Restoration of "Vertigo", 1996 |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Universal Pictures press, 1996. Thanks to Universal Germany and Bob Harris | Date: 29.08.2015 |

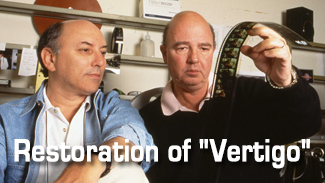

Robert

Harris (right) and James Katz (left) with 70mm cans for "Vertigo". Image

source: Robert Harris.

Picture credit: Laura Luongo Robert

Harris (right) and James Katz (left) with 70mm cans for "Vertigo". Image

source: Robert Harris.

Picture credit: Laura LuongoIf the greatest movies, like the greatest of loves, are meant to linger in the imagination forever, Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo" is an astonishing act of seduction. The director's darkest, most dream-like tale of suspense, it draws the audience in with the air of a mystery then plunges into a dizzying exploration of romantic obsession. Today, this same explosive theme, that of a man possessed and a woman hiding secret identities, has continued to excite audiences in some of cinema's biggest box-office suspense thrillers. But from its head-spinning imagery to its shocking psychological revelations, from its breathtaking cinematography to its dramatic Bernard Herrmann score, from its unwavering sense of mystery to its unanswered questions, Vertigo remains that irresistible first love. Once seen, it cannot be forgotten; and the more times one sees it, the more fascinating it becomes. Yet the full seductive powers of "Vertigo" have been marred up until now by deteriorating negatives and prints - prints that cut the visual allure that Hitchcock's most revealing film brought to audiences in its initial release. Now at last, following one of the most massive restoration projects ever undertaken, "Vertigo" will have a chance to win over new audiences and resurrect the passion of long-time fans in a stunning new 70 mm version featuring DTS digital stereo. Under the sponsorship of Universal Studios, Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz, the same team behind the restoration of such large-format films as "Lawrence of Arabia", "Spartacus" and "My Fair Lady", have spent the past two years painstakingly rebuilding, layer by layer, what is essentially a brand new 65 mm restoration negative. Dan Slusser, Senior Vice President/General Manager, Universal Studios recalls:

Casey Silver, Chairman of Universal Pictures, comments:

|

More in 70mm reading: in70mm.com's page about VistaVision “Vertigo”: The North American 70mm Engagements "Vertigo" Cast and credits "Vertigo" update in 70mm DTS Restoration of "Lawrence of Arabia" Restoration of "Spartacus" Restoration of "My Fair Lady" Robert A. Harris: Film Restoration on the eve of the Millennium A View from the Trenches |

"Vertigo"

1-sheet movie poster and lobby cards on display at the Schauburg VistaVision

film festival. "Vertigo"

1-sheet movie poster and lobby cards on display at the Schauburg VistaVision

film festival.Adds Jim Katz,

So it was with great sadness that film restorers James C. Katz and Robert Harris discovered that the perfection Hitchcock demanded had deteriorated into shrunken and vinegared sound elements and faded negatives that could not possibly do his dark romantic fable justice. For Harris and Katz the loss was unthinkable.

Although there is a feeling that once something is filmed it remains forever, it is sadly not the case. Images are fragile, their colors and tones easily fade away, and acetate safety film grows brittle and old. In fact almost 50% of all films ever made have been lost to the ravages of time.

For decades, Hitchcock's work was privately stored outside of the studios.

Unfortunately, hundreds upon hundreds of boxes filled with original

Hitchcock film material were junked just to save storage expenses. Even

worse, the material was stored in a vault that was not state-of -the-art and

unable to protect the negatives and black and white separations from the

ravages of climate and time. The loss was imminent. |

|

Robert

Harris (left) and James Katz (right) with 70mm frames of "Vertigo". Image

source: Robert Harris.

Picture credit: Laura Luongo Robert

Harris (left) and James Katz (right) with 70mm frames of "Vertigo". Image

source: Robert Harris.

Picture credit: Laura LuongoMartin Scorsese, a long-time supporter of their work, comments:

When Harris and Katz cracked the remaining film cans containing "Vertigo",

they had a good idea what they would find. "We knew exactly what to expect,

given the way the negative was stored and the peculiarities of the 1950's

film emulsions. We found fading and shrinkage, as well as torn negative

replaced with dupe, basically a film that looked and sounded nothing like

what Hitchcock had created," says Katz. He adds: "We're not magicians of

course and we can never restore the negative to mint condition. But we can

say that "Vertigo" will now be seen as Hitchcock could only have dreamed it

would look and sound."

To undertake this task, Harris and Katz were provided with over $1 million

from Universal, Hitchcock's final studio home since the early 60's, which

now owns the rights to 14 of the filmmaker's features, including "Vertigo".

Although the film was originally released in 1958 by Paramount, the rights

eventually reverted back to the director, moving with him to Universal,

along with other Hitchcock features from the late '40's to early '60's,

including "Rear Window", the 1956 remake of "The Man Who Knew Too Much" and

"Psycho". |

|

"Vertigo"

with DTS time code for the 70mm soundtrack play back. "Vertigo"

with DTS time code for the 70mm soundtrack play back.With the studio fully behind the project, Harris and Katz retired to the laboratory to do a transformation of their own. They divided the problems into two main areas: picture and sound. As Katz says: "Both were lousy." On the picture side, the restorers had to contend with the difficulty that "Vertigo" was originally shot in VistaVision, created by Paramount in the early 50's as a non-anamorphic, wide-screen alternative to Twentieth Century Fox's CinemaScope. But VistaVision is no longer utilized and the team had to undertake a restoration which would ultimately turn a 1:85 VistaVision negative into a 70mm print. Furthermore, Hitchcock's trademark use of rear-screen projection added another layer of complexity onto the restoration. Explains Harris: "With rear screen projection, you're already working with thinner, more faded negative and more problems present themselves." Other visual problems included unacceptable fading of Hitchcock's carefully chosen pastiche of colors. Never before had Hitchcock been so obsessed with color in a film -- from the color of Madeleine/Judy's hair to the themes of red and green -- stop and go -- running throughout. The wrong colors could seriously detract from Hitchcock's original intent. For example, during the inquest scene in which Scottie is questioned about Madeleine's apparent suicide, five men sit on the bench wearing the same blue suits --only by now their suits ranged from "marine to clown blue," says Harris. To get the color right, Harris and Katz had to go back in time, way back, even getting chips of paint from a circa 1957 green Jaguar to make sure the shade was correct! They also borrowed from Paramount Pictures many of the original wardrobe pieces designed by Edith Head to capture her vivid color designs. Explains Harris: "It was a very difficult process. Especially because the film was originally printed in the Technicolor process which hypes the color anyway. We had to do a lot of research with people who worked on the film and use any source material at hand to get close to the original." One interesting discovery was made: "No one realized for years how much yellow Midge wears. Now we see that was a part of setting her character," says Katz. In addition to fading, shrinkage was a serious problem in key scenes. Shrinkage refers to the shrinking of layers in the black & white separations, which can cause multi-colored rims to appear around the images. The only way to "fix" shrinkage is to mechanically, painstakingly, fit the separations back together layer by layer, as closely as possible. Just as the images had been fading and rotting in vaults, the sound elements of "Vertigo" were in similarly poor shape, with sound effects and foley tracks completely lost. Fortunately, Harris and Katz made one major find: the original orchestral recording sessions under conductor Muir Mathieson, which had been recorded in Germany due to an American musicians' strike. These elements had just barely survived a 1967 junking order (not from Paramount) and sat undisturbed, but rotting, in Paramount's vaults. |

|

Robert

Harris in the footsteps of "Vertigo". Mission Dolores Church and

Cemetery, location of Carlotta Valdes's grave. Image source: Robert Harris Robert

Harris in the footsteps of "Vertigo". Mission Dolores Church and

Cemetery, location of Carlotta Valdes's grave. Image source: Robert HarrisThe restorers took this remarkable recording and digitized it so that it would sing over today's speaker technology. Now, "Vertigo" becomes the first ever 70mm DTS release. Even those most familiar with the soundtrack were taken by surprise. "When we played it for some of Bernard Herrmann's people, they actually heard instruments and notes they'd never known were there," says Harris. "That's a wonderful feeling." But the foley tracks had to be completely redone from scratch -- although not without some direction from Hitchcock. Harris and Katz also came across Hitchcock's extensive and detailed notes on sound, which they used to copy the many eerie, lonely and ghostly sounds that make "Vertigo" so chilling. "Of course, we knew that Bernard Herrmann was notorious for hating sound effects over his score, so we wanted to be as careful as Hitchcock had been, using his pages and pages of notes on how to integrate the sounds from beginning to end," says Katz. Of all the pressures Katz and Harris faced, the greatest one may have been the shadow of Hitchcock looming over their work. "Hitchcock's standards of perfection are legendary and nowhere more so than on "Vertigo", admits Katz. "We were under extraordinary scrutiny from people who knew and loved Hitchcock. But even more importantly, we wanted to restore his film in a way that we were certain would make him proud." Katz is careful to differentiate a true restoration such as "Vertigo" from the numerous "restored prints" and "video restorations" -- many of which are merely reprinted -- that seem to be proliferating. "True restoration brings the negative close to its original quality in a form that will last for generations to come," he says. Adds Harris: "I feel confident that if Hitchcock were here today wanting to show this film to new audiences, he would take advantage of the technologies we used." One thing Hitchcock may not have counted on was the uncovering of an alternate ending to "Vertigo", which the director shot under pressure from foreign distributors who insisted on a more conventional final scene. This brief final scene ties up many of the loose ends that have given "Vertigo" its incredible power. Although the scene adds little to the film, it does incontrovertibly reveal how much more powerful the director's instincts were than any commercial suppositions. Thanks to this unprecedented restoration, these instincts will once again be on vivid display. For many filmgoers, it will be a welcome transformation of an old love. For those seeing "Vertigo" for the first time, it could be the start of an obsession. |

|

About the Restoration Team

|

|

Robert

Harris (left) and James Katz (right) visiting the portrait of Carlotta

Valdes - based on a portrait of Vera Miles. Image source: Robert Harris Robert

Harris (left) and James Katz (right) visiting the portrait of Carlotta

Valdes - based on a portrait of Vera Miles. Image source: Robert HarrisROBERT A. HARRIS mixes art with archaeology, bringing forth from the vaults some of the 20th Century's pinnacle achievements in cinema and magically reconstructing and restoring them for this and future generations to enjoy. A producer whose credits include the critically acclaimed "The Grifters" (with Martin Scorsese), Harris aided Kevin Brownlow in reviving Abel Gance's silent masterwork "Napoleon" and was instrumental in its presentation in a joint effort with Francis Coppola's Zoetrope Studios. Thinking it would be "fun" to restore the complete version of David Lean's "Lawrence of Arabia", Harris embarked on what turned out to be a two-year odyssey -- involving months of intensive research; more months of detective work as he literally scoured the world gathering over four tons of surviving picture and sound elements; and a touch of modern archaeology as he attempted to reconstruct an entirely new negative with neither a written continuity nor a surviving print of the original premiere version to work with. The end result, however, was proclaimed one of the great triumphs of film reconstruction and went on to win over new audiences in theatrical release. Harris, along with partner Jim Katz, followed "Lawrence of Arabia" with another triumphant restoration of Stanley Kubrick's "Spartacus" for Universal Pictures, establishing them as the world's foremost experts in complex, large-format reconstruction. Most recently, Harris and Katz restored the classic American musical "My Fair Lady", using the latest in digital technology to bring a badly damaged negative back to stunning, new life. Harris is currently planning an original feature and preparing for another major restoration, both with Jim Katz. JAMES C. KATZ has built a career equally focused on preserving the old and creating the new in cinema. On the new side, he has produced such features as Paul Bartel's "Scenes From the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills" and "Lust in the Dust" and was co-producer of "Nobody's Fool", written by Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Beth Henley. As President of the Universal Pictures Classics Division in the early 1980's, Katz was responsible for the reissue of five Hitchcock films-- "Rear Window", "Vertigo", "Rope", "The Trouble With Harry" and "The Man Who Knew Too Much" --the reissue of the Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night", the Preston Sturges package and Abel Gance's "Napoleon", during which he cemented his partnership with Bob Harris. At the same time, under Katz' aegis, Universal Pictures Classics became the first classics division to be involved in film production with John Huston's "Under the Volcano". Katz was also involved in bringing such films as Jerszy Skolimowski's "Moonlighting", Merchant Ivory's "Heat and Dust", Nagia Oshima's "Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence" and Franco Zeffirelli's "La Traviata" to U.S. audiences. During this time Katz' concern with the state of film art converged with Bob Harris' skills in film reconstruction and restoration. Together the team brought film audiences a celebrated reconstruction of Stanley Kubrick's "Spartacus" and a wondrous new transformation for the Oscar-winning musical "My Fair Lady". Katz began his career in the 1960's in the United Artists publicity department, eventually becoming Vice President of Worldwide Publicity. He was involved in campaigns for such films as the Clint Eastwood Spaghetti Westerns, the James Bond movies, "In the Heat of the Night" and two Beatles movies, "A Hard Day's Night" and "Help!" He subsequently lived in Europe for 10 years, where he produced and directed short films and co-produced the National Theatre's production Chekhov's Three Sisters starring and directed by Laurence Olivier. |

|

Filming of "Vertigo" |

|

VistaVision

advert from Paramount Pictures. "Vertigo" was filmed in large format

VistaVision. VistaVision

advert from Paramount Pictures. "Vertigo" was filmed in large format

VistaVision."Vertigo" was filmed in 1957 on location in Northern California and on the stages at Paramount Studios. Those who were on the set recall that Hitchcock's famous attention to detail was heightened more than ever on this film. The color, the visuals, the performances - everything had to be absolutely perfect. Kim Novak recalls the director employing a metronome "to try to get the right rhythms for certain scenes, like going up the spiral staircase, to get that staccato feel. And it had to be exactly so." Screenwriter Samuel Taylor later said, "Hitchcock knew exactly what he wanted to do with this film, exactly what he wanted to say, and how it should be seen and told... and anyone who saw him during the making of the film could see, as I did, that he felt it very deeply indeed." The reasons why "Vertigo" touched Hitchcock so deeply have been debated in endless books and articles, but there is no doubt that the themes of the film - the fallibility of romantic love, the power of transforming reality into make believe, the temptation of molding women into unattainable beauties, the parallel fear of and attraction to dark impulses, the paralyzing effects of moral ambiguity - were all near and dear to Hitchcock's psyche. Whatever it was, something in "Vertigo" spurred him to the heights of inventiveness. The film established many of the hallmarks audiences have come to expect in the suspense thriller. For starters, Hitchcock chose, in a move that was revolutionary for its time, to reveal the shocking dramatic twist involving Madeleine and Judy to the audience before the final act. His choice broke every known dramatic rule - yet it worked and set a precedent for what Hitchcock called "creating suspense not surprise." In today's most exciting features, the audience almost always knows who the bad guy is before the hero does. "Vertigo" also revealed that innovative use of visual effects could set the audience so much on edge they would feel the film, not just watch it. For many film fans, the shot of Scottie gazing into the depths below is among the most skillful and gripping ever seen. By zooming in and tracking out simultaneously, a move Hitchcock himself invented, he dares moviegoers to try to keep their equilibrium as they move back and forth between anticipating a fall and fearing it. Later, when Scottie finally kisses Judy, the couple appear to fade back into the stables where Scottie first kissed Madeleine. Here, Hitchcock put his actors on a turntable and performed a 360-degree tracking movement with the camera. The effect is to give the audience the sudden terror that even they don't quite have a grip on where reality stops and illusion begins. Today, the most popular action and suspense films continue to rely on tricky camera work almost as much as plot and performance to keep the audience on the edges of their seats. In addition to the superlative performances, "Vertigo" offered the world one of the most emotionally affecting musical scores ever written for the screen, a score that would reveal how music can get to the very innermost source of anxiety and emotion in suspense and psychological thrillers. |

|

Fort

Point, beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, Marine Drive, San Francisco Fort

Point, beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, Marine Drive, San FranciscoHitchcock left the score almost entirely in the hands of one of his favorite collaborators, Bernard Herrmann, who also wrote the score for "Citizen Kane" as well as most of Hitchcock's later films, including "North by Northwest" and "Psycho". (Later, Herrmann was to score Brian DePalma's "Obsession", widely regarded as the contemporary director's homage to "Vertigo".) In fact, Hitchcock so trusted Herrmann's musical instincts that in his meticulous sound notes he follows his description of the opening rooftop chase with the addendum "all of this will naturally depend upon what music Mr. Herrmann puts over the sequence." Despite working on his own, Herrmann seemed to know exactly where Hitchcock was going with the film. While Hitchcock's visuals revealed swirling graphics and spiraling patterns, Herrmann's score churns with the crescendoing strings of anxiety and the sustained chords of desire. The score features strains of Wagner, Mozart, and an Andalusian fandango, but the overwhelming result is a sweeping dreaminess and longing. When Scottie looks down with paralyzing terror as he hangs from the rooftop, his frenzied disorientation is echoed by the glissandos of harps. As he follows the bewitching Madeleine, Herrmann heightens the atmosphere of mystery and sadness with high-range violins and deep bass clarinets. Perhaps the score's most memorable moment comes when Scotty first embraces Judy and is transported in his head into the dead Madeleine's arms. Hitchcock decided to shoot the scene -- all five minutes of it -- without dialogue. "It will be just the camera and you," he told Herrmann. Herrmann came through with his insatiably passionate love theme, which harks back to Wagner's Liebestod from "Tristan und Isolde" as it soars from uncertainty to ecstasy. |

|

The Legacy of "Vertigo" |

|

Robert

Harris and James Katz at Fort Point, beneath the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Image

source: Robert Harris Robert

Harris and James Katz at Fort Point, beneath the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Image

source: Robert HarrisSince its release in 1958, "Vertigo" has become one of the most analyzed and discussed motion pictures ever. Perhaps this is because it seems to reveal so much about the hidden emotions, longings and psychology of the mysterious Alfred Hitchcock. Perhaps it is because so many elements came together--the alternately charming and charged performances of James Stewart, Kim Novak and Barbara Bel Geddes, the sly, suspenseful script, Robert Burks' groundbreaking cinematography, the haunting Bernard Herrmann score, the character-laden Edith Head costumes--so perfectly all at once. Or perhaps it is because Vertigo gives a visceral face to the wrenching human dilemma between desire and fear, illusion and reality, between taking a leap of faith and hurling into the abyss. Whatever way you approach it, "Vertigo" clearly has an indelible effect on all who view it. Today, it can be viewed as an extremely prescient movie, one that anticipates such contemporary themes as fear of commitment (not just fear of falling but fear of falling hopelessly in love) and such contemporary styles as psychedelia. As director Martin Scorsese summarizes: "This is an amazing movie...that sustains over the years because of its powerful truth and its unflinching themes." He adds: "Most American directors working today have been influenced by Hitchcock. There's no doubt. I mean I think you could see a lot of the sense of obsession that you see in Vertigo in the movies I've made." "Vertigo" takes its main character and the audience on a spiraling descent into the mysteries of attraction, commitment, identity and illusion. The film begins with an ominous roof-top chase scene that ends with police detective John "Scottie" Ferguson (JAMES STEWART) overcome with an intense dread of heights that leads to the death of a fellow officer. It turns out that Scottie suffers from severe acrophobia - a deep fear of falling which results in a stultifying vertigo, and must retire from the police department unless and until he finds an unlikely cure. With the help of an old girlfriend, the sensible Midge (BARBARA BEL GEDDES), Scottie attempts to return to a normal life. But his life takes another unusual turn when an old school acquaintance, Gavin Elster (TOM HELMORE), hires Scottie to take on a little freelance detective work. To Scottie's dismay, Elster asks him to shadow his wife Madeleine (KIM NOVAK), who he describes alternately as "being possessed by a spirit" and being a "suicidal neurotic." Scottie is wary but the minute he sees Madeleine he cannot resist the chase. Madeleine is not only lumaniscently beautiful but utterly mysterious. A patrician-looking blonde, she spends her days visiting ancient gravesites, staring at a portrait of a woman in an art museum, and gazing out the window of a small rented room in a rundown, historic hotel. She is there, but somehow not there, and Scottie finds himself yearning to sort out not only Madeleine but her macabre fascinations. The mystery and the lure only increase when Scottie saves Madeleine from an apparent attempt to throw herself into San Francisco Bay and begins a face-to-face relationship with her, keeping his other identity as her husband's hired detective a secret. In precious stolen moments, Scottie begins to fall madly in love. But as his fixation with Madeleine grows, so too does Madeleine's obsession with death. When Scottie takes her to visit an old mission she's described from a dream, Madeleine suddenly heads for the bell tower in a desperate act of suicidal panic. Once again, Scottie's fear of heights prevents him from coming to the rescue as Madeleine and his one chance at perfect love come crashing to a brutal end. But is it really over? Broken down and unable to go back to his ordinary life, Scottie continues to be haunted by the dead Madeleine. Then one day, he sees a woman walking down the street who looks just like Madeleine... and yet she can't be Madeleine, because Madeleine is dead. She is Judy Barton, a brunette department store salesgirl from Kansas with none of the alluring mystery and perfect poetry of the Madeleine for whom Scottie so irretrievably fell. But Judy also has her secrets - secrets which will once again turn Scottie's world into a dizzying battle between illusion and reality. |

|

• Go to Restoration of "Vertigo" |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |