The Hollywood Legion Theater: How military veterans are fighting to preserve 70mm |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Bill Steele, Theater Director, American Legion Hollywood Post 43 | Date: 11.09.2020 |

American

Legion Post 43 facade. The building is an L.A. Historic-Cultural Monument

designed by Weston & Weston architects, 1929. Photo: Taiyo Watanabe American

Legion Post 43 facade. The building is an L.A. Historic-Cultural Monument

designed by Weston & Weston architects, 1929. Photo: Taiyo Watanabe Does one film show really matter? That thought ran through my mind at a major film festival in Hollywood last year as our theater darkened and curtains opened on one of the most revered films in movie history, in 70mm. That’s right. 70mm. As project manager of the American Legion Hollywood Post 43’s remodel of their historic theater, I was heavily invested in the answer. This was our first-ever public screening of a 70mm film, and I was first-date nervous. "The Sound of Music" might be a modern-day technical disaster. Though we had opened the festival the night before with a flawless screening of a 35mm print of Sergeant York, this time was different. 70mm is a tricky, unforgiving format, and the tiniest error or misjudgment can spell disaster. Adding to my anxiety, among the audience members were studio archivists, festival executives, and technical bigwigs. Any error in presentation would surely be noticed and harm our nascent reputation. Knowing all too well the fragility of the film medium—I’ve seen beautiful archival prints get damaged or destroyed at highly reputable theaters more than once—I prepared for the worst. • Go to Gallery The Hollywood Legion Theater Up in the projection booth, our chief projectionist, Taylor Umphenour, and our engineer, Roger Addams, nervously eyed our 55-year-old Norelco AAII machines for any signs of trouble. Three years of exhaustive work, deal-making, false leads, dead-ends, soul-searching, broken friendships, and personal sacrifice had all come down to what felt like a decisive moment. Would this show end up defining us? As the film began, I stood in the back of the 482-seat theater like a superstitious actor before a performance, afraid if I sat down I might jinx not only our shining moment in 70mm but also the improbable story of how a group of military veterans dusted off a 90-year old Hollywood relic and elevated it into a world-class facility. But before I get into that story, it’s worth revisiting a bit of history. The American Legion Post 43 dates back to the end of World War I, when a group of returning army veterans who worked at the Famous Players-Lasky Studios (which later became Paramount Pictures) chartered what was then referred to as the “Motion Picture Post” in 1919. It is one of the oldest in the state of California. Over the years, members have included Hollywood luminaries such as Walter Long, Adolf Menjou, Clark Gable, Mickey Rooney, Gene Autry, Charlton Heston, Ronald Reagan, Stan Lee and many others who have served in the military. |

More in 70mm reading: Gallery The Hollywood Legion Theater Ronald Rosbeek in Conversation Ronald Arnold Rosbeek passed away 70mm Cinemas in North America DP70 / Universal 70-35 / Norelco AAII - The Todd-AO Projector |

Legion

Theater. The upper areas of the side walls are covered in fabric panels with fiberglass insulation in the cavity behind. The red panels are wedge-shaped

and contribute to the visual character of the space, picking up on the Art

Deco theme in the building, but also offer a broader band of lower frequency

absorption due to their varying depths - Peter Grueneisen, architect. Photo:

Taiyo Watanabe Legion

Theater. The upper areas of the side walls are covered in fabric panels with fiberglass insulation in the cavity behind. The red panels are wedge-shaped

and contribute to the visual character of the space, picking up on the Art

Deco theme in the building, but also offer a broader band of lower frequency

absorption due to their varying depths - Peter Grueneisen, architect. Photo:

Taiyo WatanabeThe original purpose of the American Legion was to help post-discharge veterans “preserve the memories and incidents” of their participation in the Great War. Early on, the founders of Post 43 decided to build a memorial in honor of the war’s dead. Needing an income source, the Post bought land on El Centro Boulevard and built the Hollywood Legion Boxing Stadium in 1921. It soon became wildly successful, a place where celebrities hung out. Charlie Chaplin had a ringside seat. Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney were regulars. Many attended “Friday night fights” to see movie stars as much as to watch boxing. The enormous gate receipts of the boxing events enabled the post to build a massive, $300,000 memorial clubhouse on Highland Ave. in 1929. Constructed of board-form concrete in the Egyptian-Revival style, the 30,000 sq. ft. edifice featured an exercise room, trophy rooms, lounge areas, a speakeasy bar, and an expansive “meeting hall” for member functions that doubled as a movie theater. An ample projection room was built with steel-reinforced walls eight inches thick. Though the building had undergone a few alterations over the years, mostly to the downstairs bar area, when I joined the club in 2015 it was essentially unchanged. At the time, I was residing in Lawrence, Kansas and occasionally flying to Los Angeles to perform reserve duty with the U.S. Navy’s Hollywood liaison office. Off-duty, I frequented the city’s repertory cinemas and old movie palaces, seeking ideas for an arts house cinema I hoped to build in Kansas. (It was an effort that proved futile.) I was at a low point when one evening in March 2015 a fellow navy reservist, Fernando Rivero, invited me to have a cigar and drinks at a favorite hangout of his in Beverly Hills. After downing a couple of Scotches, I shared my Cinema Paradiso dreams. Fernando suddenly perked up and took a puff on his cigar. He said he was spearheading a project to remodel an old theater at the Hollywood American Legion, where he was a member and chaired their cinema committee. Before the night was over, he asked if I would be interested in moving to L.A. and helping him manage the project. |

|

Art

Deco bar. The wall in the far background is lined with original WWI posters.

Photo: Jon Endow Art

Deco bar. The wall in the far background is lined with original WWI posters.

Photo: Jon EndowThough flattered by the offer, I politely declined. The idea of remodeling a movie theater at an American Legion didn’t sound very appealing. I envisioned a dank auditorium with a pulldown screen and speakers propped up on poles. And my image of Legionnaires was firmly stuck in the past: old men in funny hats waving tiny American flags on sticks at Veterans Day parades. I wasn’t interested. Two months passed and I was back in Los Angeles for more Navy duty. This time Fernando invited me to come check out the Legion building. Somewhat reluctantly, I accepted and drove over to the Highland Ave. location, just south of the Hollywood Bowl. I met Fernando and the club’s historian, Mike Hjelmstad, in the downstairs bar, a time capsule from the 1940s. I thought I knew what to expect when we headed into the old theater but I was completely taken by surprise when the heavy church-like oak doors were flung open. It was one of the most dramatic entries I had ever experienced in architecture. Arched buttresses more than 40 feet high descended from the ceiling to enclose a space that seemed cavernous, yet intimate. Not lavishly ornate like most 1920s-era grand theaters, this was an unusual blend of stripped-down classical with a hint of art deco. A dark red curtain hung across the 45-foot stage lent an air of elegance. I sensed immediately that the room had the potential to become a movie palace unique in cinema. I also knew this: that if my insanely unlikely dream of one day exhibiting 70mm films was ever going to be realized, this was my chance. Four months later, in September 2015, I quit my dead-end job in Kansas, kissed my wife, and drove out west. I had just turned 51. A sound option While eager to get to work when I arrived in Los Angeles, the Post 43 organization was in no hurry to employ me. A byzantine approval process held up my hiring for months, during which time I took a job doing data entry at an entertainment payroll company to make ends meet. In the interim I became a member of the post and joined the cinema committee, where I became acquainted with an impressive group of member volunteers that Fernando had recruited for the project, including an Iraq War veteran with an MBA, a retired construction manager, and a retired project manager. When I was finally hired in December, we had our work cut out for us. Our initial approved budget was $400,000 to remodel a 90-year-old auditorium into a state-of-the-art high-end movie theater. It was like asking NASA to build a spaceship with a set of woodworking tools. |

|

L-R:

Peter Grueneisen, Fernando Rivero, Bill Steele and John Bertram L-R:

Peter Grueneisen, Fernando Rivero, Bill Steele and John BertramIt soon became clear that we needed to invest more in the project if we had any hope of having a theater where we could rub shoulders with the likes of Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan. Among the myriad problems that needed to be overcome, one loomed largest: the acoustics. The room was not an acoustically optimal shape, having ratios that were bad for standing waves and resonances, and concrete surfaces that efficiently reflected sound waves. We conducted an RT-60 test, revealing a reverb decay time of 2.4 seconds at 1kHz, an excessive amount. In short, it was terrible for cinema and would likely require aggressive and costly treatments to obtain acceptable results. The odds of success seemed unlikely. Feeling deflated, I nearly lost hope. Shortly thereafter, while reading a book about acoustics in historic buildings, I came upon a passage that stopped me cold: back in the 1950s and 60s, the American Legion hall had become a highly sought-after recording location for classical music. The composer Salvador “Tutti” Camarata, who wrote many of the classic Walt Disney melodies, had recorded interpretations of Cinderalla and Bambi there, and Stravinsky had recorded many of his greatest classical works there for Columbia Records. They all raved about the sound of the hall. How could this be? My attitude about the acoustics did a 180. Instead of aggressively deadening the space—which would surely destroy its architectural character—I thought that if we could somehow preserve the hall’s exceptional acoustic properties we might create something truly magical in cinema sound. We just needed to find the right architect to do it. Based on a referral from John Bertram, a modernist architect known for his work restoring Richard Neutra houses, we hired Peter Grueneisen in May 2016. A Swiss-born architect, Peter specializes in designing sound studios for recording artists, and has done a lot of projects for Hans Zimmer. Though Peter had written a book on architecture and music and knows more about acoustics than most architects, he recommended that we hire an acoustical engineering firm, Arup, to model the hall for his proposed acoustic treatments. The goal was to bring down the RT- 60 values across a broad bandwidth, with a reverb time of about one second. Early in the design development phase, Peter, Fernando, myself and a few others on our cinema committee were invited to Arup’s Soundlab in Santa Monica for an acoustical simulation. Technicians played an audio track from a scene in "Back to the Future" as they virtually applied various treatments to our theater’s acoustical model. Although it was just an aural impression, it became obvious that if we didn’t acoustically dampen the ceiling we would be unable to follow the soundtrack. The voice intelligibility difference between treated and untreated was night and day. Once again, my heart sank. |

|

Legion

Theater. Photo: Taiyo Watanabe Legion

Theater. Photo: Taiyo WatanabeOur revised budget for the remodel—which took months to get approved—was $1.75 million, and that didn’t include the cost to treat the ceiling. When we got the estimate for that, our eyes nearly popped out of our heads. More surprises were to follow. It turned out that our initial cost estimates were overly optimistic. Expenditures were already starting to go over budget, and we hadn’t even started construction. Compounding my nervousness was the fact that we had only budgeted for a DCI-compliant digital projection system with Dolby 7.1 sound. Our business plan was based on studio rentals and other Hollywood screenings, not running film, let alone 70mm film. Meanwhile, many AV contractors and other experts I was dealing with warned me against doing changeover 35/70mm. They told tales of lost time, lost money, and wrecked reputations with associates. They wanted nothing to do with 35/70—not planning it, installing it, supporting it, anything. Despite this discouragement I was undaunted. After all, one of the main reasons I got involved in the Legion project was for the thrill of 70mm. And frankly, the notion that such a magnificent historic theater in the heart of Hollywood wouldn’t have film capability was simply inconceivable to me. I felt it was my patriotic duty to install film projectors. Thankfully, Fernando was willing to support my Trojan Horse scheme. A talented filmmaker in his own right who worked as a trailer producer for the FX TV network, he fell in love with the movies after seeing "Lawrence of Arabia" in 70mm as a teenager. By now Fernando was serving on the post’s executive committee and was next in line to become commander. With his salesmanship skills, our “fearless leader” was able to mobilize considerable internal support for the theater remodel, despite naysaying by skeptical Legion members. This helped buffer my growing alarm over costs and the feasibility of pulling off 70mm. Search and destroy Shortly before we were to start construction in the summer of 2017, Alarm bells went off when I got a phone call from my film consultant, Jess Daily. A retired chief projectionist at the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Jess and I were close friends and had spent many nights by the campfire devising the ultimate projectionist-friendly booth. He had called to provide comments on Peter’s finalized architectural plans I had sent for the baffle wall speaker placement. He noticed that the plans called for three screen channels, not five. In my naivete and desire to keep costs down, I had assumed with our smaller screen size—38 feet—that three channels would be good enough for 70mm.

Of course, he was right. What was I thinking? I

began to question my commitment to the format. The costs steadily mounted as the

invoices kept coming in: custom-machined shafts, rollers, spacers, adapters,

custom-made projector bases. At one point our finance officer, Terrence Pallend,

a former marine and Iraq veteran, began to question all the money being spent up

in the booth. “What is all this stuff for 70mm?” he pointedly asked. Seeing an

opportunity, I asked him if he’d ever watched a film in 70mm before. No, he

said, what’s the big deal? |

|

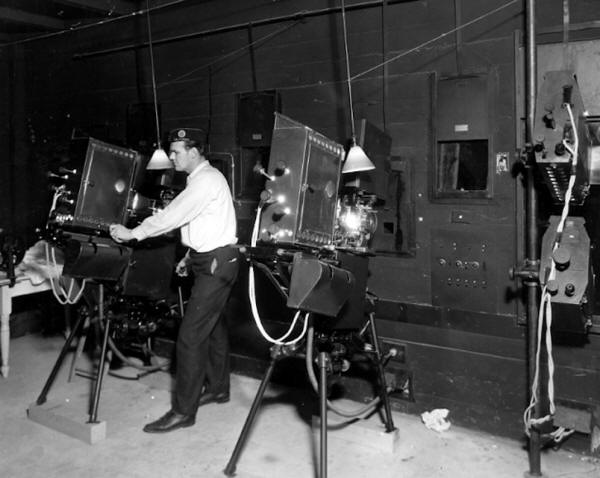

Legion

booth circa the 1930s Legion

booth circa the 1930sAs it just so happened, Dunkirk was out in theaters and Jess was projecting it on the side at an AMC 16 in Burbank. I invited Terrence to come see what all the fuss was about. He agreed and off we went the next day. We got a tour of Boston Light & Sound’s innovative platterized projection system and then watched the movie in the theater. Terrence came away impressed not only with the beauty of 70mm but also the technical aspects of film projection.

We were far from out of the woods, however. Jess and I were still on a search

and destroy mission to find a decent pair of Norelco AAII machines and all the

necessary parts. This was getting harder and harder by the day. A small pool of

eccentric and unreliable equipment hoarders had cornered the market on nearly

everything. One infamous projectionist had collected nearly

20 AAIIs in Illinois, with lots of spare parts, but became impossible to negotiate with.

Then there was Charles Massa, who possessed a motherlode of 70mm film equipment

in Sun Valley. A sweet, elfin fellow with a crinkly smile, Charles sizes up his

customers like a shady art dealer, and prices accordingly. Our search continued. |

|

Projection

Booth 2020. Photo: Taiyo Watanabe Projection

Booth 2020. Photo: Taiyo WatanabeIn addition to the theater remodel, which was almost done, we were also updating other spaces in the building. This effort was seriously lagging. I struggled to keep up with the demands of project managing the theater and helping supervise the house renovations. Up in the projection room, the situation had devolved into a quagmire. There were problems with the HVAC system, lighting, electrical and plumbing. My relationship with Jess was starting to fray over differences in expectations that manifested in battles over minor details like electrical outlets and track lights. Finally, early one morning Jess had had enough and came to visit me in my office.

I was stunned. The person I relied on most to

develop an archive-quality film projection operation was gone. Making matters

worse, I was scheduled to interview one of Jess’s recommended projectionist

candidates—our first crucial hire—twenty minutes after he quit. I wondered if

the candidate would even show up. I thought, this is it. Game over. |

|

Taylor

Umphenour and Leonard Maltin. Photo: Carol Ann Van Natten Taylor

Umphenour and Leonard Maltin. Photo: Carol Ann Van NattenIronically, running out of money was a blessing in disguise. We now had room to focus on getting the film system operational, which had taken a back burner to running digital shows as our theater gradually opened. We also had new target to shoot for: The Turner Classic Film Festival, held each April in Hollywood. Early on in the project, organizers of the festival got wind of our remodeling plans and made a number of site visits in hopes of adding us as a new venue to their roster, which includes the Chinese and Egyptian theaters. When they learned that we could potentially run film they became keenly interested. In late December, I got an email from the festival’s managing director, who asked if we could have 70mm ready in time for the festival. Going completely out on a limb, I replied yes. Without fully realizing it, I had just cinched a noose around my neck. We were nowhere near ready for 70mm or any film gauge for that matter. The lamphouses still had no 3-phase power. We had the wrong reflectors, the wrong lenses, and we needed a new intermittent sprocket, gate pad roller assembly, DTS player and aperture plates. The list went on and on. Well, I figured, we’ve got about two months to work it all out. We’ll get there. Wrong. While enjoying a relaxing holiday break back in Kansas, sipping a glass of wine with my wife, I received an email reminder about an event scheduled in the theater for the middle of January, two weeks away. It was a demo of our Alcons Audio sound system and 70mm capabilities to an audience of International Cinema Technology Association professionals! I had completely forgotten about my casual offer to run 70mm to the event planners made months earlier. In a panic, I cut my vacation short and flew back to L.A. The next two weeks were a blur. While Roger and Taylor labored to get light on the screen, I furiously hunted down the necessary equipment. Luckily, we only needed to get one projector working to run a reel of film for the demo. Unfortunately, we couldn’t find an odd reel of 70mm to save our lives. The situation became critical. At the last minute, we were able to borrow a spare test reel of Kenneth Branagh’s "Murder on the Orient Express" thanks to our friends at Kodak and Fotokem. We picked up the reel the day of the event and ran it just in time for the roughly 100 ICTA audience members. Though we had aperture plates that looked like they had been filed by a lumberjack, the overall picture was bright, beautiful, and seductive—just as 70mm should be. Together with the powerful and precise Alcons ribbon-based system, the result was very impressive. We all went down to the bar after the event and felt we had pulled off a miracle. Our next challenge came about a month later when TCM’s technical director, Chapin Cutler, arrived to assess our readiness for film projection. By this time we had made significant improvements to our 70mm kit. Notable was the innovative work done by our AV integrator, Levi Joos, to replace Dolby’s ancient CP200 cinema processor, the 70mm mainstay for years. Using a new Q-SYS Core 510 processor, Levi figured we could apply the same filters and crossovers for each of the individual 70mm formats as the CP200 provided if we followed Dolby’s original specs. With help from Dolby’s Gary Meissner and Dustin Hudson, Levi created a signal path that was all-digital throughout. This greatly improved the sound quality. We ran some 70mm changeover reels for Chapin and awaited his verdict.

The Christening |

|

A unique element of the Legion Theater is the use of the

customized wood wall panels at the ear level of the audience. The idea was

to use images from war movies and to pixelate them to abstraction, then use

the resulting patterns to cut holes into the wood. Complemented with

acoustically absorbent materials behind the panels, the pattern provides

both absorption and reflections, while infusing the space with the imagery

related to the Legion’s military veteran membership - Peter Grueneisen,

architect. Photo: Taiyo Watanabe A unique element of the Legion Theater is the use of the

customized wood wall panels at the ear level of the audience. The idea was

to use images from war movies and to pixelate them to abstraction, then use

the resulting patterns to cut holes into the wood. Complemented with

acoustically absorbent materials behind the panels, the pattern provides

both absorption and reflections, while infusing the space with the imagery

related to the Legion’s military veteran membership - Peter Grueneisen,

architect. Photo: Taiyo Watanabe

In the days leading up to our 70mm debut, that

limit would be tested. With multiple formats to project, our problems were

magnified--literally. Our attempts to cut aperture plates for 1.33, 1.37, 1.85

and 2.20 were a maddening exercise in frustration, and at the same time we were

having issues with "The Sound of Music" print. The 70mm reels we received from the

Fox archive looked dim on our 1.0 gain screen, leading us to think there was

something wrong with our equipment or setup. Roger, Taylor, Boston Light &

Sound’s Diana Caldwell, and Fox archivists spent days trying to resolve the

problem. Alas, a mix-up had occurred, and the wrong print was sent. We got the

replacement—a pristine show print straight from the vault--just in time for the

show. |

|

Roger

Addams at work on the AAII's optical sound heads. Photo: Bill Steele Roger

Addams at work on the AAII's optical sound heads. Photo: Bill SteeleWhen the show ended, I hustled up to the booth to give Taylor a hug. Largely thanks to his tremendous energy level, stamina, and persistence, we had achieved what only months earlier had seemed impossible, and I couldn’t have been prouder of him. “You nailed it!” I exclaimed. “It was the perfect show!” But as I later found out, little did I know just how close we had come to disaster. In his relentless pursuit of perfection, after reel one was finished, Taylor had pulled the hot aperture plate from the projector and taped one side of it to conceal a jagged mountain range absorbed by the masking but still visible in bright scenes. A fraction of a millimeter off would have resulted in a horrible loss of picture. A huge risk! But it landed perfectly. Taylor had memorized the shape of the mountain range and knew that if he covered it up and kept it flush it would work. The change was so subtle as to be imperceptible. Indeed, after the festival wrapped, Fernando received some technical feedback from head Fox archivist Schawn Belston, who was not able to attend the screening, relayed from his Fox colleagues who were able to attend. They described it to him as simply, “the best technical presentation of "The Sound of Music" they’d ever seen.” The Legion Theater had received the blessing of the high priests of cinema. I was overjoyed. Taylor was over the moon. Fernando was ecstatic. His vision of reviving Post 43’s moribund theater, and making veterans relevant again in Hollywood, had come to fruition. We had done it, and proven that one film show can, especially if it’s in 70mm, matter more than anything. Postscript Following last year’s TCM Film Festival, the Hollywood Legion Theater went on to host a number of notable screenings and events, including a sold-out presentation of Peter Jackson’s WWI documentary "They Shall Not Grow Old" in partnership with the UCLA Film & Television Archive; a private cast-and-crew screening of Quentin Tarantino’s "Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood" in 35mm; Fox Searchlight’s premiere of "JoJo Rabbit"; a Veterans Day screening of “The Right Stuff” with director Phil Kaufman on stage in partnership with the American Cinematheque; a special screening of "1917" hosted by the Veterans and Military Affairs office at Universal Pictures; and a sold-out screening of Charlie Chaplin’s "The Gold Rush" in 35mm with live musical accompaniment, done in partnership with Retroformat Silent Films. On March 10, 2020, just before the COVID-19 shutdown of the theater, we showed "Act of Violence" and "Somewhere in the Night", both in 35mm, as part of the Noir City: Hollywood film festival. In October, 2020, we converted our parking lot into a drive-in cinema, the first-ever to open in the heart of Hollywood. The Legion Drive-In features a 38 ft. screen--the same size as our indoor theater--and features a pair of Simplex X-L dual format 35/70 film projectors, making it one of only two drive-ins in the United States that still projects movies on celluloid. In May, 2021, we reopened the theater with special screenings of "Tenet" (2020) and "Dunkirk" (2017) in 70mm, both of which looked and sounded incredible. In the booth, we also have made incremental improvements to the film system. These include installing new multi-phase motors with variable speed controllers, a top-to-bottom realignment of both projectors, and most recently, the addition of Rosbeek-Techniek gate runners for 70mm. These have further improved picture stability. Sound-wise, Roger performed multiple surgeries on the sound heads and experimented with different wires to reduce noise in our optical signal path. This has significantly improved the optical sound quality. Nevertheless, work still remains to be done with our 4- and 6-track magnetic sound. Operationally, Taylor remains our chief projectionist, with Scott Duvall and Tim Kennelly rounding out the projection team. Roger continues to provide his superb engineering support. Last year I was promoted to theater director, and my wife joined me in Los Angeles this year while on sabbatical. Last year we also had the great fortune to have noted author and film historian Alan K. Rode join our coterie. Alan is the director-treasurer of the Film Noir Foundation who has programmed and hosted local and national events for decades. A retired navy veteran, he joined Hollywood Post 43 last year and currently serves as our cinema committee chair and resident film nut. The future, as they say, looks bright. For more information about the Legion Theater visit their website. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |