Dream Journeys: The M.C.S.-70 Process and European Cinema of the 1960s |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Christian Appelt, Germany | Date: 04.01.2009 |

Chapter 1: Dream Journeys Across the Triptych Screen |

|

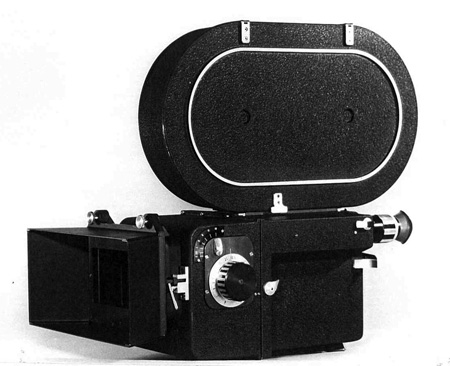

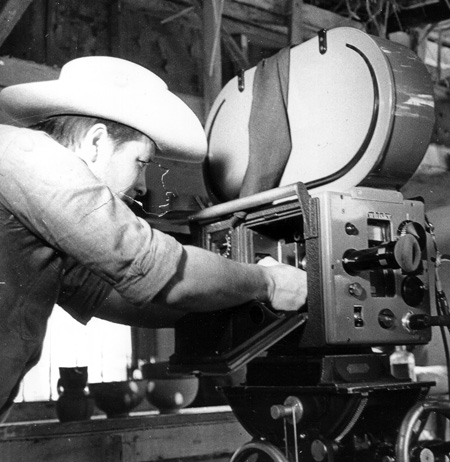

Special MCS 70 camera

for MGM made by Jan Jacobsen. Image Gerhard Fromm Collection Special MCS 70 camera

for MGM made by Jan Jacobsen. Image Gerhard Fromm CollectionAt the start of it all was the three-strip Cinerama process, which, since 1952’s "This is CINERAMA", had been thrilling cinema audiences with spectacular travel shots from all around the world. The panoramic projection, with its deep-focus, high resolution and all-around vision-effect, and the full-range seven-track magnetic sound, treated the public to a far more intense cinematic experience than had been possible with the standard 1:1.37 Academy format. And the new formats which would be, in the years that followed, unleashed on film-makers, cinema operators and the cinema-going public tried more or less closely to imitate the immersive effect of Cinerama, while choosing not to adopt the three-strip method of filming and projection. CinemaScope was known as »the poor man’s Cinerama«, able as it was to be used on the basis of the already-current 35mm technology – although the phrase is a misnomer insofar as this process, too, demanded investment in new screens and sound techniques and significant expenditure in adapting it to existing manners of production. During the whole of the 1950’s, Cinerama continued to produce travelogue after travelogue, and these continued to find an audience. However, negotiations with established studios and film producers about feature films in the three-strip format dragged on and on until 1961, when MGM finally gave the green light, with "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm" (1962) and "How the West Was Won" (1962) for Cinerama feature film production. |

More

in 70mm reading: MCS 70 - Superpanorama films Traumreisen auf breitem Filmband: Das M.C.S.-70-Verfahren MCS 70 Field Camera The Work of Jan Jacobsen Robert Gaffney, cinematographer Notes about the filming of "Motion" and "Sky over Holland" Bob Gaffney, "Motion", "Sky over Holland" Conversations with Olivier Brunet, "Fanny's Wedding" "The making of" Tanakh Bibelen al-Quran Internet link: First published in Todd-AO festival program, October 2008 Bundesarchiv |

The Todd-AO system introduced in 1955 was unable, indeed,

to quite match

the »participation effect« of Cinerama. But it certainly was a less

complex, yet high quality process – exactly the goal Mike Todd had set

for himself with his famous call for »Cinerama out of one hole«. There was no

longer any need for that complete reconstruction of cinema auditoriums

which had been required to accommodate the deeply-curved Cinerama

screen. And instead of Cinerama’s threefold projection technique,

requiring correspondently large numbers of staff, Todd-AO’s huge screen

was served by just a single DP70 universal projector, specially

developed by Philips for the Todd-AO format but compatible with all

existing sound- and image-recording processes back through most of the history of the 35mm format. In the confusion of different widescreen

systems proliferating in the 1950’s, this was a powerful argument in favour

of Todd-AO for cinema owners, so that 70mm as a premium exhibition

format was in a very short time firmly established on the cinema

landscape. The Todd-AO system introduced in 1955 was unable, indeed,

to quite match

the »participation effect« of Cinerama. But it certainly was a less

complex, yet high quality process – exactly the goal Mike Todd had set

for himself with his famous call for »Cinerama out of one hole«. There was no

longer any need for that complete reconstruction of cinema auditoriums

which had been required to accommodate the deeply-curved Cinerama

screen. And instead of Cinerama’s threefold projection technique,

requiring correspondently large numbers of staff, Todd-AO’s huge screen

was served by just a single DP70 universal projector, specially

developed by Philips for the Todd-AO format but compatible with all

existing sound- and image-recording processes back through most of the history of the 35mm format. In the confusion of different widescreen

systems proliferating in the 1950’s, this was a powerful argument in favour

of Todd-AO for cinema owners, so that 70mm as a premium exhibition

format was in a very short time firmly established on the cinema

landscape. The only attempt to compete with Cinerama on the specific technological terrain it had made its own (3 strips of film) occurred in 1957, when the cinema chain National Theatres Inc., together with the Smith-Dietrich Co., introduced a widescreen process which also worked with three strips of film and which they designated "Cinemiracle". Certain technical variations were aimed at making the dividing lines between the three individual panels of the three-part panorama image less noticeable to the audience than they were in Cinerama projections. The only film ever shot in Cinemiracle was "Windjammer" – a travelogue, of course, produced by Louis de Rochemont III., who had already come to attention as producer of the earliest Cinerama films. After "Windjammer"; Cinemiracle was simply bought up by Cinerama Inc. Three-strip film production ended after "How the West Was Won", with a general move to single-strip processes based on the 70mm format (Ultra Panavision, Todd-AO, Super Panavision). This meant a sacrificing of the impressive »depth effect« of the former processes – finding supreme expression in Cinerama’s unique »participation effect« – in favour of traditional shooting techniques which were more compatible with the 35mm presentation dominant, then and now, on the market. Interestingly enough, despite the great success of Cinerama, it took quite some time before films in this format could also be seen in Germany. "This is Cinerama" (1952) received its European première some seven years later, namely on 29th of April 1959 in Berlin’s Capitol Theater. The Cinemiracle production "Windjammer" had, by this time, been showing in Germany since 15th of July 1958 (première in Munich’s Royal-Palast). It is also in Munich that there begins the M.C.S. story – with a quotation from the cinema industry periodical Film-Echo/Filmwoche: |

|

»It was in order to make it technically possible to present Cinemiracle

films in Germany that the company Modern Cinema Systems K.G. (M.C.S.-Film

K.G.) was established in Munich (at Türkenstrasse 89). It was also this

company that arranged the loaning-out of the necessary projection

equipment to Munich’s Royal-Filmpalast. The Royal thereby became the

first cinema in Germany to receive a Cinemiracle projection system – and

this only shortly after the first Todd-AO system in Germany also had

been installed in this very theatre.« »It was in order to make it technically possible to present Cinemiracle

films in Germany that the company Modern Cinema Systems K.G. (M.C.S.-Film

K.G.) was established in Munich (at Türkenstrasse 89). It was also this

company that arranged the loaning-out of the necessary projection

equipment to Munich’s Royal-Filmpalast. The Royal thereby became the

first cinema in Germany to receive a Cinemiracle projection system – and

this only shortly after the first Todd-AO system in Germany also had

been installed in this very theatre.« |

|

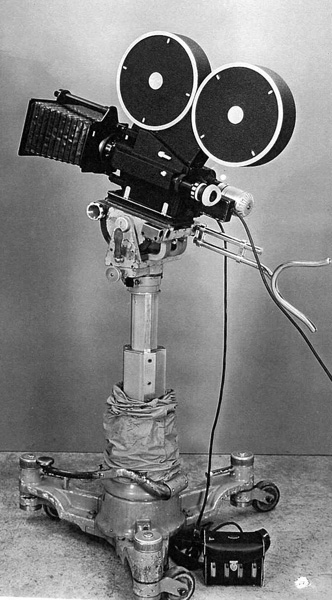

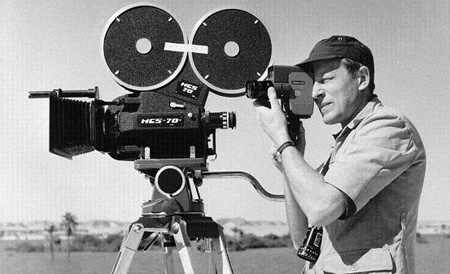

MCS 70 field camera and Heinz Hölscher.

Image Heinz Höelscher Collection MCS 70 field camera and Heinz Hölscher.

Image Heinz Höelscher CollectionIn the material about the film released to the German press, the company presented itself under the title »M.C.S Film Distributors«. The German presentation of "Windjammer" proved, moreover, to be a great success. In Berlin alone over 400,000 people went to see the film in its first 30 weeks. In Essen, it was over 370,000. |

|

Chapter 2: The Inventor |

|

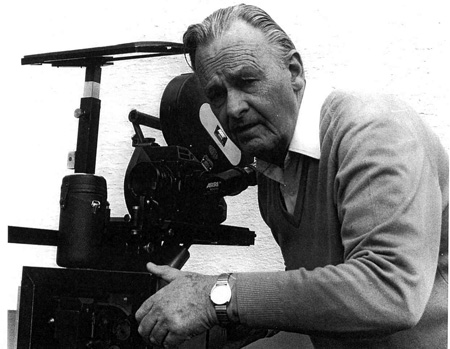

Jan Jacobsen in his work shop. Image Gerhard Fromm Collection Jan Jacobsen in his work shop. Image Gerhard Fromm CollectionAt the beginning of the 1960’s, after a decade of dramatic developments in film technology, the storm of innovation began finally to subside somewhat. Besides the internationally standardized CinemaScope anamorphic process (2.35:1) and the spherical matted widescreen formats (1.66:1 and 1.85:1), use continued to be made of the classic Academy format (1.37:1) After "One Eyed Jacks" in 1961, VistaVision disappeared as a production format. In the United States, MGM finally produced, in cooperation with Cinerama, two feature films in three-strip format and these enjoyed successful runs in cinemas. No further »true« Cinerama productions were, however, undertaken after these. |

|

Jan

Jacobsen with his "Dual screen-front projection" for VistaVision format.

Image by Gerhard Fromm Collection Jan

Jacobsen with his "Dual screen-front projection" for VistaVision format.

Image by Gerhard Fromm CollectionSince by this time a large number of European cinemas had been equipped to present 70mm films, and since European producers were, for economic reasons, increasingly interested in elaborate cinematic co-productions, there seemed indeed to exist a real need for a European wide film process. It was a happy chance, then, that brought together, just at this point, the Modern Cinema Systems company and an inventor and film technician of special genius. The Norwegian Jan W. Jacobsen (1916-1998) had already developed various anamorphic camera lenses designed for the filming of CinemaScope films, including the UltraScope system marketed by Arnold & Richter and used in the filming of a large number of Karl May and Edgar Wallace films. Jacobsen had also built an experimental Technirama camera with horizontal 8-perf movement, as well as various other 65mm cameras designed for use in various 65/70mm processes He was also the one to familiarize the IMAX Corporation with the »Rolling Loop« mechanism of film transport [invented by Ron Jones, Australia, ed] – still used by IMAX today – without which projection of IMAX’s massive 15-perforation 70mm strips of film would simply not have been possible. Besides undertaking various specific commissions – such as building a compact 65mm camera for MGM – Jacobsen was constantly working on new ideas which would make the work of film-makers easier and the experience of cinema-goers more intense. The film technician and film historian Gerhard Fromm tells of how the M C S system arose as a variation on the successful Todd-AO process: |

|

»At the time Jan was trying to invent something he called the ›Dynamic

Frame‹ for use in 70mm, in which the movable screen masking was used to

enlarge or reduce the image size, depending on whether just individual

people were to be seen on screen, or a whole panoramic image. He did some

experiments with a little 65/70mm camera he had built himself and

needed, of course, somewhere to look at his own test footage. He went to

[Rudolf] Englberth (who ran the Royal Filmpalast). He looked at the

footage a few times together with Jan and finally he said: "Look here, Jacobsen,

don’t waste your time with these games anymore. Why don’t you just get

down to it and build us a German 70mm camera?"– Then he got [Rudolf] Travnicek involved in the discussions. He was married to [the actress]

Hannelore Bollmann and had some ambitions in the area of film

production. Travnicek had made a heap of money representing Caterpillar

at the time, and he financed the whole thing.« »At the time Jan was trying to invent something he called the ›Dynamic

Frame‹ for use in 70mm, in which the movable screen masking was used to

enlarge or reduce the image size, depending on whether just individual

people were to be seen on screen, or a whole panoramic image. He did some

experiments with a little 65/70mm camera he had built himself and

needed, of course, somewhere to look at his own test footage. He went to

[Rudolf] Englberth (who ran the Royal Filmpalast). He looked at the

footage a few times together with Jan and finally he said: "Look here, Jacobsen,

don’t waste your time with these games anymore. Why don’t you just get

down to it and build us a German 70mm camera?"– Then he got [Rudolf] Travnicek involved in the discussions. He was married to [the actress]

Hannelore Bollmann and had some ambitions in the area of film

production. Travnicek had made a heap of money representing Caterpillar

at the time, and he financed the whole thing.« |

|

Filming "Uncle Tom's Cabin". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Filming "Uncle Tom's Cabin". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionAt this time, the market for European productions which could only be marketed within their respective country - or the linguistic region of their production - was becoming smaller, and many producers saw the only solution as lying in co-productions in which stars and financing were divided up across several countries and production firms. The 70mm format, with its extremely sharp, detailed and clear image, appeared to be an ideal medium for films with globally marketable themes and impressive viewing values. The problem was that there existed no independent European 65/70mm technology. All that was available was American camera systems, the high rental and licensing costs, which European producers were either unable or unwilling to bear. Only Technicolor’s Technirama process, based on VistaVision with double-frame 35mm film running horizontally, had been able to establish itself in Europe as a high-quality large-format system. For Technirama processing and printing, however, the producer remained dependent on the Technicolor film labs in Rome or London. Great hopes were placed in the 65/70mm format. The European film industry had adopted the view that »the best form of defence is attack«: Film producers hoped to break out of the situation of fragmented nation-by-nation productions and into the arena of multi-national large-scale productions, in order to have once again something to compete with the dominant US film industry. There was consequently definitely a demand for a European 65/70mm shooting process which, on the projection side, would be compatible with the already-successful Todd-AO system. The first device to emerge from Jan Jacobsen’s drawing board was the M.C.S. Field Camera, a compact, high-precision piece of equipment which weighed only about 12 kilograms. It was no hand-held camera, but still significantly lighter than the massive Mitchell apparatuses which were usually used in Todd-AO and Super Panavision production. Jacobsen selected high-quality lenses originally designed for medium-format still photography which easily covered the 65mm-format camera film gate without vignetting. Later, there was added a 17mm wide-angle lens newly developed by Jacobsen, which permitted shots similar to those 128 degree wide shots made with the famous Todd-AO »Bugeye« lens, but which was so small that it could be used without difficulty in action shootings of all types. The Field Camera was able to accommodate magazines for either 500 or 1000 feet of film, so shooting-times of up to 8 minutes were possible without mag-change. The maximum speed was 40 frames a second and both a synchronous motor and a variable speed motor were available. |

|

Filming "Uncle Tom's Cabin". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Filming "Uncle Tom's Cabin". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionFilm professionals were especially impressed by the compact rotating mirror reflex viewfinder, which showed with absolute precision the image that was about to be shot. Many other wide-film and large-format cameras were equipped only with »rack-over« finders, or with parallax-corrected side-attached viewfinders which allowed less than perfect control of framing and no control at all of focussing at all while the camera was running. The comparatively light Field Cameras were, in many shooting situations, superior to the more massive American 65mm cameras, and the high-precision claw movement and optical system which Jacobsen had designed meant there was absolutely no problem intercutting with scenes which had already been shot using other 65mm processes. As an interim solution for synchronous sound shooting there was a simple blimp housing, in order to dampen down the running noise of the Field Camera (more or less comparable to that of a 35mm Arriflex IIB). The thus-blimped cameras, however, proved awkward to operate, which led to the blimp housing’s being used only sporadically. Jan Jacobsen, meanwhile, was working on the »self-silenced« M.C.S. Studio Camera, which was first tried out on certain scenes in "Uncle Tom's Cabin", and was finally applied as the regular main camera in "Congress of Love". The movement of the Studio Camera was identical with that of the Field Camera, the only difference being that the padded housing allowed it to operate almost noiselessly. Three such M.C.S. Studio Cameras were built in all. Almost all the films made in M.C.S.-70 were multinational co-productions in which the actors, originating from different countries, either played their roles in their own languages or spoke a accented English unacceptable for direct use. For this reason, the films were usually dubbed, another reason to prefer the more mobile Field Camera. Only rarely, as for example on "Savage Pampas", was a film produced throughout with original (English) dialogue and sound and using the Studio Cameras. |

|

Chapter 3: Around The Mediterranean |

|

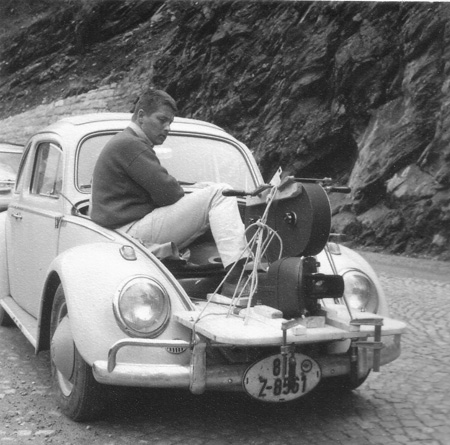

Mr. Dieter Gaebler on a VW filming "Flying Clipper". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Mr. Dieter Gaebler on a VW filming "Flying Clipper". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionIn the years 1961/62, images from distant countries with an exotic charm were still something for which the cinema-goer was willing to shell out money at the box office. Already with Cinerama, the widescreen cinema experience afforded many Americans a kind of virtual presence at all the wonders of the world - before mass international tourism would be able to offer them a real presence there: "This is Cinerama" made, as it were, a perfunctory stop at every item on the compulsory itinerary of an all-inclusive »Europe-In-6-Days« tour: Rome, Venice, Vienna – with the obligatory Verdi opera, audience with the Pope or a few bars from the Vienna Boys’ Choir thrown in at each respective halt on the journey. Films about foreign lands and exotic cultures, such as Hans Domnick’s two-part travel film "Traumreise Der Welt" ("Dream Road of the World") (not distributed in the US) drew crowds of people into the cinema in Europe. In producing a travel film, M.C.S. would require no expenditure on stars but the format would offer a whole range of opportunities to demonstrate the new 70mm camera system not only to the public but also to other producers and film-makers in the most spectacular manner. Such a film was announced under the working title "Windjammer - Part 2", a name by means of which M.C.S. was clearly aiming to exploit the success of the earlier Cinemiracle film. Cinemiracle Productions Inc. were naturally less than pleased with this manoeuvre and began legal proceedings against the Munich firm. |

|

|

Flying Clipper Has Its Wings Clipped In England »The American firm Cinemiracle International Pictures Inc. has succeeded, in London, in winning a court injunction – enjoying legal force up until 2nd October 1962 – preventing the MCS Film Company, Munich, and Rudolf Travnicek from continuing to produce, print or publicly present the film "Flying Clipper". This injunction will prevent, above all, any further processing and printing work on the film at Technicolor in London. Cinemiracle, a subsidiary of Cinerama Inc., accuses Rudolf Travnicek of having breached, with his project "Flying Clipper", certain contractual agreements which he had entered into some years ago on taking over the film "Windjammer".« (Film-Echo/Filmwoche 70/1962, p. 5) |

|

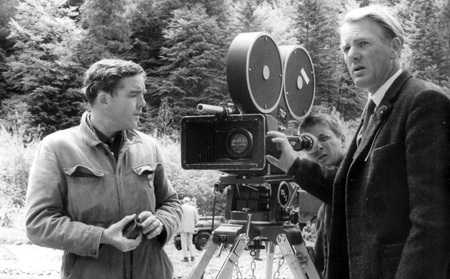

Bob Gaffney filming "Fortress of Peace". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Bob Gaffney filming "Fortress of Peace". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionA short time later, the parties to the dispute were able to reach a settlement. M.C.S. changed the German title to "Flying Clipper - Traumreisen Unter Weissen Segelen" and yielded the US distribution rights for the film to Cinemiracle, or rather to National Theatres Inc. In English-speaking countries, M.C.S’s Traumreise, or »dream journey«, was shown under the title "Mediterranean Holiday". Burl Ives did the voice-over commentary for the English version and sang »Ballads to the Sea«. Jacobsen’s Field Camera, six of which were used in the shooting of the film at a whole series of different locations, proved to be robust and reliable. The most was made of every possible movement effect. The camera accompanied a ladies’ motor scooter club along the winding coastal roads of Dalmatia, went shooting along concrete runways mounted on go-karts, and captured, strapped below the fuselage of a Dornier Do27 plane, a whole series of astonishing aerial shots. It is, above all, these aerial images, shot by Heinz Hölscher, that make the film still worth seeing even today, because they form records of landscapes in the Mediterranean area which, due to new house- and road-construction and also due to mass tourism, are today altered almost beyond recognition. A rather pompous voice-over commentary links the various episodes, spoken by German actor Hans Clarin who had already provided the narration for "Windjammer". And indeed, the parallels to the first film are more than coincidental. The Norwegian cadets of the »Christian Radich« had paid a visit to a US aircraft carrier – which must also, of course, be admired by the crew of the »Flying Clipper«. "Flying Clipper" was not made with synchronous sound. The few passages of dialogue were post-dubbed. On some takes, for example those in the Egyptian »Valley of the Kings«, Jan Jacobsen’s ultra-light 65mm handmade prototype camera was used again. Moreover, this was a journey from which one of the Field Cameras was destined to never return. It fell overboard and must be assumed to be lying on the bed of the Mediterranean to this very day – a confirmation, at least, of the wisdom of having secured proper equipment insurance. |

|

Chapter 4: Tying Up The Package |

|

Dieter Gaebler working with

a blimped ARRI 35mm camera. Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Dieter Gaebler working with

a blimped ARRI 35mm camera. Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection"Flying Clipper" not only enjoyed a certain success with the public but also served beyond a doubt to demonstrate the merits of the new process. The next step, then, would be to secure for producers a package that would meet all their technical needs as regards large-format film production. In Germany there were at the time, as indeed there still are not, any facilities for 65mm processing and 70mm release printing, since no film lab was willing to make the additional investments required. The processing and printing work for "Flying Clipper" (Eastman Color negative and positive stock) was consequently done at Technicolor Ltd. in London, where facilities were available for the processing and optical conversion of all types of non-standard film formats. Later M.C.S. productions were processed on the continent. A cooperative alliance of several French film labs and sound studios offered, under the name »Les Laboratoires Français« and the trademark SUPER PANORAMA, all services necessary for the processing of large-format film. And, later, Fotofilm S.A. in Madrid also offered 65mm processing and 70mm release printing and magnetic striping. From the processed camera negative the lab produced, by optical reduction, 35mm rushes in CinemaScope format which then served for editing and postproduction work. Finally, the 65mm negative was cut according to the work print. The final colour grading was effected by means of test strip printing. For selected large cinemas, 70mm release prints (2.21:1) were produced by contact printing from the original camera negative. For the normal 35mm theatres the large-format image was reduced via an intermediate negative, adding 2x horizontal compression and slight cropping to get standard 35mm 2.35:1 Scope release prints. |

|

|

Whoever rented the M.C.S. system for one of their productions did not

just get the cameras. They also got a whole team of experienced camera

technicians and assistants who not only knew the technology invented by

Jacobsen down to its last nut and bolt but were also capable, following

the instructions of the respective director of photography, of shooting

second-unit material on their own responsibility. The first feature films to be made with the system were the fairy tale movie "Shéhérazade" (F/I/E 1963), the cloak-and-dagger story "La Tulipe Noire" (F/I/E 1963) and the »Euro-Western«, inspired by the novels of Karl May, "Old Shatterhand" (BRD/F/I 1963/64). Meanwhile, M.C.S.-Film had brought on board the music and film producer Aldo von Pinelli, who financed the making of the next few of the company’s own film productions. Pinelli had not only been, since the 1930’s, a screenplay author and song lyricist very much in demand. He had also, through his company Melodie-Film, produced musical films with Freddy Quinn, and also the dramatic film "Madeleine Und Der Legionär" (1954) directed by Wolfgang Staudte. The actual direct supervision of the M.C.S. productions was a task taken on by Georg M. Reuther, who had already acquired some experience in co-productions. The view that was generally taken at this time of the prospects and possibilities of the German cinema film is clearly illustrated by this extract from an interview with Aldo von Pinelli: »I am of the view that small-scale German films really have no chance of success any more and will not be able, either at home or abroad, to survive the competition that is now emerging from television. This means that we have no choice but to begin to operate on a much bigger scale and to set about making films that are interesting in every respect. [...] The 70mm process is one that succeeds excellently in doing justice to the essential breadth of film and to the sheer magnitude of the locations in which its stories are played out. By giving expression to this essential breadth of film, it gets across an impression which is beyond anything that TV will ever be able to offer.« |

|

70mm frame blow-up from "Der Kongress Amüsiert Sich". Image from Schauburg Kino. 70mm frame blow-up from "Der Kongress Amüsiert Sich". Image from Schauburg Kino."Uncle Tom's Cabin" (BRD/I/YU 1965) was just such an attempt to produce, by means of the pooling of European resources, something that could be set against the overwhelming force of American cinema. This story – famously one set in the American South – was filmed for the most part in Yugoslavia, the locations provided by which generally make, here, a more convincing impression than does the »Balkan Wild West« offered by the Karl May films. The film was directed by Géza von Radvanyi, who, besides all sorts of routine journeyman jobs, had also been responsible for the artistically successful remake of "Mädchen in Uniform" (BRD/F 1958). The 70mm cinematography was in the safe hands of Heinz Hölscher, thanks to whose carefully considered forming of light and image the film displays shots of a remarkable spatial depth and plasticity which need fear no comparison with the effects achieved by the American Todd-AO system. The concentrated, understated performances by Herbert Lom and O. W. Fischer also speak strongly in the film’s favour. The generally positive impression that the film still makes is compromised, admittedly, by the uninspired, clumsily melodramatic music of Peter Thomas, which sounds downright weird to an audience experiencing the film today. The producer Pinelli seems not to have been fully aware of how far pop-style musical arrangements, and choral interludes (that displayed with grotesque unmistakably all the signs of studio recordings), must inevitably harm the quality of a dramatic film. Interestingly enough, "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was marketed in the USA in highly sensationalist manner as an exploitation movie, and repeatedly cut in the course of time, to a point where some versions ran only 78 minutes. |

|

The next film produced by Pinelli, "Congress Of Love" (1966), likewise

attempted to appeal to as many different strata as possible of the

cinema-going public by a combination of the most various stylistic

elements – some of which proved to be not so smoothly combinable. It

should be mentioned again here that the 1960’s were a period in which

great uncertainty and anxiety reigned among film producers regarding

what the public actually wanted to see in cinemas. A part of the public

was simply turning away from the cinema altogether, its role of

day-to-day entertainment being increasingly taken over by television,

while the tastes of a younger and more aesthetically demanding audience

seemed, as yet, difficult to calculate. It seemed that the once reliable

recipes and genres of the past could no longer be trusted, so that the

attempt was undertaken to produce something that looked like standing a

chance of being acceptable to everyone: a combination of traditional

narrative cinema with »sure-fire« stories meeting international

standards, spiced up wherever possible with a few set pieces oriented

specifically to the youth market. This appeared at the time to be a

viable solution. The next film produced by Pinelli, "Congress Of Love" (1966), likewise

attempted to appeal to as many different strata as possible of the

cinema-going public by a combination of the most various stylistic

elements – some of which proved to be not so smoothly combinable. It

should be mentioned again here that the 1960’s were a period in which

great uncertainty and anxiety reigned among film producers regarding

what the public actually wanted to see in cinemas. A part of the public

was simply turning away from the cinema altogether, its role of

day-to-day entertainment being increasingly taken over by television,

while the tastes of a younger and more aesthetically demanding audience

seemed, as yet, difficult to calculate. It seemed that the once reliable

recipes and genres of the past could no longer be trusted, so that the

attempt was undertaken to produce something that looked like standing a

chance of being acceptable to everyone: a combination of traditional

narrative cinema with »sure-fire« stories meeting international

standards, spiced up wherever possible with a few set pieces oriented

specifically to the youth market. This appeared at the time to be a

viable solution.This complex combination of intentions is also perceptible in "Congress of Love", whose »framing story« in the wax museum provides the film with a certain ironic distance from historical and costume dramas of the traditional type and also permits, as if purely incidentally, the director to take his audience on that roller-coaster ride which had become almost obligatory since the introduction of Cinerama and Todd-AO. At the same time, the choice of theme and the leading actors clearly indicate the film to be one intended to attract a public provenly appreciative of such a »better class« of cinema entertainment as "Katja, die Ungekrönte Kaiserin" (F 1959) or "Das Glas Waser" (BRD 1960). It is an intriguing question whether Aldo von Pinelli would have continued even in the later 1960’s to produce further stories in 70mm, and how exactly he would have gone about it – but this is something we will never know. Pinelli died, aged only 55, at the end of 1967. The owner of M.C.S., Rudolf Travnicek, had already passed away in 1965, aged only 44, while he was visiting the construction site of two 70mm new roadshow theatres. His wife, Hannelore Bollmann, continued to run the company, but M.C.S. produced no more feature films. |

|

Chapter 5: Under Foreign Flags |

|

Dieter Gaebler working on "Grand Prix", note Super Panavision 70 camera. Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Dieter Gaebler working on "Grand Prix", note Super Panavision 70 camera. Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionFrom the very beginning, the M.C.S. cameras had also been popular with producers who were filming in other wide film formats. Sometimes, a large-scale production had need of more cameras than the film rental house was capable of providing. Sometimes, M.C.S. equipment was preferred because of its minimal weight and compact construction. And sometimes there was simply no alternative. One could not, for example, make use, in a Todd-AO production, of the compact 65mm handheld or field camera introduced by Panavision in 1960/61, because Panavision always insisted on its name alone appearing in the credits. |

|

Dieter Gaebler working on "Grand Prix" with the MCS 70 field camera. Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Dieter Gaebler working on "Grand Prix" with the MCS 70 field camera. Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionThere can be no doubt that the M.C.S. images which have been seen by the greatest number of cinema-goers worldwide are those filmed in 1965 for "The Sound of Music" (1965) under the supervision of the M.C.S. technician Peter Rohe. Just like the other well-known work by director Robert Wise, "West Side Story" (1960), "The Sound of Music" opens entirely without music, but rather with quiet and deeply photogenic aerial shots of the Austrian mountain landscape above Salzburg. The camera plunges down onto a meadow, on which Julie Andrews is dancing and singing »The Sound of Music«. The film was shot in Todd-AO. But for the aerial shots taken from a light Alouette helicopter no camera would do but the small M.C.S Field Camera – which, satisfyingly, does indeed receive proper billing in the opening credits. No such formal recognition, however, was given of the camera’s use on the Todd-AO production "Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines" (1964) or on the racing-driver movie "Grand Prix" (1966), which brought the M.C.S. specialist Dieter Gäbler and two Field Cameras to the Formula 1 races in Monte Carlo (a location already visited in "Flying Clipper"). In the »featurette« documentary also filmed at the time, it is possible to recognize, in several shots, beside the Super Panavision cameras, also the M.C.S. Field Cameras. But Panavision Inc.’s restrictive trademark policy strictly forbade the producers to make any mention in the credits of any other manufacturer whose technology had been used. |

|

Bob Gaffney left filming "Fortress of Peace". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Bob Gaffney left filming "Fortress of Peace". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionAlso of technical and aesthetic interest are some short films which, quite aside from its use on feature films, were made with the camera for showings at national and international exhibitions. "Fortress of Peace" (1964) creates a very impressive visual record of an exhibition of the military skills of the Swiss Army and was even nominated for an Academy Award. And "Sky over Holland" (1966) and "Motion" (1967), too, are veritable showcase films that serve to demonstrate the full capabilities of the 65/70mm format, featuring a whole range of truly spectacular shots. On "Motion", in particular, the resources of the Field Camera were tested to their very limit. Cameraman Robert Gaffney was not content just to mount his shooting equipment on every conceivable type of land and air vehicle. He also filmed the breathtaking formation parachute jump of a group of skydivers – something at that time never yet attempted in 65mm format and with wide-angle lens. To achieve this, an aerodynamically crafted »drop capsule« was specially built, which, once the filming work was completed, could also land safely on the ground by means of its own parachute. |

|

Bob Gaffney filming "Fortress of Peace". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Bob Gaffney filming "Fortress of Peace". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionIt is a little-known fact that M.C.S. teams were also involved in the making of Stanley Kubrick’s outer-space epic "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1965-68). They contributed, to the final phases of the film’s famous »Stargate«, sequence certain aerial shots of sunrise in America’s Monument Valley which were then processed in post-production so as to alter and distort their natural colours. It was indeed Robert Gaffney, who was a personal friend of Kubrick’s, who had persuaded the director to use the 65/70mm process to realize his vision of the future. Kubrick was also planning to use 70mm on the film about Napoleon which he wanted to make directly after "2001: A Space Odyssey" – but this project failed to receive the necessary funding. |

|

Chapter 6: The Third Dimension, and the Finale |

|

70mm frame from "Love in 3D". Image Schauburg Kino 70mm frame from "Love in 3D". Image Schauburg KinoThe end of the 1960’s also saw the end of the great era of widescreen and large-format film production in Europe. The Zeitgeist was one inhospitable to the aesthetic of large-format film, since many young film-makers were tending to repudiate, as one of the ideological weapons in the arsenal of an old-fashioned and despised »Papa’s Kino«, precisely the »breathtaking« potentialities of the cinematic image. The order of the day was naturalism and what was taken to be cinematic »authenticity«. It was not only in the West but also in the socialist states of the East that the production of films in panoramic and widescreen formats dried up around this time. That is to say, the development was surely not one dictated by economic considerations alone. Technirama vanished as a production format in 1967. The number of CinemaScope films fell sharply. Only the »economy« format Techniscope-II succeeded in maintaining a hold for a few years longer. The few 70mm copies of new films presented in cinemas at this time were in almost every case »blow-ups«, that is to say, optical enlargements from the smaller 35mm format. |

|

Dieter Gaebler filming "Savage Pampas". Image Dieter Gaebler's Collection Dieter Gaebler filming "Savage Pampas". Image Dieter Gaebler's CollectionAfter the release of two last M.C.S. Superpanorama feature films, "Savage Pampas" (E/ARG/USA 1966) and "Doctor Coppelius" (E/USA 1968), the European wide film system gradually settled into dormancy and inactivity. It was, however, not long before Rudolf Engelbrecht – who had already some years earlier brought Jan Jacobsen together with the financial backer Travnicek – persuaded the same inventor to complete, using the existing M.C.S. cameras, an improved 3D cinema process that had been mentioned as early as 1962 as a next possible step for M.C.S. technology. Jacobsen was able, as it were with a flick of the wrist, to solve every one of the problems that had hitherto been troubling stereoscopic film-making, simply putting the two stereo images side by side with another on a single strip of 65/70mm film. The wide-aspect-ratio image required was achieved through anamorphic compression of the two stereo views, an operation in which Jacobsen was able to apply all the experience he had gained with anamorphic cylindric optics. A special projection lens called the »Stereo-Kinotar« on the 70mm projector unsqueezed both images, adding polarization to each view and overlapping both images on the silver screen, so that viewers equipped with polarized-glasses were able to experience a three-dimensional colour moving image of high quality. The process was superior to the double-strip 3D films of the 1950’s inasmuch as here there was no unsteadiness or colour difference between left/right images, and superior also to the single-film »over/under« 35mm stereo formats, in that the image still looked bright and clear despite the numerous light-absorbing filters. For the stereoscopic work, Filmtechnik Fromm in Munich simply modified the viewfinder systems of two of the three M.C.S. studio cameras. |

|

70mm frame from MCS 70 advert for "Stuyvesant" cigarettes. Image Schauburg Kino 70mm frame from MCS 70 advert for "Stuyvesant" cigarettes. Image Schauburg Kino"With Death on Your Back" (E/I/F 1967) was the first production to appear in cinemas under the trademark HIFI-STEREO 70 . There followed some Spanish horror films, such as "La Marca Del Hombre Lobo" (E 1967), processed at Fotofilm S.A. film laboratories in Madrid. Best-known, however, was surely the German 3D film "Love in 3D" (BRD 1972), which, in the most various formats and conversions, became a huge success worldwide. |

|

Ole Mads Sirks Vevle working on MCS 70 short film "Tanakh Bibelen Al-Quran". Image Ole Velve Ole Mads Sirks Vevle working on MCS 70 short film "Tanakh Bibelen Al-Quran". Image Ole VelveThe beginning of the 1970’s saw at least a provisional end to the era of large-format cinema, and the HiFi-Stereo-70 system served in the following years only for the production of such special venue productions as films designed for amusement parks and special fair installations. Two of the M.C.S. Field Cameras were sold to NASA, where they were used to document rocket launches, and another is still in use today in the Gulliver/Arane 65/70mm film lab, proving its worth again most recently in the shooting of the Norwegian short "Tanakh Bibelen Al-Quran" (2007). |

|

70mm frame from "Fanny's Wedding". Image Olivier Brunet 70mm frame from "Fanny's Wedding". Image Olivier BrunetIn retrospect it is clear why the M.C.S. format did not and could not yield any »mega-classics« which would have represented for European cinema what "Lawrence of Arabia", "Ben-Hur", "Around the World in 80 Days", "Spartacus" or "Ryan’s Daughter" represented for the specific widescreen processes that were used to make them. The M.C.S. technology, indeed, was fully developed and well proven in practice, as is undeniable when one looks at the many vintage prints still available today. Europe, however, lacked directors and producers who were able to give a content to the massive framework that the process put at their disposal. But the M.C.S. films are for us, today, also a kind of time machine that carries us back into a period of radical change, both in manners of production and in forms of reception, within that interconnected system which we nostalgically refer to as »cinema«. Beyond and aside from the filmed stories themselves, the genres, and the evaluations of the critics, there still remains a great deal to discover. Above all, we should honour and appreciate the craftsmanlike labours of all those whose creative work was, just shortly after its completion, so unfairly and so undiscriminatingly dismissed and condemned by the rising generation as a shallow and outmoded »Papa’s Kino«. |

|

The author would like to thank: |

|

GERHARD

FROMM, Munich; inventor, author of numerous technical publications and

filmtechnique historian. He was a tremendous source of information about Jan

W. Jacobsen. Assistant cameraman with the M.C.S. production "Uncle Toms

Cabin". Owner of company „Filmtechnik Fromm“ and member of the B.V.K. GERHARD

FROMM, Munich; inventor, author of numerous technical publications and

filmtechnique historian. He was a tremendous source of information about Jan

W. Jacobsen. Assistant cameraman with the M.C.S. production "Uncle Toms

Cabin". Owner of company „Filmtechnik Fromm“ and member of the B.V.K.imdb.com |

|

DIETER

GAEBLER, Gräfelfing; DoP, worked for „Modern Cinema Systems KG“ and was

involved in the shooting of a lot of M.C.S. movies. He did a few sequences with

the M.C.S. camera for "Grand Prix" and "2001: A Space Odyssey".

Without him we would not have been able to clear a lot of detailed questions

regarding M.C.S. DIETER

GAEBLER, Gräfelfing; DoP, worked for „Modern Cinema Systems KG“ and was

involved in the shooting of a lot of M.C.S. movies. He did a few sequences with

the M.C.S. camera for "Grand Prix" and "2001: A Space Odyssey".

Without him we would not have been able to clear a lot of detailed questions

regarding M.C.S. imdb.com |

|

HEINZ

HÖLSCHER, Munich; DoP since 1951 on more then 80 feature films. Worked with

M.C.S. cameras for "Flying Clipper", "Der Kongress amüsiert sich".

German award for his camera work on "Uncle Toms Cabin" in 1966.

Member of B.V.K. HEINZ

HÖLSCHER, Munich; DoP since 1951 on more then 80 feature films. Worked with

M.C.S. cameras for "Flying Clipper", "Der Kongress amüsiert sich".

German award for his camera work on "Uncle Toms Cabin" in 1966.

Member of B.V.K.Without the memories and detailed explanations of these men this brief history of M.C.S. would not be possible. Thanks to Dr. Ursula von Keitz, Bonn and to Albert H. Knapp, Frankfurt, for their help in preparing this article. imdb.com |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|