bright yellow. Although some 35mm reduction elements had been produced over the years, the ultimate materials protecting "Spartacus" were the black and white protection separation masters ("seps"). Produced for most important films--but not all--they were created by exposing black and white "fine grain" stock through different filters--yellow, cyan and magenta. In this way, all of the color information on the original negative could be preserved on a non-fading film element (black and white stock). Three black and white prints would be made--one through each filter. These prints could then be recombined, when exposed through like filters to produce a hopefully usable duplicate negative of commercial quality. At least that is the way the system is supposed to work. Black and white separations were originally meant to backup the negative in case a shot or two were destroyed during printing. The reproduction of an entire film through its black and white elements was something that most studios would shy away from at any cost. But Universal gave the go-ahead. A final budget was approved. The film would be restored. Meanwhile, sound elements were being tested and prepared for dubbing in Universal's sound department. The original mix for "Spartacus" had been done in 6-track discreet. This means that different sound would come from each of the five speakers behind the huge screens used in theatres in the early '60s. This was well before the start of the age of the "plexes." The sixth channel was for effects. The original six-track magnetic master had survived well in Universal's vaults. The quality was superb. Unlike today's mixes, in which most dialogue is recorded in the center channel of a stereo mix, the dialogue in "Spartacus" moves with the character from the far left to far right across the screen. When a shot changes angle, the sound reverses with the picture. The master, with no sync marks or beeps to align with the picture, was from the generic version--182 minutes. While cutting the material together, the missing track elements had to be kept in mind. It appeared that none of the missing track had survived and it would have to be produced from scratch. There was music, but no effects or dialogue. Sound editors Gib Jatte and Mark Gordon joined the project. New effects had to be created. In some cases, such as the "snails and oysters" scene, for which new dialogue had to be recorded, the existing tracks for fragments of the scene in the generic version of the film would not be used, as music would not fit. While the picture was being cut, Jim Katz began to arrange for the completion of the "Snails and Oysters" scene. He brought Tony Curtis to Los Angeles to record his lines, as found in Kirk Douglas' original copy of the script. Harris contacted Anne V. Coates, editor of "Lawrence", and asked if she would be kind enough to contact Joan Plowright, the widow of Sir Laurence Olivier. As a courtesy, no one wanted to have another actor attempt to reproduce her late husband's voice without her approval...and if she did approve, was there a suggestion as to talent? Anne reported back that Joan had suggested Anthony Hopkins, but didn't know if he would do it. Katz located Hopkins' agent in London, who at first found the request unusual, to say the least. Jim was told that he honestly didn't know how to react, but that he would contact Mr. Hopkins and get back. Not long after, he called back, amused with a likewise amused Anthony Hopkins conferenced into the call. "What was involved?", asked Hopkins. Katz explained. "Would he consider doing it?", queried Katz. "If it's got to be done, and Joan suggested she'd like me to do it...an honor," replied Hopkins. Picture tests began with the recombining of the separations in a Technirama format test. The color looked promising, even though not yet timed out (color corrected). Various optical houses and laboratories were checked for their availability and capability of handling the original Technirama format. The original lab which produced the seps was incapable of producing a negative from them for various technical reasons. Another large lab was wary. Because of the delicate nature af the work and the speed of their printer, it would take almost a thousand hours to produce the negative, with shifts running through the day and night. |

|

Imperial Bio Copenhagen where restored version of "Spartacus" was shown in 70mm. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Imperial Bio Copenhagen where restored version of "Spartacus" was shown in 70mm. Image by Thomas HauerslevWorking with project production executive, Gary Bell, the staff decided to try a small, privately owned "boutique" lab, which had been producing dupe negatives-from seps and showed perfect examples of their work. This was to be the first time that anyone had ever attempted to re-combine the separations of a Technirama negative and transfer it to 65mm dupe negative at the same time. It entailed a combination of a format change with an optical process for which no lens was readily available. Panavision, which had supplied lenses for the original photography, attempted to devise options, but their creations would not work within the parameters of the system at the optical house. There were no other lenses to be found for this 30-year-old format. Bell called Deluxe, the lab that would be doing the processing and printing. They had a lens, but it had been made for their own system years before, and would not be usable with anyone else's printer. They offered to loan it to the project for testing. The lens gave a sharp center, which quickly fell oft to non-focus as it approached the edges of the film. Additional optics were produced and tested to attempt to bend the light as it came out of Deluxe's lens. Months of testing, trial and error, went by, as test by test the focus became better, the image size more accurate. There would be no sense of wasting the time of Stanley Kubrick, a known perfectionist, with footage in which the edges were dark and out of focus. He waited patiently in London. While the lens tests continued, Katz went to London to oversee the recording of Hopkins' lines for the "Snails & Oysters" sequence. Kubrick sent a fax with instructions as to how the scene should be played. When the dialogue arrived back in Los Angeles, it was combined with that of Tony Curtis and a scene was reborn. Two professionals, independent of one another, had spoken their lines on separate continents--and the scene worked. The actual dubbing of the film took place in the third week of October, 1990. Jaffe and Gordon had done their job. Everything fit. The new tracks had been built and mixed and worked perfectly combined with their 30-year-old counterparts. But no lens was yet ready and more tests were made. With everything else completed, Harris returned to his East Coast office. The office at Universal would keep things working, with material shipped to Harris daily. By mid-November, the tests were getting close. The light was spread evenly across the image, sharpness was getting very close, but still more tests would be made. Finally, a new lens was produced and the restoration process was completed. Through the commitment of Universal and the diligence and work of many people, a motion picture had been saved. "Spartacus" could, for the first time, be seen as it was meant to be by its creators. UNIVERSAL PICTURES Presents A BRYNA PRODUCTION. KIRK DOUGLAS, LAURENCE OLIVIER, JEAN SIMMONS, CHARLES LAUGHTON, PETER USTINOV, JOHN GAVIN and TONY CURTIS as Antonius, "SPARTACUS", Music Composed and Conducted by ALEX NORTH, Executive Producer KIRK DOUGLAS. Screenplay by DALTON TRUMBO. Produced by EDWARD LEWIS. Directed by STANLEY KUBRICK. RESTORED BY ROBERT A. HARRIS AND JAMES C. KATZ, A UNIVERSAL RELEASE. |

|

The Restoration |

|

|

Reconstructed and restored by Robert A. Harris.

Reconstruction and restoration produced by James C. Katz.

Editorial consultant Robert Lawrence.

65mm preservation composite negative produced by RGB Optical, Inc.

Manager of optical operations Paul Rutan, Jr.

Camera operations John Rupkalvis,

Robert Fortenberry, Jr.

Negative cutting Brian Ralph.

Production assistant Mike Hyatt.

Timer David Orr.

Sound editing by Sound Choice.

Sound effects editors Gibb Jaffe, Mark Gordon.

Supervising re-recording mixer Rick Alexander.

Re-recording mixers Joel Fein,

James Bolt.

Foley mixer Karin Roulo.

Foley artist Diane Marshall.

Dolby consultant David Gray.

Re-recorded at Universal Studios Sound Department.

Dolby Laboratories SR Card.

70mm prints by Deluxe Laboratorles.

Special thanks to

Anthony Hopkins,

University of Wisconsin Center

For film & Theater Research

Kirk Douglas collection.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Technicolor.

Filmed in Super Technirama. Lenses by Panavision. |

|

The Credits |

|

|

Bryna Productions, Inc.

Presents

Kirk Douglas (Spartacus),

Laurence Olivier (Crassus),

Jean Simmons (Varinia),

Charles Laughton (Gracchus),

Peter Ustinov (Batiatus),

John Gavin (Julius Caesar) "Spartacus" Co-starring Nina Foch, Herbert Lom, John Ireland, John Dall, Charles McGraw. With Joanna Barnes, Harold J. Stone, Woody Strode, Peter Brocco, Paul Lambert, Robert J. Wilke, Nicholas Dennis, John Hoyt, Frederic Worlock and Co-starring Tony Curtis as Antoninus Directed by Stanley Kubrick. Produced by Edward Lewis. Executive producer Kirk Douglas. Screenplay by Dalton Trumbo. Based on the novel by Howard Fast. The credits Director of photography Russell Metty, A.C.S. Production designer Alexander Golitzen. Art director Eric Orbom. Set decorations Russell A. Gausman. Julia Heron. Main titles and design consultant Saul Bass. Sound Waldon O. Watson, Joe Lapis, Murray Spivack, Ronald Pierce. Historical and technical advisor Vittorio Nino Novarese. Unit production manager Norman Deming. Additional scenes photographed by Clifford Stine, A.S.C. Production aide Stan Margulies. Wardrobe by Peruzzi. Miss Simmons' costumes Bill Thomas. Costumes by Valles. Film editor Robert Lawrence. Assistants to the film editor Robert Schulte, Fred Chulack. Score co-conducted by Joseph Gershenson. Music editor Arnold Schwarzwald. Make-up Bud Westmore. Hair stylist Larry Germain. Assistant director Marshall Green. Music composed and conducted by Alex North. |

Universal Press Department Universali Studios Universal City California 91608 USA Phone: (818) 777-1293 |

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|