"Motion"

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: American Cinematographer, August 1967 | Date: 12 September 2006 |

Canadian

Nation Pavilion Canadian

Nation PavilionThe auditorium is thrown into darkness and the screen lights up. An airplane nose-dives earthward through the clouds . . . a baby takes her first worldly step . . . a small girl laughs happily as she swings slowly backwards and forwards on a 75-foot swing . . . teenagers gyrate to deafening music in New York's Cheetah Club . . . a space craft is slowly lifted off its launching pad to the roar of igniting rockets . . . American astronauts "walk" weightlessly in space . . . the shattering thud of a house crumbling under the impact of a bulldozer is juxtapositioned with the tumble of a head-on collision in a football game . . . and dozens of whirling bicycle wheels give way to the thundering of a horse stampede, and then to the silent flight of wild geese. Only a film can present such a variety of experience in the short space of 14 minutes. The title of the film is “Motion” and it is being presented by Canadian National Railways in its Pavilion at EXPO 67. A few sentences, spoken in English and French, are the only narration. For the rest, the film tells, through an unusual and imaginative use of photographic techniques, what motion means to man and how it affects man from his birth to his death |

More

in 70mm reading: The Passing of Bob Gaffney, 1931 - 2009 "Sky over Holland" "Motion" Film Credits MCS 70 - Superpanorama Jan Jacobsen "Fanny's Wedding" Internet link: Bob Gaffney on imdb.com Robert "Bob" Gaffney (08.10.1931) |

Bob

Gaffney credit in "Sky over Holland" Bob

Gaffney credit in "Sky over Holland"“Motion” is an extraordinary cinematic achievement. Except for a few split-screen compositions it relies on no format gimmicks whatsoever to create its stunning impact upon the audience. There is only breathtaking 70mm photography, dramatic action and a soaring musical score . . . but all this adds up to one of the most beautiful films being presented at EXPO. Man employs motion for enjoyment, entertainment and thrills and the film dwells on many of these uses. Among the film's most exciting footage is the first free fall parachute drop ever filmed in 70mm. The free-fall sequences were shot in California, but the film also includes many scenes filmed all over the world. One of the most memorable sequences in the picture is a funeral, filmed in New Orleans' famous Bourbon Street. After the sombre hymn singing and wreath-laying, the funeral party marches off to a band's brassy rendering of "When The Saints Go Marching In." |

|

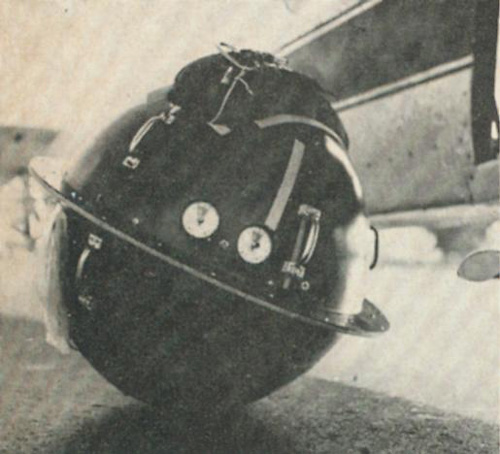

This black, fibre glass sphere is the behind-the-scene. star af Canadian

Natianal Railway's film “Motion”. It took 2½ months to design

this capsule which haused a $25,000 M.C.S. camera used to shoot the

first free-fall sequence ever filmed an 70mm. This shape was engineered

to fall freely through space at the same rate as the jumpers, 125 mph. This black, fibre glass sphere is the behind-the-scene. star af Canadian

Natianal Railway's film “Motion”. It took 2½ months to design

this capsule which haused a $25,000 M.C.S. camera used to shoot the

first free-fall sequence ever filmed an 70mm. This shape was engineered

to fall freely through space at the same rate as the jumpers, 125 mph.

Produced in 70mm color and shown on a 40 foot curved screen with full stereophonic sound, CN's “Motion” is essentially a fun-film. From time to time, to give added impact and variety, the single 7Omm screen breaks into triple screen technique. The film was produced by CRAWLEY FILMS LIMITED of Ottawa which brought together a talented production team that included: Eric Boyd-Perkins, sound editor for many well-known feature films; Tony Gibbs, consulting editor, whose credits include TOM JONES and THE KNACK ; Vince Vaitiekunas, director-editor, whose Canadian documentary and television work includes the former CBC program THIS HOUR HAS SEVEN DAYS, and Robert Gaffney, Director of Photography. The music score was composed and conducted by Larry Crossley. |

|

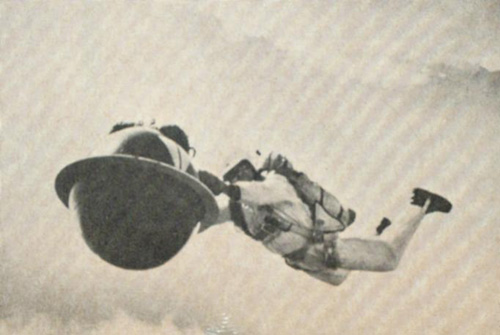

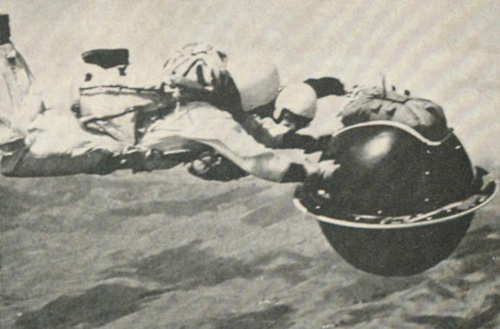

Hurtling earthward at 125 miles an hour, a California sky diver steadies the

camera capsule. The sequence look 2½ months of testing and over 50 jumps

before it was ready for the 14-minute, 70mm film, produced by Crawley Films,

Ottawa. Hurtling earthward at 125 miles an hour, a California sky diver steadies the

camera capsule. The sequence look 2½ months of testing and over 50 jumps

before it was ready for the 14-minute, 70mm film, produced by Crawley Films,

Ottawa. After more than 50,000 feet of film and six months in the making "Motion" is running 33 times daily in CN's 200-seat theatre. Filming some of the complex and unusual sequences for “Motion” amounted to a kind of cinematic obstacle course, and it included at least one unique problem: How do you get a 65-pound camera, falling 12,000 feet at the rate of 125 miles an hour to properly photograph a group of free-falling skydivers? This is the challenge that Director of Photography Robert Gaffney took on to produce one of the most exciting sequences in the picture. |

|

Sky-divers show haw exciting free-fall parachute drop was filmed

for “Motion”. Sky-divers show haw exciting free-fall parachute drop was filmed

for “Motion”.Gaffney, whose credits include “Windjammer”, “Cinerama Holiday”, “Vigllant Switzerland” (nominated for an Academy Award), and "Sky over Holland", has been involved in Cinerama, Todd-AO and other wide screen processes since 1955. However, the problem of capturing the 60 second free fall sequence on 70mm was one of the most challenging experiences he has encountered, and he spent more than three months researching and testing various methods of shooting the sequence. Gaffney, who works out of Seneca Productions in New York, likes the realism involved in putting speed and excitement on the big screen. "It's always intrigued me," he says, "that by using the big camera and a wide angle lens and putting it in the position of being the pilot- driver, or sky diver, you can give viewers in the audience an experience they could never attain themselves." |

|

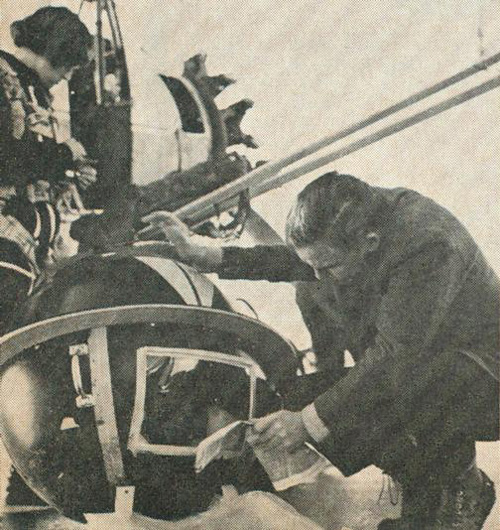

With the 70mm camera in place, director of photography Robert

Gaffney makes a final inspection of the capsule containing the M.C.S.

70mm camera. The capsule was tossed from the plane at an altitude of

14,500 feet. It took 2½ months lo perfect techniques that would allow it

to fall al the same speed as six free-failing jumpers. With the 70mm camera in place, director of photography Robert

Gaffney makes a final inspection of the capsule containing the M.C.S.

70mm camera. The capsule was tossed from the plane at an altitude of

14,500 feet. It took 2½ months lo perfect techniques that would allow it

to fall al the same speed as six free-failing jumpers.It was while filming at the Reno Air Races late last year, that Gaffney met Bill Berry, a hot air banoonist from Concord, California. Berry and his 75-foot high balloon appear in “Motion” and it was he who first got Gaffney interested in trying to film a sky diving sequence in 70mm. The first tests took place at Reno, Nevada, where Gaffney experimented with the conventional methods used when filming sky diving in 16mm or 35mm. These involve attaching the camera to one of the jumpers. But the weight and size of the bulky German built MCS reflex camera, equipped with a 25mm wide angle lens, posed problems from the start. A rectangular box was made to house the camera and it was strapped to a jumper's chest. |

|

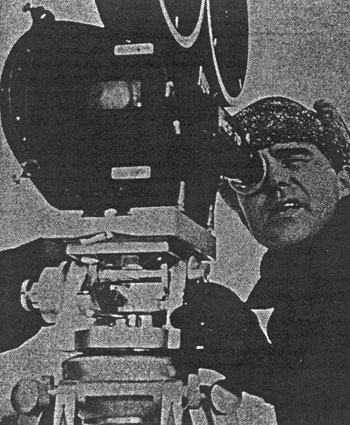

Robert Gaffney. Director of

Photography for “Motion” and “Sky

Over Holland”. Both are" cameraman's pictures.' and owe much of

their impact to his camera artistry. Robert Gaffney. Director of

Photography for “Motion” and “Sky

Over Holland”. Both are" cameraman's pictures.' and owe much of

their impact to his camera artistry.However the unit did not allow the diver freedom of movement and during the first fall he experienced dangerous lack of control and had difficulty pulling the rip cord to release his parachute. On another attempt the box housing the camera slipped and one arm became entangled in the straps, causing a jarring, one-arm-controlled descent after the chute opened. It was at this stage that Gaffney decided the camera must fall as a separate entity, much to the relief of the sky divers. Re and Bill Berry moved the project to California. Berry began organizing the sky divers, a group cantered in Livermore, with an average of over 1,000 jumps each to their credit. Then began two months of tests and consultations with physicists, professors of aerodynamic sciences and missile experts. The big problem was to come up with a container of the right shape and weight which would drop in a stable fall and at the same rate of descent as the sky divers. From a great variety of designs, ranging from boxes to bombs, a spherical shape with a stabilizing ring around it was found to work best. The camera required the case to be a minimum of 26" wide by 24" high by 18" in depth. The capsule was made from durable fibre glass and metal. Black in color, the jumping crew nicknamed it the "eight ball". |

|

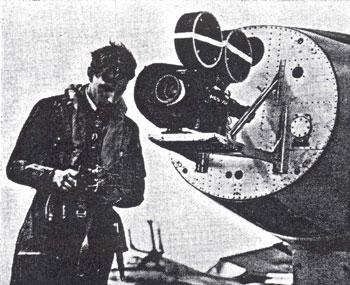

Using the top of his "bug" as a camera platform, Gaffney sets up

to photograph horse fair. Using the top of his "bug" as a camera platform, Gaffney sets up

to photograph horse fair. The lens window was covered with plexiglass and two barometric pressure devices were installed to automatically open the parachute at a height of 2500 feet. Then came a series of tests without the camera, to determine what the unit should weigh to provide the proper control. The first test indicated more weight was needed. On the second drop, the automatic firing devices failed to trigger the chute and Gaffney watched the capsule plummet to the ground and smash to pieces. Another capsule was built and a manual opening device was added. In this manner, the diver could trigger the parachute himself and only if he failed, would the barometric device be activated. Using this method the correct total weight of the camera, film, and capsule was quickly found to be 195 pounds. The unit was weighed accordingly and shooting began. To achieve a 60-second free-fall, divers must jump from 14,500 feet-and at that height, the chilly winter air over the central California location was between 20 and 30 degrees below zero. For complete safety, jumpers must pull the rip cord by the 2000-foot level. Allowing 15 seconds after leaving the plane to reach the camera and get in position and another 15 seconds to break formation and release the chutes, left only 30 seconds of free-fall filming on each jump. The battery-driven camera was usually turned on before it was pushed from the open-door Fairchild aircraft. It was up to the control diver to shut the camera off and pull the rip cord as he pushed away from it. |

|

The nose of this Dutch Airforce "Hunter" jet was specially

rebuilt to mount the M.C.S. 70mm camera. The nose of this Dutch Airforce "Hunter" jet was specially

rebuilt to mount the M.C.S. 70mm camera.There were more than 50 jumps made over the entire period. Success finally came over a three-day span when five good six-man jumps were caught on film. On one jump air currents tore the camera out of the hands of the jumper and the capsule began spinning wildly. But as it tumbled earthward it shot a magnificent series of pictures as the divers tried desperately to grab the camera on the way down. As it turned out the automatic release triggered the parachute at the 2000 foot level and this footage was used in the final film. For Gaffney, who watched every jump from the ground, the hardest part of the entire assignment was "looking up to see that $25,000 camera hurtling down toward earth at 125 mph and waiting for the parachute to open." Fortunately, except for the dry-run failure, it opened every time. As a result, visitors to CN's EXPO pavilion can see for themselves, some of the most exciting film footage ever to go through a 70mm camera. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|