|

| | A History of Widescreen and Wide-Film Projection Processes | Read more at

in70mm.com

The 70mm Newsletter

| | Written by: Les Paul Robley, Film & Video Critic, Los Angeles, USA With additional research by Dan Sherlock | Date:

09.02.2010 |

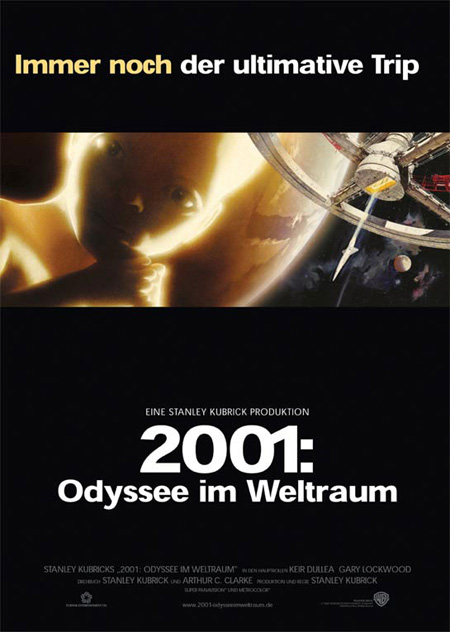

To supplement the American Cinematheque’s fine efforts to “resurrect” 70mm with 2008’s Easter Sunday presentation of “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” as well as the Motion Picture Academy’s 40th Anniversary screening of “2001: A Space Odyssey” at the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre in Beverly Hills, I thought it might be appropriate to chronicle a brief history of widescreen and wide-film highlights from the birth of cinema to the present day. To supplement the American Cinematheque’s fine efforts to “resurrect” 70mm with 2008’s Easter Sunday presentation of “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” as well as the Motion Picture Academy’s 40th Anniversary screening of “2001: A Space Odyssey” at the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre in Beverly Hills, I thought it might be appropriate to chronicle a brief history of widescreen and wide-film highlights from the birth of cinema to the present day.

ANAMORPHOS: Derived from the Greek term meaning “to form again,” the anamorphic theory was patented by David Brewster in 1862. Several more were patented since 1898. These found little use other than lab and military applications. The first actual lens was introduced by Italy’s Ernst Zollinger for an additive color process in 1910. But its first use as a projection device didn’t arrive until 1930, courtesy of Dr. Sidney Newcomer. French physicist Henri Chretien developed a similar “squeeze” lens called Anamorphoscope in 1927, which was optioned for six months by Paramount in 1929 and subsequently dropped. Twentieth Century-Fox later acquired the process in 1952 as a basis for Cinemascope.

CYLINDROGRAPHE: Probably the earliest widescreen projection process invented by Moessard in 1884.

BIOGRAPH PROJECTOR: The first wide-film format was said to have displayed footage of the Thames River rowing tournament known as the Henley Regatta, which was projected in 1896, but may have been filmed as early as 1894. It required a special projector built by Herman Casler of Canastota, New York and possessed an aperture of 2.75 inches by 2 inches. Casler had earlier invented the “Mutoscope” which displayed short films via flip-cards rotated by a hand crank, unlike Edison's motorized “Kinetoscope,” in which films were viewed on actual 35mm film. The prototype of the Mutograph camera was completed in November 1894, and the first official Mutoscope films were made in August 1895. To avoid infringement on Edison's motion picture patents, the Mutograph camera used continuous friction rollers to run 68mm film through the camera, instead of an intermittent sprocket-movement as with Edison’s 35mm camera. Casler's patents were granted in January 1896 and used as security for financing his new company. The Mutoscope became as popular in nickelodeon parlors as the Kinetograph. However, the first public demonstration of projected motion pictures in the United States had already occurred in April 1895. Casler then designed the Biograph Projector, which was introduced on a tour of vaudeville houses in Sept-Oct 1896. The projector’s 68mm film offered four times the image area of Edison's 35mm film—a substantial improvement not lost on early viewers—and both the Mutoscope and Biograph enjoyed great success. In 1899, the company’s name was changed to American Mutoscope and Biograph.

CINECOSMORAMA: The earliest multiple camera/projection process, Cinema-In-The-Round, was first patented under the name Cinecosmorama by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson on Nov. 27, 1897. It consisted of ten radiating cameras allowing 360-degree filming and projection, similar to Disneyland’s current Circle Vision 360. The name was later changed to Cineorama for the 1900 Paris Exposition.

CINEORAMA: Invented by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson, the 35-year-old film pioneer began experimenting with movie cameras and projectors in 1895. It consisted of 10 synchronized 70mm projectors displaying associated images onto ten 9 x 9-meter screens arranged in a full 360° circle around a viewing platform. The audience was seated in what resembled a large balloon basket, capable of holding 200 viewers, with rigging, ballast and the lower part of a huge gas bag hanging above. Cinéorama became an amusement attraction at the 1900 Paris Expo to simulate a hot air balloon ride over Paris. It was shut down after three days for safety reasons.

LUMIERE WIDESCREEN: This 75mm large film format was invented by pioneer French cinematographers Louis and Auguste Lumiere. Later, after directing some 60 films and producing over 2,000, the Bros. Lumiere abandoned film production and devoted their energies to the manufacture of photographic equipment and 3-D.

WIDESCOPE: Invented by George W. Bingham in 1921, this double lens system imaged scenes onto two separate films. The two films were then shown using two interlocked projectors.

MAGNASCOPE: This special technique usually accompanied the last reel of a film in order to make its climax more powerful, about four times larger than normal when projected onto a huge screen. The patent describes it as switching to a different projector equipped with a shorter focal length lens to create a wider image, and the masking is opened up revealing the larger screen. Some lenses were marketed as “suitable for Magnascope” in order to achieve the shorter focal length. The process was developed for Paramount by Lorenzo Del Riccio and lasted nearly 30 years. Although the technique had been used previously on films presented at the Eastman Theater in New York, its first wide usage under the term “Magnascope” was for the feature film “Old Ironsides” in 1926. One of its most memorable displays accompanied the green-tinted tidal wave sequence at the end of “Portrait of Jennie” (1948).

| More in 70mm reading:

Fabulous Technicolor! - A History of Low Fade Color Print Stocks

Internet link:

Les Paul Robley

40 Sunset Circle

Westminster

CA 92683-8000

USA

IBsonly@aol.com & mymo_co@yahoo.com

|

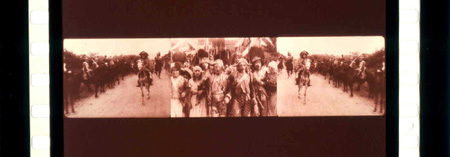

POLYVISION: A triptych or 3-panel process developed by Abel Gance, giving a pre-Cinerama effect to his 1927 “Napoleon.” Parts of the film were shot with three synchronized cameras and projected onto a wide triple screen, adding scope to the film’s action sequences which contained thousands of extras. Gance also filmed some scenes in color and 3-D, but decided against their inclusion in the final print. A true innovator, Gance even suspended his cameras from wires and strapped them to the backs of galloping horses. Following its debut in Paris, the film was said to have been presented in triple-screen format in seven other European cities. MGM decided against releasing the Polyvision format in America as it feared further calamities caused by the transition to sound. Gance experimented adding stereo sound effects to “Napoleon” in 1934 and a new process called “Magirama” in the fifties. Later, Francis Ford Coppola released the film in its intended format, complete with a new score by Carmine Coppola. POLYVISION: A triptych or 3-panel process developed by Abel Gance, giving a pre-Cinerama effect to his 1927 “Napoleon.” Parts of the film were shot with three synchronized cameras and projected onto a wide triple screen, adding scope to the film’s action sequences which contained thousands of extras. Gance also filmed some scenes in color and 3-D, but decided against their inclusion in the final print. A true innovator, Gance even suspended his cameras from wires and strapped them to the backs of galloping horses. Following its debut in Paris, the film was said to have been presented in triple-screen format in seven other European cities. MGM decided against releasing the Polyvision format in America as it feared further calamities caused by the transition to sound. Gance experimented adding stereo sound effects to “Napoleon” in 1934 and a new process called “Magirama” in the fifties. Later, Francis Ford Coppola released the film in its intended format, complete with a new score by Carmine Coppola.

HYPERGONAR: A widescreen process developed concurrently with Polyvision that varied the shape and size of the middle screen using an anamorphic lens dubbed “Hypergonar.” It was invented by Professor

Henri Chretien for an additive color process. He later filed another patent for its use in widescreen. The lens accompanied director Claude Autant-Lara’s short film, “Pour Construire un Feu” (“To Build a Fire” 1928), an avant-garde adaptation of a Jack London story. After producing several short documentaries, the system was soon shelved for lack of commercial acceptance. Much later, the lens was acquired by 20th Century-Fox for the studio’s Cinemascope process.

NATURAL VISION: A 63.5mm film process developed by George Spoor and John Berggren that supposedly produced a curious stereoscopic effect when projected onto two 50-ft wide screens. One screen was said to be transparent and the other opaque. Although Spoor hyped it as “3-D,” it was not truly stereoscopic, and no evidence exists that a transparent screen was ever used in public demonstrations. RKO premiered the process with the film “Danger Lights” (1930) starring Jean Arthur and Robert Armstrong, although the 63.5mm cameras were utilized earlier on the 1925 film, “The American,” which was never shown to the public.

| |

GRANDEUR: A competitor to Natural Vision owned and financed by William Fox that premiered in 1929 with newsreel footage of Niagara Falls. Technically similar to Todd-AO, it failed when theatre owners refused to install the necessary equipment. The main difference was that 70mm Grandeur had a four perforation pull-down (i.e. each frame occupied the height equivalent to four perfs on the film) rather than the 5-perfs used by Todd-AO and current 70mm processes. A small number of shorts and features were produced in Grandeur. These included several Fox Movietone News, referred to as “Fox Grandeur News,” the feature “Fox Movietone Follies of 1929” and the Grandeur short “Niagara Falls”—all premiering together in New York on September 17, 1929.

Also, Grandeur enhanced the musical “Happy Days” (1929), directed by Benjamin Stoloff, plus Raoul Walsh’s “The Big Trail” (1930), noted for its grand sweep, naturalistic use of sound and “discovering” of John Wayne. Filming for “The Big Trail” began in April 1930 and the film was shot simultaneously in Grandeur and conventional 35mm. Both versions are said to exist, and (like Fox’s initial films made in Todd-AO) differ significantly in composition, staging and editing. When the film was released, the only theaters equipped to present it in Grandeur were Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and Carthay Circle in Los Angeles, and the Roxy Theater in New York City. Grandeur was one of a number of widescreen processes developed by the major studios in the late 1920s and early 30s. The Great Depression and the enormous costs converting thousands of theatres to sound had already thwarted the successful completion of any of these systems on a commercial scale. When widescreen did become a viably successful technology in the mid-fifties, the three major systems—Cinemascope, Todd-AO, and VistaVision—all drew heavily on the results of this initial phase of research and development, of which Grandeur was arguably the most successful. In 1958, director George Stevens even considered shooting his “The Greatest Story Ever Told” in Grandeur (then probably CinemaScope 55 with Todd-AO compatible reduction prints).

MAGNAFILM: Del Riccio’s second process employed a 56mm film size to add an improvement over the picture quality provided by Magnascope. Noted for incorporating a 2 to 1 width-to-height aspect ratio, it was demoed to the press on the short film “You’re in the Army Now” (1929).

REALIFE: MGM’s 70mm widescreen process was converted to standard 35mm film for projection with a wide-angle lens. What distinguished this from other lens processes was its “pre-VistaVision” optical reduction technique which improved the grain of the release print. Premiered with King Vidor’s early talkie Western “Billy the Kid” (1930) starring Wallace Beery and Johnny Mack Brown, later re-titled “The Highwayman Rides.”

MAGNIFILM: Born December 25, 1878 in Rybinsk, Russia, Joseph Schenck produced the bizarre whodunit "The Bat Whispers" (1930), a film directed by Roland West and noted for its innovative dolly transitions from miniatures to live action that was simultaneously filmed in an experimental 65mm process. Schenck founded 20th Century with Darryl Zanuck and became the company’s president, later merging with Fox in 1935. He resigned his position as chairman in 1941 after being sentenced to a year in jail on income tax irregularities. He formed

Magna Corporation with Michael Todd in 1953 to further the wide-film Todd-AO format.

VITASCOPE: Warner Bros. Studio was not to be left out of the wide-film race and premiered its 65mm process on “Kismet” in 1930.

GEORGE HILL: The British inventor of a double 35mm frame process that ran film horizontally through the camera, pre-dating Paramount’s VistaVision by 25 years.

GIANT EXPANDING PICTURES: Invented by a projectionist at London’s Regal Theatre, this wide-film process was quickly abandoned by theatre owners already up to their ears in new sound equipment.

| |

VITARAMA: Fred Waller, an

engineer at Paramount’s special effects department, developed his 1937 process of 11 projectors covering a curved screen with a one-quarter dome—an amalgamation of our present Omnimax and Circle-Vision 360 screen formats. The invention’s intended premiere was scheduled for the petroleum exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, but sponsors changed their minds and it was not shown.

CINERAMA: The infamous roller coaster ride in “This Is Cinerama” premiered at New York’s Broadway Theatre on September 30, 1952, and subsequently brought the house down. Waller simplified his earlier Vitarama by using three 35mm cameras to record scenes vertically onto 6-perforation film, 1.116-in. high x .996-in. wide, the combined negatives twice the imaging area of 70mm. Three selsyn-interlocked projectors—traditionally known as Able, Baker and Charlie—projected separate prints onto left, center and right-hand thirds of a deeply-curved screen, recreating a 146-degree horizontal viewing angle that closely matched human vision. The screen consisted of vertical overlapping strips of perforated material, presenting a continuous appearance to the audience. The joins were annoyingly visible since the slightest film-weave in each projector gate magnified greatly on the screen, resembling a poorly executed matte shot. To help hide the joins between images, each projector possessed oscillating steel combs, called giglos, mounted at the sides of the gates. These were driven by a cam on the shutter drive shaft to eliminate any double-brightness effect when the two images overlapped. The soundtrack was provided by a 7-channel sound system dubbed onto 35mm full-coated magnetic film that was interlocked with the projectors. Five tracks fed 5 speaker systems located behind the screen, with two-channels feeding 8 more speakers distributed at the sides and rear of the auditorium. Tracks 6 and 7 were manually switched between stereophonic and monophonic surround by theatre engineers, plus “back surround” was cued-in for selected scenes. The second act of “This Is Cinerama” opened with Lowell Thomas demonstrating the multi-channel sound without image. Blank spacer was spliced onto the head of each of the three reels of picture in order to maintain sync. When Cinerama was first introduced in 1952, between 10 to 17 projectionists and engineers were needed to run it. Waller died two years after Cinerama’s debut.

Although some sources credit "How The West Was Won", as the first Cinerama story-themed feature, “The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm” (1962) became the first fictionalized story filmed in the process. The 3-panel system lasted only 10 years, but its debut initiated the widescreen craze of the fifties and permanently ended the 1.33:1 format. This caused a widescreen panic among the studios, similar to what occurred with the transition to sound. Some feel we would not have Panavision—or even 1.85:1—were it not for Cinerama. “This Is Cinerama” was subsequently reissued in a cropped 70mm format in 1973. Unfortunately, the cropping eliminated a large percentage of the side images since the film was not optically corrected. Previously it was considered possible to use an Ultra Panavision Cinerama 65mm squeezed negative (on single film) and optically print three separate 35mm release prints that could display the same picture in 3-projector Cinerama installations. However, it was deemed advisable to prepare special etchings on the camera viewfinder ground glass to indicate the anticipated 3-panel areas, so that actor’s faces would not be “split” into adjacent panels. Even though the financial success of “How the West Was Won” (1962) breathed new life into the process, work on this single-film version died when the company was acquired by California-based Pacific Theatres. Also, audiences couldn’t tell which scenes had been shot in 3-strip Cinerama against action shot on single-film Ultra-Panavision 70. And technical limitations resulting from the ultra-wide viewing angle did not favor story-themed movies.

Filming

of "The Eight Day". Cinerama camera is visible at seaside just to the

right of submarine going into water. Image by LIFE Filming

of "The Eight Day". Cinerama camera is visible at seaside just to the

right of submarine going into water. Image by LIFE

Although Cinerama was an East-coast invention, the West never did it justice and the now-famous Pacific Cinerama Dome on Sunset and Vine was considered, at the outset, poorly designed. Even single-strip films were not shown in the best light. George Stevens had planned to do “The Greatest Story Ever Told” since 1948 in various widescreen processes, including Cinerama in 1965. Following three days of filming with the 3-strip camera, the production switched to Ultra-Panavision 70. Despite spectacular vistas, it proved to be “The Most Tedious Movie Ever Projected!” In 1956, in cooperation with the U.S. Army and the Atomic Energy Commission, Cinerama started filming “The Eighth Day,” a documentary about the rise of atomic power. Production was abandoned after only two sequences were completed. (Somewhere there may exist 3-strip footage of an actual nuclear test!) An Australian film collector in Sydney I met has a Cinerama setup in his backyard where, during summer months, he displays an actual 3-panel film using three interlocked projectors, while serving guests “a steak on the barbie.”

1.85 WIDESCREEN: Today we call it flat, but back in the fifties this proved an economic approach for filmmakers trying to capture viewers away from their television sets. In fact, British posters for Hammer films advertised their movies with “Filmed in Technicolor Widescreen,” even though they were only shot with normal spherical lenses on standard 35mm film. The 1.85:1 ratio is determined by dividing the width of the picture by the height. It is by far the most common aspect ratio for U.S. motion pictures, where as 1.66:1 was preferred for a while in European countries. This typically presented problems when showing foreign films with subtitles in mainstream domestic houses. However, now 1.85:1 is considerably more common than 1.66:1 for newer movies produced outside the United States.

Films that lend themselves to the 1.85:1 format are interior dramas or more intimate subject material, since close-ups fill the entire frame. Those that involve wide panoramic vistas or action spectacles are normally associated with 2.35:1 Cinemascope. However, 1.85 has the same potential for achieving the width of a scope image, but there will be greater headroom in the composition. This often makes the camera person’s job more difficult when bringing lights close to the area of composition or when hiding ceilings within sets. This is why many films of the sixties chose to shoot with a 1.66 hard matte in the frame, enabling more freedom for cinematographers to light their subjects without fear of grip equipment or microphones showing up in the projected image. As 1.85 widescreen requires the use of shorter focal length lenses compared to anamorphic, greater depth-of-field is possible with less focusing problems. Even though spherical lenses are typically sharper than anamorphic lenses, the 63 percent increase in negative area of 2.35 makes up for any increase in lens resolution. The smaller negative area of 1.85 makes it noticeably grainier when projected onto large screens. It is also more compatible when transferring images to video without the heinous panning-and-scanning or extended letterboxing of the image associated with scope.

| |

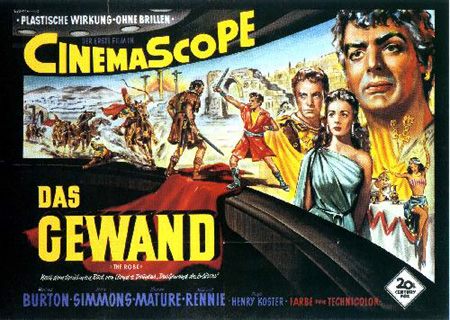

CINEMASCOPE: 20th Century-Fox’s answer to Cinerama came with an official announcement four months after the opening of “This Is Cinerama.” In order to compete against the threat of television, the studio committed to produce all their pictures in a new anamorphic process. Fox optioned the Chretien anamorphic system in 1952 under the trade name Cinemascope. It debuted at New York’s Roxy Theater on September 16, 1953 with “The Robe.” It was shot almost entirely with a lens designed by Henri Chretien (though it was simultaneously filmed flat for theatre owners who had yet to adopt the process). Within three years practically every theatre in the world was equipped to project anamorphic prints. CINEMASCOPE: 20th Century-Fox’s answer to Cinerama came with an official announcement four months after the opening of “This Is Cinerama.” In order to compete against the threat of television, the studio committed to produce all their pictures in a new anamorphic process. Fox optioned the Chretien anamorphic system in 1952 under the trade name Cinemascope. It debuted at New York’s Roxy Theater on September 16, 1953 with “The Robe.” It was shot almost entirely with a lens designed by Henri Chretien (though it was simultaneously filmed flat for theatre owners who had yet to adopt the process). Within three years practically every theatre in the world was equipped to project anamorphic prints.

The anamorphic principle is as follows: a cylindrical lens over a normal spherical lens optically compresses or squeezes the width of a 2X horizontal image to fit within the standard 35mm aperture of .868-inches wide by .735-in. high. When projecting through a complimentary lens, this produces a wide picture ratio of 2.55 to 1 with 4-track magnetic sound, or 2.35 to 1 with optical sound. (In actuality, what is called 2.35:1 is really an aspect ratio closer to 2.40:1. The original Cinemascope used a ratio of 2.66 to 1. In 1971, the camera aperture was modified slightly by ANSI to limit the projector aperture to a height of .700-inches (instead of .715-in.) to help hide splices. But the format is still referred to as 2.35:1 or more simply scope.) The horizontal compression was eventually engineered into the prime lens itself through an exclusive arrangement with Bausch & Lombe Optical Company.

According to the ASC manual, scope’s advantage offers a 63 percent increase in negative area over 1.85:1, resulting in finer grain and better opticals, and an increase in apparent picture sharpness and brightness due to the larger aperture area. (I say apparent because a similar image shot with a spherical lens is actually sharper, but the increase in grain and greater magnification make it appear less sharp. Also, the larger film aperture and greater barrel size of the anamorphic lens allows more light to transmit on screen, enabling a brighter image in footlamberts.) It is more compatible with 70mm since there is less to blow up than standard 1.85, which results in finer grain in the 70mm release print. Also, the aspect ratio is able to fill the entire 70mm frame. It’s often said that photographing a movie in anamorphic is more expensive than flat 1.85. However, the difference in cost of an anamorphic lens package is negligible, amounting to about $2,500 more over the course of a ten-week shooting schedule. In addition, Directors of Photography reveal they don’t often have to increase the size of their lighting package significantly for the wider 2.35:1 aspect ratio. On the downside, close-ups result in wide unused areas on either side of the face with the potential for distracting objects and less than satisfactory composition, as observed in 1967’s “Camelot.”

This highly successful process lasted until 1962, when it was abandoned by Fox in favor of Panavision’s lens design. Fox also introduced a lens for their low budget black-and-white features called “RegalScope.” Soon other studios and foreign countries developed their own versions of anamorphic lenses so that they wouldn’t have to rent a Cinemascope lens from Fox. These include Warnerscope (1953), Vistarama (54), Naturama (56, Republic), Cinepanoramic and Franscope (53, France), Vistascope (The Netherlands), Delrama (Dutch), Dialascope (56, France), Superfilmscope (56, Italy), Superama (58, AIP), UltraScope (58, Italy), NorwayScope, AgaScope (58, Sweden), Sovscope (58, Russia), Swiss-scope (Switzerland), Tohoscope, DaieiScope, Nikkatuscope and Sharp-scope (all from Japan), Mexiscope (57, Mexico), Alexscope (58, Argentina), Sinoscope (57, Germany), TotalScope and TotalVision (DDR East Germany), CamelScope (Egypt), Camerascope, CosmoScope and SpectaScope (50s, Great Britain), PanaScope ( a non-compatible 2 to 1 aspect ratio lens), Vistascope, AtlasScope, Videoscope (for 16mm), Fantascope (a flat-lens process referring to stop-motion special photographic effects used by Jim Danforth, Wah Chang and Howard A. Anderson on “Jack the Giant Killer” in 1962) and Giant Panamation (a re-naming of Ray Harryhausen’s Super-Dynamation process for Hammer’s “One Million Years B.C." in 1966).”

| |

CINEMIRACLE: A “seamless Cinerama” which began development in 1953 that virtually eliminated the joining lines between film strips. It premiered with “Windjammer” in 1958, detailing Captain Yngvar Kjelstrup and his crew of the full-masted training vessel “S.S. Christian Radich” as they sail around the world. Cinemiracle proved unsuccessful and the owners sold the process to Cinerama. “Windjammer” was subsequently run in Cinerama installations without the mirrors. Another project entitled “The Miracle” was abandoned in 1959 after shooting test footage. CINEMIRACLE: A “seamless Cinerama” which began development in 1953 that virtually eliminated the joining lines between film strips. It premiered with “Windjammer” in 1958, detailing Captain Yngvar Kjelstrup and his crew of the full-masted training vessel “S.S. Christian Radich” as they sail around the world. Cinemiracle proved unsuccessful and the owners sold the process to Cinerama. “Windjammer” was subsequently run in Cinerama installations without the mirrors. Another project entitled “The Miracle” was abandoned in 1959 after shooting test footage.

SUPERSCOPE: An anamorphic lens developed in 1954 by the Tushinsky Brothers for RKO which could adapt itself to any aspect ratio frame size with the simple turn of a knob.

GLAMORAMA: Douglas Leigh’s roadshow process recorded 2 ½ vertical 35mm frames in the camera. A dove prism turned the vertical image horizontally for projection onto a wide screen. Paramount later bought the system, and with minor changes, presented it as VistaVision.

VISTAVISION: An 8-perforation horizontal negative image of 1.485-in x .991-in. (twice the area of regular 4-perf 35mm film) that was later optically reduced to a standard 35mm frame. Paramount’s process was based on the Glamorama and Superama widescreen systems invented by Douglas Leigh. The studio did not rely on current anamorphic systems, such as Cinemascope, and looked for a more satisfying alternative. Their aim was to create finer-grained negatives by shooting with a double copy ratio in order that flat 1.85:1 images would be incredibly sharp when blown-up on wide screens. Paramount premiered a full 8-perf projected image with limited roadshow engagements of “White Christmas” in 1954 (with maybe only two or three prints struck in this original format).

This original 8-perf projection process proved impractical since the footage had to travel at twice the speed through the projector (180-ft per minute), doubling that of normal 35mm film, thereby opening itself up to many technical problems. VistaVision films were shown in a number of aspect ratios, the most popular being 1.85:1. Others included 2:1 and 1.75:1. The resulting release print image was of such fine grain and high quality that the process proved favorable for making anamorphic prints, as it helped compensate for the high grain found in early color negative stocks. The negative was scribed with a different kind of cue mark, created at the start of each 2000-ft reel. Similar in shape to an F, the cue contained staffs that directed the projectionist to the top of the frame for 1.66:1, 1.85:1 and 2:1. The projectionist moved the framing knob so the staff touched the top of the masking (at the appropriate ratio) and the framing was perfectly set for the rest of the reel. For shooting, the camera threading patterns were horizontal, often referred to as “Lazy 8” or “Butterfly,” because the film lay flat. Whereas most competing widescreen film systems utilized 4-track magnetic striping for stereophonic sound, VistaVision typically carried Perspecta Stereo encoded into the optical track. Perspecta was a faux-stereo system invented by Fine Sound Inc. in 1954. It was a competitor to magnetic stereophonic tracks for motion pictures, and as it did not require a new sound head for the projector, proved a cheaper alternative until its abandonment in 1958. For the same reasons, exhibitors especially liked VistaVision since the reduction prints didn’t require them to purchase extra equipment. Eventually, it too was replaced by Panavision. In 1977, the VistaVision negative was revived for the enhanced quality found in the Dykstraflex visual effects camera used for shooting motion-controlled miniatures on the first “Star Wars,” as well as improved front-and-rear-projected background plates employed in Hansard’s and Introvision’s process photography.

CINEMASCOPE 55: By 1955, in answer to Paramount’s VistaVision, Fox unveiled a new 35mm film size for the Rodgers & Hammerstein musicals "Carousel" and "The King and I", (both released in 1956). The increased negative area meant less grain and better picture resolution. Bausch & Lombe, the firm responsible for the original anamorphic Cinemascope lenses, was contracted by Fox to create new glass that could effectively cover the larger film area. The film frames yielded a projected aspect ratio of 2.55:1. Later, the larger negative size of 55.625mm (the image itself measured about 52mm) was reduced to standard 35mm film to appease irate theatre owners. In fact, unlike VistaVision, no 55mm prints of a Cinemascope 55 production were ever shown theatrically, although all Cinemascope films made between 1953 and 1957 were still shown at an aspect ratio of 2.55:1. These 35mm mag prints contained 4-channel magnetic sound using narrower Fox-hole perforations (type CS with .1870 long-pitch), unlike conventional KS or Kodak Standard perfs. This meant that movies with mag tracks could not be run on projectors equipped with the larger sprockets or perforation damage would result. When an optional mono optical track was printed alongside the magnetic stereo tracks, this reduced the image to 2.35:1. There is an erroneously held belief that Cinemascope 55 was shown at an aspect ratio of 2.35:1 using 55mm film, when in fact the films were reduction printed from 55mm to 35mm, and shown at 2.55:1. Although originally shown in this 2.55:1 aspect ratio during the roadshow screenings, at least “The King and I” was later reissued using mag-optical prints with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

For the 1950’s Disney reissue of “Fantasia” in stereophonic magnetic sound, the bulk of the sequences were presented in non-squeezed Cinemascope, since no one cared if the dancing mushrooms or hippos appeared fatter in frame. However, the Mickey Mouse Sorcerer’s Apprentice number was optically squeezed with black bars on the side as everyone knew the shape and figure of the world’s most famous mouse. This release also held the notoriety of depicting black Pikininees fanning Bacchus with palm fronds and shining hooves of the Centaurs during Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony. Fox Home Entertainment’s 50th Anniversary DVD releases of “Carousel” and “The King and I” have been made using a 2.55:1 aspect ratio for the transfer.

65MM & 70MM: The negative is actually 65mm wide sporting camera apertures of 2.072-in. x 0.906-in. The additional 5mm on the release print allows space for a 6-channel magnetic soundtrack application outside and in between the sprocket holes. The aspect ratio of 70mm release prints is 2.2 to 1 resulting in 5-perforations per frame. It contains 2 ½ times the image area of an anamorphic frame, and 3 times that of Academy Aperture. Beginning in the late fifties and continuing through the nineties, many 35mm films were blown up to 70mm for premiere showings in large cities. The larger image area of 70mm afforded sharper and steadier images on screen, and the 6-track magnetic sound proved vastly superior to the 4-channel magnetic-striped or later Dolby analog stereo tracks available on 35mm. 2.35:1 scope films can be blown up to 70mm, filling the entire 2.2 area with loss of some image on the right and left sides of frame. Additionally, 2.35:1 films can be blown up to 70mm and maintain the full width of the original aspect ratio by burning black bars above and below the image, giving the film thicker frame lines. For 1.85:1 flat films, the full height is maintained, while black bars are exposed on the unused right and left side of the picture, a la “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial"’s release at Pacific’s Cinerama Dome in 1982. Most theatres employ black acoustically-transparent masking to cover these unused areas, which transmit the Left-Extra and Right-Extra bass sound frequency speakers placed behind the screen utilized in 6-channel 70mm soundtracks.

With the advent of smaller multiplex venues and the debut of digital sound on finer-grain Eastman Kodak Vision print stocks, the number of 70mm releases declined dramatically in the nineties. Following the introduction of digital sound formats—Dolby Digital, SDDS and DTS—the significantly higher cost of 70mm lost one of its major advantages over the less expensive 35mm digital release prints. Ron Howard’s "Far and Away" (1992, filmed in Panavision Super 70 with some scenes shot in 35mm anamorphic Panavision), Ron Fricke’s "Baraka" (1992), Kenneth Branagh’s "Hamlet" (1996, with visual effects in VistaVision) and Terrence Malick’s "The New World" (2005, for the “hyper-reality” scenes only) are among the last Western productions shot on 65mm film. “The Prestige” (2006) used it sparingly — in some widescreen shots — due to the considerable price of 65mm raw stock and processing. James Cameron’s "Titanic" (1997) became one of the last big Hollywood releases in 70mm, even though it was originally filmed in Super 35. According to Wikipedia, in Oslo, Norway, George Lucas’ “Star Wars IV: Special Edition” (1997) premiered in 70mm, but not in the U.S.A. India’s Prasad Studios, based in Chennai, Hyderabad and Mumbai, still releases its major action-musicals on 70mm film, even though they are shot using standard 35mm Arriflex 435/535 cameras.

Even now, large-scale science fiction films like “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977) employ 65mm film stock for visual effects sequences because the film quality does not visibly degrade as much as 35mm when opticals are needed in post-production. Douglas Trumbull, who supervised "CE3K"’s visual effects, maintains that the larger perforations on 65mm film serve better in registering the image, rather than the short-pitch .1866 Bell & Howell standard perforation sizes found in 35mm negative. This use has declined in recent years with the advent of computer-generated images (CGI) and elaborate digital compositing techniques. Although, Sam Raimi’s “Spider-Man 2” (2004) used it for selected visual effects shots and Danny Boyle’s “Sunshine” (2007) for its rear projection process work. 65mm was also used during some of the screen tests on “Superman Returns” (2006), although the movie itself was shot in high-definition using Panavision Genesis cameras. Otti International's Phil Kroll developed the world's first 65/70mm telecine transfer system. This has been used in Hollywood to digitally master various 65/70mm movies. The Phantom 65 is the world's first 65mm digital cinema camera. It has 4K (4096 × 2440) resolution with adjustable aspect ratios, up to 125 fps recording speed, and a depth-of-field comparable to that found with 65mm film photography. The PhantomHD high-definition camera can capture Hi-Def images of 1920 × 1080p or 2K images of 2048 × 1556 resolution and shoot up to 1000 fps.

Todd-AO: Producer, promoter, showman Avram Goldenbogen was born June 22, 1907 in Minneapolis. An original partner of Cinerama, he changed his name to Michael Todd, selling his shares to form the Magna Corporation with movie mogul Joseph M. Schenck. Their 65mm spherical lens (non-squeezed) film process used equipment developed in conjunction with the American Optical Company. Todd-AO’s initial cameras were actually old units from experiments in the 1930s with wide-film. The original Todd-AO ran film at 30 frames-per-second and was supposed to be a single-camera alternative to 3-strip Cinerama. “Oklahoma!” (1955) and "Around the World in 80 Days" (1956) were the first two major motion pictures released in this process. The former was filmed in two formats: one in Todd-AO and the other in Cinemascope. This was because the non-standard 30 fps prevented the manufacture of Cinemascope-compatible 35mm reduction prints. The Todd-AO version of “Oklahoma!” featured alternate wider takes with the actors, and many find it more spirited than the scope version. (It was not filmed simultaneously as in MGM’s earlier “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,” which was released in both scope and flat versions for theatres unwilling to make the change.) In 1994, the original Todd-AO negative was used for the “Oklahoma!” laserdisc. Also, a 30 fps short entitled "The Miracle of Todd-AO" was produced in 1955. Following "South Pacific" (1958), this and all subsequent features were released in standard 24 fps.

In March of ’58, while en route to New York to address the National Association of Theater Owners as “Showman of the Year,” Mike Todd’s private plane—named “The Lucky Liz” after wife Elizabeth Taylor—crashed, killing everyone onboard. In 1960, Nikita Khrushchev and his wife visited the 20th Century-Fox set of “Can-Can.” The Russians had developed a similar system to Todd-AO. It’s ironic that the Cole Porter storyline involves a lawyer (played by Frank Sinatra) who defends a dancer’s right (Shirley MacLaine) to perform daring moves in a Parisian nightclub. Khrushchev was evidently so disgusted by the skimpy costumes, this prompted him to make his famous “We Will Bury You!” statement. Two year’s later, Walter Lang was replaced by Jose Ferrer as director on the Pat Boone bomb “State Fair,” and Todd-AO (which was partly owned by Rodgers & Hammerstein) was replaced as well by Cinemascope. The least known 70mm Todd-AO film was presented at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. Evangelist Billy Graham's Pavilion showcased the film, "Man in the 5th Dimension", daily every hour in several languages. The souvenir booklet announced: “Billy Graham demonstrates the continuity of Christian witness down through ancient and modern times,” and the Reverend’s prologue stated, “You are about to embark on a breathtaking journey through the four-dimensional world of space and time, into the realm of the fifth dimension, the dimension of the spirit…” (but not D-150!). An imported 70mm projection system beamed the “Todd-AO and Technicolor” images onto a wrap-around screen (although dye-transfer prints were never made in 70mm). Ron Fricke’s "Baraka" (1992) became the last film shot in Todd-AO 65mm. Filmed in 24 countries, this National Geographic release detailed the evolution of Mankind and the Earth. Fricke plans to release a sequel entitled "Samsara". It will be the first feature-length film in more than a decade (since Branagh's “Hamlet”) to be shot entirely on 65mm.

KINOPANORAMA: Speaking of Russia, they also had their own version of Cinerama with the film, “Great Is My Country” (1957). In addition to “This Is Cinerama,” Cinerama Releasing Corporation put together a compilation of scenes from a number of Soviet Kinopanorama films, releasing them as “Cinerama’s Russian Adventure” (1966). This debuted in a 70mm composite print with Bing Crosby linking the scenes. It suffered from grain the size of Russian potatoes, possibly due to inferior Soviet film stocks and the extra optical printing stages required. Although available as a 3-strip Cinerama print, only one theatre apparently ever showed it in this format. A Down-Under version shot with an authentic Kinopanorama camera called "Bounty" was supposedly presented as a work-in-progress in 1995, followed by “I Am Australian” in 1998.

THRILLARAMA: A 1956 dual camera/projector process similar to Cinerama.

AVIORAMA: A sideways version of Cinerama by Italian inventor A. Moretti that positioned screens below, in front of, and above the viewer.

TECHNIRAMA: In 1957, Technicolor modified several of its obsolete 3-strip cameras to record horizontal 8-perf VistaVision. Many of these bulky blue cameras were converted to large format 8-perf, incorporating a peculiar half-twist in the film-threading pattern in order to expose the negative 8-perforations horizontally (rather than the standard 4-perf vertical method). A 1.5 reflective lens “squeeze” was added in front of the spherical lens to achieve a 2.35:1 Cinemascope aspect ratio for post-1953 movies. The mirror-prism anamorphic attachment slightly squeezed the image by 50 percent, so that the entire 8-perfs of negative information could be utilized for films released in 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Unlike Cinemascope, the mirror-prism arrangement offered no distortion problems or light loss, but they were quite cumbersome, contributing even more to the Technicolor camera’s weight. The resulting negative was only 10 percent smaller than Todd-AO, so they could even be blown-up to 70mm. In the 50s and 60s, Technirama became the most frequently used wide-film process, from “Escapade in Japan” (1957, featuring Clint Eastwood as a serviceman named Dumbo) to Walt Disney Studio’s forgettable “The Black Cauldron” (1985).

SUPER TECHNIRAMA 70: Technirama’s 70mm releases soon evolved into “Super Technirama 70,” and Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” (1959) became the first 70mm animated feature film release. (It also carries the distinction of being the first Disney traditional cel-animated Blu-ray High-Definition DVD release last October as a special 50th Anniversary Platinum Edition. “Pinocchio” will be the next BD release.) One G-6 labeled camera was used on Stanley Kubrick’s “Spartacus” (1960). The nomenclature refers to the printer lenses used to convert the horizontal 8-perf 1.5 anamorphic squeeze to flat 70mm. Later, this G-6 Technirama camera would be owned by Introvision for shooting VistaVision background plates. (The larger, double-sized negative afforded a copy ratio of 2 to 1, so the front-projected backgrounds exhibited less grain when re-photographed onto standard 35mm 4-perf film.)

| |

CIRCLE VISION 360: While on the subject of Disney, Walt’s 11-projector circular set-up premiered as “Circarama” in July 1955 at Anaheim Disneyland with “Tour of the West.” The show later played at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. The name was changed to Circle-Vision 360 using only nine 35mm cameras and projectors, becoming a permanent fixture in the Tomorrowland portion of the theme park for several decades. It has been utilized at other Disney theme parks, such as Epcot's “O Canada” and “Reflections of China” exhibit, and Paris Disneyland’s Jules Verne attraction, “The Timekeeper,” which features H.G. Wells traveling through time to meet Verne, accompanied by many computer-generated effects. The screens and projectors are arranged above head level, and hand bars are provided for viewers to hold onto or lean against while standing and viewing the films. Circle-Vision 360’s long-running “America the Beautiful” presentation was finally scrapped for the New Tomorrowland facelift, replaced by the waiting-area queue for the now-defunct “Rocket Rods” ride on the old People-Mover track, and then again by the recent “Buzz Lightyear’s Astro Blaster” attraction. Today there are only about ten of these types of cinemas in the world, among them in the United States, Korea, Russia, Japan, France and Taiwan. A Russian version incorporated 22 projectors with two rows of 11 screens positioned above and below the other. CIRCLE VISION 360: While on the subject of Disney, Walt’s 11-projector circular set-up premiered as “Circarama” in July 1955 at Anaheim Disneyland with “Tour of the West.” The show later played at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. The name was changed to Circle-Vision 360 using only nine 35mm cameras and projectors, becoming a permanent fixture in the Tomorrowland portion of the theme park for several decades. It has been utilized at other Disney theme parks, such as Epcot's “O Canada” and “Reflections of China” exhibit, and Paris Disneyland’s Jules Verne attraction, “The Timekeeper,” which features H.G. Wells traveling through time to meet Verne, accompanied by many computer-generated effects. The screens and projectors are arranged above head level, and hand bars are provided for viewers to hold onto or lean against while standing and viewing the films. Circle-Vision 360’s long-running “America the Beautiful” presentation was finally scrapped for the New Tomorrowland facelift, replaced by the waiting-area queue for the now-defunct “Rocket Rods” ride on the old People-Mover track, and then again by the recent “Buzz Lightyear’s Astro Blaster” attraction. Today there are only about ten of these types of cinemas in the world, among them in the United States, Korea, Russia, Japan, France and Taiwan. A Russian version incorporated 22 projectors with two rows of 11 screens positioned above and below the other.

| | QUADRAVISION: Ford Motor Company dabbled in projection as well as cars, displaying a four-projector, quadraphonic sound system in certain shopping malls in 1959.

PANAVISION: A variable prismatic lens developed by Robert E. Gottschalk in 1954 that eventually replaced Cinemascope and is currently the norm. Its unique and highly sophisticated lens design eliminated the distortion problems found in other inferior anamorphic attachments. Directors who had originally complained that the Cinemascope aspect ratio was awkward for shot composition welcomed Panavision’s ability to film close-ups without distortion. In 1962, Panavision developed a de-anamorphozing optical printing lens that enabled labs to blow-up a Panavision 35mm negative to a spherical 70mm release print. The quality proved so successful that filmmakers began substituting this process for their roadshow releases, rather than shooting in the costly 65mm format. Spin-offs for roadshow engagements included Super Panavision 70 (a process in which the movie is shot on 65mm negative with spherical lenses), Panavision 70 (the term originally referred to 70mm release prints using any photographic format, later evolving to mean a 35mm scope blowup to a spherical 70mm release print) and Ultra-Panavision 70 (a 65mm camera incorporating a supplementary lens with a slight 1.25 squeeze ratio to utilize the entire negative area of the 65mm frame). Available exclusively for rental, Panavision insisted that all films photographed with their equipment—whether widescreen or not—be credited as “Filmed In Panavision.” Movies shot with spherical lenses were supposed to use the “Cameras and Lenses by Panavision” credit, but some films contained the wrong wording. This not only confused a lot of people, but made their name synonymous with movies.

MGM CAMERA 65 & ULTRA-PANAVISION 70: The seed for MGM Camera 65 was nurtured in 1954 when the studio decided to remake their 1926 silent classic “Ben-Hur.” Cinerama’s 3-camera configuration was dropped in favor of a single-lens system—a 65mm camera using a modest anamorphic squeeze of 1.33:1 (employing camera negative and print sizes identical to Todd-AO) on a single piece of 65mm film negative. With a projector aperture of 2.21:1, 70mm release prints were made from the 65mm negative and projected onto large screens yielding an aspect ratio of 2.94:1. Ultra-Panavision 70, on the other hand, used a slight anamorphic squeeze of 1.25:1 and camera apertures of 2.072-in. by 0.906-in. (with projector apertures of 1.912-in. x 0.870-in. requiring optical un-squeezing during projection), yielding a screen ratio of 2.76:1. However, Tak Miyagishima of Panavision (who helped create the lenses) and researcher Dan Sherlock maintain that the two processes are one and the same.

In addition, 35mm prints can also be made with a 1.6:1 squeeze in the printer to be compatible with 2:1 squeezed Todd-AO 35 and Panavision 35mm prints (a 1.25 camera squeeze times a 1.6 printer squeeze equals 2:1 total release print squeeze). Delays on “Ben-Hur” prompted MGM to test the new format on “Raintree County” (1957). The studio had planned to release it in 70mm, but apparently all existing theatres were already booked showing “Around the World in 80 Days” in Todd-AO. (The real reason for its less dramatic 35mm release probably owed to the fact that “Raintree County” turned out not to be another “Gone With the Wind,” as the studio had anticipated.) The MGM Camera 65 premiere of “Ben-Hur” arrived on November 14, 1959, referring to the process in advertising as “The Window of the World.” It’s interesting to note that Ultra-Panavision’s first cameras were actually Mitchell FC cameras with 65mm movements instead of the 70mm movements used in the older Grandeur format. The original lenses were nothing more than spherical optics with a pair of anamorphic prisms in front of them. In order to make them soundproof, the cameras had to employ large magnesium blimps weighing in excess of 300 pounds. So, all the ballyhoo over the “new widescreen cameras” proved unwarranted, since they were essentially shot with antique cameras from the thirties. In 1961, MGM sold their cameras to Panavision. Gottschalk refined the lenses and, incorporating his company’s research in cylindrical anamorphics, made them lighter and more portable. MGM rented them back for the remake of “Mutiny on the Bounty” (1962), making it the first film credited as being Filmed in Ultra-Panavision 70! That same year, certain sequences in “How the West Was Won” were shot in Ultra-Panavision where the use of the bulky 3-strip Cinerama camera would have proven difficult. Joe Public was fooled and, needless to say, this helped fuel the fire for single-strip films made with the intention of showing on Cinerama screens.

SUPER PANAVISION 70: This process is identical in every respect to Todd-AO. It’s even similar to Ultra-Panavision 70, except images are photographed through spherical lenses with no squeeze. “The Big Fisherman” (1959) is credited as being filmed in Panavision 70, but is actually the first film produced in Super Panavision 70. The adverts—Panavision 70, Super Panavision, Super Panavision 70 and Panavision Super 70—are, in reality, four names for the same format: the first beginning with “Exodus” in 1960 (although posters proclaimed the contrary), and the last being “Far and Away” in 1992 to show that updated cameras and lenses were used. “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962) was the first film to properly utilize the Super Panavision 70 credit in all its advertising. The roadshow engagement of “2001: A Space Odyssey” opened in this fashion at the Warner Pacific Cinerama Theatre in 1968, which featured box office receipts the size of airline tickets to make patrons feel as if they were taking a voyage into space. It was presented on the curved Cinerama screen without the optical “rectification” for films made in Ultra-Panavision 70 for the Cinerama screen. “Krakatoa, East of Java” (1968) was filmed with Super Panavision cameras and lenses for most photography, and released as a single-film Cinerama presentation at Pacific’s Cinerama Dome Theatre (later re-titled “Volcano” for TV as Krakatoa is actually West of Java).

| |

SMELL-O-VISION: Originally titled, “Scent of Mystery” (1960), this oddity was lensed using 65mm Mitchell cameras similar in principle to Todd-AO, and initially released in 70mm Smell-O-Vision (some critics joked it aptly described the movie as well). The Peter Lorre suspense drama came with various scents—such as perfume and tobacco odors—that served as clues in solving the mystery. Later, it was split into a 3-strip Cinerama print and reissued in a de-odorized format as “Holiday In Spain.” SMELL-O-VISION: Originally titled, “Scent of Mystery” (1960), this oddity was lensed using 65mm Mitchell cameras similar in principle to Todd-AO, and initially released in 70mm Smell-O-Vision (some critics joked it aptly described the movie as well). The Peter Lorre suspense drama came with various scents—such as perfume and tobacco odors—that served as clues in solving the mystery. Later, it was split into a 3-strip Cinerama print and reissued in a de-odorized format as “Holiday In Spain.”

ULTRA CINERAMA: Since sequences shot in Ultra-Panavision 70 were able to fool audiences in “How the West Was Won,” it was thought to adapt that process for single-film movies like “It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” (1963). Near its completion, producer/director Stanley Kramer was approached to premiere it as the first single-lens Cinerama production. Much to his credit, he was quoted as saying: “Mad World was no where near Cinerama,” since the shortest Ultra Panavision focal length lens was 35mm and rarely covered expanses of more than 92 degrees (recall that original 3-strip Cinerama projected images of a 146-degree horizontal viewing angle). The name “Ultra Cinerama” refers to Ultra-Panavision 70 films that have been optically corrected or “rectified” for projection onto curved Cinerama screens, providing a pseudo-Cinerama look so that the side panels of the image are not unnaturally elongated. In “Mad World"’s case, Technicolor un-squeezed the anamorphic image, then starting with zero-squeeze at the center, introduced a gradient compression to the edges of the frame to compensate for the obliquely curved Cinerama screen. (Apparently one reel of “Mad World” was demonstrated to the press as a 3-strip extraction print at Loew’s Cinerama New York in August of 1962.) Other films given this optical rectification include: “The Greatest Story Ever Told” (1965), “The Hallelujah Trail” (1965) and “Khartoum” (1966). Some feel this rectification process may not have helped much in correcting screen distortion since the additional optical steps may have furthered image degradation not found in a regular contact print. That is why spherical films like “2001” made in Super Panavision 70 did not receive this optical correction for the curved screen. John Frankenheimer’s “Grand Prix” (1966) fared even worse since the extreme close-ups of drivers’ helmets were stretched even further by the oblique side-panel screens. Though not an official Cinerama presentation, “Song of Norway” (1970) became one of the last single-strip films showcased in a few Cinerama Theatres. The term “Ultra Cinerama” (used sparingly—and mostly in England) was eventually changed to “Presented In Cinerama” on theatre marquees and advertising.

SUPER CINERAMA: This term refers only to the design of dedicated 3-strip Cinerama Theatres—or ones remodeled to qualify for the Cinerama name—that used a larger floor-to-ceiling screen. It was not a projection process, nor any photographic variation on the 3-strip process (although, “This Is Cinerama” was re-released in a cropped 70mm composite format in 1973). Theater owners often used the term “unofficially” to signify 70mm presentations on a Cinerama screen.

CIRCLORAMA: Leonard Urry set up

Circlorama with Leon Heppner in 1963, a Russian entrepreneur who lived in London for several years. They acquired a bombsite in Denman Street just behind Piccadilly Circus and constructed a building to house the new 360-degree cinema which they had imported from Russia. Eleven screens were arranged around the wall of the circular building. The diameter of the auditorium was 70-ft, serviced by eleven 35mm Philips water-cooled, pulse light projectors housed in an enclosed gallery. The 11 projectors were synchronized to form a continuous 360-degree projected image, and together with a 9-track stereo system, established a “Cinema-In-The-Round” experience.

CINERAMA-360: Also at the 1964 World’s Fair was a Cinerama-360 showing of “To the Moon and Beyond,” sponsored by KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. A moving staircase transported audience members up to an 80-foot dome where astronomical events were sped-up in time via animation, narrated by none-other-than Rod Serling. The show was lensed by Graphic Films in double-frame 65mm.

| |

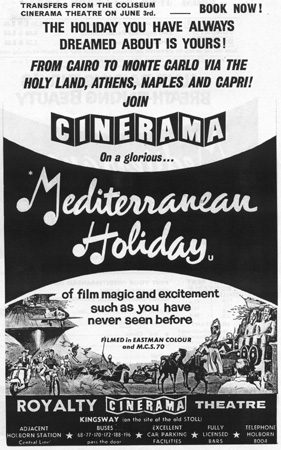

WONDERAMA: Also known as ARC-120, it consists of two rotated 35mm images corresponding to the left and right halves of the picture. Walter Reade-Sterling’s process proved not only futile, but unsuccessful as well. The only Wonderama film, “Mediterranean Holiday,” was later released in Cinerama in 1965 as

“MCS Super Panorama 70” by Modern Cinema Systems, Germany. WONDERAMA: Also known as ARC-120, it consists of two rotated 35mm images corresponding to the left and right halves of the picture. Walter Reade-Sterling’s process proved not only futile, but unsuccessful as well. The only Wonderama film, “Mediterranean Holiday,” was later released in Cinerama in 1965 as

“MCS Super Panorama 70” by Modern Cinema Systems, Germany.

Editors note. MCS' 65mm film "Flying Clipper", filmed in 1962,

was released in the UK and States as “Mediterranean Holiday”.

DIMENSION 150: Essentially Fox’s Todd-AO with a new name and lenses designed by Vetter and Williams. Its nomenclature came from the widest lens, providing a horizontal angle of 150-degrees. Other available lenses exhibited viewing angles of 120, 70 and 50 degrees. In 1966, Fox released John Huston’s heavy-handed adaptation of “The Bible,” though the studio failed to promote the process and it was shown in traditional 70mm cinemas (critics even quipped: “…read the book instead!”). The only other films sporting the

Dimension 150 credit were Franklin Schaffner’s “Patton” (1970) and the short subject “Harmony of Nature and Man.” Despite its abandonment as a production tool, United Artists Theaters replaced existing screens in some of their premiere houses with a deeply curved version, calling it “D-150.” I recall seeing “2001: A Space Odyssey” in 70mm on the Egyptian Hollywood’s D-150 screen before the auditorium was converted by the American Cinematheque for stadium seating. I was one of few in the massive auditorium, freezing because the air conditioner was set too high, which added greatly to the perception of the cold void of space travel.

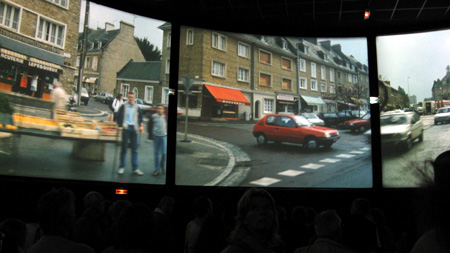

JACQUES TATI’S PLAY-TIME: Jacques Tati continues his fond throwback to the days of silent comedy with Monsieur Hulot trying to keep an appointment amid an antiseptic modern Paris of steel and glass skyscrapers. Tati had grown tired of playing his famous character from “Mr. Hulot’s Holiday” (1953), and in this 2nd-to-last installment, Hulot is often just a small part of the events on screen. In honor of his early endeavors with director Claude Autant-Lara, Tati filmed with a 65mm Mitchell camera and it was presented in France in a non-standard aspect ratio of approximately 1.8:1.

“Play-Time” (1967) is notable for its enormous sets built specially for the film. Art Buchwald provided dialogue for the U.S. edition, cut 47-min. from the original 155-min. French version.

TECHNISCOPE: A system designed to afford a 2.35:1 anamorphic aspect ratio, while utilizing spherical camera lenses and a 35mm camera modified to pull down 2-perforations instead of four-per-frame. Its main purpose was meant to exploit the negative area otherwise wasted in 1.85 (with camera apertures of .868-in. x .373-in.), thereby cutting in half the cost of raw negative footage. Conventional spherical lenses are used (with shorter focal lengths and improved depth-of-field) at standard film speeds of 24 frames-per-second. 2-perf is enjoying a slight resurgence due to the birth of digital intermediate techniques eliminating the need for optical lab work.

SUPER 35: This format is known under a variety of names, such as Super Techniscope, Super 1.85 and Super 2.35. All use flat, spherical lenses as in 1.85 photography. When discussing Super 35, cinematographers usually compose for a 2.35 to 1 aspect ratio, thus requiring an optical step when making dupe negatives for release prints. Super 35 composes for 2.35:1 with standard lenses, extending the width of the frame into the negative normally reserved for the soundtrack, as in shooting full “silent” aperture. Often, directors prefer shooting Super 35 composed for 1.85 (i.e. Super 1.85). Their dubious reasoning is the slight 5 percent increase in negative area will yield a finer-grained image. Tests have shown this to be erroneous. Once the negative has undergone interpositive and internegative optical repositioning, there is virtually no difference between Super 1.85 and standard 1.85 photography. (Better to shoot 3-perf and use less negative, thereby conserving film costs by one-fourth.) It’s often stated there is a production savings in choosing Super 35 over anamorphic. This also is not so, since the expense of optical 35mm dupe negatives needed for release prints negate any cost savings in principal photography. The main reasons for using this format are the less bulky lenses and greater increase in depth-of-field over anamorphic 2.35:1, as James Cameron demonstrated in “Titanic,” with Super 35’s innate potential for keeping both objects in focus simultaneously. The lesser weight and more portable camera packages often omit the hassles found in using anamorphic attachments. This was one of the reasons cinematographer Jeff Kimball chose the format for “Top Gun,” which enabled cameras to fit inside the aircraft cockpits. The format employs lenses which are about half the focal length of anamorphic 2.35, which means Super 35 will have a more expansive, wide-angle look, making distant objects appear further away due to the shorter focal length lenses. Anamorphic’s 2.35 longer lenses tend to have a more “compressed” appearance similar to the effect one gets with a telephoto lens. Advocates of Super 35 claim that it is more compatible with 70mm because it can be enlarged straight to 70, while anamorphic must be un-squeezed first. In actual fact, anamorphic’s greater negative area and finer grain make up for any possible loss in resolution when un-squeezed to 70mm. Also, due to the smaller negative size, cinematographers must limit their choice of camera negatives to slower speed stocks, thereby losing the advantage of high-speed negatives.

| |

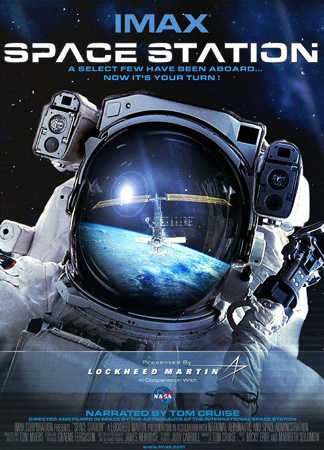

IMAX: This wide-film 65mm process was developed in the early seventies and so far uses the largest film frame in motion picture history—3 times greater than standard 70mm film and 10 times bigger than 35mm. The extra-wide 15-perf frame (2.718-in. x 2.072-in.) increases the information carrying capacity of the film stock, enabling greater detail and resolution to be recorded by the lens. The 70mm film runs horizontally through the projector via a “rolling loop” film movement. Each frame is registered or positioned by fixed registration pins and held firmly against the rear element of the lens by a vacuum. This enables rock steady, jiggle-free projection on screens up to 54-ft high by 70-ft wide, ten times the size of conventional screens. Since dirt or foreign material lodged in the gate magnifies so greatly on the screen, continual air suction must be employed. The 68-percent shutter transmits one-third more lumens than the 50-percent shutter used in conventional projectors. Movies are photographed with wide-angle Hasselblad lenses and projected via Leitz Canada lenses. The octagonal-shaped theatre located in the Museum of Science and Industry in Los Angeles was the very first to feature Imax in THX sound by Lucasfilm. Supposedly, the largest Imax Theatre in the world resides in Prasad’s Multi-Cinema complex in Hyderabad, India. The Dynavision process uses 8-perforations per frame, while the Astrovision system has 10-perfs per frame, utilizing a vertical pull-down to save print costs while being able to project onto an Imax screen. Both are rare, Astrovision occupying Japanese planetariums. Recently, Hollywood has released its blockbusters in an Imax blow-up mode, such as the “Harry Potter” films. Flying sequences in “The Dark Knight” were actually filmed with Imax cameras and projected with regular blown-up footage onto the huge screens. IMAX: This wide-film 65mm process was developed in the early seventies and so far uses the largest film frame in motion picture history—3 times greater than standard 70mm film and 10 times bigger than 35mm. The extra-wide 15-perf frame (2.718-in. x 2.072-in.) increases the information carrying capacity of the film stock, enabling greater detail and resolution to be recorded by the lens. The 70mm film runs horizontally through the projector via a “rolling loop” film movement. Each frame is registered or positioned by fixed registration pins and held firmly against the rear element of the lens by a vacuum. This enables rock steady, jiggle-free projection on screens up to 54-ft high by 70-ft wide, ten times the size of conventional screens. Since dirt or foreign material lodged in the gate magnifies so greatly on the screen, continual air suction must be employed. The 68-percent shutter transmits one-third more lumens than the 50-percent shutter used in conventional projectors. Movies are photographed with wide-angle Hasselblad lenses and projected via Leitz Canada lenses. The octagonal-shaped theatre located in the Museum of Science and Industry in Los Angeles was the very first to feature Imax in THX sound by Lucasfilm. Supposedly, the largest Imax Theatre in the world resides in Prasad’s Multi-Cinema complex in Hyderabad, India. The Dynavision process uses 8-perforations per frame, while the Astrovision system has 10-perfs per frame, utilizing a vertical pull-down to save print costs while being able to project onto an Imax screen. Both are rare, Astrovision occupying Japanese planetariums. Recently, Hollywood has released its blockbusters in an Imax blow-up mode, such as the “Harry Potter” films. Flying sequences in “The Dark Knight” were actually filmed with Imax cameras and projected with regular blown-up footage onto the huge screens.

OMNIMAX: An identical film format to Imax which vignettes the corners of the frame. A 180-degree fisheye lens records the images for later projection onto dome screens over 57-feet in diameter. The fisheye effect is countered by the 180-degree dome curvature. The unusual theatre design limits seating capacity and requires that film be lifted 20-ft out of the projection booth to the film gate overhead. Even though the entire frame of film is unused, the dome effect envelopes the viewer’s field-of-vision, creating a more stimulating experience for some, although screens are typically smaller in square-footage than in normal Imax presentations. Theatres are located in San Diego, Beijing and Hong Kong’s Walkway of the Stars.

INTROVISION: A dual-screen front projection process invented inside a Hollywood garage in 1977 by John Eppolito and myself (patent granted 1988 with a Scientific Technical Achievement Academy Award). The process used the G-6 Technirama camera to photograph background plates onto 8-perf VistaVision for a 2 to 1 copy ratio which decreased the grain when composited onto standard 35mm stock. Actors stood in front of a 60-ft 3-M Scotchlite front projection screen. A VistaVision plate was projected via a quiet Fox Cine-Special camera converted to an 8-perf projector by Geoff Williamson of Wilcam, CA. The normally unused foreground portion of the image that passed through the beam splitter (in this case a 50/50 half-silvered Pancro mirror) was reduced via a plano-concave lens onto a smaller reflex screen. Complementary mattes in front of both the large and small reflex screens enabled actors to appear to pass behind foreground objects in the background plate in one single camera pass.

SHOWSCAN: Doug Trumbull’s 70mm process projects films at 60-frames-per-second, dramatically enhancing the persistence-of-vision that enables us to see moving pictures. The phenomenon of persistence-of-vision deals with the retention of an image on the eye’s retina, so that each picture remains briefly visible after its actual disappearance. Showscan accentuates this effect, further strengthening the illusion of movement, since the rapid succession of still images projected on the screen provides the human eye with more than its share of necessary successive stimuli, thereby enabling sharper images. Originally housed in Trumbull’s old Marina Del Rey Future General headquarters (which later evolved into EEG Studios, and then Boss Film), the impressive visuals combined with huge Ubangi loudspeakers greatly enhanced several exhibits at Vancouver’s 1986 World Expo. It was so clear that many described it as “looking through a window to the world” (a slogan similarly applied to MGM Camera 65). One short film starring Christopher Lee as a mad magician had an actor on film that looked like he was actually behind the screen. Trumbull wanted to introduce Showscan to the public with his production of “Brainstorm” (1983) starring the late Natalie Wood for the sensory-enhanced portions of the film. Unfortunately it proved too costly and the film was released in “Expanding 70” for these sequences (really just Super Panavision 70 with black sidebars extending automatically for the virtual reality segments). A version of Showscan was featured in the Luxor Live triple ride attraction at the Luxor Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas: “In Search of the Obelisk.” This featured a gimbaled people-moving mechanism in front of an 8-perf 35mm projected image at 48 fps, a runaway elevator during the pre-show, plus the actual 70mm 60 fps Showscan talk-show format in which the audience thought they were watching actual live characters from the ride-film.

| |

IMAX 3-D: The first 3-D Imax short debuted at Vancouver’s Expo ’86 using two huge Imax projectors combined with the appropriate polarization filters which corresponded with the glasses worn by audience members. The 3-D Imax at Edwards Cinemas in Orange County, California was the first to introduce surround-sound goggles dubbed PSE (Personal Surround Experience), beginning with the first 3-D Imax story-themed film, “Wings of Courage,” directed, written, photographed, designed, ad nausea by Jean-Jacques Annaud. This 3-D alternating shutter-synchronized technique was later abandoned due to the uncomfortable helmet in favor of a traditional polarized three-dimensional process. Even 3-D films are being shown in the 70mm Imax format. Robert Zemeckis’ “Polar Express” (2004) in Imax 3-D earned 14 times as much per screen as the simultaneous 2-D 35mm release. James Cameron and Vince Pace developed the Fusion Camera System (aka Reality Camera System 1) as way to shoot features in 3-D. The digital high definition camera was used on Cameron’s documentaries “Aliens of the Deep” and “Ghosts of the Abyss.” Robert Rodriguez also used the camera to shoot “Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over” (2003) and “The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D” (2007). IMAX 3-D: The first 3-D Imax short debuted at Vancouver’s Expo ’86 using two huge Imax projectors combined with the appropriate polarization filters which corresponded with the glasses worn by audience members. The 3-D Imax at Edwards Cinemas in Orange County, California was the first to introduce surround-sound goggles dubbed PSE (Personal Surround Experience), beginning with the first 3-D Imax story-themed film, “Wings of Courage,” directed, written, photographed, designed, ad nausea by Jean-Jacques Annaud. This 3-D alternating shutter-synchronized technique was later abandoned due to the uncomfortable helmet in favor of a traditional polarized three-dimensional process. Even 3-D films are being shown in the 70mm Imax format. Robert Zemeckis’ “Polar Express” (2004) in Imax 3-D earned 14 times as much per screen as the simultaneous 2-D 35mm release. James Cameron and Vince Pace developed the Fusion Camera System (aka Reality Camera System 1) as way to shoot features in 3-D. The digital high definition camera was used on Cameron’s documentaries “Aliens of the Deep” and “Ghosts of the Abyss.” Robert Rodriguez also used the camera to shoot “Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over” (2003) and “The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D” (2007).

MULTI-SCREEN: As many as ten 35mm projectors gave a veritable ballet of images on ten screens of different sizes, including one that was spherical. Created by the Canadian Museum of Civilizations in Ottawa for its premiere presentation at Vancouver’s Expo ’86, the didactic spectacle traced the history of human communications.

STAR TOURS: The original Disneyland debuted this ride in its New Tomorrowland section of theme park, replacing Monsanto’s dated “Adventure Though Inner Space.” It is one of the first motion simulator rides to move the entire audience as one, rather than in individual seats. Star Tours first saw light as an attraction based on Disney’s 1979 debacle, “The Black Hole.” It set out to be an interactive simulator attraction where riders could choose the car's route. After preliminary planning, the Black Hole Ride was shelved due to its enormous cost—approximately $50 million—as well as the poor box office of the film itself. Instead of completely dismissing the idea, Disney decided to make use of its partnership with George Lucas which began in 1986 on the 3-D “Captain EO” Michael Jackson attraction. Disney’s Imagineers purchased four large military flight simulators at a cost of $500,000 each and designed the ride structure. Meanwhile, Lucas and his team of visual effects technicians worked on the first-person perspective film that would be projected inside the simulators. A mechanical R2 droid robot served as pilot for the audience. On January 9, 1987, at a cost of $32 million (nearly twice that of the entire park in 1955), the ride opened to throngs of patrons, many of whom dressed as “Star Wars” characters for the occasion. In celebration, Disneyland remained open for a special 60-hour marathon from 10am Jan. 9 to 10pm Jan. 11. The Grand Opening was officiated by Lucas, C3PO, R2D2 and Michael Eisner of Disney Studios.

THE MAGIC CARPET: A double Imax system projected onto two screens: one vertical, the other horizontal, each covering 700 square meters. The images fly past underneath the audience’s feet, making them feel like they are “floating” on a glass floor. This process is exclusively found in France’s Futuroscope Park just outside Portiers. The film “Des Fleurs dans le Ciel” (Flowers in the Sky) takes viewers on a 3000-kilometer journey following the life cycle of Monarch butterflies as they migrate to Mexico for the winter.

KINEMAX: The first Imax cinema in France debuted at Futuroscope Park, projecting images onto the largest flat screen in Europe (600-m). The peculiarity of this system over that of other Imax theatres is that the screen is raised at the end of the performance to let the audience out.

CIRCULAR CINEMA: This process was installed by the American firm Iwerks and consists of nine interlocked 35mm projectors and nine screens. The projection surface is 312-m and an electronic control system synchronizes the nine films which are blended together in a process similar to Cinerama. Iwerks typically relies on either 35mm film or video projection.

DYNAMIC MOTION SIMULATOR: Slaved to the image by a computerized system designed by the Swiss company Intamin, the hydraulically-actuated seats simulate the action of the film. When combined with the 60-frames-per-second Showscan process developed by Trumbull, this flight simulator allows for some astonishing physical sensations as the retina is saturated by a flood of images. The filmed sequences—typically roller coaster rides, runaway trains, downhill skiing—rely on a sensation of speed in order to create a feeling of vertigo for the viewer.

CINEAUTOMATE: An interactive film in which the audience can influence the plot at a number of points. Each spectator votes from his or her chair using an electronic device. As many as eight scenarios are proposed. One of the first interactive films from the Czech filmmaker Raduz Cincera, “La Vieil Arbre et les Enfants” (The Children and the Old Tree), tells the story of four children accompanied by a pair of adults who use a thousand and one tricks to prevent the destruction of an old tree.

8-PERF 65MM: Developed by inventor Jan Jacobson of Augsburg, Germany (creator of the first Imax camera and the Nielson-Hordell dual-screen front-projection system), this vertical film format was used for amusement park motion-simulator ride-films by Iwerks, such as 1995’s “Aliens: Ride at the Speed of Fright” at Pier 39 in San Francisco. Directed by Stuart Gordon of “Re-Animator” fame, this became one of the last ride-films to utilize miniatures photographed in 8-perf VistaVision by Paul Gentry (with motion-control snorkel-lens programming by Les Paul Robley) before being replaced exclusively by computer-generated digital images. As many as 22 separate stepper motors were motion-controlled, ranging from first-person camera movements, to opening gates and debris, to interactive DAC lighting for when the vehicle scraped against metal, to a roving searchlight atop the APC. An Iwerks programmer synchronized the movement of the simulator with the apparent movement of the motion-controlled Armored Personnel Carrier’s first-person perspective from the “Aliens” movie. Moves could then be altered in case the simulator’s hydraulics could not reset in time. The cool thing about 8-perf 65mm is that it possesses nearly the same aspect ratio as Imax’s horizontal image, using a camera aperture of 2.072-in. by 1.449-in. This means it can be blown-up to Imax with negligible loss in image quality, thus saving half of the production’s 65mm negative costs!