Grant's Blow-Up Blog |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Grant Lobban, London, England | Date: 05.10.2007 |

"Doctor

Zhivago" was filmed in 35mm, but blown up to 70mm and given a very wide

release. MGM 1965. "Doctor

Zhivago" was filmed in 35mm, but blown up to 70mm and given a very wide

release. MGM 1965.Just in case there are any of you unfamiliar with the wonderful world of 70mm, a blow-up isn’t a print which ends its useful life by exploding in the projector. Sadly, most old 70mm copies, at least those printed before the early 1980s when more stable colour stocks were introduced, have a far less dramatic demise, they just fade away with everyone appearing in them ending up with a pink complexion. A blow-up is the term used to describe a print made by enlarging, or “blowing-up”, smaller formats, usually those on 35mm film, but 70mm prints have also been derived from 16mm and even 8mm originals. When they first appeared, I was rather sniffy about them and didn’t consider them to be “proper” 70mm, which like to original Todd-AO process, has to be photographed on 65mm negative with the same large image area. I must say now, before we start, that although it wasn’t love at first sight, I did come to appreciate blow-ups later. |

More

in 70mm reading: Who is Grant Lobban In German in70mm.com's list of films blown up to 70mm The Technirama Story In the Splendour of 70mm Come Back D-150 Todd-AO Distortion Correcting Printing Process 70mm Blow ups Internet link: |

The First Blow-up |

|

Unlike 70mm prints from 65mm negatives, which can be contact printed,

blow-ups are made using an optical printer. This is basically a

projector focusing its image into the gate of the camera. Apart from

changing the size, its optical system can include an anamorphic lens to

squeeze, or un-squeeze the image. Unlike 70mm prints from 65mm negatives, which can be contact printed,

blow-ups are made using an optical printer. This is basically a

projector focusing its image into the gate of the camera. Apart from

changing the size, its optical system can include an anamorphic lens to

squeeze, or un-squeeze the image.When did the first blow-ups hit the screen? To be strictly accurate, 70mm prints from Technicolor’s Technirama horizontal 8-perf. 35mm negatives should top the list. The height of its negative already matched that of a 70mm frame, so only a 50% horizontal enlargement was needed to restore the system’s squeezed image, as photographed by the camera’s x1.5 anamorphic lens, to produce the 70mm copy. Technirama began in 1956 with “The Monte Carlo Story”. The first British film in the process was the now largely forgotten Ealing Comedy "Davey” in 1957, but for me the first was "The Wikings". I was attracted by a fab poster featuring Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis comin’ at ya waving swords intent on, at least, pillaging. Whatever was going to happen could all be seen in “Horizon Spanning Technirama”. I learned later the film could only be seen in 35mm as the lack of 70mm projectors meant a wait until a year or so later in 1959 for the 70mm print option to be launched as the even more impressive Super Technirama 70. The first given the 70mm treatment were Disney’s animated feature “Sleeping Beauty” and the biblical epic “Solomon and Sheba”. These, along with other early 70mm showings, like “Barabas”, which were advertised as being in the “new” process didn’t add the magic “70” to the Technirama screen credit. |

|

Technirama

camera during filming of "El Cid" Technirama

camera during filming of "El Cid"Technirama was particularly popular in Europe as an alternative to 65mm. As it still used 35mm, it was easier to have processed and if necessary Technicolor could provide a mobile printer installed in a caravan (trailer) to help a local laboratory produce normal 35mm rushes from the large-area 8-perf camera negative. There were to be over 50 Technirama films before dying with “Custer of the West” in 1967. Not all were released using 70mm prints, but the system was to become one of my favourites widescreen processes. Being an epic fan, highlights included “Spartacus” and “El Cid”, one of producer Samuel Bronston’s blockbusters, most of which he chose to shoot in Technirama. One of his best, "El Cid"’s superb 70mm images included Sophia Loren. I have always “admired” her after, at an impressionable age, I saw her emerge all wet from the sea in “Boy on a Dolphin”. I had only gone to see the film because it was in CinemaScope, but I forgot the shape of the screen for a while until I learned you could love both of the shapely attractions at the same time. As far as I know, this particular film was never shown in 70mm, so my happy memories have distracted me from the subject of blow-ups. Although 70mm prints from Technirama negatives are technically in this category, I always considered them to be as good as “real” 70mm from 65mm. At a time when only a relatively few 70mm were made, they could be printed directly from the camera original, which had been specially processed with a contrast more suited to optical printing, resulting in even more beautiful prints. |

|

The True Blow-up |

|

What would generally be described as a blow-up is the 70mm prints form

conventional 4-perf. anamorphic (CinemaScope-type) negatives, joined

later by enlarging various image areas on normal 35mm “flat”

non-anamorphic originals. What would generally be described as a blow-up is the 70mm prints form

conventional 4-perf. anamorphic (CinemaScope-type) negatives, joined

later by enlarging various image areas on normal 35mm “flat”

non-anamorphic originals.Apart from the first Todd-AO film “Oklahoma”, which was simultaneously photographed in CinemaScope, the 35mm general release copies of 65mm shot films are made by reducing and squeezing the larger negative area down to produce an anamorphic print, which is compatible to CinemaScope, but with the potentially higher quality gained by the reduction process. (Like 35mm reduction prints from large-area VistaVision and Technirama negatives). By 1963, with ever improving film stocks, this optical conversation was reversed to enlarge an un-squeeze anamorphic negatives, now increasingly 35mm Panavision, up to a 70mm print. Despite the smaller negative area, the prints were judged to be more than satisfactory and helped to increase the supply of product for the rapidly growing number of 70mm installations. According to the much appreciated work of the 70mm list makers, the first blow-up shown in London was “Taras Bulba”. I missed spotting this one, so my first was “The Cardinal”. As I was still reeling from the 65mm visual splendour of “Cleopatra”, the screen image of the blow-up looked to me like very good CinemaScope projection. Although with a less smooth and noticeably more grainy image, compared to true 70mm, I must admit it was much brighter and steadier, and without the often magnified horizontal weave, I had begun to notice while watching some CinemaScope-type 35mm presentations. The film itself was a rather long Otto Preminger drama about the behind-the-scenes politics at the Vatican and didn’t have any battles in it, so it wasn’t quite my cup of tea. I suppose knowing what the first blow-up was, is important for us 70mm historians, but I’m not sure if anyone has come up with the definitive answer yet. I do have frames from one of the contenders “Bye Bye Birdie” dated 1963 (like antique silver, Eastman film stocks have “hidden” date codes) but I never saw this one in 70mm either. Blow-ups seemed to have arrived rather furtively, without the normal ballyhoo associated with the introduction of new widescreen methods. I enjoyed my second blow-up “Becket” much more. Again, its picture quality was overshadowed by another of my favourite epics “The Fall of the Roman Empire”. I also call it “The Fall of Samuel Bronston” as it was almost his last film, before he went out of business after the appropriately named “The Magnificent Showman”. “The Fall of the Roman Empire” wasn’t in his usual Technirama this time, but was hot in 65mm anamorphic (x1.25) Ultra Panavision. In a way, the copy I saw at the Astoria, Charing Cross Road, could be described as a 70mm blow-up. They showed a less wide normal 2.21:1 flat un-squeezed print which, during its printing, required a horizontal 25% enlargement, losing some of the original 2.7:1 image at the sides. However, it was composed to allow for this print option, so what was left still looked fantastic, including Sophia Loren!! |

|

The Brake Through |

|

“in

70mm” poster sticker. “in

70mm” poster sticker.Despite my own luke warm reception to blow-ups, one of them was going to make a big impression on both audiences and the industry. It was M.G.M.’s “Doctor Zhivago”. Although David Lean and Freddie Young had previously shot “Lawrence of Arabia” using 65mm Super Panavision 70 (same as Todd-AO), this time it was only ordinary 35mm anamorphic Panavision. However, it was promoted as a full scale 70mm production and accepted as such by most moviegoers who probably wouldn’t appreciate the difference even if we more passionate 70mm fans explained it to them. Producers too realised that they could give their films a 70mm road show presentation, without the added cost of shooting in a 65mm format. I must have been so put out, I wrote to M.G.M. to complain that the fact it was only a blow-up wasn’t made clear in the advertising. As I now worked at Ealing Studies as a BBC Film Department projectionist, the headed note paper I requisitioned for the purpose helped it from ending up in the crank letter bin. In the meantime, I had fun peeling off the “in 70mm” stickers from the poster, while waiting for my train home. Some weeks later, I was rather humbled by a reply forwarded from Metrocolor Labs in Culver City. They explained that their aim was always to present audiences with the best possible image. Even if originally shot on 35mm films, a printed up 70mm version, even when shown on a larger screen, is subject to less magnification, resulting in a brighter and steadier picture. The negative, sometimes the original, is enlarged and un-squeezed using a high quality printer lens (Micro-Panatar) compared to the possibly less than perfect projector anamorphic attachment used when showing a 35mm scope print, always now made from a duplicate negative. Not forgetting, of course, the other great benefit of 70mm was its multi-channel magnetic sound at a time when most 35mm prints only had mono optical tracks. This added attraction made musicals like “Funny Girl”, “Camelot”, “Sweet Charity” and “Paint your Wagon” ideal selections for a blow-up. Although not being a great musical fan, seeing and hearing the “who will buy” set-piece number in “Oliver”, helped me to begin to appreciate the advantages of blow-ups. I’m sure I had nothing to do with it, but the posters and ads now more often stated that the film was just “Presented in 70mm”. This would save any “trade description” trouble in the future, although the term was also used for proper 65mm originated films too. How could you tell it was only a blow-up? Apart from its coarser image, I looked out for the tell-tale signs that it had been shot with an anamorphic lens. One of the clues can be spotted in the out-of-focus areas, where bright points of light turn into ellipses rather than circles (of confusion). Although 65mm Ultra Panavision and Technirama both use anamorphic lenses on their cameras, the lesser amount of compression makes this particular artefact far less noticeable. Perhaps much easier are the process names on the films actual credits. All the 70mm blow-ups retained the original 35mm process used, so simply “Filmed in Panavision” meant it was a blow-up. Sometimes, the advertising material used the description “Panavision 70”. When first introduced, Panavision’s 65mm clone of Todd-AO used this credit, e.g. “West Side Story”, but the prefix “Super” was soon added to differentiate it from the blow-ups and possibly not to be out-supered by Super Technirama! With the extra audience appeal, including now for me, of 70mm paying off at the box office, some ealier films produced in rival formats were converted for a 70mm reissue. These included "Seven Brides for Seven Brothers", "The Longest Day” and “The Bridge on the River Kwai” in the original CinemaScope, together with “War and Peace” and “The Ten Commandments” from VistaVison’s large area negatives. 70mm prints were also made from the short-lived CinemaScope-55 process, when “The King and I” returned on “Grandeur 70” reviving the name of Fox’s old 70mm system from the 1920s. In fact, the new 70mm prints were reductions, as the image area of the 55 mm 8-perf negative was greater than 65mm. This was also the case when the combined area of the triple Cinerama negatives was used to make the 70mm conversions of “How the West was Won” and “This is Cinerama”. |

|

A Controversial Blow-up |

|

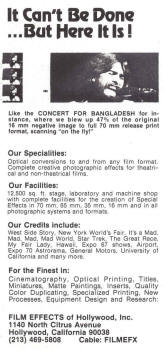

Film

Effect's advert for blowing “Concert for Bangladesh” up from 16mm to

70mm. Click image to see enlargement. Film

Effect's advert for blowing “Concert for Bangladesh” up from 16mm to

70mm. Click image to see enlargement.A more controversial blow-up was the often reissued “Gone with the Wind”, now to be seen and heard in the splendour of 70mm, Metrocolor and stereophonic sound. To change its original 1,37:1 academy format to the 70mm 2,2:1 aspect ration, a third of the image had to be discarded, with a special tilt-and-scan printer selecting the best composition for the chosen part of the image to be enlarged. With some trepidation, I went to see the results. I must say that putting myself in the shoes of a typical moviegoer, who didn’t remember seeing the original 1939 BC (before CinemaScope) 4:3 version, I was quite impressed. Considering the small area used from the Technicolor 3-strup negatives, the picture looked quite acceptable and what you lost in terms of image, you gained in sound, which was converted to stereo with added genuine stereo sound effects. It was worth seeing, as we are unlikely to have another revival in widescreen. When Ted Turner bought M.G.M., principally to acquire its film library, he restored “Gone with the Wind” back to its original format. It’s now in the hands of Sony Pictures, who are more interested in digital restorations. The 65mm blow-up inter-negative still exists, but it is unlikely that new 70mm prints will be struck. Any surviving 70mm copies would have by now, like other pre-low fade colour print stock films, gone too pink to be shown, except to dedicated 70mm enthusiasts, who’s brains have been trained to fill in the missing colours. Recently, I viewed a badly faded colour film with a nice, non-technical lady, who thought that this was the way it was supposed to look and was very restful compared to some more recent “gaudy” colour films (probably digital) she had seen. Perhaps with this in mind, we should give old faded 70mm prints another chance and promote them as being in easy-on-the-eyes “PinkVision”. However, the purists and critics who condemned the mistreatment of “Gone with the Wind” will be pleased to know that the 70mm born-again-in-widescreen prints have self-destructed and died of shame. After the “success” of "GWTW"’s makeover, M.G.M. gave another of its pre-widescreen films, Marlon Brando’s “Julius Caesar”, a 70mm outing. It was to become one of the few black and white 70mm prints. In this particular case, it was printed on colour stock giving it a tinted look. Other black and white blow-ups I can remember including the previously mentioned “The Longest Day” together with “In Harms Way” and “Is Paris Burning”, which burst into colour at the end. Columbia followed with 70mm updates of their 4:3 classics “The Jolson Story” and “The Great Caruso”. I hoped M.G.M. might try bringing back some of their other earlier epics like “Quo Vadis” and “Ivanhoe” in 70mm, but no luck. A good 70mm blow-up to see printed from many different formats was “That’s Entertainment”. A couple of pop festival films were blown-up to 70mm from 16mm, mostly multi-images, but sometimes from a single cropped frame. Examples were “Woodstock” and "Concert for Bangladesh". |

|

Major player: 70mm Blow-up |

|

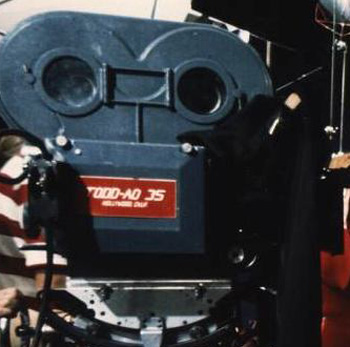

"Todd-AO

35" was 35mm - see logo on camera "Todd-AO

35" was 35mm - see logo on cameraIt was fortunate that my attitude to blow-ups was becoming more favourable as by the end of the 1960s they were beginning to outnumber true 65mm originated films, which weren’t always my kind of film. Gone were the days when I would go and see a film just because it was “in something” including 70mm. Apart from one or two like "2001: A Space Odyssey” and “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang”, which was fun, I was enjoying many of the blow-ups more. Like many Cinerama enthusiasts, I was less impressed by the single-lens version. My loyalty took another knock, when they showed their first blow-up “The Great Race” and I was strained once more as I tried to keep awake during “Song of Norway”. However, there was no going to sleep during the mayhem in the excellent blow-ups of “The Wild Bunch”, “Where Eagles Dare” and “Tora! Tora! Tora!”. Although not knowing it as the time blow-ups were going to keep 70mm alive as the era of the regular use of 65mm for theatrical motion pictures was effectively coming to an end with, for me, the somewhat disappointing “Ryan’s Daughter” in Super Panavision and “The Last Valley” in Todd-AO. Todd-AO kept in the widescreen business by providing anamorphic lenses for 35mm filming. Known as “Todd-AO 35”, most users credited them correctly but a few were naughty and left off the “35”. One offender was “Logan’s Run” shown in 70mm. The sight of “Filmed in Todd-AO” suggested that 65mm had returned but sadly it was only a blow-up. 65mm shooting occasionally tried to make a comeback with efforts like “Tron”, “Baraka”, “Far and Away” and “Hamlet”. Even Technirama reappeared, used for another Disney animated feature “The Black Cauldron”. |

|

Flat 35mm also Blown up |

|

Although 35mm anamorphic negatives were the most suitable for a blow-up

losing little of their 2.35:1 image when enlarged to 70mm’s 2.2:1,

spherical non-anamorphic 1.85:1 widescreen films were also beginning to

be blown up. Early examples were M.G.M.’s Robert Aldrich war films

“The Dirty Dozen” and “Too Late the Hero”. At first they were

enlarged to fill the full frame, or nearly so, of the 70mm print losing

some of the vertical composition. Another example was “Man of La

Mancha”, which I didn’t want to miss as it had Sophia Loren in it.

The extra cropping of the picture made me worry that I may be seeing

less of her attractive features than I had hoped for! (Sorry, I’ll try

not to mention her again). Soon, some directors and cinematographers,

fearing that their composition might be compromised, would only agree to

a blow-up if the original intended aspect ratio – usually 1.85:1 – was

kept. The optical printer’s magnification was reduced leaving unused

areas at the sides of the 70mm print. The first time I noticed this was

happening was Barbra Steisand’s “A Star is Born”. “E.T. - The Extra Terrestrial”

70mm frame from the Palladium in Malmø, Sweden. “E.T. - The Extra Terrestrial”

70mm frame from the Palladium in Malmø, Sweden.Although I call them 70mm “1.85:1” prints, the actual width of the picture varied from film to film. Some like “Cocoon” used more of the frame than others like “E.T. - The Extra Terrestrial” Although short-changed in terms of pictures, at least we had full-width sound. Unfortunately, some early showings even deprived us of this too. In an effort to give us the best presentation, the screen’s side masking was moved into giving a clean edge to the reduced with picture. In many theatres, this was made of heavy light absorbing serge material, which muffled the outer speakers, who had been positioned assuming the whole of the 70mm screen area would be filled. This was only a short-lived problem before screen manufactures provided acoustically transparent masking. I had enjoyed seeing Ridley Scott’s “Alien” in 70mm full-frame from 35mm anamorphic Panavision, but I was disappointed that the follow-up “Aliens” was only a masked-at-the-sides 70mm print from spherical 1.85:1. I saw this one after spotting a crowd outside the Odeon Marble Arch and sneaked in with them for the crew show. As it turned out, “Aliens” was the last film I experienced on the theatre’s giant deeply-curved D-150 screen. It was sad I didn’t see it completely filled for the last time before David Lean had it taken down and replaced with a flatter one before the allowed the theatre to show his restored “Lawrence of Arabia”. |

|

The

widest aspect ratio from "Napoleon" The

widest aspect ratio from "Napoleon"Although less often seen are the 70mm prints masked down vertically to retain the aspect ratios of originals wider than 70mm’s 2.2:1. A few blow-ups from anamorphic 35mm like “The Deer Hunter”, “Hook” and “Big Trouble in Little China” kept their 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Even more “letter box” was “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers”, which recreated the old 4-track magnetic sound 2.55:1 CinemaScope screen shape. Perhaps the 70mm version of Abel Gance’s “Napoleon”, apart from being made from the oldest original (1927), has the widest aspect ratio when showing the triple side-by-side triptych sequences, when only a narrow strip equal to 4:1 was placed across the 70mm frame. Again, it was more accurately a reduction. There were a few films which were a mixture of 35mm and 65mm. “Brainstorm” was largely 35mm 1.85:1 [1,54:1, ed], but the 70mm print opened out to its full 65mm glory for the all-in-the-mind-blowing virtual images. The film was directed by effects wizard Douglas Trumbull, who was able to make use of some of his Showscan footage (originally 65mm 60 f.p.s.). “Little Buddah” to was shot with both 35mm and 65mm cameras to change the visual texture of the image for different parts of of the story. |

|

Super 35 to 70mm |

|

|

An opportunity to fill the complete frame of a 70mm print from 35mm

spherical non-anamorphic negatives without increasing the magnification

or spoiling the original composition came about with the introduction of

what would become known as the Super 35 format. In the mid-1980s, Hugh Hudson wished to film his “Greystoke: Legend of Tarzan” in the 2.35:1 format. However, his DOP [director of photography], the late John Alcott, didn’t like using anamorphic lenses, so Technicolor suggested reviving the idea of photographing a normal spherical image across the fill width between the perforations on 35mm film, including the area usually left blank for the soundtrack during the contact printing of the release prints. This larger full-frame image is composed to allow a portion in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio to be enlarged and squeezed using an optical printer to produce a standard anamorphic print. As with “Greystoke”, a 70mm print can also be made using a little more height of the negative’s image. This method wasn’t new. Enlarging and squeezing up a section of a normal spherical image was the basis of Superscope in the 1950s and it was also used to convert old 4:3 footage for use in CinemaScope films. It had also proved useful earlier in 1982 when a plan to shoot the official record of the Football (soccer) World Cup in Technicolor’s old Techniscope process was thwarted by the lack of suitable numbers of 2-perf pull-down cameras. Joe Dunton proposed the same full-frame system. Although without the economy of 2-perf negative, the extracted image was somewhat larger. So became known as Super Techniscope. Other labs and camera rental companies came up with other names like Super Panavision 35 [Panavision Super 35, ed], System 35 and Super 35. The latter has stuck and has now been generally adopted together with recommendations for a common placement of the extracted area within the 4-perf full-width frame. Although with an image area only 2/3 of that on an anamorphic camera negative, the loss of quality is not too noticeable and this alternative 2.35:1 format has become popular with about 50% being shot this way. Among those printed up to 70mm, James Cameron’s “The Abyss”, “Terminator 2” and “Titanic” are good examples of the excellent results achieved. Others include “Howard’s End”, “Remains of the Day” and “Independence Day”, one of the last 70mm blow-ups. |

|

The Greatest number of Prints |

|

For many, the heyday period of 70mm shared that of the great epics and

big scale musicals of the 1950s and 1960s. However, it was the late

1970s and 1980s that saw the greatest number of prints manufactured.

Before this, the release pattern beginning with limited road show

engagements meant only a few 70mm copies were needed and had a long

life. For example according to an ad for the

DP70, a single print of “South

Pacific” ran for over two years at the Dominion in London. Only two

prints were made of “The Fall of the Roman Empire” for its

British 70mm release. These toured the country for many ears before

ending up in the National Film Archive and they have been revived many

times at the NFT. Fortunately, unlike many of its contemporaries, the

colour refused to fade until relatively recently. The number of prints

circulating began to rise starting with

“Star Wars” with about

30. As “blanket” releases became the norm in the 1980s. Blow-ups like

“The Empire Strikes Back” needed over 100 rising to 150 for

“Return of the Jedi” and the most over – 240 plus – for “Indiana

Jones and the Temple of Doom”. With increasing numbers, their

printing route now always included the making of a blow-up 65mm

duplicate negative for bulk printing on a high speed continuous contact

printer with any loss of picture quality being less noticeable due to

ever-improving duplicating film stocks. For many, the heyday period of 70mm shared that of the great epics and

big scale musicals of the 1950s and 1960s. However, it was the late

1970s and 1980s that saw the greatest number of prints manufactured.

Before this, the release pattern beginning with limited road show

engagements meant only a few 70mm copies were needed and had a long

life. For example according to an ad for the

DP70, a single print of “South

Pacific” ran for over two years at the Dominion in London. Only two

prints were made of “The Fall of the Roman Empire” for its

British 70mm release. These toured the country for many ears before

ending up in the National Film Archive and they have been revived many

times at the NFT. Fortunately, unlike many of its contemporaries, the

colour refused to fade until relatively recently. The number of prints

circulating began to rise starting with

“Star Wars” with about

30. As “blanket” releases became the norm in the 1980s. Blow-ups like

“The Empire Strikes Back” needed over 100 rising to 150 for

“Return of the Jedi” and the most over – 240 plus – for “Indiana

Jones and the Temple of Doom”. With increasing numbers, their

printing route now always included the making of a blow-up 65mm

duplicate negative for bulk printing on a high speed continuous contact

printer with any loss of picture quality being less noticeable due to

ever-improving duplicating film stocks.However, producing a 70mm print was still quite a task with longer delivery times. After processing, each print had to be striped and individually recorded with its magnetic sound. This was to remain the cinema’s premiere sound format even after Dolby’s stereo optical tracks brought higher quality multi-channel sound to 35mm. 4-track magnetic sound on 35mm remained in limited use but was never universally accepted by exhibitors so only mono optical sound could be heard in most theatres. Dolby also had an impact on 70mm’s 6-track system. Their noise reduction process was applied and the tracks reconfigured. The original five screen channels were reduced to three with the higher frequencies on the freed up two used to create directional surrounds and the lower used to add low frequency sub-bass effects/baby boom), which became fashionable after the success of “Sensurround”. This was first “felt” along with another successful blow-up “Earthquake” with the 70mm print having an additional control signal to trigger the earthquake rumble generator. (Prints were also available with the low frequencies included within the film’s normal soundtrack). Dolby’s now widely adopted stereo optical sound continued to close the quality gap between 35mm and 70mm sound and by the early 1990s, caught up with the coming of the various digital systems. The first of these CDS (Cinema Digital Sound) included a 70mm version. Although supported by Disney, it failed because it replaced the existing analogue tracks on both 35mm and 70mm, so it would require both types (duel inventory) to be produced. The ultimately successful Dolby, SDDS and DTS digital systems all found their own space on the same 35mm print without eliminating the existing analogue track. |

|

Decline of 70mm Presentations |

|

70mm releases declined rapidly into the 1990s and received what looked

like the fatal blow when the magnetic striping process was declared a

threat to the planet and effectively banded. Once on the print there is

no danger, but the stripes are applied in the form of a paste and this

“magnetic liquor” contains solvents and other eco-unfriendly chemicals.

I knew something was up when at the other end of the gauge scale, Kodak

withdrew their pre-striped stock I used in my direct recording Super-8

camera. The last 70mm prints striped by Technicolor in London were of

Kenneth Branagh’s “Hamlet”. I think the few labs still offering a

striping service were glad to see it go. In this digital age, it was a

relatively low-tech messy business. It sometimes went awry and has to be

washed off to have another try. Once successfully applied, the stripes

had to be recorded and checked with any dropouts meaning that the faulty

channel had to be rerecorded. All this increased the delivery time and

added to the high cost of a 70mm print up to three quarters of which was

just adding the sound. 70mm releases declined rapidly into the 1990s and received what looked

like the fatal blow when the magnetic striping process was declared a

threat to the planet and effectively banded. Once on the print there is

no danger, but the stripes are applied in the form of a paste and this

“magnetic liquor” contains solvents and other eco-unfriendly chemicals.

I knew something was up when at the other end of the gauge scale, Kodak

withdrew their pre-striped stock I used in my direct recording Super-8

camera. The last 70mm prints striped by Technicolor in London were of

Kenneth Branagh’s “Hamlet”. I think the few labs still offering a

striping service were glad to see it go. In this digital age, it was a

relatively low-tech messy business. It sometimes went awry and has to be

washed off to have another try. Once successfully applied, the stripes

had to be recorded and checked with any dropouts meaning that the faulty

channel had to be rerecorded. All this increased the delivery time and

added to the high cost of a 70mm print up to three quarters of which was

just adding the sound.All was not lost with help arriving in the form of the DTS digital system. This is the one which only has a control track on the print with the sound itself being on a separate CD. Apart from a few special premiere showings using an interlocked Dolby track, the last few 70mm releases and newly printed revivals have had an optically read code track printed just inside the left hand row of perforations and can if necessary use the same CD-ROM as the equivalent 35mm copy. Like many fellow 70mm fans, I can name practically all the “proper” 65mm shot theatrical films but it was difficult to keep up with all the 400 plus blow-ups. It’s all a matter of taste but looking at the lists some chosen, it seemed like a waste of 70mm. For me, you could forget “Howard the Duck”, but I thought other not on the list like “Speed” with its many POV shots from its speeding bus would have looked good in 70mm on a big curved screen. Blow-ups did enhance many big scale action movies among my favourites being “Die Hard”, “Predator” and “Terminator 2”. Of the more gentle 70mm presentations, I enjoyed ending up a little sad at the end of “Remains of the Day” not only about the future of 70mm. I was sometimes disappointed that films planned to be shown in 70mm weren’t. One of these was “The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes”. It was originally to be much longer, complete with an intermission and road show 70mm engagements. Even the sets at Pinewood were built with greater detail anticipating the bigger screens. Unfortunately, with 70mm not helping box office failures like “STAR!” and “Doctor Doolittle”, the distributors took fright and the film was trimmed by over an hour and no 70mm. More recent, what would seem to be ideal candidates for a blow-up like “Gladiator” were just too late and missed the 70mm boat. |

|

Some 70mm Anecdotes |

|

I’m sure most of you reading my piece have learned little new but to

end, here are a couple of blot-up related anecdotes, the first complete

with a namedropping warning. I’m sure most of you reading my piece have learned little new but to

end, here are a couple of blot-up related anecdotes, the first complete

with a namedropping warning.During my time as a projectionist at the BBC, Sir Richard Attenborough came in to prepare an interview helping to promote his directorial effort “A Bridge too Far”. He showed a couple of reels for the benefit of the programme’s presenter. During a chat afterwards, I said I was going to catch up with the rest of the films up in the West End. I also said that I had heard that it was in 70mm but this wasn’t being made much of in the advertising. He said the film had only been blown-up to avoid the British Quota so it could have a longer run at the Odeon Marble Arch. At the time – in 1977 – the quota was still in force trying to protect the British film industry from the dominance of Hollywood by requiring that, over a given period of time, all commercial cinemas (running standard 35mm film) must devote at least 15% of their screen time to British films. However, “substandard” 16mm, non-standard Cinerama and above-standard 70mm were exempt. (As was the below-standard 34mm ploy adopted for “Around the World in Eighty Days”). Although the film seemed fairly British to me, it didn’t qualify under the strict terms of the act as its budget did not include sufficient British labour costs. Before the quota ended in 1983, as well as helping British technicians to find work, the rest of us may have been able to see more 70mm. Apparently, in some more regulated countries like in South America you were allowed to charge higher prices when showing 70mm. I did hear that, like some one-off special premiere prints, which were blown-up and recorded late in the day, they sometimes only had mono or rudimentary (music only) stereo sound. This was confirmed when producer Euan Lloyd, speaking at this years’ Widescreen Weekend at Bradford, said it was his decision to have a 70mm print made for the premiere of his “Shalako”, but it was not widely seen afterwards. (Also missed by the list makers). Back to Sir Richard, I don’t think he was always impressed by 70mm. On stage at the Odeon Leicester Square, introducing the premiere of his later “A Chorus Line”, he announced that although the film was being presented in 70mm, the quality may fall short of expectations as it was “only a blow-up from 35mm” (Super 35). |

|

|

My favourite blow-up story was told to me by a friend and colleague at

the BBC. On a foreign holiday, he met a nice girl who said she sometimes

worked as a projectionist. She had a boyfriend back home who had an

ambition to open the most luxurious and highest quality pornographic

film theatre in Germany. To this end and with help from his rich

parents, he ordered 70mm projectors from Philips. Unfortunately, he soon

found out that his chosen genre wasn’t well represented in 70mm. With

the prospect of the projectors being returned, Philips suggested he

tried an enlarged print from 35mm or even 16mm. A suitable subject was

sent to Technicolor in London who happily took the money for a quick

blow-up job. She said the visuals, their picture quality at least, were

terrible, but the sound was fantastic! Before long, due to lack of 70mm

porn, the cinema went mainstream with the showing of “Lawrence of

Arabia”. My friend said she was very plausible and the details too

specific to be made up, but we were never able to confirm them. A good

research project for a local German enthusiast (for 70mm of course). |

|

Supply of 70mm Drying up |

|

|

The last blow-up with a significant number of 70mm prints was

“Titanic” before going out with the big bangs in the special prints

of “Independence Day” and “Amageddon”. We may have come to

the end of 70mm for current releases and with the supply of product

drying up, remaining theatres may not hang on the their 70mm facilities.

With the emphasis now directed to digital cinema, 35mm prints are in

increasing danger too. Looking at the bright side, I’m still able to enjoy the 70mm revivals like “Vertigo” and the superb new prints of “Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines” and “Cleopatra”. It could be argued that there is less point in making new prints of even a classic blow-up as it was never really a true 70mm film in the first place. Fortunately, big screen 70mm film festivals like the Widescreen Weekend (Bradford) and Todd-AO Festival (Karlsruhe) still come up with great blow-ups from the past and if they weren’t included in the programme along with proper 65/70mm films, we would all have to go home early. |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|