Mikael Salomon and "Far and Away" |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Interviewed & Transcribed by: Thomas Hauerslev, Thursday, 24. January 2024, Copenhagen, Denmark. Edited, and clarified from the text by: Paul Rayton, in70mm.com, Hollywood, and Mikael Salomon, Denmark | Date: 20.08.2024 |

"I

still remember the very first shot I did. It was an instructional film shot

in Malmø [Sweden] about how to put tar paper on a roof for a roofing paper

company" Mikael Salomon. Photo credit: Thomas Hauerslev "I

still remember the very first shot I did. It was an instructional film shot

in Malmø [Sweden] about how to put tar paper on a roof for a roofing paper

company" Mikael Salomon. Photo credit: Thomas Hauerslev

|

More in 70mm reading: Gallery: Mikael Salomon and "Far and Away" Mikael Salomon's introduction to "Far and Away" "Far and Away" Production Notes Imagine Films Entertainment Presents "Far And Away" The Irish Story: On the trail of "Ryan's Daughter" & "Far and Away" “Far and Away”: The North American 70mm Engagements “The Abyss”: The North American 70mm Engagements “Backdraft”: The North American 70mm Engagements “Arachnophobia”: The North American 70mm Engagements “Always”: The North American 70mm Engagements The Importance of Panavision Motion pictures photographed in Super Panavision 70 & Panavision System 65 Panavison Large Format Motion Picture Systems in70mm.com's Library Presented on the big screen in 7OMM Peripheral Vision, Scopes, Dimensions and Panoramas |

Trade

advert from Laterna Film A/S where Mikael began his career. Trade

advert from Laterna Film A/S where Mikael began his career.This is really a long story, but in short I went to a documentary company called Laterna Film. I had been to a lot of other companies and nobody had any need or didn't want me, and who knows, but this place, it was a different story. The boss there, his name was Mogens Skot-Hansen, he said “No, sorry, Mr. Salomon”, (everybody was very formal in those days) “I'm afraid we don't have any positions”. Then his assistant called out, “Mr. Skot-Hansen, you know our messenger boy is going on summer vacation for two weeks”, and I spoke up and said, “I'll take it!” So I became a messenger boy at Laterna Film. Six weeks later, I shot my first shot [smiles]. It was fast. I knew everything about cinematography at the time. In theory, of course. I had actually never had my hands on a real film camera! I still remember the very first shot I did. It was an instructional film shot in Malmø [Sweden] about how to put tar paper on a roof for a roofing paper company, and I still remember that shot. In those days the pan heads, or the panorama heads, they were all manual in the sense there was no friction or gyros or anything like that. It was loose, and I was shaking all over, trying to do that first shot, but it worked out all right and I started shooting more and more for the company. Then I said [to myself] “I’ve got to learn some more about this”, so soon I became a focus puller for a cameraman by the name of Rolf Rønne. I worked with him for a year and half or something like that, while he shot a feature film. Then I was asked to do a short film, a dramatic piece called … I can't remember the exact title. [muses out loud: What was it called, anyway? ["Miss Julie 1970" / "Frøken Julie 1970" (1969)]. The director was Kirsten Stenbæk, a Danish director and she was also an artist. Painting, and all kinds of multimedia. I shot it for her in black and white, and people liked it. Kirsten Stenbæk and her husband, Bent Grasten, had written a movie called “The Dreamers” [1967]; in Danish it was called “Fantasterne”. I think I was 21 at the time, and the studio said “You have to have a cameraman”, and she said “I want Mikael to do it. He just did my short film” and the studio said “No, no, no way!” In those days a cameraman, you know, was a very noble artist. But she said “OK, then I won't do it.” So she hung in there, and they relented, and that was my first feature. “Fantasterne”, shot in black and white, and I realized only recently that the first four directors I worked for were all women. Which in those days was very common around here. Nobody thought about it. They were Alice O'Fredericks and Annelise Reenberg, Annelise Hovmand and Astrid Henning Jensen, and I had a great time. For Alice O'Fredericks I shot a Morten Korch film called “Brødrene på Uglegården” [1967] starring Ib Mossin. Later I did films with Dirch Passer, Paul Reichardt, Preben Kaas, Jørgen Ryg, Lily Broberg, Bodil Udsen and Ove Sprogøe. All of whom have sadly now passed away. It was such a great learning curve for me because I just rolled film through the camera all year long. Sometimes I would shoot five features in a year because the production schedules were very short! THa: How was the education? I mean, it sounds to me like you were self-educated or self-taught? Mikael: Very much so, yes, and I mean, of course, when I worked as a camera assistant for Rolf and a couple of other guys, I had a short stint as a camera assistant for another cameraman by the name of Henning Bendtsen. I don't know if you know of him … THa: He photographed [Carl T.H.] Dreyer’s movies. Mikael: That's correct, yes he did, and he was great. "Brødrene på Uglegården" was my second feature and the first colour picture I shot. The studio asked Henning “Can you keep an eye out and see if he knows what he's doing?” And Henning came to me. “I know you know what you're doing, so I know you will be fine.” And it went well. In those days, you didn't watch your dailies in color. You watched them in black and white because it was too expensive to print dailies in color. So sometimes, if you were lucky, you’d get a strip with different timings of a scene. And that was it. It would have been so nice to see the whole thing in color, but that was a luxury you couldn't even imagine. That was [only in] the United States. THa: Who in those days, were your mentors, your teachers, when you were only 20? Mikael: Well, I was learning on the job. When I speak to film school students I tell them, “Just say yes to everything, except porn, because it will all give you experience. If you shoot porn, then you land where you may not come back. It pays well, but it sucks.” THa: You tried it? Mikael: Yes, I tried it, but that was more like an official, or educational, porn film, in the sense that it was shot in 35mm for Saga Studio, and there were two US psychologists called Eberhard and Phyllis Kronhausen. And it was sort of like a 60-minute class study, where they were saying “Why are these people doing it in the first place?” And I mean, it was easily answered, MONEY! [laughing]. We had a full film crew with three cameras, and 35mm which was very unusual, but they had the money for it. But from experience, I can give this advice: Don't do it. But shoot industrials, shoot anything else, and you learn how your film emulsion responds. In those days the films' sensitivities were so low. We were shooting on emulsions rated at 16 ASA and 25 ASA. It was always a problem getting enough light. Especially in winter, because then you could only shoot between 10:00 and 14:00 (2 pm) maybe, and then the daylight would be gone. So that made it very difficult to schedule a feature with exteriors. You have to make certain you can go and shoot interiors for the rest of the day. You can't just take the rest of the day off. THa: I think "Lawrence of Arabia" was filmed on 12 ASA throughout the movie, but they had enough light, of course. Mikael: Yes, they had the sun. They wouldn't have shot interiors at 12 ASA, probably at 25 because when you shoot outside, you use something called an 85 (orange) filter, and when you remove that, you get an extra ¾ of a stop. I shot a lot of Kodachrome and Ektachrome in those days. Those were reversal films, and that really taught you how to expose properly because there was zero leeway. You had to be spot on. But the colours were much better than negative film in those days. But with negative, you had a latitude – to screw up [laughing]. THa: Yes, plus or minus one or two stops. Mikael: Yeah, well, it depends on where your pain threshold was, you know. |

Dear Thomas, This is far and away the best interview you have done. I have talked to many DPs, including Robbie Ryan who used a VistaVision camera in "Poor Things", Greig Fraser on "Dune", Rob Hardy on "Civil War" and Haris Zambarloukos on "A Haunting in Venice". Mikael is the most interesting and that comes across very powerfully in this interview. This is far and away more in depth and comprehensive than any interview I have read in American Cinematographer, British Cinematographer, Cinematography World and Cinema Technology. It is in a class of its own. That said, "The Hateful Eight" was a deeply uncomfortable experience for many. it is one of the most claustrophobic atmospheres ever to be created on film, given the immersive nature of the Ultra Panavision 70 print, especially on the Cinerama screen. Those people escaped a snow bound hell only find themselves in an even worse hell. Hell as the French philosopher Satre once observed is other people. Here endeth the heavy bit. A great piece of work, well done. Cheers, Mark Lyndon, London, UK |

Title

card for “Cop”/"Strømer" with caption: "Photographed in Panavision by Mikael

Salomon". From the film Title

card for “Cop”/"Strømer" with caption: "Photographed in Panavision by Mikael

Salomon". From the filmTHa: I did not see a lot of Danish films from the 1970s, but it seems to me that you were among the pioneers of using anamorphic lenses in Denmark. Can you talk about that a little bit? Mikael: Most people say that “Cop” [“Strømer”, Dir. Anders Refn, 1976] was the first anamorphic film shot [in Denmark. However, that is not correct. “Hearts of Trumph” ["Hjerter er Trumf", Lars Brydesen, 1976], was the first with Panavision anamorphics. We had to go to London [Samuelson Film Service] and get one camera and two lenses. The whole movie was shot with those two lenses. That's all we could afford. But before that, I worked on a short film that Rolf Rønne shot. I think Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt was the director, which was called “Sommerkrig” [1965]. We shot that with the Swedish system called Agascope. Have you heard about that? I've also shot on something called ARRIscope. Those lenses were all terrible [laughing]. I also shot a movie called “Flying Devils” ["De Flyvende Djævle", Anders Refn, 1985] in anamorphic [Winner, Danish Academy award Robert for best Cinematography]. I think those were Kowa lenses from Japan. Today if you open a modern lens up, and it is still crisp, sharp, with beautiful soft focus [bokeh] in the background, however, in those days, if you opened wide up on an anamorphic lens, you ended up with blurry focus everywhere [laughs]. You just couldn't do it. You had to stop down to at least to f:4 or 4.5 to get a decent resolution. So it wasn't great. That was when, eventually, Super 16 came along. Rune Ericsson, a Swedish cameraman, invented it, and I never will forgive him for it. It's the worst system in the world because the cameras were not built for Super 16. You would be using the area intended for the soundtrack area to add additional image area. A brilliant concept, but the cameras were not built for that format. They removed some rollers to accomplish that and what have you, but you were always getting scratches. It was so infuriating. But it did resolve in a slightly better resolution than normal 16mm, and it had the widescreen format 1,66:1. THa: What is so pleasing for you about anamorphic and the wide 2,35 or 2,39:1 format? Mikael: I’ve always said 2,35, because, I don't know, some people say 2,40:1, I don't know. THa: But they changed it in 1969 or something? [* see technical note – ed.] Mikael: But it's not really changed from the camera aspect of things. I mean, the good thing about anamorphic is you actually squeeze more out of the film, because it ends up being a square image area [almost – ed.], and you have a lot more image [space]. I think it’s effectively about 40% more stock [compared to 1,85;1, ed]. When you shot 1,85 so-called “widescreen”, you throw away a lot of image area. A huge, thick frame line. The good thing about Techniscope, and eventually Super 35, is that you only pull down two perfs on Techniscope, or pull down 3 perfs on Super 35. That gives you more image area, obviously, as you could see in “The Abyss”, shot in Super 35. Jim Cameron wanted to shoot anamorphic under water and I told him, “Listen, it’s just not happening.” The problem is, how do you light under water? That had never been done. Jim had never thought about it, either, at that point. So I said [to Jim] “We have to use spherical lenses, normal lenses, and not anamorphics for this. I did a movie in Denmark in Techniscope ["Threesome" (1970)]. Maybe we can figure something out.” So I went to Clairmont Camera, in L.A. Denny agreed to build a camera that would pull down three [perfs], and where we could expose over the entire full aperture area of the film [including area normally reserved for the optical soundtrack, ed] The advantage of anamorphic is much better quality, of course, than Super 35, because you can use the whole image known as the Academy frame. That's the old 35mm [format] 1,37:1. But eventually the lenses got better. In the old days when they shot all these films in scope on stages and sets, they had more lights than we ever had. We never had those big lights in Denmark. We wouldn't be able to afford it. • Go to The Making of "Dance Craze" in Super 35 • Go to Joe Dunton Q/A |

*) Technical note: The physical film frame did not really change the aspect ratio

of the photographed camera image, but rather it modified the definition of the

projected aspect ratio, which was modified from the long-time ~2.35:1 to the new

~2.39:1 in 1971, and was done to minimize the “flashing” of the splice lines at

the point of each cut of the cut negative roll. For a fuller and more precise discussion of the whole 2.35-2.39-2.40 evolution, see the section “Aspect Ratio”, about halfway down the page, at Wikipedia |

Opening

shot of "Far & Away" was photographed here. Seen from the Clogher Head location in Dunquin, Ireland. The village set was built on the

field in the foreground, with a clear view to the school house from "Ryan's

Daughter" in the far background. Photo credit: Thomas Hauerslev,

July 2024 Opening

shot of "Far & Away" was photographed here. Seen from the Clogher Head location in Dunquin, Ireland. The village set was built on the

field in the foreground, with a clear view to the school house from "Ryan's

Daughter" in the far background. Photo credit: Thomas Hauerslev,

July 2024THa: Tell me about the beginning of “Far and Away” “Far and Away” got started when we were doing “Backdraft”. One day [Ron] said, “I want to do this little film called “The Irish Story”, and we'll just go to Ireland and do it. You bring a small Danish crew and we'll shoot with you for almost nothing.” Then it all got to be a big deal when Tom Cruise came on board for the project, and I told them I had always wanted to shoot 70. The only reason I got to shoot “Far and Away” in 70mm was because we -- this was before the digital soundtracks -- Ron, Brian and myself, convinced Universal Pictures they could have full 6-track magnetic stereophonic sound rather than optical sound, and they liked that idea. Universal Pictures was not convinced. They’d put it in the budget and then cut it out again. They were looking to save some money so, the 65 photography would be cut out once again. I had to say, “Ron, let's do it.” “OK. We'll do, we'll do it.”, he replied. THa: What was your inspiration? How did you get the idea to shoot that particular film in 65mm? Mikael: Just the subject matter I mean. The format has been abused in my opinion. I think "The Hateful Eight" by Quentin Tarantino, he shot it with no justification to shoot in 70. It's all shot like a theatre play. Big screen. A lot of people talking. I admire the cameraman, Bob Richardson. He's great cameraman – the best. The beginning was beautiful, but all those scenes inside that place ... was it an Inn or something? I think they also created film magazines for the cameras that were twice as big, so they could shoot long, what a waste, I mean, what a waste! It's a TV movie in my opinion. So anyway … THa: How would you describe the creative process of “Far and Away”, I mean the decision about 65mm camera system, lenses and the look of the film? How do you decide? Is that a collaboration between the director and you? Mikael: I believe that the look of a film in most instances will be a product of the people you bring together. Obviously, you sit down and discuss a little bit, but also I find that many times the Costume Supervisor, the Production Designer, etc., we're all working on the same project, but at one point it all comes together and becomes “the look.” You can, of course, at the start, announce we'll be shooting this in seventy, and everybody says, “Oh God, we really must be on top of our form.” But as I told you before, the process was simply curiosity. I mean, I'd like to play with all the toys, and why not? My idol was always Freddie Young, who ended up being a friend. I went to his 90th birthday at Shepperton Studios. He was the one who shot “Lawrence of Arabia” and "Ryan's Daughter". That was the one I was hoping to emulate in the very first shot in “Far and Away”. Now there’s an interesting shot. We actually lost an entire helicopter on that one, too! We were to start over the ocean and then come back toward land. And the interesting trivia piece about it is, we had built a little location village as our set out there [on Clogher Head, ed], and I said, “Ron, we’ve got to get that house in the shot. That's the schoolhouse from ‘Ryan's Daughter’”. I had that scripted into the shot, but what happened was, it was bad weather, and it was really cold. Usually I would operate, but the guy who had made the helicopter mount for the camera, he wanted to operate it himself this time. “OK, you can operate it, but as long as the shot is like this, and come back". In comes the title card with … I think Tom Cruise is on it, or something like that... |

|

Mikael

Salomon behind the Panavision System 65 camera with Tom Cruise in front. Picture courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collection Mikael

Salomon behind the Panavision System 65 camera with Tom Cruise in front. Picture courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collectionThey did the first take. We had another helicopter to fly with them, but behind them. Just for safety, because the weather was really nasty. We were standing on kind of a cliff. We couldn't see the ocean right below the edge. It's almost like in the Channel Islands, with a very steep drop off. The shot starts low over the water, and comes back toward land. You've seen the shot, right? They came back from the first run, and showed me [the footage] on a small monitor, which was the only thing we had at the time, and took a look at the video. I told Ron we should do one more take on the shot, and Ron agreed. “Yeah, let's do one more”. Now, a little more technical detail: We were using a SpaceCam stabilizer and a VistaVision camera for these shots. We originally planned to create a platform that would carry our 65mm camera, but it wasn’t ready. So it was a VistaVision camera we were using. The SpaceCam stabilizer can carry a VistaVision camera. I'm sure you know, that one is a 35mm camera in which the film runs horizontally, and it's spherical lenses also [smiling]. The camera operator said, “We’ve got plenty of film in [the magazine] for one more take. Let’s just go.” I said to him, “Will you please do me a favour: just reload, please?” So they put on a second magazine, while kind of rolling their eyes a bit. And then the helicopters went out again. The helicopter pilot was a friend of mine. I've done a ton of commercials with him. His name was Robert 'Bobby Z' Zajonc, and I was on the radio with him on a walkie. They would have to do their thing out there over the water, and then we would see them rise up into view [from below the cliff line – ed.] … but when they didn't come up. I said “Bob, what's going on?” - “We're going down!” - "What do you mean, Bobby?” So we ran, Ron and I -- we were the only ones standing outside because it was so freaking cold! We ran out, and just as we got to the edge of the cliff, we see the helicopter, on the water, and it’s breaking in two and starting to sink. And that was the helicopter with the camera and the operator, not the “safety” companion helicopter! That was the one with two people in there. It took us like half an hour to get out to him, and he was only saved because the cupola of the helicopter cracked, and the seats are floaters, they'll float as an emergency cushion. They came loose and pushed Bobby, up to the surface. We could see him out there in the water. We climbed over some huge rocks, where the water and the ocean was so bad. I mean, we got down there to water level, but started to climb across these rocks, out to where they were, close to the rocks. It was so slick. I was sure we were going to break our legs just because of slipping off them. The camera operator came out of the side door just as they landed on the water, and then he managed to get free. They threw a rope down to him from the safety helicopter and actually pulled him over to the shore with the helicopter rope. We finally got hold of Bobby, and he was kind of blue and was bleeding from the back of his head. This was bad, but it ended OK, and we got him to safety. End of story: that first magazine contained the only take ever of that shot. That's the one that got downloaded. That's the one that's in the movie. We never got another. Ron did a photo of me pulling at Bobby Z there, out there in the water. And I'm sitting there giving him a nasty look. I said like “Why aren't you helping me?” It took a while. We formed a human chain, so we could carry him in on a gurney, a stretcher. They both went to the hospital, but they survived. So that was good. But the camera and everything were lost. So that was a nice VistaVision cameras that went down. |

|

Example

of the use of the "Swing and Tilt" lens in "Far and Away". Cruise in far

background in focus, while Kidman is in foreground - also in focus. "Far and

Away", Universal Pictures, 1992. Frame grab courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collection Example

of the use of the "Swing and Tilt" lens in "Far and Away". Cruise in far

background in focus, while Kidman is in foreground - also in focus. "Far and

Away", Universal Pictures, 1992. Frame grab courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collectionTHa: “Far and Away“ distinguished itself by being the first film with Panavision’s two new System 65 cameras. Were you involved in the development of them? Mikael: No, not the cameras. I had a dialogue with Panavision when I had heard they'd made those cameras, but I had nothing to do with the development. I knew that ARRI had two or three Arriflex 65mm cameras. Panavision said they'll let us have the cameras for the same price of 35mm. And the more important thing is, Kodak said "We will sell you the 65mm film for the price 35". That was when Universal started coming around, “OK, maybe…”, and I had to promise not to use any more lights than I would on a 35mm shoot [my fingers discretely crossed behind my back, laughing]. Actually, I don't think I did use more light, but that led to, frankly my developing of something called the “swing and tilt” lens. I thought to myself, “Why can't we build something like view camera lenses but for cine cameras? We made some tests, and Tom [Cruise] was all excited. Panavision agreed to make these lenses, like three or four of them for the 70mm cameras, and they said “OK, Mikael, we are only doing this because of you because we've had a great relationship, blah, blah blah. It's going cost us a lot of money”. Once they were done, though, they went ahead and built, I think, thousands of them, because everybody wanted to use that system, mainly for commercial, but also for dramatic purposes. Because it's great, the principle is that if you have … here's the camera [illustrates on table], right, and here's your focus plane. If you tweak this a little bit, the focus plane is no longer perpendicular to the film plane. That means that this person in the back can be in focus, and this person in the front can be in focus when you tweak it like that. The principle was long known in stills photography, from old view cameras. That's what I was hoping for, and I thought 35mm is probably not possible because everything is so small. With 70, though, everything is a little bigger, so you can get hold of the lens. It's small, it's very small. Micro screws you know. So, they did it, and it worked. • Go to "Far and Away" Production Notes • Go to Imagine Films Entertainment Presents "Far And Away" |

|

"Far

& Away" on location in Montana. Tom

Cruise, Ron Howard, Mikael Salomon, and Ian Fox (First Assistant Cameraman) with Panavision's

System 65 camera. Picture courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collection "Far

& Away" on location in Montana. Tom

Cruise, Ron Howard, Mikael Salomon, and Ian Fox (First Assistant Cameraman) with Panavision's

System 65 camera. Picture courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collectionTHa: Talk a little bit about other tricks in “Far and Away” Mikael: Tom is dying in one scene, and it involves a crane shot. The camera goes up, and returns very fast. It is big Titan crane and a Louma crane on top of each other with the big camera. The problem was, the shot was too long, and Tom had dialogue. In order to make the crane move fast, I had to undercrank to 8 fps, but I had to get there gradually because I needed to start at 24 frames per second because the scene had dialogue, then slow the camera [to speed up the motion on screen.] So I had to shoot at 8 frames going up and then he kind of comes back to life and we come down down. So we're still staying at 8 frames, and then, just before we go down, we go to 24 again. That was fairly easy. The big problem is that exposure changes when you change the speed. So when you go 8 frames you effectively get two more stops of light. You can't get away with that without adjusting the exposure. So, I had them synch the variable shutter on the Panavision camera, with the frame rate. And that was all a little clunky. While we slow it down to 8 [fps], you have to stop down two stops. When I come back from 8 to 24 it has to be back to whatever the stop it was at the beginning.” They actually did that. And that's in that shot. It's under cranked all the way through those crane moves but when he talks, it's back to 24 and you can't see the difference in exposure. That was all done manually. Today, however, you would do such tricks digitally. So it's much easier now, which is a pity in a way. THa: I once asked Ken Annakin if it was difficult to work with the Todd-AO 65mm camera and he replied, that he was brought up with three strip Technicolor, so using Todd-AO was very easy. How was Panavision’s System 65? Was it easy to use? Mikael: It's very easy to use. Basically it's the same thing but its bigger, bulkier and we interspersed shots with the ARRI 765 camera -- even though they were not suitable for everything -- and you had to use the Hasselblad lenses for them, but they could go 120 frames which Panavision could not. And we needed that for the horse race. There’s the shot showing Kidman on a horse, which required slowed motion at 120 frames. And I think that those magazines were only 400 feet or something like that, really a short time for a shot at 120fps! We also used an older Panavision 65mm camera that wasn't blimped. The two System 65, they were blimped. We had some Steadicam shots with that 65mm "wild" camera, as it is called, where we had to use two Steadicam arms to support it. It was very heavy, and the poor operator Greg Lundsgaard was suffering. But there's a long walk and talk sequence on a ship and over obstacles and we couldn't put the big blimped camera on Steadicam. THa: Did you consult or participate with the lab work for “Far and Away”? Mikael: For colour grading, yes, absolutely. There really weren't that many visual effects, but yeah, of course I did. THa: How does that take place? I mean, do they say on Wednesday we will develop all these rolls of film. Can you come and have a look, please? Mikael: No, no what happens is they do it on a daily basis. At the end of each day, like on all almost all movie productions, you send your film back to Los Angeles, or wherever the lab is. In this case we shot in London, also in Ireland, and we had to send it to ARRI’s lab in Munich [Germany]. • Go to Introduction to "Far and Away" • Go to “Far and Away”: The 70mm Engagements |

|

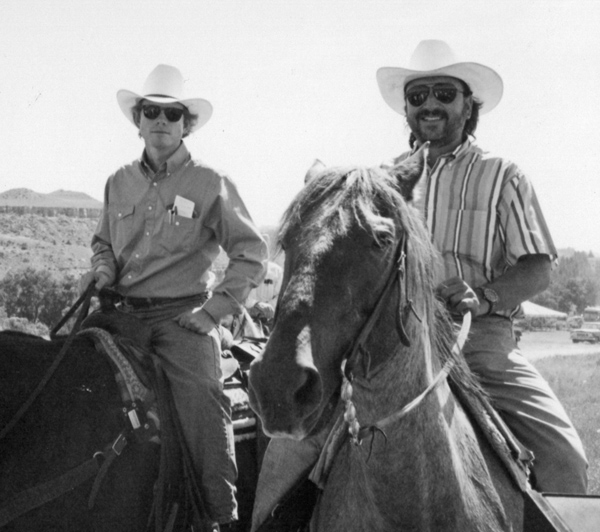

"Far

& Away" on location in Montana. Ron Howard and Mikael Salomon on horseback.

Picture courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collection "Far

& Away" on location in Montana. Ron Howard and Mikael Salomon on horseback.

Picture courtesy Mikael Salomon's

collectionTHa: One question that has intrigued me for a long time: “Far and Away” in 1991 was the first major motion picture shot in 65mm since “Ryan's Daughter” & "Song of Norway" (1970), and “The Last Valley” (1971) [Not including "Tron" (1982) and "Brainstorm" (1983)]. What was the reaction from the industry when you announced you went into production in 65mm? Mikael: People were very positive, obviously. They thought it was great. Again, it was like when CinemaScope and then 3D came out [1953]. Everybody thought it was going to make people come back to the theatres. You have to admit, it doesn't matter what format it is shot in. If it's a good story, that'll get people in. That has always been the case and still is, but there's no denying that “Lawrence of Arabia” could never have had the had impact, had it not been shot in 65. It's such an enormous difference, I think. Have you seen the digital version? I mean, it's beautiful. I was at the premiere in Los Angeles at Sony Studios, and you can tell the negative is big, even though it's digital in projection. It's just beautiful. Rock steady. Then we say rock steady today -- digital is, of course, rock steady. I just saw one of the Academy movies, “The Holdovers” where they made fun of that. A little bit of unsteadiness in the beginning, to make it look like an “old movie” presentation. As I said to my girlfriend, "that is for connoisseurs". THa: “Far and Away” was your last film as a DP (Director of Photography), wasn't it? Mikael: It was, sort of. I actually started doing another one and then I left. I said OK, I should be doing something else. THa: Why did you decide to become a director? Mikael: Simply because I thought I wanted to do something else. Most people said “Are your crazy quitting? You're at the top of your game?”. So yeah, I know. But I didn't want to get bored, and I felt I was doing the same thing over and over again. I had shot a lot of movies. I had played with the big toys, and then I had a not-so-good experience. Up to that point, all my experiences had been great. Then the last movie was “Scent of a Woman”, and it was not a good experience. I said “OK, I’m going to do something else now.” People said “You can do it”, and the first thing I got to do was a TV pilot called “Space Rangers”. It was alright, but nothing big. But then I had read a script that Kathleen Kennedy had showed me earlier. It was called “A Far off Place” (1993), and I told her I really like that. She said, “Yeah, but this French director is doing it and blah, blah, blah. You should come and do ‘Alive’ with us on the mountain”. I turned that one down, even though Frank Marshall called me. We had done one together -- I did “Arachnophobia” (1990) for him -- and he said “You should come to Canada and work on ‘Alive’”. I said, “I've had enough snow in my life in Denmark, I don't need any more!” He said, “But you've done sand, you've done water, you've done everything”. Yeah, including snow. But I mean, we're friendly, so I could decline without getting blacklisted. And, had I actually done it, I wouldn't have been able to take over “A Far off Place” as a director. So, I got call from Steven Spielberg's office, and was told, “Come and have a look at some dailies”. They wanted to replace the director. It was in production in southern Africa, and that became my first feature as a Director. THa: I saw it in Palads Teatret. With Reese Witherspoon. Beautiful pictures. Mikael: That's right, she was only 16 when we shot it. Yeah, that was pretty. That was anamorphic Panavision. They had started shooting in Africa in the jungle with only two 10K lights and shooting anamorphic with only that amount of light is nonsense. I mean, it's ridiculous. It turned out that the director's friend was the gaffer (a lighting director), and the director made him the cinematographer. The guy didn't know what he was doing, and it was just miserable. So Steven said, “Well, can you use any of what they shot?” He told me if you want to start over, you have to start immediately, because they’ve been in Africa for three months already. This was on a Saturday, and on Tuesday I was in Africa directing. I replaced the camera crew, and recast some of the actors. So it was rocking the boat big time, and Reese was in tears and everybody was a bit tense. But it ended up really good, and we had a good time. I only heard from Steven once. At that time we had a satellite phone, but it was very expensive to use. So, at one point I called him asking “Have you seen …”. “Yeah. Yeah. Just keep doing what you're doing. It's great.” [laughing] |

|

"Barndommes

Gade" starring Sofie Gråbøl and cinematography by Mikael Salomon. "I

photographed Sofie [Gråbøl]'s two first feature films, "Oviri" (1986) and "Barndommens

Gade" (1986). I was working with Donald Sutherland on "Oviri", and he did

not like to be photographed with a lens below 32mm. So I changed

the label on the lens instead. He became a little upset when he found out one day."

Poster display at the Biograf Cafeen cinema in Vordingborg, Denmark. Photo

credit: Thomas Hauerslev "Barndommes

Gade" starring Sofie Gråbøl and cinematography by Mikael Salomon. "I

photographed Sofie [Gråbøl]'s two first feature films, "Oviri" (1986) and "Barndommens

Gade" (1986). I was working with Donald Sutherland on "Oviri", and he did

not like to be photographed with a lens below 32mm. So I changed

the label on the lens instead. He became a little upset when he found out one day."

Poster display at the Biograf Cafeen cinema in Vordingborg, Denmark. Photo

credit: Thomas HauerslevTHa: I've got a question about “Always” (1989). The beginning of the film, where you have two men in the boat, and the aeroplane coming towards you. That's a long lens, and it looks great … Mikael: Yes, thanks. It really was difficult. We actually had to scout the shot in the helicopter, because it was shot with a 600 millimetre lens to make it get really compressed, so trying to figure out exactly where that plane was going to come down was critical. If he was off to the side by like a metre or so, he'd be out of shot. THa: How many takes did you do? Mikael: We only did it once. THa: Looks great. Mikael: Yeah, there's no tricks in that one. THa: You worked with Audrey Hepburn there. How was that? Mikael: Yeah, that was amazing. Of course we didn't realize that it would be her last movie. She was lovely. Absolutely lovely. THa: Does your background as a DP [Director of Photography] influence the way you have worked as a director, and in what ways? Mikael: I think what it does, it makes life easier for the DPs I’m working with. I mean, I've had wonderful experiences with the [camera people] I've worked with. Over and over again. So, say, for example: imagine you're standing on a building on a city square, you're looking down, there's a couple of streets here at night. It’s a night shoot and you tell the DP, for this scene, “I'd really like to go over here, over there, and we’re looking down both streets, right?” Then, as a DP, you’ll reply, “Yeah, sure, I can do that. It's going to take me probably two hours to light it” or something like that. But I also know that, as a cameraman, that if I can move the camera little bit to the left (or right), so I don't have to look down these streets, he can be ready in 15 minutes. As a director I can make that choice, whereas if you're a cameraman, you want to give the Director what he's asking you to do. You want to give the director exactly what he's asking for. But since I have been a DP, it's much easier for me to say, “I don't need to look down this street. I need the time. So why don't we just move over here?” So we just look down one street and save one hour? You know, it's kind of practical. Also, when you block a scene -- you know, when you figure out the general location of where people gotta go and where the camera is going to be -- sometimes I would say, “OK, Let’s do it here.” Then the cameraman might say, “Can we mirror reverse the set up, so that we're on the dark side of the actors, so you don't get flat lighting, and get something more from the sides?” Of course you can. Whereas, I've shot movies as a cameraman for maybe 12 first-time Directors. In my opinion there are two kinds [of Directors], there’s the ones that come in and say “OK, Spielberg, stand back and I'll show everybody how this is done”. With a person like that you just say, “OK, where do you want to put the camera?” Whereas others come and say, “This is new to me. I've never done this before. I think I have some good ideas. I need your help. I need everybody's help.” You’ll go through fire and water for that person. I've heard Steven [Spielberg] say “Bring me all your ideas. I'll get the credit anyway” [laughing]. That's when you're confident in what you do. As a cameraman, I always felt confident going on to the set because I knew it might not be that pretty, but I know I can work my way out most situations. THa: Sometimes you read stories about it, where it's the cameraman who saves the day, if the director is impossible... Mikael: Yeah, because from experience, the DP knows what to do. I had an experience here in Denmark that wasn't that great. It was the same thing. And then they said “Do you want to take over this show, because we agree with you, that this guy is not doing a good job”. I was young, and that time I told them I would NOT take over the show, because if I did that, I'd never get another job as a cameraman, if I got the director fired. They have to bring in another director. I was happy to finish that show as a cameraman, but certainly not as a director. Mikael: [shows a “Far and Away” set-picture on his phone] THa: Oh, that's fantastic. What a huge lens Mikael: Yeah, that's a long lens. The problem was the lenses we had [on “Far and Away"] were not all Panavision lenses, really. They were all different kinds -- Nikons and what have you -- all because they were spherical, and they [Panavision] didn't have time to build as many as I needed. So we took a Hasselblad here and a Nikon there. A lot of Nikons, and some of them had problems in the corners. You'll see some of the images have a little vignetting. Just a little bit. That's from the lens not quite being able to cover the whole [65mm] frame. • Go to Stanley Kubrick's "2OO1: A Space Odyssey" in Super Panavision 70 • Go to "Oppenheimer" filmed in 65mm with IMAX cameras THa: Since you were shooting in 65mm with these brand new cameras, did it attract any special attention from the actors? Mikael: Yeah, especially from Tom Cruise. He was all into it, and he was also into the sound. He was great to work with. Now they all were in on the fact we were allowed to shoot in that format. Everybody had a “memorable 70mm experience”. For example, as I said, I was at the [London] premiere for "2OO1" with my dad, when I was a kid, so that blew me away. I remember saying to myself, “I have got to do something like this. Don’t know how, where or when" ... but it was in my mind for years. |

|

"... the

[70mm] process was simply curiosity. I mean, I'd like to

play with all the toys. And so why not that?" Mikael Salomon. Photo credit: Thomas Hauerslev "... the

[70mm] process was simply curiosity. I mean, I'd like to

play with all the toys. And so why not that?" Mikael Salomon. Photo credit: Thomas HauerslevTHa: What does in 70mm mean to you? How would you describe the experience of seeing a film in 70mm? The example these days is Christopher Nolan with "Oppenheimer". He says it is like looking out of the window, because it's so hyper-real: crisp and clean. Mikael: You mean when I see it on a poster? Sometimes people don't want crisp and clean, you know? But I'm a technician also, and obviously I enjoy it of course. I'm really surprised that he [Christopher Nolan] was able to shoot in IMAX in 65 because it is VERY expensive. But of course, if your film brings in a billion dollars, then there's money for it. THa: What are your favourite 70mm shows, if any, and why? Mikael: Good question, that's definitely “Lawrence”. Without a doubt, it still holds up brilliantly. It's gorgeous. So every time you see “70” on the poster, of course you have to go see it. It is a different dimension you get. It's a whole different feel. I never felt "Zhivago" was as good a movie, and it didn't feel as epic as “Lawrence of Arabia”. • Go to Some Notes on Shooting "Lawrence of Arabia" • Go to Facts For Editorial Reference About The Making Of Doctor Zhivago • Go to Memories of Ryan's Daughter THa: Is it important to you to see films in the cinema compared to TV or Blu-ray? Mikael: Absolutely, right. Yeah. I mean the problem is now with with Blu-ray and at home, I mean, I had kids in L.A., so we didn't get out that much. I would go to a lot of the Academy screenings because you knew you'd see the best screening possible. I just saw ”The Color Purple” down here at the Movie House [Cinema in Copenhagen]. It was really a great screening, fantastic screening, fantastic sound and Dan Lausten [DK DP] you know, he did a wonderful job. So that's great. The first thing I bought when I came here this time was a 75 inch [TV]. I can watch all the Academy movies I want. So you see them in a really good quality. It's hard to beat. Plus in my own home theatre in L.A., the sound is incredible. You sit right in the sweet spot. Not over here or back there. Here, right here where the optimal sound is. And there's nothing like it. THa: You have had a long career in the US by now. How does it feel to walk in the footsteps of other Danes in Hollywood? How does that make you feel being Mikael Salomon in that community? Mikael: Which community - in L.A.? THa: Yes, being a Danish Cinematographer / Director working in Hollywood for so long. Mikael: One of the things I really enjoyed when I came to L.A. at the beginning was, you come to a set in Hollywood and 50% of the people around you are not American. They were very open to people coming in. It was very open, and very open to my ideas. They knew I had certain accomplishments, because otherwise I wouldn't be there. So no, they were loyal. I always felt Danish, but I also felt I belonged in L.A. to work. That was sort of the ultimate toy, and as a cameraman, you like the toys. You like the gadgets, and I had to challenge myself. THa: You certainly did. How did you experience working in Hollywood, walking in the footsteps of other great Danes. You mentioned that it's a melting pot of all kind of nationalities. Mikael: It is a melting pot. But you know, what I would say, Jean Hersholt was too far away from me. I mean, there were really very, very few Danes in L.A. at the time I arrived. Most Danes don't stick there, including myself. You see, I'm back here now, but that's because of the political situation. I think a country where they allow children to be shot every day in the schools is not a country I want to stay in. I think that's horrendous, and they still won't do anything about it. I think that, when you have kids – well, I pity the people who have kids in schools these days, because I still have kids in school, and I fear the moment that call may come in. You know that's not right. Denmark has so much going for it, just not the weather [laughing]. No, it's magical over there in many ways, but my life was a working life, you know. THa: Last year I turned 60. And one of my friends said welcome to the third act. You're well into your third act. What are your future plans? Mikael: To go to the fourth act. [Laughing] |

|

| Go: back - top -

back issues -

news index Updated 22-01-25 |